|

BREAKING THE OUTER RING: Marine Landings in the Marshall Islands

by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret)

The Final Attack: Eniwetok

With Kwajalein Atoll now in American hands, a review

of the next operation immediately took place. Admiral Nimitz flew there

from Pearl Harbor and met with his top commanders. The 2d Marine

Division, tempered in the fires of Tarawa, had earlier been alerted to

prepare for a May attack on Eniwetok Atoll, 330 miles northwest of

Kwajalein. The planners decided to use instead the 22d Marines (under

the command of Colonel John T. Walker) and two battalions of the Army's

106th Infantry Regiment, since they had not been needed in the quick

conquest of Roi-Namur and Kwajalein. In addition, the date for the

attack was jumped forward to mid-February.

|

|

Resolute and fanatic Japanese defenders who were not

previously killed by the Marines very often committed hara-kiri, as did

the two soldiers in the foreground. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

70200

|

The softening-up process had begun at the end of

January, and the carrier air strikes increased the following month.

Japanese soldiers caught in this deluge were dismayed. One wrote in his

diary, "The American attacks are becoming more furious. Planes come over

day after day. Can we stand up under the strain?" Another noted that

"some soldiers have gone out of their minds."

On D-Day, 17 February, the Navy's heavy guns joined

in with a thunderous shelling. Then, using secret Japanese navigation

charts captured at Kwajalein, the task force moved into the huge lagoon,

17 by 21 miles in size. Brigadier General Thomas E. Watson, the Marine

in overall command of some 10,000 assault troops, had the responsibility

for conducting a complex series of successive maneuvers. As at Kwajalein

Atoll, the artillery was sent ashore on D-Day on two tiny islets

adjacent to the first key target, Engebi Island. The Marines' 2d

Separate [75mm] Pack Howitzer Battalion went to one islet, and the

Army's 104th Field Artillery Battalion went to the other. There they set

up to provide supporting fire for the forthcoming infantry assault.

The landing on Engebi came the next morning, D plus

1, 18 February, as the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 22d Marines headed

for the beach in their amtracs. At this time there occurred "one of

those pathetic episodes incident to the horrible waste of war." As one

Marine report described it:

|

|

Men

of the 17th Infantry Regiment go in by amtrac to occupy one of the

islets adjacent to Kwajalein itself in preparation for the main landing

the next day. Department of Defense Photo (Army) 187435

|

|

|

Troops of the Army's 7th Infantry Division make the

tricky transfer from their landing craft to the amphibian tractors which

will now carry them in across the reef fringing Kwajalein, for the final

leg of their assault of the island. Department of Defense Photo (Army)

324729

|

One tank was lost in the landings. It was boated in

an LCM [Landing Craft, Medium] on which, unfortunately, only one engine

was functioning. By some mischance the lever depressing the ramp was

operated with the result that the craft began to flood rapidly while

still 500 yards offshore. The tank crew had "buttoned up" and could gain

but [a] small idea of the accident. Despite the frantic efforts of the

LCM's crew to warn the occupants, the desperate urgency of the situation

was not appreciated. The LCM gradually filled, listed, and finally

spilled her load into the lagoon, turning completely over. At the last

possible moment, one of the crew of the tank managed to escape as the

tank actually hit bottom forty feet down.

|

|

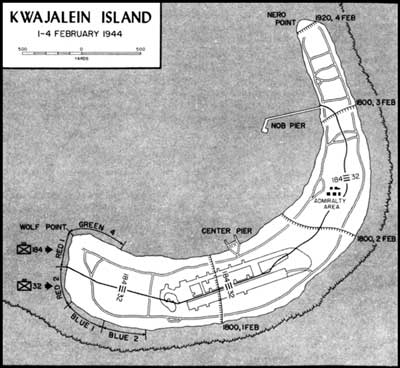

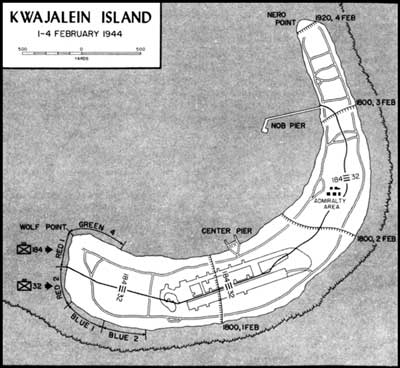

Map

of the attack on Kwajalein Island, with the landings at the west end,

184th Regiment on the left and 32d on the right. Demarkation lines show

daily progress.

|

Once the two battalions hit the beach, they found the

core of the enemy defenses to be a palm grove in the middle of the

island. This area was riddled with "spider holes," and the American

shelling had added fallen trees to the cover provided to the Japanese by

the dense underbrush. Thus their positions were extremely difficult to

locate. It was dangerous work for the individuals and small groups who

had to take the initiative, but they did and the assault ground ahead

against enemy defenses.

|

|

The

37mm gun provided invaluable direct fire support guns takes on a

stubborn Japanese position on Kwajalein, throughout the campaigns of the

Pacific War. Here, one of the reinforcing the ability of riflemen to

deal with the enemy. Department of Defense Photo (Army) 212590

|

|

|

Army

soldiers lie warily on the ground as their flamethrower pours a sheet of

fire on a Japanese pillbox. Since there were often multiple exits from

the strongpoints, these soldiers are on the alert for any of the enemy

who may try to escape. Department of Defense Photo (Army)

212770

|

|

|

Victorious Army soldiers relax by the ruins of a

Japanese plane, smashed by the preinvasion bombardment of one of the

islets adjacent to Kwajalein. One enterprising man still has the energy

and the curiosity to climb on board for a look. Department of Defense

Photo (Army) 233727

|

With these advances and some direct fire from

self-propelled 105mm guns against concrete pillboxes, the whole of

Engebi had been overrun by the Marines by the afternoon of D plus 1. On

the following morning the American flag was raised to the sound of a

Marine playing "To the Colors" on a captured Japanese bugle. An engineer

company, however, spent a busy day using flamethrowers and demolitions

to mop up bypassed enemy soldiers. More than 1,200 Japanese, Koreans,

and Okinawans were on Engebi, and only 19 surrendered.

The main action now shifted quickly on D plus 2 to

the attack on Eniwetok Island. This mission was assigned to the 1st and

3d Battalions of the Army's 106th Infantry Regiment. When they landed,

their advance was slow. Only 204 tons of naval gunfire rounds (compared

to the 1,179 tons which had plastered Engebi) hit Eniwetok. "Spider

hole" defenses held up their advance. A steep bluff blocked the planned

inland advance of their LVTAs, resulting in a traffic jam on the

beaches. Less than an hour after the initial landing, General Watson

felt obliged to radio Colonel Russell G. Ayers, commanding the 106th,

"Push your attack."

Things were clearly not going as planned, for General

Watson had hoped to secure Eniwetok quickly, and then have the

battalions of the 106th immediately ready for an attack on the final

objective, Parry Island. To speed the progress on Eniwetok, the reserve

troops, the 3d Battalion of the 22d Marines, were ordered to land early

in the afternoon. Moving forward, they were soon in heavy combat.

Japanese soldiers who had been by-passed kept up their harassing fire;

permission to bring the battalion's half-track 75mm cannon ashore was

flatly denied Colonel Ayers. The Marines had to take responsibility for

clearing two-thirds of the southern zone on the island. Tanks were

ashore but "not available," and coconut log emplacements provided the

Japanese with strong defensive positions.

Nevertheless, the attack inched forward with the

repeated use of flamethrowers and satchel charges. Halting for the night

several hundred yards from the tip of the island, the Marines were

greeted the following morning (D plus 3) by an astonishing sight. The

Army battalion supposed to be on their right flank had, without

notifying the Marines, pulled back 300 yards to the rear during the

night and left a large gap in the American lines. The Marines then had

to stem a small but furious Japanese night counterattack. When the

soldiers returned in the morning, the American attack began again, and

by mid-afternoon the Marines and the Army battalion had secured the

southern part of the island.

Progress was still very slow in the northern sector,

so Marine tanks and engineers moved in to assist the other Army

battalion there. Finally, in the afternoon of D plus 4, 21 February, the

northern area was also declared secure.

With the elapse of all this time (96 hours instead of

the 24 hours expected), General Watson was forced to alter his plans for

the final phase of the operation: the assault on Parry. He brought down

from Engebi the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 22d Marines, pulled that

regiment's other (3d) battalion off Eniwetok, and designated them for

the landing on Parry.

Amidst all of this purposeful activity, the ludicrous

side of war emerged in one episode. A U.S. float plane moored in the

lagoon, and a boat was sent to take off the crew. Coming alongside, the

boat cleverly managed to capsize the plane.

|

|

A

crater from U.S. Navy gunfire marks the left end of a series of Japanese

trenches designed to provide mutually supporting enfillade fire against

attackers. The shattered trunks of the palm trees show the effects of

the Navy's bomdardment. Department of Defense Photo (Navy) 218615

|

|

Brigadier General Thomas E. Watson

Commander of Tactical Group-1 built on the 22d

Marines, he led the conquest of Eniwetok. For this he was awarded a

Distinguished Service Medal. Promoted to major general, he received a

second DSM for his service while commanding the 2d Marine Division at

Saipan and Tinian. He retired in 1950.

With a birth date of 1892, and an enlistment date of

1912, he fully qualified as a member of "the Old Corps!" After being

commissioned in 1916, he served in a variety of Marine assignments in

the Caribbean, China, and the United States.

Given the nickname "Terrible Tommy," Watson's

proverbial impatience was later characterized by General Wallace M.

Greene, Jr., as follows: "He would not tolerate for one minute

stupidity, laziness, professional incompetence, or failure in

leadership. . . . His temper in correcting these failings could be fiery

and monumental." And so, both Marine and Army officers found out at

Eniwetok and later Saipan!

|

|

|

BGen

Thomas E. Watson, USMC, commanded Tactical Group-1, built around the 22d

Marines, as he led his Marines in the capture of Eniwetok. He later

commanded the 2d Marine Division in the ensuing Saipan-Tinian

operation. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 11986

|

|

|

|

Waves of amtracs, each one crammed with Marines

uncertain of what they will find when they hit the beach, churn in for

the assault of Engebi on 18 February 1944. They are hoping to find an

enemy dazed by the preparatory artillery fire. Department of Defense Photo (Navy)

217679

|

The exact timing of an amphibious assault is a

crucial decision based on a delicate balancing of a host of factors,

such as the condition of the troops and their equipment, provision of

fire support, etc. General Watson decided to hold off the landing on

Parry until D plus 5 (22 February). An official report explained the

reasons for the delay:

(a) To rehabilitate and reorganize [the battalion of

the 22d Marines] which had been in action for three successive days.

(b) To reembark, repair, and service medium tanks and

rest their crews.

(c) To make light tanks, which were still engaged on

Eniwetok, available for the assault on Parry Island if required.

(d) To provide one [battalion] of the 106th Infantry

as support reserve in the event it was required.

(e) To allow additional time for the air and surface

bombardment of Parry.

|

|

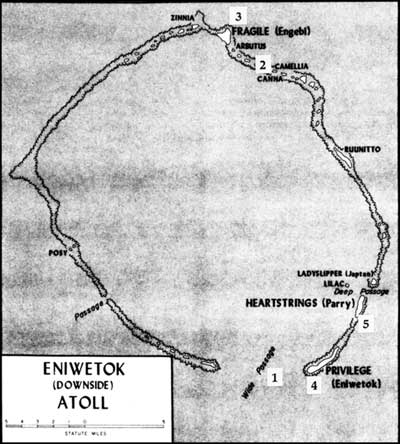

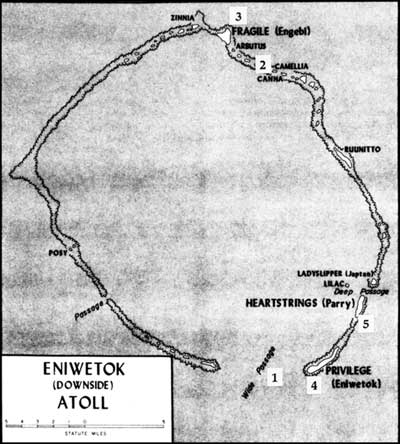

The

capture of this atoll followed a carefully planned sequence, using a

variety of geographic points; (1) entrance of U.S. ships into the lagoon

through Wide Passage in the south and Deep Entrance in the southeast;

(2) artillery set up on "Camellia" and "Canna" in the northeast; (3)

landing on Engebi in the north; (4) landing on Eniwetok in the south;

and, finally (5) landing on Parry in the southeast. RF STIBIL

|

|

|

Cpl

Anthony P. Damato, V Amphibious Corps, was posthumously awarded the

Medal of Honor for having saved the lives of his fellow Marines by

throwing himself on a Japanese hand grenade. Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

303037

|

Awaiting the amtracs of the 22d Marines, the Japanese

commander on the island issued a very succinct order to his troops:

At the edge of the water scatter and divide the enemy

infantry in their boats—attack and annihilate each one. Launch

cleverly prepared powerful quick thrusts and vivid sudden attacks, and

after having attacked and having destroyed the enemy landing forces,

first of all, then scatter and break up their groups of boats and ships.

In the event that the enemy succeeds in making a landing annihilate him

by means of night attacks.

The enemy plans to "annihilate" failed. For two days

before the Marine assault, the Navy had moved its big guns in as close

as 850 yards off shore and pounded the defenders with 944 tons of

shells. This was supplemented by artillery fire from the neighboring

islands and rocket fire from the gunboats as the Marines went in. This

rain of shells crept ahead of the tanks and infantrymen as they

tenaciously slogged their way across the island.

As always, there was the unexpected. When a shell

from a U.S. warship hit directly on top of an underground bunker, all

the Japanese inside poured out and ran—of all places—into the

sea. Another shell hurled a coconut tree aloft and catapulted the body

of an enemy sniper from its branches through the air to his death.

For the assault troops, it was a continuing story of

"spider holes," tunnels, underground strong points, and enemy resistance

to the death. Another young Marine, Second Lieutenant Cord Meyer, Jr.,

in his first combat fought on both Eniwetok and Parry. The grueling

experiences he had were typical of everyone who took part in these

battles. He was landed with his machine gun platoon in the second wave

of assault troops, three minutes after the first men to hit the beach on

Eniwetok. Moving quickly inland, the platoon came to the edge of a

blasted coconut grove. Then, as the lieutenant later wrote home:

We were hard hit there, and with terrible clarity the

reality of the event came home to me. I had crawled forward to ask a

Marine where the Japs were—pretty excited really and enjoying it

almost like a game. I crawled up beside him but he wouldn't answer. Then

I saw the ever widening pool of dark blood by his head and knew that he

was dying or dead. So it came over me what this war was, and after that

it wasn't fun or exciting, but something that had to be done.

Fortune smiled on me that day, or the hand of a

Divine Providence was over me, or I was just plain lucky. We killed many

of them in fighting that lasted to nightfall. We cornered fifty or so

Imperial [Japanese] Marines on the end of the island, where they

attempted a banzai charge, but we cut them down like overripe wheat, and

they lay like tired children with their faces in the sand.

That night was unbelievably terrible. There were many

of them left and they all had one fanatical notion, and that was to take

one of us with them. We dug in with orders to kill anything that moved.

I kept watch in a foxhole with my sergeant, and we both stayed awake all

night with a knife in one hand and a grenade in the other. They crept in

among us, and every bush or rock took on sinister proportions. They got

some of us, but in the morning they all lay about, some with their

riddled bodies actually inside our foxholes. With daylight it was easy

for us and we finished them off. Never have I been so glad to see the

blessed sun.

|

|

Poised in a shallow trench, riflemen of the 22d Marines

await the order to attack an enemy coconut-log strongpoint on Eniwetok.

While the most of the men are carrying M-1 rifles, the flamethrower in

their midst may well prove crucial. Department of Defense (USMC) 72434

|

With that battle over, the lieutenant and his men

were hustled back on ship. For a day and a night they were "desperately

trying" to get their gear into proper shape to go right back into

combat. The following morning, they went in on the attack on Parry.

They found the beach was swept with machine-gun and

mortar fire, but they surged inland over ruined, shell-blasted soil

rocked by the continual mortar bursts. Then their captain suddenly

pointed, and above the brush line they saw 150 or so men bending

forward, moving on a parallel course about 50 yards away. The Marines,

however, waved, thinking that they must be fellow Marines. The men paid

little attention to the Marines and seemed to be setting up machine

guns. The realization struck home: they were Japanese.

The lieutenant by now had just half a platoon of men

and two machine guns. They set the guns up and started firing at the

enemy. One gun jammed, so they buried the parts in the sand, because

they thought that the Japanese would charge and they couldn't possibly

stop it or prevent the capture of the gun. When they didn't attack, the

Marines moved in against them. The two sides threw grenades back and

forth for what seemed like hours. Many were killed on both sides.

Finally the lieutenant and his men threw a whole volley of grenades and

charged in and got to the beach. Down it they could see a whole group of

Japanese, so all 12 of the Marines, standing, kneeling, or lying prone,

fired their rifles and carbines. The enemy fell like ducks in a shooting

gallery, but still they closed in on the little group of Marines who

then had to back away.

|

The Deadly Spider Holes

Later accounts explained what the Marines ran into at

Engebi—and what they did to keep their advance moving forward.

Those defenses were of the "spider web" type to which

there were many entrances. They were constructed by knocking out the

heads of empty gasoline drums and making an impromptu pipeline of them,

sunk into the ground and covered with earth and palm fronds. The tunnels

thus constructed branched off in several directions from a central pit

and the whole emplacement was usually concealed with great skill and

ingenuity. If the main position was spotted and attacked the riflemen

within could crawl off fifty feet or so down one of the corridors and

emerge at an entirely different and unexpected spot from which they

could get off a shot and dive down to concealment before it was possible

to determine whence the fire proceeded. Every foot of ground had to be

gone over with the greatest precaution and alertness before these

honeycombs of death could be silenced by the literal process of

elimination.

The attacking Marines soon hit upon a method of

destroying completely these underground defenses. When the bunker at the

center of the web had been located, a member of the assault team would

hurl a smoke grenade inside. Although this type of missile did no harm

to the Japanese within, it released a cloud of vapor which rolled

through the tunnels and escaped around the loosefitting covers of the

foxholes.

Once the outline of the web was known, the bunker and

all its satellite positions could be shattered with demolitions.

|

|

|

F6F

"Hellcat" fighters from carrier decks played an important part in the

U.S. Navy's elimination of Japanese airpower on a number of islands in

the Marshalls, as well as in the devastating air strikes supporting the

assault landings. Department of Defense Photo (Navy) 80-K-100

|

|

|

In

one of the classic photographs of the Pacific War, dog-tired and

battle-grime-coated Marines, thankful to be off the island and still

alive, relax with a hot cup of coffee on board ship after victoriously

ending the bruising fight for Eniwetok. Department Of Defense Photo (USMC)

149144

|

Now the lieutenant continued his story:

But we got some tanks and reinforcements some half

hour later and moved through them in skirmish line, which brings this

tale to the most extraordinary incident of all. I was following some ten

yards behind the tanks, when a Jap officer came out of a hole pointing

his pistol at me; so instinctively I shot my carbine from the hip and

hit him full in the face. I walked forward and looked into the trench

and saw another with his arm cocked to throw a grenade. He didn't see

me. I was only six feet away. I pulled the trigger but the weapon was

jammed with sand. I had to do something, so I took my carbine by the

barrel and hit him with all my might at the base of the neck. It broke

his neck and my carbine.

Finally we killed them all. They never surrender.

Again the night was a bad one, but with the dawn came complete victory,

and those of us who still walked without a wound looked in amazement at

our whole bodies. There was not much jubilation. We just sat and stared

at the sand, and most of us thought of those who were gone—those

whom I shall remember as always young, smiling, and graceful, and I

shall try to forget how they looked at the end, beyond all recognition.

. . .

The lieutenant's letter went on to praise his

men:

They obeyed with an unquestioning courage. One of my

section leaders was hit by a bullet in his arm. It spun him clear around

and set him down on his behind. A little dazed, he sat there for a

second and then jumped up with the remark, "The little bastards will

have to hit me with more than that." I had to order him back to the

dressing station an hour later. He was weak with loss of blood but

actually pleaded to stay.

My runner was knocked down right beside me with three

bullet holes in him and blood all over his face. Stupidly I said, "Are

you hit, boy?" He was crying a little, being just a kid of eighteen, and

said, "I'm sorry, sir. I guess I'm just a sissy." I damn near cried

myself at that.

And so it went all through the day, but by evening it

was nearly all over. Early the next morning (D plus 6, 23 February)

Parry was completely in American hands, and the conquest of Eniwetok

Atoll's vital objectives was complete. Some 3,400 Japanese had been

eliminated there at a cost of 348 American dead and 866 wounded.

Mopping up operations on many of the tiny islets in

the Marshalls continued until 24 April. The troops encountered a few

scattered Japanese soldiers—quickly dispatched—and an oddity.

On one atoll they found a German who had married a native woman and had

lived there since he had originally been shipwrecked in 1891. One of the

obscure atolls was later to become famous as a U.S. nuclear testing

ground, and as a name given to a sensational new woman's bathing suit:

Bikini.

The 22d Marines had performed superbly. Recognition

of their achievements came in the form of a Navy Unit Commendation,

which praised its "sustained endurance, fortitude, and fighting spirit

throughout this operation."

Thus the Marshall Islands operations were

successfully concluded. With relatively light American casualties, a big

step had been taken in the Central Pacific campaign. U.S. forces were

now within 1,100 miles of their next objective, the Mariana Islands. The

timetable for that leap was moved up by at least 20 weeks. The 2d Marine

Division and the remainder of the Army's 27th Division were now free for

that operation, since they were not needed in the Marshalls. The basic

techniques for victorious amphibious assaults were now clearly proven.

Another large contingent of American troops had received its baptism of

fire, and the Americans had broken the outer ring of Japan's Central

Pacific defenses with impressive skill and courage.

|

The Secretary of the Navy

Washington

The Secretary of the Navy takes pleasure in commending the

Twenty-Second Marines, Reinforced, Tactical Group

One, Fifth Amphibious Corps

consisting of

Twenty-second Marines; Second Separate Pack Howitzer

Company; Second Separate Tank Company; Second Separate Engineer Company;

Second Separate Medical Company; Second Separate Motor Transport

Company; Fifth Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company; Company D,

Fourth Tank Battalion, Fourth Marine Division; 104th Field Artillery

Battalion, U.S. Army; Company C, 766th Tank Battalion, U.S. Army;

Company A, 708th Amphibian Tank Battalion, U.S. Army; Company D, 708th

Provisional Amphibian Tractor Battalion, U.S. Army; and the Provisional

DUKW Battery, Seventh Infantry Division, U.S. Army.

for service as follows:

"For outstanding heroism in action against enemy

Japanese forces during the assault and capture of Eniwetok Atoll,

Marshall Islands, from February 17 to 22, 1944. As a unit of a Task

Force, assembled only two days prior to departure for Eniwetok Atoll,

the Twenty-second Marines, Reinforced, landed in whole or in part on

Engebi, Eniwetok and Parry Islands in rapid succession and launched

aggressive attacks in the face of heavy machine-gun and mortar fire from

well camouflaged enemy dugouts and foxholes. With simultaneous landings

and reconnaissance missions on numerous other small islands, they

overcame all resistance within six days, destroying a known 2,665 of the

Japanese and capturing 66 prisoners. By their courage and

determination, despite the difficulties and hardships involved in

repeated reembarkations and landing from day to day, these gallant

officers and men made available to our forces in the Pacific Area an

advanced base with large anchorage facilities and an established

airfield, thereby contributing materially to the successful conduct of

the war. Their sustained endurance, fortitude and fighting spirit

throughout this operation reflect the highest credit on the

Twenty-second Marines, Reinforced, and on the United States Naval

Service."

All personnel attached to and serving with any of the

above units during the period February 17 to 22, 1994, are authorized to

wear the Navy Unit Commendation Ribbon.

|

|