|

Whitman Mission

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER FOUR

ADMINISTRATION

Whitman Mission's managers play a very important role in the park's development. Although supervised since 1970 by the Pacific Northwest Regional Office in Seattle, each superintendent has considerable freedom to determine the park's direction and is ultimately responsible for its programs. Given this latitude, each administration reflects the priorities and interests of the superintendent. At the same time, each superintendent is influenced by his predecessor and, as a result, develops programs in reaction to what was done in the past. The following examines each administration--the administrative structure, the accomplishments, and particularly the superintendents--in order to better understand the issues and the people that have affected Whitman Mission's development as a national historic site.

Six superintendents managed the Whitman Mission National Historic Site from 1950-1987. They include Robert K. Weldon, 1950-1956; William J. "Joe" Kennedy, 1956-1964; Raymond C. Stickler, 1965-1971; Stanley C. Kowalkowski, 1971-1980; Robert C. Amdor, 1980-1987; and David P. Herrera, 1987- . Although never a superintendent, Thomas R. Garth was custodian-archeologist at the mission from 1941-1950 and was the first to have responsibility for managing the site. Therefore, this administrative overview begins with Tom Garth.

THE EARLY YEARS: THOMAS R. GARTH, 1941-1950

Administrative Structure

Even before the U. S. Government accepted title to the monument property in 1940, National Park Service representatives were planning its development. As early as 1939, engineering surveys and historical studies were under preparation for the monument's master plan. An archeological investigation was an important early step in this plan so Thomas R. Garth, a historical archeologist, was hired in December 1940 and entered on duty January 7, 1941.

Since the Whitman National Monument was coordinated with Mount Rainier National Park, Tom Garth was supervised by Maj. Owen A. Tomlinson, who was both superintendent of Mount Rainier National Park and coordinating superintendent of Whitman National Monument. Tomlinson, in turn, reported to the Region IV office, then located in San Francisco. After July 1941, Major Tomlinson was promoted to the regional director's position and John C. Preston became the new superintendent of Mount Rainier and coordinating superintendent of the monument. This was the basic administrative structure until Tom Garth transferred to the Smithsonian Institution in 1950.

Good communication existed between the three areas. Most decisions concerning the monument were made by regional personnel in consultation with the coordinating superintendent and Garth. On matters concerning future development and the master plan, regional personnel such as Olaf T. Hagen, Regional Supervisor of Historic Sites, and Landscape Architect C. E. Drysdale conducted on-site investigations. However, when it came to the actual excavating, according to Garth, "They left me pretty much on my own." [1]

Generally Garth was alone at the mission grounds except when temporary laborers helped excavate or when Marvin M. Richardson or Elmer R. Alexander, local historians and avid monument supporters, guided tours on weekends. Although Garth was employed primarily as an archeologist and only "incidentally as a custodian," [2] as the only employee on the site, he was required to do odd jobs out of necessity. When not excavating, Garth maintained the lawn around the Great Grave, checked the Monument Shaft for vandalism, and guided tours and gave lectures to visitors. In fact, visitors absorbed much of his time: "[High visitation was] maybe one of the problems. I'd get started digging and would have to stop and try to conduct the visitors around." [3]

Though varied duties were sometimes a problem for Custodian Garth, the park was not sufficiently developed nor large enough to warrant another full-time employee. In fact, almost as soon as excavations began, the Whitman National Monument essentially closed from 1942-1946 due to World War II. Garth transferred to the Permanente Metals Corporation while neighbor Ray Shelden was employed as the mission's temporary caretaker. Even after park operations resumed in September 1946, funds were scarce, even for the excavations. Thus, limited staff had to suffice. In spite of the mission's primitive stage of development from 1941-1950, due to the management skill of the regional staff and the archeological skill of Tom Garth, satisfactory progress occurred.

Principal Accomplishments: 1941-1950

At first glance the excavations appear to be the only issue that demanded management's time from 1941-1950. Although completion of the archeological work was the main accomplishment of the 1940s, several important decisions concerning the park's future were made at this time. The issues included the archeological and historical research, the Work Projects Administration, grounds development, and finally the adobe workshop/museum. An examination of each follows.

Archeological-Historical Research

While the impact of Garth's archeological work on the park's future will be discussed in the following chapter, a brief review of its progress is in order. The long-awaited archeological research recommended in 1936 by Regional Supervisor of Historic Sites Olaf T. Hagen, in 1937 by Russell C. Ewing, and in the 1940 master plan was finally realized in 1941. The April 1941 dig was the first visible sign of the National Park Service's management and development of the Whitman Mission, a moment long anticipated by local citizens such as Herbert West: "We are gratified to see work actually getting underway on restoration of the famous mission . . . . This culminates efforts of several years on the part of the Centennial group and others interested in the project." [4]

Unfortunately, little was accomplished before World War II due to lack of funds and manpower. A search for Alice Clarissa's [5] grave was conducted along the western boundary, a soil profile was taken to determine the best area for making adobe bricks, and corners of the Whitmans' First House were discovered.

The reason for the sudden shift away from archeology in 1942 was best described by Tom Garth at the time:

There is little prospect that archeological work can be resumed before the end of the war. Thus, if I am to continue work at the Monument it must be primarily historical research that I do . . . . In many ways it is fortunate to have this historical work far along before the excavations really begin. [6]

Until his transfer to the War Department, then, Garth spent the majority of 1942 researching at the University of California at Berkeley. The impact of Garth's research will be discussed in the following chapter but, in short, his research was of great help when excavations resumed.

Excavations began again in September 1946, but because of the approaching winter, only preliminary work on the First House and Mission House was accomplished.

The goal in 1947 was to locate all five major building sites before funds were exhausted. Therefore, the walls of the Mission House, Emigrant House and First House cellar walls were discovered along with the Grist Mill location and what Garth believed to be the Blacksmith Shop.

By 1948 the Mission House and the First House were excavated and recovered with soil.

Garth changed pace in 1949 when Regional Director Tomlinson recommended that he supervise the excavation of old Fort Walla Walla, soon to be engulfed by the flood waters of McNary Dam. [7] For two months in 1949, Garth excavated at Fort Walla Walla during the weekdays and Whitman Mission on weekends: "It wasn't necessary, except on weekends, to have anybody stationed at the Whitman Mission" [8] so Garth did not feel it was difficult to split his time between the two areas. When the Fort Walla Walla funds were exhausted for the year, work continued for a short time on the First House and Blacksmith Shop. The last half of the year Garth cleaned and catalogued the Fort Walla Walla specimens.

Custodian Garth completed the last archeological work in 1950 when he spent six weeks at Fort Walla Walla and a few months excavating the Mission's Emigrant House.

Except when Garth was assisted at Fort Walla Walla by Fort Vancouver Archeologist Louis Caywood and by Dr. Aubrey Neasham, Regional Historian, the excavations were conducted with minimal assistance. Three was the average number of assistants, though twelve people helped in 1947. Most assistants were untrained, often Walla Walla College or University of Washington students, and, since these students rarely worked more than one season, constant retraining was necessary each season. Since these helpers required close supervision, Garth believed that too few were better than too many.

Money was never readily available for the excavations, though lack of funds never severely hampered operations. Money flowed in spurts, at times slowing the archeological process. Usually funds were sufficient, especially during the summer when conditions were their best. Work was accomplished in spite of a tight budget.

The archeological excavations mark one of the most successful ventures undertaken at the mission during the 1940s. In contrast, one of the least successful projects at the mission was that of the Works Projects Administration (WPA).

The Works Projects Administration

Briefly, the WPA was "one of the five principal New Deal emergency relief and public works agencies [established] during the 1930s . . . ." [9] Called the Works Progress Administration until 1939, the WPA provided jobs for the unemployed; oftentimes they assisted the National Park Service. The highpoint of the WPA and other government relief programs was the 1930s; as World War II loomed closer, relief funds declined sharply. In 1941 the WPA program was reduced approximately 30 percent in funds and workers and 43 percent in operating projects from the previous year. [10] It was during this time of cutbacks that the WPA worked at Whitman National Monument.

Planning for this WPA project began in January 1940, when Herbert West inquired of Ronald F. Lee, Supervisor of the Historic Sites Branch, Washington, D. C., about the possibilities for establishing such a project at the Whitman Mission. [11] Lee's response to West was encouraging: "On examination of the Master Plan, it appears to me that the W. P. A. will probably be able to carry out certain portions of the work for the monument if proper supervision can be secured." [12]

In February, West received a letter from Arno B. Cammerer, Director of the National Park Service, supporting Whitman's WPA project. [13]

On February 23, Carl W. Smith, Acting State WPA Administrator; Regional Historian Hagen; Associate Engineer C. E. Drysdale; and Regional Inspector Primm attended a conference in Seattle to determine the feasibility of a WPA project at the monument. Results were positive:

Smith assured the group that a WPA project could be initiated during the current fiscal year provided that the sponsors could contribute 25 percent of the cost of the project in money, equipment, plans, or general supervision. [14]

Eventually a program was developed whereby all interested parties shared some responsibility for the project. The labor, the salaries and miscellaneous supplies, tools and equipment were provided by the WPA, the National Park service provided gasoline, engineering plans, and an archeologist to supervise the labor; the Walla Walla County Commissioners donated 2000 cubic feet of land-fill and a truck; while the Whitman Centennial, Inc. provided the truck drivers' salaries. Given this elaborate plan, it is not surprising that even the supervisors were confused about who was responsible for the salaries and supplies.

WPA supervisors spent from February 1940 until April 1941 determining laborers' duties. Based on the suggestions of West, WPA Engineer Hill, and WPA Project Supervisor Morrison, the project included these ambitious goals: constructing the new entrance road and parking area, fencing the mission and monument tracts, removing the barbed wire boundary fences, obliterating the existing entrance road, cleaning, and re-sodding. [15] A later addition to the proposal included "labor and equipment for archeological work." [16]

Unfortunately, the WPA accomplished only a fraction of this work since the project lasted only three months--from April 8 to June 27--before funds were terminated. Six men were employed the first month, 10 the second, and 4 the third. They accomplished small projects such as brush clearing, smoothing roads, and demolishing a fence but they had neither the equipment nor the manpower for the larger projects. As Tom Garth said, they were "kind of marking time" [17] so he took advantage of the labor and made 2000 adobe bricks for construction of a shed for tools and specimens. The adobe structure was almost complete when the project terminated, leaving Garth to finish the roof with the help of Walla Walla College students. The WPA also did some minor exploratory excavations before the project ended:

They dug one big long trench clear across the site and found the old irrigation ditch . . . also found the mill stone that probably came from the Whitman mill . . . it was actually found by one of the workmen who didn't let me know about it. He spirited it off! We later got wind of what had happened and were able to get it back. So we don't actually know exactly where it came from. [18]

Perhaps more development progress could have been made during these early years had not the monument's WPA project begun at a time when the organization was "forced to make a reduction of 40%" [19] to conform with the Emergency Relief budget cuts. As it was, WPA labor only worked three months, their contributions were negligible, and Tom Garth ended up doing the majority of work, anyway. The WPA's dubious accomplishments foreshadowed delays in the monument's grounds development that lasted for approximately 20 years.

Development

The decision to build on historic ground is a sensitive issue that requires careful consideration of the historic scene, aesthetics, and practicality. Numerous studies and plans were rejected before a development plan for the Whitman National Monument was finally deemed acceptable.

In order to understand the development proposals for the monument, it is necessary to visualize its boundaries. C. E. Drysdale, Associate Engineer, described the site in 1939:

Along the north base of the hill are graves, . . . a well and pump and hydrants for sprinkling, and two latrines. A one-way road leads from the county road along the west base of the hill to the graves where it divides, one branch ascending the hill . . . while the other branch provides access to the county road for the farmer living to the north . . . [20]

By 1940, the site included 45 acres divided by a county road; the hill, grave, and shaft were north of the road, the mission site, south. Visitors entered the grounds from the east end of the road and could drive either to the grave or to the shaft. They parked along the road and walked to the mission grounds. Farms existed to the north and south while the old Swegle house foundations stood on the mission house site. Early development plans were based on these dimensions. (see map, Appendix D)

The first preliminary master plan was approved by Acting Director Arthur E. Demaray in January 1940. [21] It included designs for a museum, custodian's residence, utility building, new road, parking area, and new fences. [22] The plan located all the buildings and the parking area on the 8-acre "Monument tract" at the base of Shaft Hill (see map, Appendix E). The design was crowded because the National Park Service had very small acreage on which to build visitor and management facilities. Evidently regional personnel believed the plan was acceptable because, according to Regional Landscape Architect E. A. Davidson, "Considerable thought has been given to this layout in preliminary form by the Regional Historian, Landscape Architect, Architect, and Engineers." [23] However, one year later, Frank E. Mattson, the new Regional Landscape Architect, voiced reservations about the limited development space: "As is usual in so many park areas, we find that the boundaries of the area do not include suitable land for development." [24] Late that year, John Preston, the mission's coordinating superintendent, inspected the site and, after conferring with Custodian Garth and "several prominent citizens of Walla Walla," [25] echoed Mattson's concerns:

I was pleased to find that the only development the Service has undertaken was paper development. All of us who visited the area recently firmly believe that considerably more study should be given to the Master Plan for Whitman National Monument. [26]

Two months later, Senior Archeologist Jesse L. Nusbaum suggested the obvious and perhaps inevitable solution--widen the park boundaries to provide for development. Nusbaum's suggestion was discussed at a conference of regional personnel:

There was general agreement to Mr. Nusbaum's suggestion regarding the advantages of a revised development plan if the boundaries of the Monument could be modestly extended by the enlargement of the monument tract to include the area across the county road from the mission site. The extension would be especially valuable in precluding the establishment of undesirable developments immediately adjacent to the mission site itself. The acquisition of additional land would also make possible improvements in the plans for the location of the residential quarters and utility buildings contemplated. [27]

While regional personnel agreed that construction and development required additional land, they did not agree about which land to develop. Archeologist Nusbaum favored the parcel directly north of the mission site. Regional engineers preferred the land west of the mission site, landscape architects preferred the land south of the mission site, while those concerned with visitor facilities favored the county road. (see map, Appendix F) [28] While Superintendent Preston recognized that "there is . . . no area that is entirely satisfactory from all standpoints for the location of the museum and administration building," [29] he realized that any of the proposals were better than crowding development on the eight-acre "monument tract." All agreed that additional property would facilitate construction of Park Service facilities and preclude private development incompatible with the historic scene.

In 1947, after World War II, Thomas Vint, Regional Chief of Development, and the other regional technicians revised the master plan and extended the monument boundaries west and east from Shaft Hill. The revised plan also closed the county road, returning it to "the old immigrant trail," Appendix G). If approved, Regional Historian Neasham predicted that "administrative, protective, and interpretive problems at Whitman should be handled with greater ease and efficiency." [31]

Despite their original support for additional acreage, by 1947 some administrators felt pressured to begin construction. They feared development would progress too slowly if dependent upon additional land. Superintendent Preston stated this view in a memorandum to the regional director:

It is no secret that the people of Walla Walla and others interested in the Monument have become impatient with the National Park Service. These good people feel that Whitman has been neglected. They want to see some action, some progress made. [32]

Regional Director Tomlinson agreed with Preston: "If [the 10-acre addition] is not acquired by the time we secure funds for the Museum-Administration building, we shall have to locate it in the next best remaining position in the Monument." [33] Custodian Garth shared his supervisor's views: "It might be feasible to consider locating the buildings elsewhere, say south of the Mission site . . . . In any event I feel that we should make building construction one of our prime objectives at the present time. [34]

While Custodian Garth, Superintendent Preston, and even Regional Director Tomlinson impatiently advocated construction, Regional Historian Aubrey Neasham refused to sacrifice the mission's historic scene for expediency:

I am still in favor of taking steps to acquire the land north of the mission building area to provide for museum and administration facilities. This is a number one priority. To put these facilities elsewhere to take care of an immediate problem is not conducive to the best interests of the long range development of the area. [35]

Thanks to Dr. Neasham's commitment, premature development was stymied and additional land became the prerequisite for development.

By the end of 1947 development progress was at a standstill since neither money from Congress nor the land on which to build was available. However, development planning made great strides. The museum and administration building, residence and utility building would be located near the "monument tract," the county road would no longer divide the monument but rather pass north of the site and the old county road would return to the Oregon Trail. These plans reflect the planning, study, and ideas of Historian Aubrey Neasham, Archeologist Jesse L. Nusbaum, Engineer Thomas Vint and others contributing to the first in a long series of decisions that affected the future of Whitman National Monument. A discussion of 1940s development is not complete, however, without mentioning a "temporary" development project that lasted 20 years.

The Temporary Museum

|

| The adobe museum (top) at it appeared in 1951. |

As aforementioned, the building known as "the temporary museum" was built by WPA labor in 1941 as a storage shed for tools and archeological specimens. As he explained to Superintendent Tomlinson, Tom Garth wanted to build the shed and use adobe bricks for construction:

In the first place, it would be much cheaper . . . . Secondly, it would give visitors an idea of what the Whitman Mission buildings looked like . . . . Lastly we will be making adobe bricks anyway to test the soil . . . we might just as well make a large number of them and use them in constructing the shed. [36]

Tomlinson supported Garth's idea but warned, "This shed can be justified only on a temporary basis." [37] Regional Supervisor of Historic Sites Hagen and Regional Inspector Primm disliked its proposed location (on the mission site, near the mill pond) and suggested moving it south of the mission site, "sufficiently away from . . . the mission area not to encroach on any historic features," [38] or building a permanent utilities building north of the county road.

Given these instructions, Hagen was understandably surprised after receiving a memorandum from Garth that stated, "We have begun to build where we had previously prepared a foundation of cement blocks and have the walls about half up." [39] Garth assured Hagen that the building "will only be in its present location a month or so" [40] and therefore would not infringe on the historic scene. Although Hagen was upset about what he considered a misuse of WPA labor and lack of consideration to historical values, he did not insist on tearing down the shed. Instead, the WPA worked on the project until their termination. While Hagen's objections were well-founded, Garth's actions were based on real needs:

Some of the Monument tools and material are stored at my home; others are stored at the office; and the remainder are temporarily stored in the shed belonging to Mr. Shelden, a nearby farmer. The adobe building is badly needed as a storage place. [41]

The shed was built because it was "badly needed" and because labor and supplies were in unusually good supply due to the Mission's WPA project. The building remained a storage shed until 1947 when Regional Historian Neasham and Superintendent Preston suggested that it also serve as a temporary museum. Thus, the building that was only supposed to exist "a month or so" existed nearly 20 years as the only building and evidence of National Park Service development, other than the excavations, on the Whitman Mission site.

Though Tom Garth was not a superintendent, major accomplishments occurred during his administration. The archeological excavations provided further information about the mission, the adobe museum was the site's first interpretive device, and preliminary development plans began. The 1940s were unique in that a war interrupted operations but did not deter planning. In fact, Regional Historian Neasham and Senior Archeologist Nusbaum made crucial decisions that protected and preserved the mission's historic scene. Plans devised during the 1940s laid important groundwork for the future.

"MODEST SCALE" DEVELOPMENT: ROBERT K. WELDON, 1950-1956

In 1950 Coordinating Superintendent John C. Preston stated that the "next logical step " [42] for Whitman National Monument was grounds development:

This phase of the work has long been neglected and is much needed inasmuch as a great amount of local criticism and other adverse publicity has resulted. No grounds improvement or interpretive work of primary importance has been accomplished . . . since its establishment as a national monument in 1936. [43]

Although unanticipated delays hampered major development, Robert K. Weldon, the first superintendent at the mission, was able to accomplish small-scale development projects that visibly improved the park's appearance. Weldon's major contributions will be examined more thoroughly following a brief overview of the administrative structure.

Administrative Structure

Robert Weldon remembers his first day at Whitman National Monument, July 23, 1950:

The July day I arrived there was one of those hot ones. I got off the bus out at the highway and sweated my way to Sheldon's [sic] farm. There I found an old International pickup (1947 model I think) with a flat tire and a dead battery. Sheldon's [sic] were pleasant and helpful -- as they always were -- and we finally got the truck running. Before I got to College Place, where I'd found a small house for us (wife and 3 children), the fan belt broke. [44]

Weldon transferred to Whitman after working at Mount Rainier National Park as district ranger since 1940. Prior to 1940, Weldon served at Hot Springs National Park, Mammoth Cave National Park, and Yellowstone National Park. In January 1956, after 5-1/2 years at Whitman, Weldon was promoted and transferred to Rocky Mountain National Park. Today Weldon lives in his native Colorado.

The monument's first superintendent received little on-site assistance during his administration. Though assisted during the summer months from 1952-1955 by a temporary ranger-historian and from 1953-1955 by a temporary laborer, the monument was "strictly a one man area as regards permanent employees." [45] Of course, Weldon was supported by the San Fransisco Regional Office and by Mount Rainier National Park. In fact, Weldon remembers very helpful personnel:

Superintendents John Preston and Preston Macy over the years would visit us at Whitman and were most helpful "up town" in handling publicity and developmental plans matters. I remember too how good we felt to have such men visit and comment as Tom Vint, Ronny Lee, Aubrey Neasham, Freeman Tilden and John Doerr. [46]

In 1950 Lawrence C. Merriam succeeded Owen A. Tomlinson as regional director. Preston P. Macy succeeded John C. Preston as superintendent of Mount Rainier and coordinating superintendent of Whitman National Monument in 1952.

Principal Accomplishments: 1950-1956

As a rule, National Park Service areas suffered after World War II from lack of funds, personnel and maintenance; the Whitman National Monument was certainly no exception. In 1950 Weldon reported that the visiting public "is often disappointed in the lack of development and appearance of the area." [47] Weldon worked hard to eliminate that criticism and as a result accomplished, in his words, "modest scale" [48] development including trails and signs, grounds maintenance, and an improved interpretive program. An examination of Weldon's major accomplishments must begin with his most time consuming task: maintenance.

Maintenance

Though superintendents are not normally found weeding and mowing in their parks, visitors to Whitman National Monument were likely to find Robert Weldon so engaged, a situation he found mildly amusing. After one month at the monument he wrote, "Well, there is always something new in the Park Service. I thought I'd just about seen and done it all . . . but goodness, no. I just finished digging out the weedy ditch . . . " [49] Today Weldon remembers those first months: "In my first monthly report I noted that 'the Superintendent began the work of watering, caring for, and pruning the grassy and shrubby areas around the Great Grave.' I might add this sort of work continued all the 5-1/2 years I was there." [50] Reaction to this newly begun routine maintenance was immediate when in 1951 a neighboring farmer reportedly remarked, "'Well, it finally looks as if someone lived around here!'" [51]

Each year specific maintenance improvements changed the park's appearance. In 1951 and 1952 the dirt paths leading to the mission sites were replaced with blacktop and a gravel footpath laid from the Great Grave to the Memorial Shaft. In 1952, water was piped to the Memorial Shaft for landscaping and the Great Grave area was refurbished. In 1953, a well, pump, and pumphouse were installed near the temporary museum for drinking water. Two pit toilets were placed near the museum while the two near the Great Grave were replaced. Weldon remembers an embarrassing situation caused by the lack of these facilities near the museum:

One day a group of girls from Walla Walla College came out. I was telling them the Whitman story by the museum when one girl started dancing around and yelling, "A bee is in my dress." So we shoved everyone out the door and she took care of the problem. Shortly after, we got a pit privy. [52]

By the end of Weldon's administration, the grounds appeared acceptable to most Walla Wallans: "Comments from some local people indicated that they were glad to see the area so well kept up now in contrast to its neglected appearance during and shortly after the war." [53] Alone, and with the help of temporary laborer Merlin B. Warner, Weldon established maintenance as a solid administrative priority. In fact, a few maintenance jobs also benefited another of Weldon's responsibilities and priorities: the interpretive program.

Interpretation

Based upon the suggestions of Ernest A. Davidson, Regional Chief of Planning, and Ronald F. Lee, Chief Historian, Washington, D. C., the excavation sites were backfilled, marked with gravel, and outlined with timbers in 1951 and 1952. [54] These markings, while simplifying maintenance, more importantly signified the first effort since the temporary museum to expand interpretation. Further expansion occurred in 1952 when the first temporary ranger-historian, Willard Whitman, was hired during the summer's high tourist season. Whitman College professor Dr. Arthur Rempel took this summer job from 1953-1954, and Burton Boylan filled the position in 1955. With the new ranger-historian assisting during the week and on weekends, the museum was open every day. Otherwise, the museum was open only when Superintendent Weldon was on the site--a very unsatisfactory situation that often irritated visitors. In fact, Mr. Weldon remembers the "fiasco" of 1952:

I had a chance to go to the Superintendent's Conference in Glacier, which I did. We could find no one to keep the Museum open, so closed it for about a week. When I got back, all hell broke loose. Visitors who found the building closed were up in arms . . . . There was some turmoil in town about the weeds, the closed building, and the "abandonment" of the area by the Park Service. What fun. A good conference but a pretty heavy price to pay. [55]

The new interpretive emphasis also resulted in a series of self-guided tour signs. Chief Historian Lee suggested modest sign development in 1950, so temporary, typed bulletins were installed until five routed historical signs, designed at Lassen Volcanic National Park, were placed at each of the mission sites in 1953. The new signs, clearly marked sites, and the temporary assistance of ranger-historians prompted Weldon to write in 1953, "We should have a good summer interpreting the Whitman story to the public." [56] In 1953 there was more to see at the monument than ever before.

By far the most unusual addition to the interpretive program was the adobe wall display, installed in 1954. Weldon described the display:

A 4 ft. long, 4 1/2 ft high section of original Whitman adobe (cellar wall of the Whitman's [sic] First House) was dug out, a cement wall built around it with glassed in top so that the adobe wall may be viewed from above by visitors . . . . [57]

This unusual and popular interpretive device remained in place until 1978. [58]

|

| The First House wall display. |

Finally, small-scale revegetation enhanced interpretation and contributed to natural resource management. Motivated, in his words, by "the policy of returning the various areas to as nearly their historic appearance as possible . . . , " [59] Weldon reintroduced native plants and grasses to the grounds which, by 1955 included, among others, willows, cottonwood, and gooseberries. Most importantly, Weldon reintroduced rye grass, symbolic of Waiilatpu yet absent from the area due to intensive farming. Also, hoping to recreate the Whitmans' orchard, "old-fashioned" [60] apple varieties, including the Winesap and Baldwin, were planted in 1955. Like Weldon's other interpretive projects, planting native species improved both short-term and long-term grounds management. While the modest development program flourished under Weldon's guidance, the major development program remained at a standstill. Although the legislative history of this issue was previously examined in chapter three, a review of development status during Weldon's term is in order.

Development

According to Weldon, major development progress from 1950-1956 "might best be described as that of a snail." [61] From 1947-1952 National Park Service officials assumed that additional land for the Whitman National Monument would be purchased by local groups for donation to, and development by, the government. As a result, money was secured for a superintendent's residence, utility building, and visitor center although the necessary land had not yet been acquired by the government. The irony of the situation did not escape Superintendent Weldon who noted, "We have money and can't spend it! What a disaster!" [62] When it became obvious in September 1952 that Walla Wallans could not afford to purchase the desired land, amendatory legislation was sought to provide for the needed acreage.

The number of acres required for development was undetermined until 1952 when Coordinating Superintendent Macy recommended securing the farm buildings north of the "monument tract" for use as a superintendent's residence. [63] Therefore, in 1952 the National Park Service sought to acquire a total of 20.7 more acres for the monument. [64] Since all major projects depended on this additional land, little else by way of major development was accomplished until the next administration. From 1950-1956 major development truly had "progressed like a snail."

Though major development was not a high point of Weldon's administration, he certainly had many achievements of which to be proud. Weldon remembers building the zigzag rail fence along the county road, replanting Whitman's apple orchard, outlining the building sites and installing interpretive signs, creating interesting exhibits, and "at least at times, getting the better of the tall, obnoxious weedy patches which caused so much bad comment." [65] In his last year as superintendent Weldon described the years 1950-1956 as the period of "grounds improvement and doubling of travel from around 10,000 annually to over 20,000." [66] Certainly Weldon made contributions in maintenance, interpretation, and public relations that set the stage for the mission's future.

CULMINATION OF DEVELOPMENT: WILLIAM J. "JOE" KENNEDY 1956-1964

If 1950-1956 are considered the years of modest development progress, then 1956-1964 should be considered the years of major development progress; major progress not only in terms of construction projects but in terms of overall park accomplishments. By 1964 the Whitman Mission National Historic Site supported a more complex administrative structure, vigorous historical research, and active community relations. Never before had such diverse accomplishments occurred during one administration. The following examines the reasons for these changes and the people responsible for them.

Administrative Structure

In response to new projects and the increased workload, the staff increased from one permanent employee in 1956 to five in 1964: the superintendent historian, administrative assistant, maintenance man, and caretaker. In addition, two laborers, three rangers, and two clerks worked part time. Like Superintendent Weldon, Superintendent Kennedy was a jack-of-all-trades and required the same of his staff. Historian Erwin Thompson remembers that his responsibilities varied:

We did everything. During the week . . . [caretaker] Merlin Warner took care of the outdoors--cutting grass, picking up trash, whatever. On Saturday and Sunday I had to do it . . . .

Joe Kennedy . . . insisted I learn everything--budget, interpretation, and just everything that was going on at the park. He insisted that his staff know what was going on . . . . [67]

In spite of the shared duties, there was a clearer distinction of work responsibility among the administrative, maintenance, and historical divisions by 1964. Caretaker Merlin Warner was "pressed into emergency guide duty" [68] during the previous administration, but such occasions were less frequent and less necessary at the end of Kennedy's term due to the enlarged staff. In addition, responsibilities that were previously the superintendent's were delegated to the staff, freeing Kennedy to focus on the major development projects finally coming to fruition after 20 years.

Important structural changes occurred at the regional level, as well. On July 1, 1956, "Whitman National Monument was decoordinated from the supervision of the Superintendent of Mount Rainier National Park [reporting instead] directly to the Regional Director of Region Four." [69] The Regional Director was Lawrence C. Merriam until 1964 when Edward A. Hummel took the job.

Partial credit for the monument's successful administrative transition and development project belongs to Joe Kennedy. Kennedy entered the National Park Service at Grand Canyon National Park in 1939. After 10 years he moved to Iowa where he was Effigy Mounds National Monument's first superintendent before transferring to Bryce Canyon. Kennedy remained at Bryce Canyon until he began his superintendent assignment at the Whitman National Monument, January 6, 1956. After 8-1/2 years he was transferred to Lava Beds National Monument in 1964. Kennedy currently resides in California.

The superintendent's role changed drastically from 1956-1964 due to the new demands of Mission 66. Unlike his predecessor Bob Weldon, who was akin to a historian and groundskeeper, Kennedy's focus was public relations. Given Kennedy's interest in the community--he was First Aid Chairman of Walla Walla County Red Cross, and a member of the Chamber of Commerce and Kiwanis, just to name a few--promoting the Whitman National Monument was a natural extension of this involvement. However, his lectures were not about the Whitman story but rather the National Park Service in Walla Walla. Unlike Superintendent Weldon who gave slide presentations on national parks, Kennedy lectured that increased visitation to Whitman Mission sparked Walla Walla's economy. He also promoted Mission 66 and reassured frustrated Walla Wallans that development was truly underway. At a time when every new change at the park was closely scrutinized, Kennedy's involvement with local people and representation of the National Park Service generated support for the park and its programs. Kennedy remembers promoting the National Park Service: "I didn't particularly care for missionaries, but I wanted the National Park Service to be thought of with respect and with a measure of affection. I hope I succeeded." [70]

Indeed, a major reason for the park's successful development from 1956-1964 was Superintendent Joe Kennedy.

Principal Accomplishments: 1956-1964

In contrast to all previous years, 1956-1964 was a time of almost frantic development. Stimulated in 1958 by the passing of Public Law 85-388 authorizing 50 additional acres for the Whitman National Monument, long-delayed construction projects began in earnest. The following list highlights 8 years of major accomplishments:

| 1958: | Public Law 85-388 passes, Congress authorizing fifty additional acres for the Whitman National Monument. |

| 1960: | Frazier farm (46.71 acres) purchased. |

| 1960-1961: | Search for Blacksmith Shop and Alice Clarissa's grave. |

| 1961-1962: | 5.6 acres for access road right-of-way donated by Walla Walla County. |

| 1962-1963: | Old county road closed; Oregon Trail restored. |

| January 1, 1963: | Name changed from Whitman National Monument to Whitman Mission National Historic Site. |

| 1963: | Residence, visitor center, and utility building constructed. |

| June 6, 1964: | New Facilities dedicated. |

Twenty years to plan, eight years to complete: the Whitman Mission National Historic Site of June 1964 looked almost entirely different from the Whitman National Monument of two decades earlier. An important impetus to this change occurred on just one day when the park nearly doubled in size from 45 acres to 98.15. This sizeable accomplishment deserves attention as do those people responsible for its occurrence.

The Frazier Farm: Last Obstacle to Development

In June 1956, after consulting with Superintendent Kennedy, Glen Frazier's son Lyle offered to sell approximately 31 acres of his property, known as Tract 11, to the National Park Service for $50,000.00 [71] (see map, Appendix H). One year later, Acting Regional Chief of Operations B. F. Manbey reported that the National Park Service preferred the entire tract. [72] To avoid splitting their property, the Fraziers agreed to sell their entire Tract 11, 46 acres, for the same price [73] (see map, Appendix I).

In response to this offer, Assistant Director of the National Park Service Jackson E. Price authorized Regional Director Lawrence C. Merriam "to negotiate an option at the best price obtainable, but not to exceed $38,000.00." [74] When the Fraziers refused to accept the $38,000.00 offer, Regional Director Merriam suggested offering $40,000.00 for the property. [75] Assistant Director Price agreed with the proposal but also recommended that "if the Fraziers will not give us an option to purchase the property for $40,000.00, we see no alternative to recommending condemnation." [76] Indeed, shortly thereafter the government filed for condemnation primarily because mineral rights belonging to former owner Dr. Cowan were discovered, preventing a simple title transfer. The National Park Service had no choice other than to refer the matter to the Federal court. Therefore, on August 3, 1959, suit was filed in the U. S. District Court for Eastern District of Washington, Southern Division for the condemnation of the Frazier Tract 11 for addition to Whitman National Monument. At the same time a Declaration of Taking of Frazier Tract 11 was filed with the taking to be effected by or before January 1, 1960. [77]

In 1959, Glen Frazier moved from Walla Walla so subsequent correspondence occurred between his lawyer, Mr. Mininick and Assistant U. S. Attorney Ronald H. Hull. While each side reevaluated their appraisals before the court hearing, Superintendent Kennedy discovered that the mineral rights belonged to the United States according to the patent issued to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1926. [78] This new information affected the property value so in May 1960, Lyle Frazier visited Superintendent Kennedy and offered to settle out of court for $45,900.00. [79] Kennedy reported that Attorney Hull responded: ". . . he will come down still further rather than go to court." [80] Just as predicted, the Fraziers dropped their offer again, two months later. In response, Regional Director Merriam teletyped to Director Wirth:

Assistant U. S. Attorney Whitaker handling case advises by letter Frazier's attorney has offered settlement at $44,000.00. Whitaker believes offer of settlement should be accepted, as award by trial jury likely to be higher. [81]

Chief of Lands Donald E. Lee agreed with this recommendation, [82] so on October 28, 1960, Regional Chief of Lands B. F. Manbey reported that "the case did not go to trial and settlement was reached at $44,000.00" [83] for the 46.71 acres of land. Four years of negotiations between the Fraziers and the National Park Service culminated in one day, doubling the size of the park and enabling the long-awaited development plans to proceed. Because of the advice of Assistant United States Attornies Ronald H. Hull and Ronald F. Whitaker, and the perseverance of Superintendent Kennedy, the plans first suggested by Senior Archeologist Nusbaum and Dr. Aubrey Neasham in the 1940s were realized--the land necessary for development of a visitor center, superintendent's residence, and utility building belonged to the Whitman National Monument.

New Approach Road

From 1947-1956, park personnel agreed that the monument's proposed entrance road should run in an east-west direction, north of the Great Grave (see map, Appendix G). Then, in April 1956, Walla Walla County Engineer B. Loyal Smith proposed a new access road aligned south from Highway 410 (later Highway 12) through the Frazier's Tract 11 [84] (see map, Appendix J). Smith assured Superintendent Macy that the County Commissioners "would be very willing and agreeable to the construction and acquisition of this necessary right-of-way if the Park Service could find some way to finance the necessary new bridge over the creek." [85] On June 7, 1956, Superintendent Kennedy, Augden, and Acting Mount Rainier Superintendent Curtis K. Skinner examined Smith's proposal and suggested a slight road realignment through Frazier's Tract 10 [86] (see map, Appendix K).

The next month, from August 1-9, Regional Landscape Architect Thomas C. Carpenter and Landscape Architect Alfred C. Kuehl from Washington, D. C., inspected the monument grounds and proposed the alignment that exists today:

We met with County Engineer B. Loyal Smith and reviewed County road problems relating to access to the Monument. Mr. Smith indicated his concurrence in our suggestion for a road route to extend southerly from Highway 410 along the west boarder of Tract 10 of the Frazier lands. [87] (see map, Appendix L)

Interestingly, this alignment was first suggested twenty years earlier by Walla Walla Trust Foundation's T. C. Elliott. According to Regional Historian Russell C. Ewing, Elliott proposed two road locations, one of which was the same route selected in 1956 [88] (see map, Appendix C).

The location confirmed, National Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth advised Regional Director Merriam of the National Park Service position regarding the proposed road:

We would prefer to place the entire right-of-way under Federal ownership and, by means of an agreement, the County would construct the approach ramp and we would be responsible for the cost of the construction of the bridge over Mill Creek . . . .

It is hoped that our design requirements for this road--with regard to such factors as width of right-of-way, control of access, elimination of roadside advertising and commercial development, and adequate insulation on U. S. Highway 410 to provide an attractive access road entrance to the Monument--will not be too high for the County to consider. It would be well, too, to try to obtain the agreement of the County to assume responsibility for the maintenance of the full length of the proposed road after construction. [89]

The Walla Walla County Commissioners agreed to these stipulations so the National Park Service signed a 20-year agreement with the Board of County Commissioners on August 28, 1961. [90] Although this formal document expired in 1981, both the park and the county still recognize this agreement which gives road ownership to the Federal government and maintenance responsibility to the county.

In spite of the agreement, development funds were allocated for archeological excavations that year to ensure that Alice Clarissa's grave did not lie in the location of the proposed road. While road construction awaited the excavation results, controversy arose over its impending construction. Property owners near the mission objected to the rezoned "Parkway" status which prevented all commercial activity for 100 feet on each side of the proposed road. Historian Erwin Thompson remembers one heated public hearing in which one man

attacked the Park Service, in general and Superintendent Joe Kennedy, in particular. I got so angry that I jumped up out of my seat and tried to defend Joe Kennedy, and the man said, "We can't hear you. Come on down front and speak in the microphone." By that time I was cooling off but I had to go down and say it all over again. [91]

The protests of the neighbors and others were in vain because the County Commissioners agreed to the "no commercial development" provision in their August 1961 agreement with the National Park Service. The County finally dropped the road's "Parkway" zoning prior to 1980 as part of a county-wide zoning consolidation effort; the historic scene is not threatened because the Federal government will not allow commercial activity along the road. In a related issue, College Place residents protested closing the old county road and converting it to the Oregon Trail because "a dead-end road, stopping near the Monument, would virtually shut off the area to Walla Walla College students and residents of the community." [92] Rather than a dead end road, they suggested a turnaround and parking area, and a walkway through that section of the park. [93] A February 20, 1962 Union-Bulletin article reported that Superintendent Kennedy "promised there would be a turnstile through the fence . . . ." [94] By May 1963, a "walk-through" stile was built. [95]

After the road controversies subsided and funds materialized, a contract for the Mill Creek bridge was awarded to Hans M. Skov Construction Company of Yakima on May 21, 1962. [96] The bridge, designed by B. Loyal Smith and constructed under his supervision, was completed October 8, 1962. [97] By June 1963, the new park approach road was paved [98] and by May 8 the old county road permanently closed. [99]

After 22 years of deliberation, the new access road was completed. Proposed locations for the road varied over the years--from the Church Tract in 1941 to the Great Grave in 1950. Several people deserve credit for finally determining the best location for the road and completing the project. In 1936, Regional Historian Ewing concurred with T. C. Elliott's suggestion to build the road from Highway 410 along the Frazier Tract 10. The enthusiastic and cooperative B. Loyal Smith not only reminded National Park Service employees of this option, but designed and built the road and bridge. Finally, Regional Landscape Architect Carpenter and Washington, D.C., Landscape Architect Kuehl deserve credit for making the final decision in 1956. Thus, by 1963 the Whitman National Monument had more land, a new road, new archeological excavations, and, by January of that year, a new name: The Whitman Mission National Historic Site. Building construction, by far the most visible change, occurred that same year, as well.

Mission 66: Long-Term Construction Progress

Whitman National Monument's delayed development was a typical problem of National Park Service areas after World War II. National Park Service administrators struggled for ten years trying to reorganize their parks after the war; Superintendent Weldon's administration is an example of this effort. When conditions had not improved by 1955, National Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth responded by initiating a long-term national recovery program for the National Park Service called Mission 66. This ten-year rehabilitation program was designed to improve facilities, staffing, and resource preservation at all areas in time for the 50th anniversary of the Service. [100] Congress provided an estimated $786 million for the ten-year program. [101] The Whitman National Monument development project cost $451,300.00. [102] Assigned to the Whitman National Monument the same year the Mission 66 program began, Superintendent Kennedy had as his primary responsibility overseeing Mission 66 development at Whitman Mission. After Public Law 85-388 provided the needed land for construction in 1958, new project ideas flowed from administrators in anticipation of the impending development.

|

| Proposed development site -- the base of Shaft Hill circa 1940. |

The monument's "Mission 66 Prospectus" planned for superintendent's and historian's residences. On May 9, 1958, Superintendent Kennedy recommended new locations for these buildings. Rather than locating them "easterly of the Frazier residence and a little to the north of the present Monument boundary" [103] Kennedy suggested a more visible location to deter vandalism: "I feel that if the residences are to be constructed they should be placed in sight of the Mission Grounds . . . . I suggest a location near the present Frazier buildings." [104] Rather than constructing a combined utility building and visitor center: "It might be better to have the utility building separate . . . to place it a little east of the residence out of sight of the Mission Grounds." [105]

Regional Director Merriam concurred, and these revisions were incorporated into the park's master plan.

National Park Service Director Wirth visited Whitman National Monument in 1960 to check on the park's Mission 66 progress. Certainly a noteworthy occasion, Director Wirth's visit was made more memorable when, at a reception given by Superintendent Kennedy and his wife, "[Director Wirth] helped catch the sheep that jumped over the fence into our yard while we were having cocktails and a picnic dinner." [106] When not busy rounding up sheep, Director Wirth suggested a few changes to the park's development plan. He objected to the visitor center's proximity to the mission site and the parking area's proximity to the Great Grave:

Mr. Wirth suggested that the visitor center be moved northward approximately 400 feet and one parking area designed to serve both visitor center and the Monument . . . . A trail from the monument [on Shaft Hill] southward to the historic Oregon Trail was also suggested. This would permit a circulatory walk to all the important features from the one parking area . . . . [107]

Director Wirth's suggestions and those of Regional Director Merriam and others were incorporated into the "General Development Plan" and approved by Superintendent Kennedy, Regional Director Merriam, Chief of Design and Construction Vint, and Director Wirth on August 31, 1960 (see plan, Appendix M). This layout combined with the master plan narratives written by Kennedy provided the basis for construction from 1961-1963.

Construction: First Phase

Construction proceeded in three main phases. During the first phase, a contract for roads, trails, parking areas, and utilities was awarded to Edward Mardis of Walla Walla in 1961. [108] Supervised by Herbert Quick, Project Officer from the Western Office of Design and Construction, San Francisco, and assisted by Thomas L. Weeks, Landscape Architect from Washington, D. C., several projects were completed by June 1962. The parking and picnic areas were constructed, two septic tanks installed, a 50,000-gallon reservoir built on Shaft Hill, the irrigation ditch and millpond dikes were restored, and the millpond filled with water for the first time since the Whitman era.

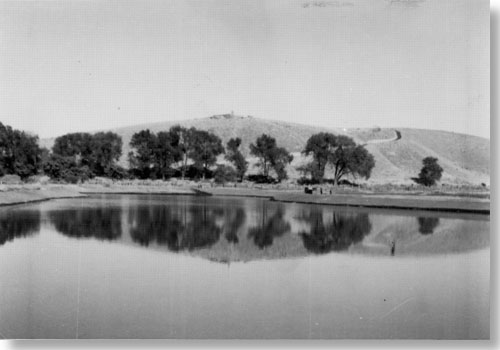

|

| The millpond as it appeared to National Park Service officials in 1936. |

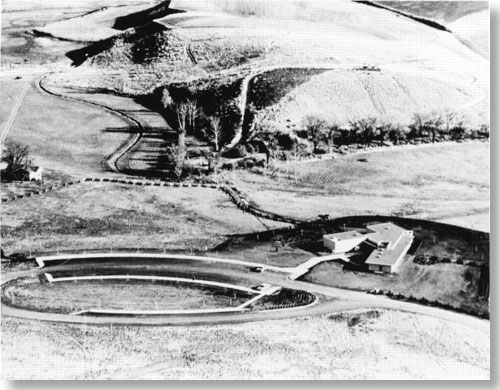

|

| The millpond as it appeared after 1961. |

Construction: Second Phase

The second phase of construction began in 1963 and included two contracts--one for the visitor center and utility building, the other for a three-bedroom residence. Two invitations to bid were issued for the visitor center since the lowest bid was 10 percent over the government estimate. [109] Both contracts were finally awarded Mr. Mardis and supervised by Project Supervisor Robert F. Smith. [110] After eight months of construction, the visitor center opened to the public on September 28, 1963. [111] This building also provided administrative offices, previously located in the temporary museum in 1956, in a house trailer near the temporary museum from June 1957 to September 1961, and finally in the Frazier residence in 1962. While the new visitor center finally alleviated the cramped office space problem, the new utility building, constructed from January-May, solved many long-term storage problems. [112]

In 1961, W. A. Bailey of Walla Walla removed the Frazier farm buildings in preparation for construction of the three-bedroom residence. [113] The residence was built from March-May 1963; Superintendent Kennedy moved in on May 29. [114] The next step was remodeling the old Frazier residence into the historian's residence, but in 1964 the decision was made to forgo remodeling and, instead, remove it altogether. In April 1964, the house was sold to Mr. W. F. S. Nelson of Walla Walla and removed by May 28. [115] By the end of 1964 the historian's residence was planned but not built.

Construction: Third Phase

The third and final phase of development included a landscaping contract awarded in 1963 to Staneks, Incorporated, of Spokane. [116] Supervised by Project Supervisor Thomas L. Weeks, Washington, D. C., these jobs included planting lawns around the visitor center, laying trails and sidewalks, installing sprinklers and restoring the Oregon Trail. [117] When Staneks, Inc., obliterated the temporary museum in October 1963 [118] its destruction symbolized the passing of an era in facilities used to manage the Whitman Mission National Historic Site.

Whitman Mission National Historic Site's Mission 66 program culminated on June 6, 1964, with the dedication of the visitor center. More than one thousand guests attended the ceremonies in a tribute to the successful development. The dedication culminated not only the work of Director Wirth, Superintendent Kennedy and the mission and regional staff, but included the work of all those who since 1941 strove to make the Whitman Mission development project a reality.

|

|

Development site after visitor center and trails were completed in 1963 but before the Frazier house was removed in 1964. |

Historical Research and Interpretation

Although certainly an important aspect of Kennedy's administration, construction was not the only significant accomplishment during 1956-1964. Important historical research was accomplished during these years due to Park Historians George Tays, Jack Farr, Erwin Thompson, and John Jensen. Historian Tays mapped the building sites and Historian Farr began writing the museum prospectus and historical handbook, both of which were completed by Historian Thompson in addition to his own study of the mission house kitchen. Thompson remembers that lack of funds and resources hindered research so he had to make do with what they had. He remembers, "The two colleges were our greatest help. Then we got the [Whitman-American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions correspondence] microfilm from Yale University and that helped a lot." [119] These resources were especially useful when the museum was constructed:

[The museum planners] . . . would send up requests--"What ages were the . . . Sager children?" . . . "What kind of clothes did they wear at that time?" and so forth. Then I would busy myself around here, Whitman College and sometimes go up to Pullman and try to find the answers for their questions, and that varied from minute research to some fairly complex jobs. [120]

In addition, artifacts for the museum were acquired during these years, including Elizabeth Sager's "papoose" doll and a lock of Narcissa Whitman's hair. Aside from their research and writing, each historian guided tours and interpreted the site for visitors until 1964 when tours were phased out and the site became truly self-guiding. In no way should the years 1956-1964 be considered only in terms of construction, but rather, in terms of development which encompassed important historical research and interpretation, as well.

Planning, research, changes in the park's administrative structure and physical appearance were all achievements of 1956-1964. "Exciting" was the word Erwin Thompson used to describe those years. "We knew great things were happening," he said. [121] Today Kennedy credits their success to "a good, strong program worthy of support" [122] and to his staff, Regional Directors Lawrence C. Merriam and Edward A. Hummel and their staffs, and finally Walla Wallans Allen Reynolds, B. Loyal Smith, and Vance Orchard. Kennedy also remembers his own place in those busy years:

For me, Whitman was a real challenge. It was so bleak when we arrived there that January day in 1956 . . . and Whitman was so beautiful and kind of shining when we left eight and one-half years later! I had worked my tail off, but I had enjoyed it. Some of the fights had been bitter but we had always won, always, because we were always on the right side. [123]

Or as Superintendent Stickler said of the park's development in 1966, "It was a good 'package plan' rather than a piecemeal operation." [124] The accomplishments of 1956-1964 changed the park's direction forever. The process of development was finished and the process of management begun. As Park Historian John Jensen aptly wrote in 1965, "[These accomplishments] marked the start of a new era in operation of the Park--a change from a program of research and construction to one of interpretation and maintenance." [125] How the next administration coped with these changes and new responsibilities is the subject of the following section.

A TIME OF TRANSITION: RAYMOND C. STICKLER, 1965-1971

The Mission 66 developments not only transformed the mission's inadequate, makeshift facilities to attractive and efficient facilities," [126] but they also transformed administrative responsibilities. Superintendent Stickler said:

Now that the physical development of the Park has been completed, the interpretive and public relations programs require the most attention and emphasis. Maintenance operation and improvements of the Park grounds and facilities have become more or less routine. [127]

The 1965-1971 administration searched for ways to utilize their new facilities. Larry Dodd, curator of the Whitman College Archives and ex-park ranger, remembers a time of transition: "We were trying to understand what was needed." [128] As the staff searched for new direction, they attended to details that had thus far been overshadowed by the major construction projects. As a result, modest improvements occurred in the various divisions, beginning with the administrative organization.

Administrative Structure

Raymond C. Stickler entered on duty as superintendent of Whitman Mission National Historic Site in February 1965. Familiar with the area, Stickler was born in Pendleton, Oregon, and had many relatives in the Walla Walla valley. Employed by the National Park Service since 1939, except during World War II, Stickler held several administrative positions at Crater Lake National Park [129] and had served since 1951 at Olympic National Park prior to transferring to the Whitman Mission. Superintendent Stickler served in Walla Walla for five and one half years before his untimely death on July 8, 1971.

Stickler followed Kennedy's example of placing priority on public relations. His active participation in the Walla Walla Rotary, Toastmasters, and the Chamber of Commerce, and his presentations to groups like the Marcus Whitman Foundation, the Walla Walla Archaeological Society, and the Walla Walla Valley Pioneer and Historical Society, encouraged contact between the community and the mission. The superintendent no longer remained solely on the park grounds, but was free to travel and was involved with regional and community events.

A few administrative changes occurred during Superintendent Stickler's term. Edward A. Hummel became regional director in 1964, but was replaced a few years later by John A. Rutter. In 1969, the Regional Office headquarters moved from San Francisco to Seattle, where it remains today. The park's administrative structure did not change from 1965-1971. The five positions included superintendent, historian, administrative assistant, maintenance mechanic, and maintenance worker. With the ever-increasing number of seasonal rangers and laborers, the permanent staff was freer to attend training seminars and pursue projects off the park grounds. Superintendent Stickler and Historians Jensen and later Robert Olsen attended training sessions in California, Colorado, and Washington, D. C. Emphasis on efficiency and productivity resulted in weekly priority lists for interpretive and administrative work. This effort to document work progress culminated in 1971 with the Service's emphasis on "management by objectives." The new use of objectives and an enlarged staff reflect the administrative structure from 1965-1971.

Principal Accomplishments: 1965-1971

The projects accomplished from 1965-1971 were based on the needs outlined in the 1964 revised master plan, and on the goals outlined each year by Superintendent Stickler. Most progress occurred in the interpretive division since there was a decreasing need for research and an increasing need for varied interpretive programs. The transition from the position of "Historian" to the position of "Supervisory Park Ranger" in 1966 is an indication of this change. In contrast, the maintenance division received little attention because, as mentioned before, Superintendent Stickler felt maintenance was of a "routine" nature and required little improvement. For example, maintenance goals were not set in 1968: "It was not necessary to prescribe specific goals in this program other than to assure that the present quality of maintenance continues." [130] Therefore, an examination of Stickler's priority, interpretation, is in order.

Interpretation

With a new visitor center and museum, the devices for interpreting the Whitman story were better than ever. However, both Historian John Jensen and Assistant Regional Director James Myers suggested additional improvements. Both Jensen and Myers recommended an audiovisual slide-tape program about the Whitmans, [131] so Historian Jensen researched facts for the script in 1965. [132] Although this Whitman slide program remained a priority for several years, it was not completed until the next administration. In the meantime, the rangers made their own slide programs to show visitors. "Each one of us could do our own thing," said Larry Dodd. "We were interpreting the site as we saw it." [133]

Another interpretive priority was cataloging not only the specimens uncovered in the Waiilatpu dig, but also those found during the Fort Walla Walla excavation. In 1967, almost 900 hours were spent identifying, sorting, and cataloging the Fort Walla Walla artifacts by the staff, a group of Girl Scouts, and an archeological student, Gregory Cleveland, from Washington State University. [134] Stickler explained in 1968, "Through arrangements made by the Regional Archeologist, artifacts having no relation to the Whitman story were shipped to the University of Washington and Washington State University." [135] The Waiilatpu artifacts were catalogued from 1967-1969 by Historian Robert Olsen, assisted by Park Rangers Jack Winchell, Larry Dodd, and others. Dr. Roderick Sprague, University of Idaho, preserved the specimens while Regional Curator Edward Jahns supervised the project. Preserving and cataloging the artifacts not only protected them, but helped familiarize interpreters with the Whitman story.

Another improvement in the interpretive program included the construction of a display case for temporary exhibits. Designed to "interpret details and stories not covered in the permanent exhibits," [136] this case was first suggested in the 1964 master plan and built and installed by maintenance man Charles Dims in 1966. [137] Larry Dodd remembers displaying the Pair Collection, and items such as Narcissa Whitman's writing desk were loaned from the Oregon Historical Society for display in later years.

On April 28, 1968, the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin reported "A monument was placed at the Whitman Mission National Historic Site . . . by the Marcus Whitman Foundation honoring the grave of Alice Clarissa Whitman, daughter of Dr. and Narcissa Whitman." [138] This presentation followed Western Regional Archeologist Paul Schumacher's excavations possible grave sites in 1960-1961. Despite the marker, the exact location of the child's grave is unknown.

In June 1968, in an effort to protect geese endangered by the raising of the John Day reservoir, the Washington State Game Department released fifty pairs of geese in Walla Walla--many of them at the Whitman Mission. [139] Their wings were clipped to prevent them flying away; a fence was built to prevent them from walking away. This effort established Whitman Mission as a sanctuary geese return to each year.

In 1970, Historian Robert Olsen finished his comprehensive study, "Report on Whitman Mission China." That same year, Whitman enthusiast Ross Woodbridge concluded that the sketches he discovered in Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum in 1968 were of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. [140] While Historian Clifford Drury was convinced by the "strong circumstantial evidence," [141] neither Superintendent Stickler nor any other National Park Service personnel accepted the sketches as authentic. [142] Nevertheless, the sketches hang in the visitor center today as the most plausible likenesses of the Whitmans that exist.

Miscellaneous interpretive projects, including placing new signs, planting more rye grass, and maintaining the historic orchard continued throughout Stickler's administration. However, none of these aforementioned changes drastically changed the interpretative program at the park.

Development

Though development was not a major issue after the Mission 66 construction projects, the status of forty acres west of the monument grounds was still in question in 1965. The 1964 master plan revised by Raymond Stickler and approved by Acting Regional Director Warren F. Hamilton in 1965 recommended that "Immediate steps should be taken to secure legislative approval to increase the authorized acreage of Whitman Mission sufficient to provide for the acquisition of the forty acre farm." [143]

This suggestion was based on objections to neighbor Ray Shelden's 40-acre operation "immediately adjacent to and west of the Mission site" which James Myers described in his 1965 Appraisal Report as an "unfortunate intrusion on the historic scene." [144]

In March 1966, Mr. Sheldon purchased forty more acres adjacent to his farm and the park from Glen Frazier. [145] By July, Regional Director Hummel discussed with Superintendent Stickler the possibility of acquiring scenic easements rather than the recently expanded farm. [146] However, since Sheldon and his son planned to farm the land, by 1971 all designs for acquiring the acreage were dropped: "There are no plans to acquire additional land for inclusion in the area." [147]

One final development project remained unfinished in 1965. According to the 1965 revised master plan, the historian's residence, planned for Fiscal Year 1967, was needed "to insure service personnel in the Park most of the time to deter any vandalism and to provide adequate fire protection" [148] However, Superintendent Stickler wrote in the 1971 management objectives, "There is no immediate need for the additional residence, although it is retained in the construction program." [149] One residence provided adequate protection against vandalism and intrusion, so the mission's last development project remained a paper development project only.

With the Mission 66 facilities completed by 1964, Superintendent Stickler's administration focused on maintaining the status quo rather than development. "Whitman Mission was pretty stable . . . . Nothing much was happening at that time," said Larry Dodd. [150] As a result, the staff attacked several time-consuming projects such as public relations, cataloging artifacts, and constructing extra display cases. This attention to detail resulted in a more polished interpretive program, a more organized management division, and a busy maintenance staff. This new emphasis on perfecting park operations quickly set the precedent for the following administration.

MAINTAINING THE STANDARD: STANLEY C. KOWALKOWSKI, 1971-1980

The character of the 1971-1980 administration remained similar to that of previous years. The transition from Superintendent Stickler's administration to Superintendent Kowalkowski's was smooth and uneventful. In fact, Kowalkowski concludes today that, "My contribution was maintaining what had been established." [151] While it is true that Kowalkowski maintained the accomplishments of the past, his administration was responsible for innovations in interpretation that characterize the program today. Before examining this significant contribution more thoroughly, the administrative structure deserves note.

Administrative Structure

Administrative changes occurred from 1971-1980 including the number of permanent staff. In addition to the superintendent, administrative clerk, supervisory park ranger, maintenance mechanic and maintenance worker, a permanent park technician was hired in 1978. The temporary staff included an information receptionist who assisted the administration, while varying numbers of seasonal rangers and laborers, usually from three to five, expanded the interpretive and maintenance divisions. Finally, volunteer and YACC-enrollees helped the staff during the busy summer months. Guidance from Seattle came from Regional Director John A. Rutter and from his successor, Regional Director Russell E. Dickenson. This staff included more women and minorities than in previous years due to new Equal Opportunity Employment requirements undertaken during this administration.

Stanley C. Kowalkowski left his superintendent position at Booker T. Washington National Monument in Virginia to accept the superintendent position at Whitman Mission, August 30, 1971. Kowalkowski worked previously at the Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia, at Yosemite National Park in California, and Everglades National Park in Florida. Kowalkowski retired from the National Park Service in 1980 and currently resides in Walla Walla.

Principal Accomplishments: 1971-1980

The maintenance program received renewed attention from 1971-1980. In 1978, Kowalkowski reported, "We believe that we are developing a sound, valid long-range cyclical maintenance program." [152] The walks were paved with exposed concrete aggregate rather than asphalt for a more asthetically pleasing look, 80 percent of the millpond bank was repaired with river rock and sand, and a new visitor center air conditioner was installed. An effort was also made to document maintenance procedures and programs. However, the majority of maintenance was limited to tending the lawns and other landscaping jobs.

In spite of these accomplishments, improving interpretation was administration's main focus. The mission's new interpretive activities called cultural demonstrations, in which rangers demonstrate pioneer and Indian skills, sparked visitor and community interest. Before transferring to Whitman Mission, Superintendent Kowalkowski developed a similar "living historical farm" program at Booker T. Washington National Monument. [153] However, when discussing his part in Whitman Mission's cultural demonstration program, Kowalkowski claims only a supportive role:

I relied heavily on the people who worked at Whitman . . . . Chief Interpreter [Larry Waldron] . . . was the person who ram rodded things, who saw to it that certain ideas were carried out. In most cases I was quite supportive . . . and we were happy with the results. [154]

Examination of this program and other important interpretive developments follow.

Interpretation

The most obvious and far-reaching change in the interpretive program was the experimentation with "living history" through the use of cultural demonstrations. "We are trying to make history come alive," stated Chief Park Interpreter Larry Waldron in 1972. [155] Four volunteers were recruited that year just to demonstrate the pioneer skill of spinning wool. Pioneer cultural demonstrations continued each year and by 1979 included wool-spinning, adobe brick-making, wool-dyeing, candle-dipping, soap-making, and "nooning on the Oregon Trail." [156] During the summer of 1975 Ron Marvin, a Washington State University teaching assistant, was hired to play the role of an immigrant on the Oregon Trail. [157] In 1978 June Cummins was hired permanently to demonstrate pioneer skills. Kowalkowski's cultural demonstration programs lasted beyond his administration and remain a stable part of the mission's interpretive program today.

Progress presenting a more balanced view of the Whitmans' eleven years at Waiilatpu was made when Native American demonstrations were developed early in Kowalkowski's administration. In the 1972 Annual Report Kowalkowski wrote: