| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FREE A MARINE TO FIGHT: Women Marines in World War II by Colonel Mary V Stremlow, USMCR (Ret) Training: Camp Lejeune Planners originally thought to use existing Navy resources and facilities for all MCWR recruiting and training, but Marines soon saw the advantage of having their own schools. It wasn't only that Mount Holyoke and Hunter Colleges were overcrowded and stretched beyond reasonable limits by the number of women arriving every week. There was a larger motive for moving MCWR schools to Camp Lejeune and, simply, it was the famed Marine esprit de corps. Camp Lejeune, where thousands of Marines were preparing for deployment overseas was the largest Marine training base on the East Coast and offered sobering opportunities for the women to observe field exercises and weapons demonstrations, and to see the faces of the young men they would free to fight. Major Hurst, commanding officer of the Marine Detachment at Mount Holyoke, understood almost immediately the drawbacks of trying to indoctrinate and train Marines in such patently civilian surroundings as a college campus. Less than a month after training began he wrote Brigadier General Waller:

Nearly a half century later, the retired 23d Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Wallace M. Greene, Jr., expressed a like sentiment when he wrote in 1990:

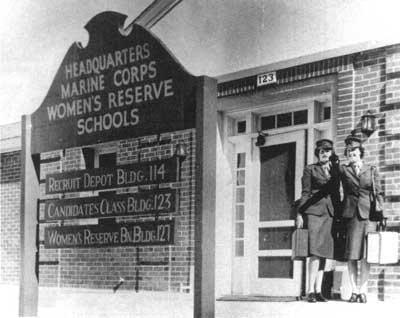

The Marine Corps Women's Reserve Schools — officer candidate and boot training along with certain specialist schools — opened in July 1943 under the command of Colonel John M. Arthur. Officer candidates and recruits in training at Mount Holyoke and Hunter Colleges were transferred to Camp Lejeune, New River, North Carolina, where nearly 19,000 women became Marines during World War II.

Just one month before the MCWR schools opened, Major Streeter asked that weapons demonstrations be made a regular part of the curricula. Frankly, she wasn't satisfied with mere classroom lectures on combat equipment, landing operations, and tactics so she tactfully suggested:

As usual, her instincts were right on target and the envious WRs attended two half-day sessions observing demonstrations in hand-to-hand combat, use of mortars, bazookas, flame-throwers, guns of all sorts, amtracs, and landing craft. The recruits traveled to Wilmington, North Carolina, on women Marine troop trains of about 500, commanded by a woman lieutenant and two enlisted assistants. They arrived at the depot as civilians, but the transition to Marines began immediately. The women were lined up, issued paper armbands identifying them as Marine "boots," ordered to pick up luggage — anybody's luggage — anybody's — and marched aboard the train. The process accelerated at the other end where they were met by shouting NCOs who herded them into crowded buses to be taken to austere, forbidding barracks with large, open squadbays, group shower rooms, toilet stalls without doors, and urinals.

The women were quartered in the red brick barracks in Area One set aside for the exclusive use of the women's schools. Their patriotism and idealism was sorely tested and some readily admit they cried when they realized what they had done. Others wondered why they had done it at all. There was, however, no time in the schedule for adjustment. General processing, medical examinations, uniforming, and classification tests and interviews to assess abilities, education, training, and work experience were top priority. Orientation classes and close order drill were scheduled for the first day and a strict training regimen kicked off with 0545 reville. One thing hadn't changed from the days at Mount Holyoke and Hunter — the male DI's weren't happy. Shaping up a gaggle of "BAMs" ("broad-assed Marines") was not what they wanted to do with a war going on. Feeling the scornful scrutiny of fellow Marines, it seemed that the DIs took on a touch more bravado than they dared on the college campuses. One boot felt the DIs resented the women, ". . . more than a battalion of Japanese troops." She was probably right. For the first year, at least, many male Marines didn't take the trouble to disguise their resentment. Disregarding the Commandant's wishes about nicknames, some Marines visibly enjoyed embarrassing the WRs with the derogatory label, BAMs. Some women took it in their stride, but it became tiresome and many were furious. When the famous bandleader, Fred Waring, referred to the WRs as BAMs, a contingent got up and walked out during a performance at Camp Lejeune. Marjorie Ann Curtner recalled a particularly mean-spirited stunt engineered by a group of Seabees who corralled every stray dog in the area, shaved them like poodles, painted "BAM" on their sides, and set them free to roam the ranks of a graduating WR platoon. For the first time in their lives, many of the women experienced the hurtful sting of coarse epithets as men vented their feelings about the Corps taking "niggers, dogs, and women." Crude language and blatant disdain took its toll on the morale of the Women's Reserve and its director, causing the Commandant to take steps to end it. In August 1943, he sent a clear message, fixing responsibility for change on unit commanding officers when he wrote:

By mid-1944 open hostility gave way to some sort of quiet truce and it wasn't long before the women's competence, self-assurance, sharp appearance, and pride won over a good many of their heretofore detractors. It was put in perspective by a young corporal wounded at Guadalcanal: "Well I'll tell you. I was kinda sore about it (the women Marines) at first. Then it began to make sense — though only if the girls are gonna be tops, understand." And, in time, Marines could even be counted on to take on soldiers and sailors who dared to harass WRs in their presence.

In September 1943, the first female hometown platoon, made up entirely of women from Philadelphia reported for boot camp. The public relations gimmick of forming a platoon of women recruited from the same area and sending them to training as a unit caught on quickly and on 10 November, the 168th birthday of the Marine Corps, the Potomac Platoon of women from Washington, D.C., and the first of two WR platoons from Pittsburgh were sworn in at fitting ceremonies. Seventeen more hometown platoons followed; from Albany, Buffalo (two), and Central New York; Pittsburgh, Johnstown, Fayette County, and Westmoreland County, Pennslyvania; Dallas and Houston, Texas; Miami, Florida; St. Paul, Minnesota; Green Bay, Wisconsin; Seattle, Washington; the state of Alabama; northern New England; and southern New England. Each platoon was ordered to duty en masse, completed boot training together, and afterwards, received individual orders to specialist schools or duty.

From 15 March 1943 until 15 September 1945, 22,199 women were ordered to recruit training and of these, 21,597 graduated. The remaining 602 were separated for medical reasons or because they were found unable to adapt to military life.

All women in the early Officer Candidates' Classes were Class VI(a) reservists recruited directly from civilian life without the advantage of enlisted experience. Consequently, for the first seven Officer Candidate Classes, the primary emphasis was on attitude adjustment, forming new habits, learning the Marine Corps "way," and adopting a military perspective. Close order drill was used to instill discipline and teach the women to respond to orders with precision. To their dismay, old salts found that the renowned tactics famous for making Marines out of civilians weren't working very well with women: shouting, "reading off," and threats were virtually useless. The methods were changed eventually, but only after the original staff members were removed. Colonel Streeter lamented that the problem was never satisfactorily resolved since there were so few experienced officers on hand to work on it and there was no time for experimentation. For approximately seven months, from December 1943 to June 1944, the Officer Training School ran on a three-block plan with two candidates' classes and a post-commissioning course, Reserve Officer Class (ROC), meeting at the same time. Each class of about 60 was organized into a company of two platoons, with a company commander and two platoon leaders. As the manpower crunch waned and the goal of 18,000 women was reached, the three-block system gave way to two-block in June 1944. with one officer candidate class and one ROC in session concurrently. A single-block plan was adopted in January 1945 and continued until the school closed on 15 October. A significant change occurred when, in July 1943, commissioned status was opened to enlisted women to take advantage of their experience, and at the same time, build morale and esprit de corps. To be eligible, a Marine had to complete six months service, be recommended by her commanding officer, and be selected by a board of male and female officers convened at Headquarters, Marine Corps. The eighth officer class, in October 1943, was made up of both Class VI(a) and Class VI(b) reservists — the latter being Women's Reserve enlisted. Thereafter, the majority of new women officers came from the ranks and from that point on, only civilian women with critical, specialized skills or exceptional leadership qualities were accepted for Marine officer training.

|