War in the Pacific

War in the Pacific National Historic Park

Historic Resource Study

|

|

B. ASAN BEACH UNIT, ASAN INLAND UNIT AND FONTE PLATEAU UNIT

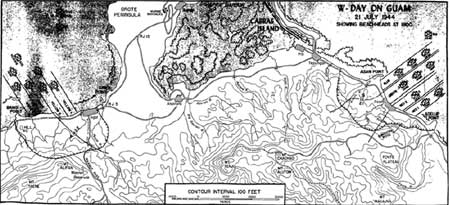

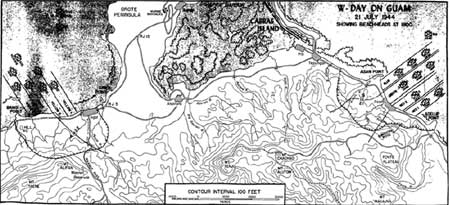

On W-Day, July 21, 1944, the lead elements of the 3d U.S. Marine

Division crossed a reef from 200 to 500 yards offshore and landed on

Asan Beach, which was defended by the Japanese 320th Independent

Infantry Battalion and naval troops manning the coastal defense guns.

The 1.3-mile-long landing area was flanked by two rocky points, "the

devil's horns," extending into the lagoon. On the east (left) was Adelup

Point. West and to the rear of Adelup was steep Chorrito Cliff which

extended almost to the water's edge. Farther west, the cliff gave way to

low level land covered with rice paddies. Asan River joined the sea in

this area and the small village of Asan lay scattered among palm trees

on the beach. At the western end, rocky Asan Point bordered the beach.

From east to west, two battalions of the 3d U.S. Marines Regiment landed

on Beach Red 1; one battalion of the 3d U.S. Marines landed on Beach Red

2; three battalions of the 21st U.S. Marines came ashore on Beach Green,

in the middle; and three battalions of the 9th U.S. Marines landed on

Beach Blue adjacent to Asan Point. The Japanese held their fire until

the landing vehicles were close to shore, the 3d U.S. Marines

particularly receiving heavy fire from Adelup Point and Chorrito Cliff

on their left flank.

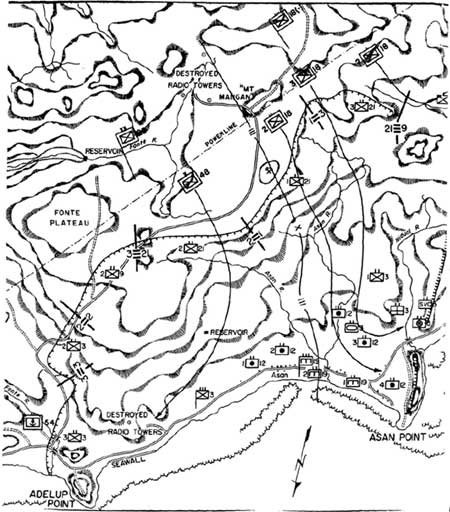

By noon the 3d U.S. Marines had reached the top of steep Chorrito

Cliff and in the afternoon overcame the enemy on Adelup Point. Inland

from Chorrito Cliff, the terrain becomes a ruggedly hilly area cut by

deep ravines and covered with man-high sword grass and other jungle

vegetation. The marines named one 400-foot-high rocky outcropping

Bundschu Ridge for Capt. Geary R. Bundschu, who was assigned to take

this ridge. Here, the Japanese held off the marines throughout the day

and inflicted heavy casualties, including the life of Captain

Bundschu.

In the center of the landing beach, the 21st U.S. Marines advanced up

the Asan River valley against only moderate resistance until they

reached a series of ridges from which Japanese fire forced the marines

to dig in for the night.

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

To the west, right, the 9th U.S. Marines made the day's greatest

advance, but suffered casualties from caves on Asan Point. It crossed

the rice paddies swiftly and reached the inland ridge. Part of the

regiment swung to the southwest, crossed a bridge near the mouth of

Matgue (then called Nidual) River, and moved on to a point 400 yards

short of Taguag River near Piti. When these marines crossed the Matgue

River, fire from Japanese positions on the west side of Asan Point fell

on them. By nightfall, however, all enemy opposition on the point had

been silenced. Through the night, Japanese reinforcements plugged gaps

in their lines on the ridges above Asan. And through the night, small

groups of Japanese counterattacked along the 3d Marine Division's front,

the most serious blow being against the 3d U.S. Marines in the Chorrito

Cliff area.

On July 22, the 3d U.S. Marines renewed their attack on Bundschu

Ridge. Despite repeated attempts against the natural stronghold, the

marines gained no ground and continued to suffer heavy casualties. The

21st U.S. Marines to the right attempted to make contact with the 3d,

but "the nightmare of twisting ravines, jumbled rocks, and steep cliffs

that hid beneath the dense vegetation" precluded the effort. [2] That night, the Japanese counterattacked again,

and again suffered severely. Unknown to the marines, the Japanese

withdrew from Bundschu Ridge before dawn.

To the right, the 9th U.S. Marines continued their advance on July

22, entering the Piti area and taking the old navy yard and a Japanese

three-gun coastal battery.

On July 23, after occupying Bundschu Ridge, the 3d U.S. Marines

pushed their attack toward the high ground west of lower Fonte River.

The 21st U.S. Marines in the center spent the day improving their

positions, establishing outposts, and beating off Japanese patrols. Not

until the next day, July 24, was the gap between the 3d and 21st closed.

On the night of July 25-26, the Japanese launched their last major

counterattack against the 3d Marine Division. One of the most bitter

struggles involved the 9th U.S. Marines on the forward slopes of the

Fonte Plateau, the high ground toward which the marines had been

struggling since W-Day. Along the entire front, Japanese infiltrators

made their way down to the beach, striking at various targets including

the division hospital near Asan Point. The counterattack was in vain,

however, for the Japanese lost 3,200 men that night. On July 27, the

Third Division launched an all-out attack on the Fonte area. By the 28th

all the Fonte area was in American hands except for a depression on the

plateau which was silenced on the 29th. General Takashima was dead,

having been hit by machine gun fire from an American tank. Japanese

forces began a general retreat toward northern Guam.

Following the battle for Guam, great changes occurred in the

Asan-Fonte area. The rice paddies on the beach gave way to a motor pool

area and a cemetery for American dead. Seabees constructed a four-lane

highway, Marine Drive, along the shore, changing the face of the

Chorrito Cliff. Still later, the motor pool gave way to a naval

hospital. Asan Point was opened as a coral quarry, destroying remaining

fortifications and changing the point into low, level ground. The old

village of Asan was destroyed during the fighting, and a new town of the

same name was erected farther inland to the east. The high land of Fonte

was renamed Nimitz Hill and Admiral Nimitz moved his CINCPAC

headquarters there from Hawaii. In recent times, a large modern school

was constructed on Adelup Point and a flood-control project was

completed at the mouth of Asan River.

I. Asan Beach Unit

The Asan Beach Unit consists of 109 land acres and 445 acres of

water. It includes all of Asan Point, the landing beaches seaward of

Marine Drive, and the western side and tip of Adelup Point. (The

identifying numbers used below are those used by the National Park

Service up to now. A new numbering system, which will provide more

order, presently being developed by the area.)

|

|

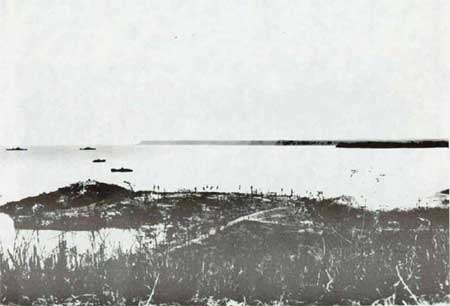

Adelup Point, 1944.

|

|

|

Asa Point from Adelup Point, Asan Beach, 1984.

|

|

|

Agana from Adelup Point, 1984.

|

Adelup Point

No. 28. Japanese Pillbox. On the west side of the point. Presently

owned by the Government of Guam, it consists of a single concrete wall,

5 feet in length, and containing a small embrasure. It lacks a roof. The

field of fire was toward Asan Point. Battle damage is limited, but rock

has fallen into the firing position. Japanese lire from the west side of

Adelup Point hit the 3d U.S. Marines on Beaches Red 1 and 2 on W-Day.

The point was captured by the end of the day.

No 29. Japanese pillbox. On the east side of Adelup Point. It is

outside the boundaries of the national park. Built into the limestone

cliff, this pillbox has two gun embrasures, one of which is now sealed

with concrete. The rear entrance, from the top of the dill, is filled

in. Located on the east side of the point, this pillbox played no direct

rote in the W-Day landings. One may be assured, however, that its

occupants partook in the defense of Adelup Point when U.S. Marines

stormed it that afternoon. While the National Park Service has no

responsibilities concerning the pillbox it is recommended it be

identified in any interpretive literature that may be developed for

Adelup Point.

|

|

No. 29. Japanese pillbox, Adelup Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 29. Japanese pillbox, Adelup Point, 1984.

|

No. 30. Japanese pillbox. On the east side of Adelup Point, outside

the boundaries of the National Park. This fortification has been

described as a "dual" pillbox, having two rooms (one large and one quite

small), each with a gun embrasure. The cliff parallel to the westernmost

embrasure has been chiseled out to increase the field of fire. A

concrete observation port remains on top. As with No. 29, the pillbox

played no direct role in the W-Day landings. It is recommended that it,

too, be identified on any trail guides for Adelup Point. This is an

excellent example of an essentially undamaged and completed Japanese

pillbox.

|

|

No. 30. Japanese pillbox, Adelup Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 30. Japanese pillbox, Adelup Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 30. Japanese pillbox, Adelup Point.

|

|

|

No. 30. Japanese pillbox, Adelup Point.

|

No. 31. Natural cave. On the north tip of Adelup Point, within the

park boundaries. This small cave may or may not have been defended.

Pieces of concrete have been found within. It measures 6 feet in depth

and 5.5 feet in width.

|

|

No. 31. Cave, Adelup Point, 1984.

|

No. 32. Cave and foxhole. These are on the west side of Adelup Point,

within the park boundaries. The Government of Guam is the present owner.

The natural cave, measuring about 5.5 feet in width and 10.8 feet in

depth, could well have served as a weapon emplacement. On top of the

cliff above the cave is a depression in the earth 3 feet in width, 6 in

length, and 3 feet in depth, that probably was a machine gun

emplacement. Both machine gun and mortar fire from Adelup Point fell on

Beaches Red 1 and 2.

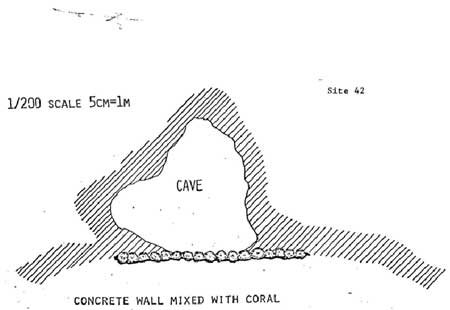

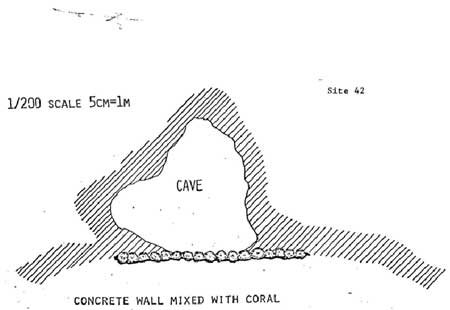

No. 42. Cave. It, too, is on the west side of Adelup and within the

park boundaries. The Government of Guam is the present owner. This

natural cave is faced with a coral rock and concrete wall. The cave

measures 6.5 feet in width and 8 feet in depth. Its field of fire

covered Beaches Red 1 and 2.

|

|

No. 42. Cave, Adelup Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 42. Cave, Adelup Point.

|

No. 41. House foundation. This large, concrete foundation on the

highest part of Adelup Point marks the site of the pre-war Kroll home.

It is believed that the Japanese dug tunnels into the landward sde of

the foundation for storage; there is a definite evidence that this wall

was breached and later resealed. Also, a photograph taken on July 23,

1944, shows at least one opening in the wall. A long concrete flight of

steps from the house to lower ground from before the war remains. These

steps are bordered with small, rock-walled flower terraces of an

uncertain date (after the battle an American officers' club was

established on the house foundation). It provides an excellent platform

for viewing Asan Point to the west and Aqana to the east and is an

outstanding location for on-site interpretation,

|

|

No. 41. Kroll House, Adelup Point.

|

|

|

No. 41. Kroll house foundation, Adelup Point, 1944.

|

Asan Landing Beaches

No. 33. Seawall. This rock and concrete seawall is within the park

boundaries and is owned by the Government of Guam. It is near the base

of a small knoll on the beach, 2,000 feet west of Adelup Point. It is

part of a longer seawall that existed in 1944. The rocky Knoll is

separated from Chorrito Cliff by Marine Drive. The original seawall

protected the federal road from Agana to Piti that ran along the base of

Chorrito Cliff in this area. The existing wall is 75 feet in length and

40 inches in height. (The original wall was about 440 feet in length.)

The writer suspects that the wall existed before 1941, when the U.S.

government funded maintenance of the road. The wall is subject to

potential storm damage. It is recommended that the seawall not be

interpreted onsite. Parking on MarinebDrive in this area is extremely

dangerous.

|

|

No. 33. Seawall, Asan Beach, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 33. Seawall, Asan Beach, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 33. Seawall, Asan.

|

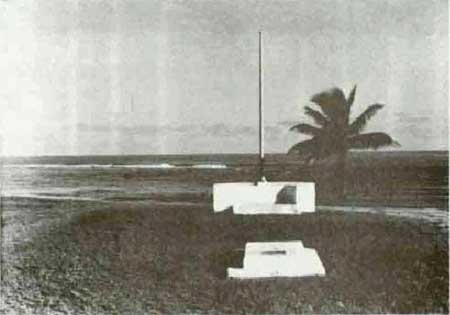

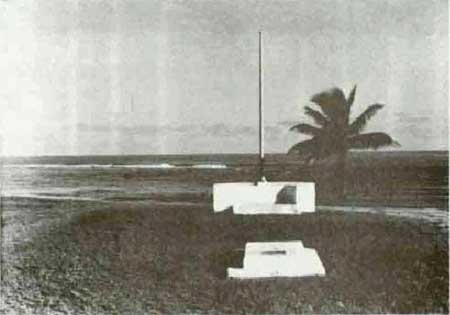

No number. Civilian Landing Memorial. It is near the beach in front

of the present town of Asan and east of the mouth of the Asan River. It

is a simple concrete wall with a flagstaff rising from its center. On

the wall in front of the flagstaff an artillery round is mounted

upright. Good views of the landing beach and the hills to the south are

found here. Guamanians gather there annually to commemorate the

liberation of their island.

No number. U.S. Landing Monument. It is near the water's edge on

Beach Green where the 21st U.S. Marines landed and where the old village

of Asan stood. The white, concrete monument is rectangular in shape; at

the top of the spire is a metal reproduction of the U.S. Marine Corps

insignia. Four metal plaques, one on each side, have texts that outline

the history of the battle, list the several commanders, and dedicate the

monument to all American dead. The monument was dedicated by Gen. Lemuel

C. Shepherd, Jr., Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1952-1955. In

1944, Brigadier General Shephard commanded the Agat landings on Guam.

The area around the monument has been pleasantly landscaped with palm

trees. The monument is in excellent condition, requiring only periodic

painting. (An identical monument has been erected on Wake island.)

|

|

Civilian Landing Monument, Asan Beach, 1984.

|

|

|

U.S. Landing Monument, Asan Beach, 1984.

|

No. 102. Japanese Pillbox. It is in the water just of the beach

approximately on the right flank of Beach Blue. It was severely damaged

in the 1944 invasion and is overturned. It is obviously not on its

original site and probably was placed there when the Americans cleared

the general area for logistical operations. In its ruined state, the

pillbox is a dramatic example of the destruction rained on Guam by

American firepower. Since it is not in situ, the pillbox could be

replaced on dry land to reduce the erosion by the sea. No restoration

should be attempted.

|

|

No. 102. Japanese pillbox ruins, Asan Beach, 1984.

|

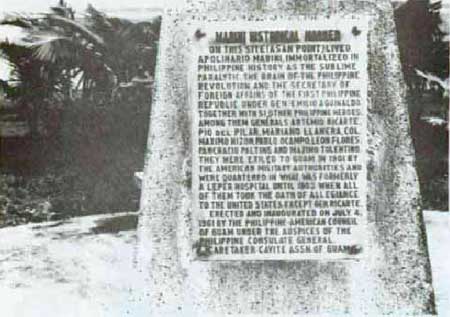

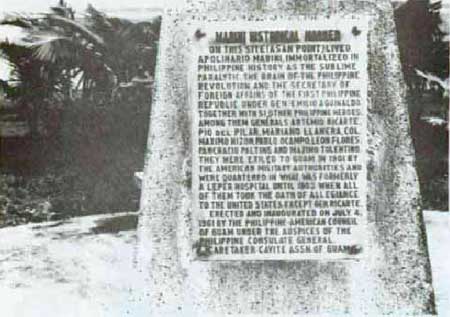

Nos. 45 and 52. Two Mabini Monuments. They are on the water's edge

approximately on the right flank of Beach Blue. The monuments are not

associated with World War II. They commemorate the place of exile of a

group of Filipino insurgents, including Apolinario Mabini, "the Brains

of the Revolution," who had refused to take an oath of allegiance and

criticized the American military government. They arrived at Asan in

1901. Most returned to the Philippines in 1902. Mabini himself returned

home in 1903, just before his death. The west monument, No. 45, is a

crushed coral pyramid having a legend inscribed in marble. It is

surrounded by the concrete benches. A chain (some sections missing)

encircles the whole. The monument was erected in 1961 by the

Philippine-American Council of Guam. The east monument, No. 52, is a

simple concrete slab with a metal plaque attached. Some corrosion has

occurred to the metal. This marker was erected in 1964 by the

Philippines Historical Committee.

|

|

Nos. 45 and 52. Two Mabini monuments, Asan Beach, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 45. Legend on Mabini monument, 1984.

|

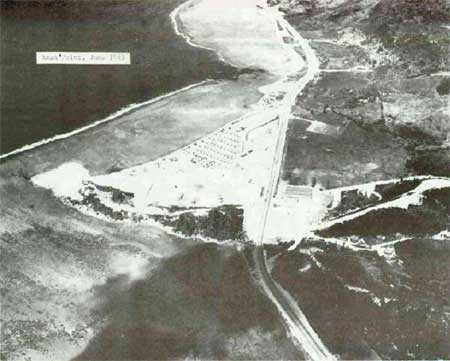

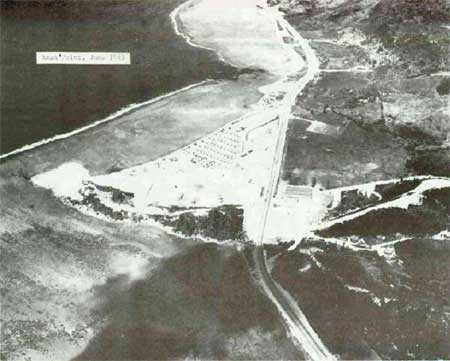

Asan Point

Asan Point as the other "devil's horn" flanking the American landing

beaches. After the battle, American forces opened a quarry on the tip of

the point and on the ridge behind, forever destroying any Japanese

fortifications located at these sites. On the east side of the ridge,

i.e., facing the American landings, only a Japanese tunnel remains. On

the ridge's west side, a complex of pillboxes remains. Some of these

played an important role when the 9th U.S. Marines crossed Matgue River

and pushed southwest toward Piti. Once the Marines passed Asan Point,

the Japanese here opened fire, forcing the Marines to turn around to

counter the attack. Asan Point was neutralized by the end of W-Day. The

fortifications on the west side are reached via a road/trail (that needs

a sign identifying it) beginning on the east side of the ridge and

descending the west side via recently installed steps. The trail on top

of the ridge continues south to the highest point directly overlooking

Marine Drive. This overlook provides an excellent view of the landing

beaches all the way east to Adelup Point and offers good possibilities

for on-site interpretation. The trail along the base of the west side of

Asan Point, from feature 54 to feature 69, has recently been partly

disrupted by rockfall caused by an earthquake. Plans are to redirect the

trail around the boulders and add earthquake history to the

interpretation of the area.

|

|

Asan Point and Asan village, July 31, 1944.

|

|

|

Asan Point, June 1943.

|

|

|

Asan Beach area from Asan Point, 1984.

|

No. 61. Japanese pillbox. Constructed of reinforced concrete, it is

on the west base of Asan Point. It has a gun embrasure and two rifle

firing ports. It was extensively damaged by a direct hit above the

embrasure and by a satchel charge on its roof. The pillbox cannot be

entered in its present condition. Although the damage should not be

repaired, the entranceway to the pillbox could be cleared.

|

|

No. 61. Japanese pillbox, Asan Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 61. Japanese pillbox, Asan Point.

|

|

|

No. 61. Japanese pillbox, Asan Point.

|

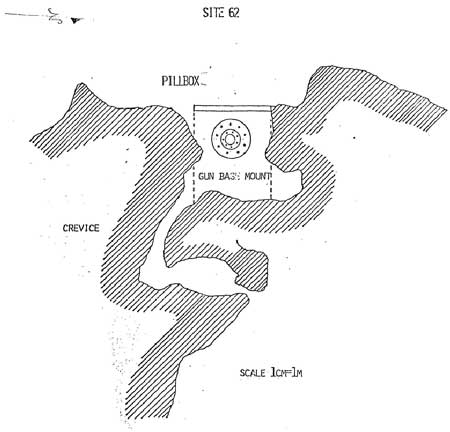

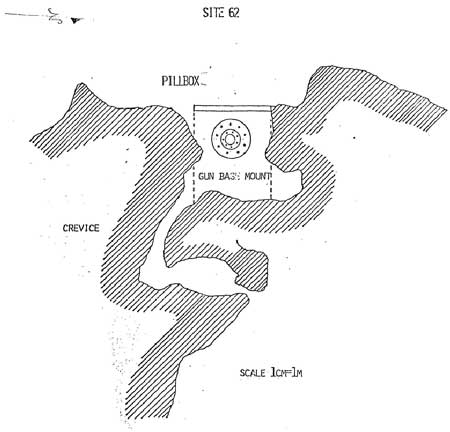

No. 62. Japanese pillbox (large caliber gun emplacement). Also

located on the west base of Asan Point. Here, the Japanese took

advantage of a large, winding crevice in the limestone cliff. A

reinforced-concrete was built against the cliff. A low

reinforced-concrete wall was added to the front of the opening. To the

rear, the crevice was used for ammunition storage. In areas where the

rock walls of the crevice were low, the Japanese built them up with rock

and concrete. A steel gun base remains. (Marines recorded finding three

20 cm. (8-inch), short barrel naval guns in this area.) The horiztonal

I-beams supporting the roof have rusted considerably and other iron work

is heavily corroded. Some spalling of the concrete ceiling has

occurred. Park maintenance has installed stout wooden planks as a

temporary support to the ceiling. This pillbox should receive early

attention from historical architects, addressing the issues of

preservation and visitor safety.

|

|

Asan Point, October 1944.

|

|

|

No. 62. Japanese gun emplacement, Asan Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 62. Japanese gun emplacement, Asan Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 62. Japanese gun emplacement, Asan Point.

|

|

|

No. 62. Japanese gun emplacement, Asan Point.

|

No. 63. Japanese wall. At the base of the west side of Asan Point,

two natural crevices, side by side, lead into the limestone cliff. In

front of these, the Japanese erected a coral rock and concrete wall for

the protection of the crevices which they used for storage or shelter.

Only a part of the wall remains which ranges in height from 20 inches to

3.5 feet. Vegetation tends to grow profusely on the wall, resulting in

the never-ending chore of removing it. Historic preservationists may

wish to examine this structure to determine a permanent cure for the

vegetation problem.

|

|

No. 63. Japanese rock and concrete wall, Asan Point, above crevices in

cliff behind wall, below.

|

|

|

No. 63. Japanese rock and concrete wall, Asan Point, above crevices in

cliff behind wall, below.

|

|

|

No. 63. Japanese rock and concrete wall, Asan Point.

|

No. 64. Japanese pillbox (large caliber gun emplacement). This

structure is also built into the base of the limestone cliff on the west

side of Asan Point. An entrance was constructed on the north side of the

structure and is concealed from view as one faces the large embrasure. A

low concrete wall forms the face and it does not meet the south side of

the emplacement, thus providing a second entrance. A steel gun base

remains installed in the floor, suggesting this structure housed another

of the 20cm coastal guns. To the rear are two caves, one of which

extends upward to the top of Asan Point. Near the tunnel's exit on top

are the remains of the foundation of a small rectangular structure whose

function is unknown. Like No. 62, the iron I-beams supporting the

ceiling of the emplacement have greatly rusted. Also, one or the caves

is filled with rock rubble. Historical architects should study this site

for its preservation and safety needs.

No. 67. Cave. This natural cave is just north of feature No. 64, at

the base of the west side of Asan Point It is a small cave measuring 4

feet in depth and 6.7 feet in width. The Japanese protected its entrance

with a concrete wall, a portion of which remains on either side of the

entrance. The cave is sufficiently large for a machine gun

emplacement.

|

|

No. 64. Japanese gun emplacement, Asan Point, October 1944.

|

|

|

No. 64. Japanese gun emplacement, Asan Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 64. Japanese gun emplacement, Asan Point.

|

No. 106. Japanese tunnel. This Chamorro-built (forced labor) tunnel

is the sole surviving Japanese defense structure on the east side of

Asan Point. The large cave is easily accessible to visitors. Like all

tunnels, rock rubble gathers on the floor and as a matter of visitor

safety must be regularly checked. Interpretation, on- or off-site,

should be developed for this tunnel and all of Asan Point.

|

|

No. 106. Japanese cave, Asan Point, 1944.

|

|

|

No. 106. Japanese tunnel, Asan Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 106. Japanese tunnel, Asan Point, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 106. Japanese tunnel, Asan Point.

|

II. Asan Inland Unit (593 acres)

Chorrito Cliff and Bundschu Ridge (Sabanan Adelup). As it was in

1944, this area is extremely difficult to explore. It remains in a

natural state, with little evidence of the fierce fighting of 1944.

Tall, thick, sharp sword grass, vines, tangantangan thickets, steep

ravines, and rocky outcroppings, combined with heat and humidity, make

travel exceedingly difficult and exhausting.

|

|

Chorrito Cliff from Adelup Point, Asan, October 1944.

|

|

|

Stalemate on Bundschu Ridge, Asan, July 22, 1944.

|

|

|

Japanese 150mm gun on Chorrito Cliff, Asan Point in distance, October

1944.

|

|

|

Asan Point from Bundschu Ridge, 1984.

|

|

|

Looking over Chorrito Cliff area to the sea, 1984.

|

No. 57. Natural caves and crevices. Presently privately owned but

within the park boundaries. These are on a ridge above Bundschu Ridge in

an area where heavy fighting occurred. Several small caves and crevices

provided protection to Japanese soldiers. Unexploded shells and Japanese

gas masks and mess kits were found here. Access to the area is

difficult.

No. 59. Japanese observation post. This concrete post or artillery

fire control station was not completed. Its roof is missing. Most of the

structure is underground, which is typical of such posts. This structure

may have been a fire control center for three 150mm guns emplaced lower

down, on Chorrito Cliff.

No. 85. Japanese pillbox. This reinforced-concrete pillbox on

Chorrito Cliff is the only substantial structure in the Asan Inland

area. It has one embrasure and most likely served as an automatic

weapons emplacement, wreaking havoc on U.S. Marines attempting to scale

the cliff. Some slight shell damage occurred to the exterior of the

pillbox. A great view of the Asan landing beaches is to be had from

this site. It is recommended that if an interpretive trail is developed

on Sabanan Adelup, it take in this pillbox, which is not easy of access.

It is also recommended that an archeological examination be made of the

area, with the view to making the interior of the pillbox

accessible.

|

|

No. 85. Japanese pillbox. Asan Island, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 85. Japanese pillbox. Asan Island.

|

No. 85A. U.S. dump. Here, high on the Sabana Adelup is a dump

established by the American forces. Among the artifacts are the rusting

scraps of American jeeps, coke bottles, and navy china. The site is

heavily overgrown with tangantangan.

No. 98. Foxholes and shell craters. An unknown number of shell

craters and foxholes are scattered along the ridge. Vegetation is thick

in this area and other features may exist.

No. 100. Trench, gun emplacements, and caves. There is a well-defined

trench running along the forward slope of the ridge. American and

Japanese grenades were found here.

|

|

No. 100. Trench, Asan inland, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 100. Cave, Asan inland, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 100. Cave, Asan inland.

|

Matgue (Nidual) River Area

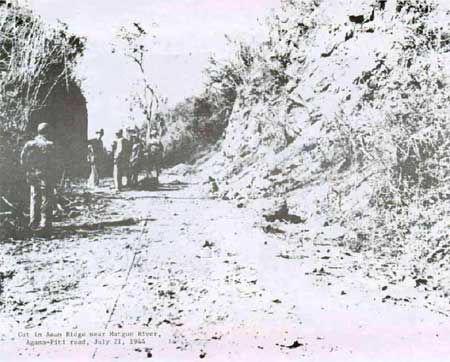

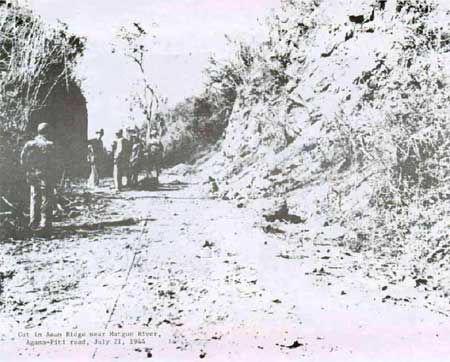

No. 86. Bridge. Concrete bridge over the Matgue River, near its

mouth. The bridge now serves a short, dirt road that runs up the west

side of the river. In 1944 a bridge existed in this area, serving the

Agana-Piti road. On W-Day, elements of the 9th U.S. Marines crossed the

bridge and came under fire from Japanese dug into the west side of the

Asan Point. Following the battle for Guam, U.S. forces established four

large petroleum storage tanks in the river valley. A service road joined

this storage area to the newly constructed Marine Drive, crossing the

river where the bridge now stands. The consensus appears to be that

today's bridge was built in this period. The writer disagrees, believing

the bridge to be a part of the pre-war route from Agana to the Piti Navy

Yard. A document, uncovered by Historian Charles Snell, that was

prepared by the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence prior to the American

invasion of Guam discussed the pre-war bridges and roads on Guam. In

part, this report states, "On the AGANA-PITI-SUMAY road, which is

maintained by the [U.S.] Federal Government, all bridges are two-way,

and of heavy reinforced concrete construction until the ATANTANAO River

is crossed." [3] The deck of the bridge

measures 32.5 feet in length and 19 feet in width. An iron pipe rail is

affixed to the north side. Thick vegetation prohibits a clear photo.

|

|

Cut in Asan Ridge near Matgue River, Agana-Piti road, July 21, 1944.

|

|

|

Matgue River bridge, Asan, 1984.

|

|

|

Matgue River bridge, Asan, 1984.

|

Nos. 88 and 89. Caves. Two man-made caves tunneled into the side of

the cliff along the west side of Matgue River. No. 88 is 10 feet in

depth and 4.3 feet in width, and No. 89 is 10 feet deep and 7 feet wide.

Both were suited as personnel shelters or for storage.

|

|

No. 88. Japanese cave, Matgue Valley, Asan, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 89. Japanese cave, Matgue Valley, 1984.

|

Nos. 90, 94, and 97. Caves. Man-made. No. 90 has two entrances and is

13.5 feet in depth. Ore of these entrances is blocked with rock rubble.

No. 94 consists of three small caves that have collapsed. No. 97 is a

large cave, 27 feet deep, suited as a personnel shelter.

No. 106(?). Gun emplacement. It is on the ridge west of Matgue River

and south of Asan Point. The principal feature is a gun emplacement,

cup-shaped, 8 feet in diameter and 2.5 feet in depth. A raised lip

surrounds it. Possibly an emplacement for a Japanese antiaircraft gun.

In the vicinity are several foxholes or shell craters. (No. 106 seems to

have been assigned to two sites.)

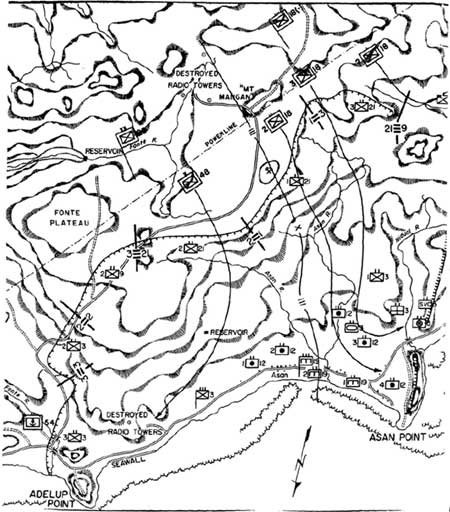

III. Fonte Unit (approximately 38 acres)

The Fonte area was that area captured by U.S. Marines July 27-29,

1944, including the Fonte Plateau as shown on the official maps. In

analyzing the combat narratives and reports, it is clear that the term

was used to include all the high land above Asan from the Plateau in the

east to Mt. Mangan, 1,500 yards to the west, i.e., the high, fairly

level area known as Nimitz Hill. At the rear of the plateau proper is a

concrete bunker having two concrete-arch entrances. This feature has

traditionally been called the command post of General Takeshima. The

plateau itself was captured by a battalion of the 9th U.S. Marines. The

21st U.S. Marines captured the high ground west of the plateau. This

report identifies the bunker as a major Japanese naval communications

center, not a command post. [4] Similar to the

communications center at Agana it was still under construction when U.S.

forces landed on Guam. Three radio towers were at the head of Fonte

River on the rear slope of Mt. Manqan.

The climax of the fighting for the Fonte area occurred on the morning

of July 29 when the 9th U.S. Marines wiped out the Japanese defenders in

a bowl-shaped depression on Fonte Plateau proper, "the Fonte Bowl,"

which was honeycombed with caves. The marines took the bowl without a

single casualty while killing from 35 to 50 Japanese. This action

completed the capture of the Fonte area. Although some writers have

concluded that the depression was General Takeshima's command post, this

report regards it only as the site of the last Japanese resistance in

the Fonte area.

Where was the general's command post? It appears he had more than

one. up to July 26, he had established a command post in a natural cave

about 300 meters to the "west of Fonte." When his major counterattack

against U.S. forces on the night of July 25-26 ended in failure,

Takeshima moved from the cave "to the Fonte command post." [5] U. S. Marines commenced their attack on Fonte

on July 27. On July 28, the 21st U.S. Marinas captured all of the high

ground west of the plateau, including Mt. Mangan and the head of Fonte

River to the rear (south). That same day, the commanding general of the

III Amphibian Corps recorded that marines had captured a large command

in Target Area 561, which area is just west of the Fonte Plateau (TA

562). He added that marines had not been able to search the area because

of snipers and booby traps. [6] Also on July

28, the Third Marine Division's Intelligence Section reported that this

was the Japanese Twenty-ninth Division's command post and that it

covered from three to five acres. Finally, the U.S. Marine Corps

official history records that the 21st U.S. Marines, on July 28, overran

the 29th Division's headquarters caves, "located near the head of the

Fonte River valley close to the wrecked radio towers, and wiped out the

last defenses of Mt. Mangan as well." [7] The

conclusion is that the command post of General Takeshima's, the 29th

Division's, and General Obata's as well, is outside the boundaries of

the Fonte Unit.

General Takeshima ordered the main defense force in the Fonte area to

withdraw during the night of July 27-28 and the morning of the 28th. We

oversaw this retreat until about noon on the 28th. Then, he too withdrew

and about two hours later was killed near the north foot of Mt. Macagna.

[8]

Today, there is a large, abandoned quarry on the south edge of the

Fonte Plateau, adjacent to the concrete Japanese communications center.

It has not been determined when this quarry was first opened, but it was

in operation soon after the liberation of Guam when haste was made to

construct Admiral Nimitz's CINCPAC headquarters on Fonte. At the time

the marines captured the Fonte area another quarry existed at Mt.

Mangan. [9]

Maj. General Kiyoski Shigematsu, commander of the 48th Independent

Mixed Brigade, had his command post in this quarry and was killed there

on July 26 by US. Marines. [10]

It is not known if the U.S quarry on the Fonte Plateau destroyed the

bowl-shaped depression that held out to the last until captured by the

9th U.S. Marines. Today, east of the main quarry and south of the main

transmission line is a small depression on the plateau. The area is

excessively overgrown with lush vegetation, prohibiting a close

examination. Another depression is identified on USGS map, Sheet "Agana,

Guam" immediately north of the "Borrow Pit." Whether or not the

depression can be positively identified, the Fonte Unit is a significant

part of the national park. A 3d Marine Division battle report for July

27, 1944, when the marines had reached the nose of the plateau, said,

"the nose of FONTE RIDGE was brought under our control revealing that

FONTE is the center of the main enemy defenses of the island." [11] A marine historian described the Fonte hill

mass as the strategic high ground along the entire Final Beachhead Line.

It had been organized and defended by a battalion of Japanese. During

the fighting, another battalion and a half had been rushed into it. Its

importance may be judged by the eleven Japanese counterattacks launched

to retain it and the 800 dead left on the battlefield. [12]

In the Fonte Unit today, the prime feature is the Japanese

communications center, No. 65. Park staff has determined that the

concrete walls and ceiling of this large bunker were installed after the

battle for Guam. Other modifications have been made, including electric

lights, iron gates at the two entrances, and a plastered, wooden wall in

the northeastern corner of the main room. Within the east entrance is a

concrete platform that may well have been used by the Japanese as a

generator platform.

Besides this feature, the Fonte Unit marks a significant phase of

the battle for Guam. As a result of this action, the Japanese were in

full retreat and American forces had achieved a commanding position from

which to commence the final phase of the battle.

Today, Fonte Plateau provides a magnificent view of the entire Agana

area and inland, looking over north-central Guam.

|

|

No. 65. Japanese communications center, Fonte Plateau, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 65. Japanese communications center, Fonte Plateau, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 65. Japanese communications center, Fonte Plateau, 1984.

|

|

|

Agana as seen from Fonte Plateau, 1984.

|

|

|

A depression on the Fonte Plateau, 1984.

|

|

|

A depression on the Fonte Plateau, 1984.

|

|

|

No. 65. Japanese communications center, Fonte Plateau.

|

|

|

Fonte Plateau, Nimitz Hill, April 1945.

|

|

|

Fonte Plateau, Nimitz Hill, 1951.

|

wapa/hrs/secb.htm

Last Updated: 07-Mar-2005

|