| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

Cape Gloucester: The Green Inferno by Bernard C. Nalty The Mopping-up Begins in the West At Cape Merkus on the south coast of western New Britain, the fighting proved desultory in comparison to the violent struggle in the vicinity of Cape Gloucester. The Japanese in the south remained content to take advantage of the dense jungle and contain the 112th Cavalry on the Cape Merkus peninsula. Major Shinjiro Komori, the Japanese commander there, believed that the landing force intended to capture an abandoned airfield at Cape Merkus, an installation that did not figure in American plans. A series of concealed bunkers, boasting integrated fields of fire, held the lightly armed cavalrymen in check, as the defenders directed harassing fire at the beachhead. Because the cavalry unit lacked heavy weapons, a call went out for those of the 1st Marine Division's tanks that had remained behind at Finschhafen, New Guinea, because armor enough was already churning up the mud of Cape Gloucester. Company B, 1st Marine Tank Battalion, with 18 M5A1 light tanks mounting 37mm guns, and the 2d Battalion, 158th Infantry, arrived at Cape Merkus, moved into position by 15 January and attacked on the following day. A squadron of Army Air Forces B-24s dropped 1,000-pound bombs on the jungle-covered defenses, B-25s followed up, and mortars and artillery joined in the bombardment, after which two platoons of tanks, ten vehicles in all, and two companies of infantry surged forward. Some of the tanks bogged down in the rain-soaked soil, and tank retrievers had to pull them free. Despite mud and nearly impenetrable thickets, the tank-infantry teams found and destroyed most of the bunkers. Having eliminated the source of harassing fire, the troops pulled back after destroying a tank immobilized by a thrown track so that the enemy could not use it as a pillbox. An other tank, trapped in a crater, also was earmarked for destruction, but Army engineers managed to free it and bring it back.

The attack on 16 January broke the back of Japanese resistance. Komori ordered a retreat to the vicinity of the airstrip, but the 112th Cavalry launched an attack that caught the slowly moving defenders and inflicted further casualties. By the time the enemy dug in to defend the airfield, which the Americans had no intention of seizing, Komori's men had suffered 116 killed, 117 wounded, 14 dead of disease, and another 80 too ill to fight. The Japanese hung on despite sickness and starvation, until 24 February, when Komori received orders to join in a general retreat by Matsuda Force. Across the island, after the victories at Walt's Ridge and Hill 660, the 5th Marines concentrated on seizing control of the shores of Borgen Bay, immediately to the east. Major Barba's 1st Battalion followed the coastal trail until 20 January, when the column collided with a Japanese stronghold at Natamo Point. Translations of documents captured earlier in the fighting revealed that at least one platoon, supported by automatic weapons had dug in there. Artillery and air strikes failed to suppress the Japanese fire, demonstrating that the captured papers were sadly out of date, since at least a company—armed with 20mm, 37mm, and 75mm weapons—checked the advance. Marine reinforcements, including medium tanks, arrived in landing craft on 23 January, and that afternoon, supported by artillery and a rocket-firing DUKW, Companies C and D overran Natamo Point. The battalion commander then dispatched patrols inland along the west bank of the Natamo River to outflank the strong positions on the east bank near the mouth of the stream. While the Marines were executing this maneuver, the Japanese abandoned their prepared defenses and retreated eastward.

Success at Cape Gloucester and Borgen Bay enabled the 5th Marines to probe the trails leading inland toward the village of Magairapua, where Katayama once had his headquarters, and beyond. Elements of the regiment's 1st and 2d Battalions and of the 2d Battalion, 1st Marines—temporarily attached to the 5th Marines—led the way into the interior as one element in an effort to trap the enemy troops still in western New Britain. In another part of this effort, Company L, 1st Marines, led by Captain Ronald J. Slay, pursued the Japanese retreating from Cape Gloucester toward Mount Talawe. Slay and his Marines crossed the mountain's eastern slope, threaded their away through a cluster of lesser outcroppings like Mount Langila, and in the saddle between Mounts Talawe and Tangi encountered four unoccupied bunkers situated to defend the junction of the track they had been following with another trail running east and west. The company had found the main east-west route from Sag Sag on the coast to the village of Agulupella and ultimately to Natamo Point on the northern coast.

To exploit the discovery, a composite patrol from the 1st Marines, under the command of Captain Nickolai Stevenson, pushed south along that trail Slay had followed, while a composite company from the 7th Marines, under Captain Preston S. Parish, landed at Sag Sag on the west coast and advanced along the east-west track. An Australian reserve officer, William G. Wiedeman, who had been an Episcopal missionary at Sag Sag, served as Parish's guide and contact with the native populace. When determined opposition stopped Stevenson short of the trail junction near Mount Talawe, Captain George P Hunt's Company K, 1st Marines, renewed the attack. On 28 January, Hunt concluded he had brought the Japanese to bay and attacked. For three hours that afternoon, his Marines tried unsuccessfully to break though a line of bunkers concealed by jungle growth, losing 15 killed or wounded. When Hunt withdrew beyond reach of the Japanese mortars that had scourged his company during the action, the enemy emerged from cover and attempted to pursue, a bold but foolish move that exposed the troops to deadly fire that cleared the way for an advance to the trail junction. Hunt and Parish joined forces and probed farther, only to be stopped by a Japanese ambush. At this point, Major William J. Piper, Jr., the executive officer of the 3d Battalion, 7th Marines, assumed command, renewed the pursuit on 30 January, and discovered the enemy had fled. Shortly afterward Piper's combined patrol made contact with those dispatched inland by the 5th Marines.

Thus far, a vigorous pursuit along the coast and on the inland trails had failed to ensnare the Japanese. The Marines captured Matsuda's abandoned headquarters in the shadow of Mount Talawe and a cache of documents that the enemy buried rather than burned, perhaps because smoke would almost certainly bring air strikes or artillery fire, but the Japanese general and his troops escaped. Where had Matsuda Force gone?

Since a trail net led from the vicinity of Mount Talawe to the south, General Shepherd concluded that Matsuda was headed in that direction. The assistant division commander therefore organized a composite battalion of six reinforced rifle companies, some 3,900 officers and men in all, which General Rupertus entrusted to Lieutenant Colonel Puller. This patrol was to advance from Agulupella on the east-west track, down the so-called Government Trail all the way to Gilnit, a village on the Itni River, inland of Cape Bushing on New Britain's southern coast. Before Puller could set out, information discovered at Matsuda's former headquarters and translated revealed that the enemy actually was retreating to the northeast. As a result, Rupertus detached the recently arrived 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, and reduced Puller's force from almost 4,000 to fewer than 400, still too many to be supplied by the 150 native bearers assigned to the column for the march through the jungle to Gilnit.

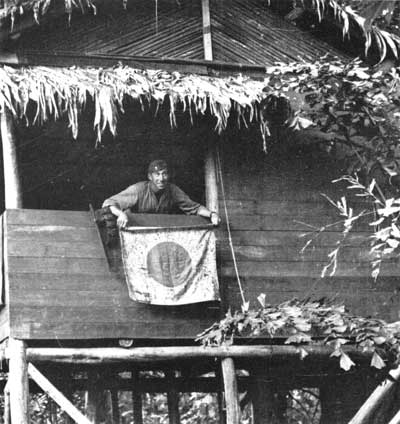

During the trek, Puller's Marines depended heavily on supplies dropped from airplanes. Piper Cubs capable at best of carrying two cases of rations in addition to the pilot and observer, deposited their loads at villages along the way, and Fifth Air Force B-17s dropped cargo by the ton. Supplies delivered from the sky made the patrol possible but did little to ameliorate the discomfort of the Marines slogging through the mud. Despite this assistance from the air, the march to Gilnit taxed the ingenuity of the Marines involved and hardened them for future action. This toughening-up seemed especially desirable to Puller, who had led many a patrol during the American intervention in Nicaragua, 1927-1933. The division's supply clerks, aware of the officer's disdain for creature comforts, were startled by requisitions from the patrol for hundreds of bottles of insect repellent. Puller had his reasons, however. According to one veteran of the Gilnit operation, "We were always soaked and everything we owned was likewise, and that lotion made the best damned stuff to start a fire with that your ever saw." As Puller's Marines pushed toward Gilnit on the Itni River, they killed perhaps 75 Japanese and captured one straggler, along with some weapons and odds and ends of equipment. An abandoned pack contained an American flag, probably captured by a soldier of the 141st Infantry during Japan's conquest of the Philippines. After reaching Gilnit, the patrol fanned out but encountered no opposition. Puller's Marines made contact with an Army patrol from the Cape Merkus beachhead and then headed toward the north coast, beginning on 16 February. To the west, Company B, 1st Marines, boarded landing craft on 12 February and crossed the Dampier Strait to occupy Rooke Island, some fifteen miles from the coast of New Britain. The division's intelligence specialists concluded correctly that the garrison had departed. Indeed, the transfer began on 6 December 1943, roughly three weeks before the landings at Cape Gloucester, when Colonel Jiro Sato and half of his 500-man 51st Reconnaissance Regiment, sailed off to Cape Bushing. Sato then led his command up the Itni River and joined the main body of the Matsuda Force east of Mount Talawe. Instead of committing Sato's troops to the defense of Hill 660, Matsuda directed him to delay the elements of the 5th Marines and 1st Marines that were converging over the inland trail net. Sato succeeded in checking the Hunt patrol on 28 January and buying time for Matsuda's retreat, not to the south, but, as the documents captured at the general's abandoned headquarters confirmed, along the northern coast, with the 51st Reconnaissance Regiment initially serving as the rear guard.

Once the Marines realized what Matsuda had in mind, cutting the line of retreat assumed the highest priority, as demonstrated by the withdrawal of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, from the Puller patrol on the very eve of the march toward Gilnit. As early as 3 February, Rupertus concluded that the Japanese could no longer mount a counterattack on the airfields and began devoting all his energy and resources to destroying the retreating Japanese. The division commander chose Selden's 5th Marines, now restored to three-battalion strength, to conduct the pursuit. While Petras and his light aircraft scouted the coastal track, landing craft stood ready to embark elements of the regiment and position them to cut off and destroy the Matsuda Force. Bad weather hampered Selden's Marines; clouds concealed the enemy from aerial observation, and a boiling surf ruled out landings over certain beaches. With about 5,000 Marines, and some Army dog handlers and their animals, the colonel rotated his battalions, sending out fresh troops each day and using 10 LCMs in attempts to leapfrog the retreating Japanese. "With few exceptions, men were not called upon to make marches on two successive days," Selden recalled. "After a one-day hike, they either remained at that camp for three or four days or made the next jump by LCMs." At any point along the coastal track, the enemy might have concealed himself in the dense jungle and sprung a deadly ambush, but he did not. Selden, for instance, expected a battle for the Japanese supply point at Iboki Point, but the enemy faded away. Instead of encountering resistance by a determined and skillful rear guard, the 5th Marines found only stragglers, some of them sick or wounded. Nevertheless, the regimental commander could take pride in maintaining unremitting pressure on the retreating enemy "without loss or even having a man wounded" and occupying Iboki Point on 24 February. Meanwhile, American amphibious forces had seized Kwajalein and Eniwetok Atolls in the Marshall Islands, as the Central Pacific offensive gathered momentum. Further to complicate Japanese strategy, carrier strikes proved that Truk had become too vulnerable to continue serving as a major naval base. The enemy, conscious of the threat to his inner perimeter that was developing to the north, decided to pull back his fleet units from Truk and his aircraft from Rabaul. On 19 February—just two days after the Americans invaded Eniwetok—Japanese fighters at Rabaul took off for the last time to challenge an American air raid. When the bombers returned on the following day, not a single operational Japanese fighter remained at the airfields there. The defense of Rabaul now depended exclusively on ground forces. Lieutenant General Yusashi Sakai, in command of the 17th Division, received orders to scrap his plan to dig in near Cape Hoskins and instead proceed to Rabaul. The general believed that supplies enough had been positioned along the trail net to enable at least the most vigorous of Matsuda's troops to stay ahead of the Marines and reach the fortress. The remaining self-propelled barges could carry heavy equipment and those troops most needed to defend Rabaul, as well as the sick and wounded. The retreat, however, promised to be an ordeal for the Japanese. Selden had already demonstrated how swiftly the Marines could move, taking advantage of American control of the skies and the coastal waters, and a two-week march separated the nearest of Matsuda's soldiers from their destination. Attrition would be heavy, but those who could contribute the least to the defense of Rabaul seemed the likeliest to fall by the wayside. The Japanese forces retreating to Rabaul included the defenders of Cape Merkus, where a stalemate had prevailed after the limited American attack on 16 January had sent Komori's troops reeling back beyond the airstrip. At Augitni, a village east of the Aria River southwest of Iboki Point, Komori reported to Colonel Sato of the 51st Reconnaissance Regiment, which had concluded the rear-guard action that enabled the Matsuda Force to cross the stream and take the trail through Augitni to Linga Linga and eastward along the coast. When the two commands met, Sato broke out a supply of sake he had been carrying, and the officers exchanged toasts well into the night. Meanwhile, Captain Kiyomatsu Terunuma organized a task force built around the 1st Battalion, 54th Infantry, and prepared to defend the Talasea area near the base of the Willaumez Peninsula against a possible landing by the pursuing Marines. The Terunuma Force had the mission of holding out long enough for Matsuda Force to slip past on the way to Rabaul. On 6 March, the leading elements of Matsuda's column reached the base of the Willaumez Peninsula, and Komori, leading the way for Sato's rear guard, started from Augitni toward Linga Linga.

|