|

TOP OF THE LADDER: Marine Operations in the Northern Solomons

by Captain John C. Chapin, USMCR (Ret)

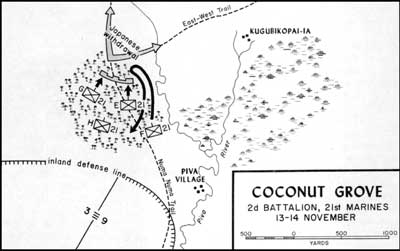

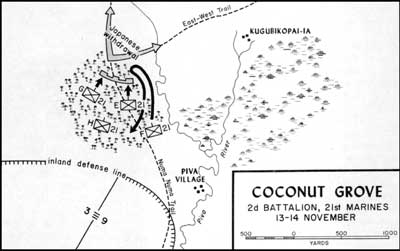

The Coconut Grove Battle

On D plus 10, 11 November, a new operation order was

issued. "Continue the attack with the 3d Marine Division on the right

(east) and the 37th Infantry Division on the left (west)." An

Army-Marine artillery group was assembled under IMAC control to provide

massed fire, and Marine air would be on call for close support.

The first objective in the renewed push was to seize

control of the critical junction of the Numa-Numa Trail and the East

West trail. On 13 November a company of the 21st Marines led off the

advance at 0800. At 1100 it was ambushed by a "sizeable" enemy force

concealed in a coconut palm grove near the trail junction. The Japanese

had won the race to the crossroads, and the situation for the lead

Marine company soon became critical. The 2d Battalion commander,

Lieutenant Colonel Eustace R. Smoak, sent up his executive officer,

Major Glenn Fissell, with 12th Marines' artillery observers. They

reported the situation as all bad. Then Major Fissell was killed.

Disdaining flank security, Smoak moved closer to the fight and fed in

reinforcing companies. (By now a lateral road across the front of the

perimeter had been built.)

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

The next day tanks were brought up and artillery

registered around the battalion. Smoak also called in 18 torpedo

bombers. The reorganized riflemen lunged forward again in a renewed

attack. The tanks proved an ineffective disaster, causing chaos at one

point by firing on fellow Marines on their flank and running over

several of their own men. Nevertheless, the Japanese positions were

overrun by the end of the day, with the enemy survivors driven off into

a swamp. The Marines now commanded the junction of the two vital trails.

As a result, the entire beachhead was able to spring forward 1,000 to

1,500 yards, reaching Inland Defense Line D, 5,000 yards from the

beach.

One important result of this advance was that the two

main airstrips could now be built. The airfields would be the work of

the Seabees. The 25th, 53d, and 71st Naval Construction Battalions

("Seabees") had landed on D-Day with the assault waves of the 3d Marine

Division — to get ready at once to build roads, airfields, and camp

areas. (They had a fighter strip operating at Torokina by December).

Always close to Marines, the Seabees earned their merit in the eyes of

the Leathernecks. Often Marines had to clear the way with fire so a

Seabee could do his work. Many would recall the bold Seabee bull dozer

driver covering a sputtering machine gun nest with his blade. Marines on

the Piva Trail later saw another determined bulldozer operator filling

in holes in the tarmac of his burgeoning bomber strip as fast as

Japanese artillery could tear it up. Any Marine who returned from the

dismal swamps toward the beach would retain the wonderment of the

"Marine Drive." It was a two-lane asphalt highway, complete with wide

shoulders and drainage ditches. It lay across jungle so dense that the

tired men had had to hack their way through it only a week or so

before.

|

|

"Marine Drive" constructed by the 53d Naval Construction

Battalion enabled casualties to be sent to medical facilities in the

rear and supplies to be brought forward easily. Photo courtesy of Cyril

J. O'Brien

|

Meanwhile, back on the beach, the U.S. Navy had been

busy pouring in supplies and men. By D plus 12 it had landed more than

23,000 cargo tons and nearly 34,000 men. Marine fighters over head

provided continuous cover from Japanese air attacks. The Marine 3d

Defense Battalion was set up with long range radar and its antiaircraft

guns to give further protection. (This battalion also had long-range

155mm guns that pounded Japanese attacks against the perimeter.)

By now, the 37th Infantry Division on the left was on

firm ground, facing scattered opposition, and able to make substantial

advances. It was very different for the 3d Marine Division on the right.

Lagoons and swamps were everywhere. The riflemen were in isolated,

individual positions, little islands of men perched in what they

sarcastically called "dry swamps." This meant the water and/or slimy mud

was only shoe-top deep, rather than up to their knees or waists, as it

was all around them. This nightmare kind of terrain, combined with

heavy, daily, drenching rains, precluded digging foxholes. So their

machine guns had to be lashed to tree trunks, while the men huddled

miserably in the water and mud. They carried little in their packs,

except that a variety of pills was essential to stay in fighting shape

in their oppressive, bug-infested environment: salt tablets, sulfa

powder, aspirin, iodine, vitamins, atabrine tablets (for supressing

malaria), and insect repellent.

|

Navajo Code Talkers

Marines who heard the urgent combat messages said

Navajo sounded sometimes like gurgling water. Whatever the sound, the

ancient tongue of an ancient warrior clan confused the Japanese. The

Navajo code talkers were busily engaged on Bougainville, and had already

proved their worth on Guadalcanal. The Japanese could never fathom a

language committed to sounds.

Originally there were many skeptics who disdained the

use of the Navajo language as infeasible. Technical Sergeant Philip

Johnston, who originally recommended the use of Navajo talkers as a

means of safe voice transmissions in combat, convinced a hardheaded

colonel by a two-minute Navajo dispatch. Encoding and decoding, the

colonel then admitted, would have engaged his team well over an

hour.

When the chips were down, time was short, and the

message was urgent, Navajos saved the day. Only Indians could talk

directly into the radio "mike" with out concern for security. They would

read the message in English, absorb it mentally, then deliver the words

in their native tongue — direct, uncoded, and quickly. You couldn't

fault the Japanese, even other Navajos who weren't codetalkers, couldn't

understand the codetalkers' transmissions because they were in a code

within the Navajo language.

|

Colonel Frazer West, who at Bougainville commanded a

company in the 9th Marines, was interviewed by Monks 45 years later. He

still remembered painfully what constantly living in the slimy, swamp

water did to the Marines: "With almost no change of clothing, sand

rubbing against the skin, stifling heat, and constant immersion in

water, jungle rot was a pervasive problem. Men got it on their scalps,

under their arms, in their genital areas, just all over. It was a

miserable, affliction, and in combat there was very little that could be

done to alleviate it. The only thing you could do was with the jungle

ulcers. I'd get the corpsman to light a match on a razor blade, split

the ulcer open, and squeeze sulfanilamide powder in it. I must have had

at one time 30 jungle ulcers on me. This was fairly typical." Corpsmen

painted many Marines with skin infections with tincture of merthiolate

or a potassium permanganate solution so that they looked like the Picts

of long ago who went into battle with their bodies daubed with blue

wood.

The Marines who had survived the first two weeks of

the campaign were by now battlewise. They intuitively carried out their

platoon tactics in jungle fighting whether in offense or defense. They

understood their enemy's tactics. And all signs indicated that they were

winning.

|

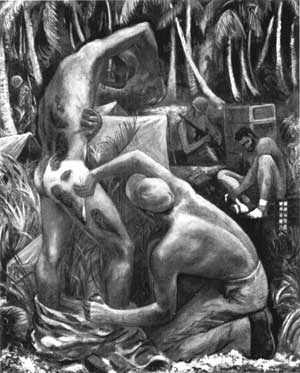

'Corpsman!'

|

|

Painting by Kerr

Fby in the Marine Corps Art Collection

|

Less than one percent of battle casualties on

Bougainville died of wounds after being brought to a field hospital, and

during 50 operations conducted as the battle of the Koromokina raged and

bullets whipped through surgeons' tents, not a patient was lost.

Those facts reflect the skill and dedication of the

corpsmen, surgeons, and litter bearers who performed in an environment

of enormous difficultly. Throughout the fight for the perimeter, the

field hospitals were shelled and shaken by bomb blasts, even while

surgical operations were being conducted.

Every day there was rain and mud and surgeons

practiced their craft with mud to their shoe laces. Corpsmen were shot

as they treated the wounded right at the battle scene; others were shot

as the Japanese ignored the International Red Cross emblem for

ambulances and aid stations.

Bougainville was the first time in combat for the

corpsmen assigned to the 3d Marine Division. Two surgeons were with each

battalion and, as in all other battles, a corpsman was with each

platoon. Aid stations were as close as 30-50 yards behind the lines. The

men from the division band were the litter bearers, always on the biting

edge of combat.

Many young Marines were not aware until combat just

how close they would be to these corpsmen who wore the Marine uniform,

and who would undergo every hardship and trial of the man on the line.

The corpsman's job required no commands; he was simply always there to

patch up the wounded Marine enough to have him survive and get to a

field hospital.

Naval officers seldom had command over the corpsman.

He was responsible directly to the platoon, company, and battalion to

which he was assigned.

Ashore on D-Day with the invading troops,

Pharmacist's Mate Second Class Andrew Bernard later remembered setting

up his 3d Marines regimental aid station, just inland in the muck off

the beach beside the "C" Medical Field Hospital. Later, as action

intensified, Bernard saw 15 to 20 wounded Marines waiting at the

hospital for care, and commented, "this was when I noticed Dr. Duncan

Shepherd . . . . The flaps of the hospital tent went open, and there was

Dr. Shepherd operating away, so calm, so brave, so courageous — as

though he was back in the Mayo Clinic, where he had trained."

On 7 December, the Japanese attacked around the

Koromokina. The official history of the 3d Marine Division described the

scene:

The division hospital, situated near the beach, was

subjected to daily air raids, and twice to artillery shelling . . . .

Company E of the 3d Medical Battalion, which was the division hospital

under Commander R. R. Callaway, USN, proved that delicate work could be

carried on even in combat. During the battle the field hospital was

attacked, bullets ripped through the protecting tent, seriously wounding

a pharmacist's mate.

|

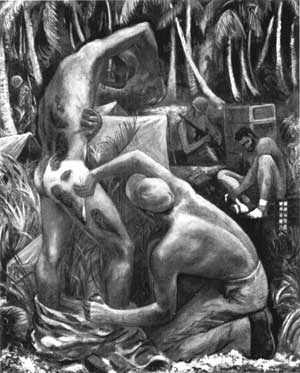

|

Painting by

Franklin Boggs in Men Without Guns (Philadelphia: The Blakiston

Company, 1945

|

Hellzapoppin Ridge was the most intense and miserable

of the battles for the corpsmen of Bougainville, according to

Pharmacist's Mate First Class Carroll Garnett. He and three other

corpsmen were assigned to the forward aid station located at the top of

that bloody ridge. The two battalion surgeons were considered

indispensable and discouraged from taking undue risks. Regardless,

Assistant Battalion Surgeon Lieutenant Edmond A. Utkewicz, USNR,

insisted on joining the corpsmen at the forward station and remained

there throughout the entire battle. The doctor and his four assistants

were often in the open, exposed to fire, and showered with the dust

thrown up by mortar explosions.

The corpsmen's routine was: stop the bleeding, apply

sulfa powder and battle dressing, shoot syrette of morphine, and

administer plasma. The regular aid station was located at the bottom of

the ridge where the battalion surgeon, Lieutenant Commander Horace L.

Wolf, USNR, checked the wounded again, before sending them off in an

ambulance, if available, to a better equipped station or a field

hospital.

Corpsmen (and Marines) were in deadly peril atop the

ridge. Corpsman John A. Wetteland described volunteers bringing in a

wounded paramarine who was still breathing when he and the medical team

were hit anew by a shell. One corpsman was killed, another badly

wounded, and Wetteland was badly mauled by mortar fragments, though he

tried, he said, "to bandage myself."

Dr. Wolf later painted a grim picture of the taut

circumstances under which the medics worked:

Several of my brave corpsmen were killed in this

action. The regimental band musicians were the litter bearers. I still

remember the terrible odor of our dead in the tropical heat. The smell

pinched one's nostrils and clung to clothing . . . . During combat in

the swamps, about all one could do to try to purify water to drink was

to put two drops of iodine solution in a canteen. Night was the worst,

when we could not evacuate our sick and wounded. But, if one could get a

ride to the air strip on the jeep ambulance to put the sick and wounded

on evacuation planes, one could see a female (Navy or Army nurses) for

the first time in many months.

|

|

|

The

155mm guns of the Marine 3d Defense Battalion provided firepower in

support of Marine riflemen holding the Torokina perimeter. National Archives Photo

111-5C-190032

|

|

|

Just

getting to your assigned position meant slow, tiring slogging though

endless mud. Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 68247

|

|