|

Whitman Mission

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER FIVE

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Management of the cultural and natural resources is an important administrative responsibility. The 1986 "Resource Management Plan and Environmental Assessment" lists Whitman Mission National Historic Site's most significant cultural and natural resources:

- The historic ground itself, the site of the Mission is a National Register property with many artifacts in situ.

- The restored Mill Pond and a portion of the original irrigation system, the Great Grave, the Memorial Shaft on the hill, and the section of the Oregon Trail are on the List of Classified Structures.

- The re-established orchard, the river Oxbow, the cemetery used by the Indians, pioneers and emigrants, and the Alice Clarissa Memorial are within the boundaries.

- Over 10,000 irreplaceable artifacts are in the study collection and all are direct touchstones with our enabling legislation.

- Several thousand historic and modern photographs, along with Park library and archival files, make up the most complete records of the site's history.

- The Shaft Hill provides a surrounding view of uncluttered landscape. Rolling eastward up to the Blue Mountains, the Walla Walla Valley has many visual characteristics unchanged from the time of the Whitmans. [1]

This chapter addresses administration's role in preserving these cultural and natural resources. The first section covers cultural resource management plus archeology, because archeological discoveries influenced the ways in which superintendents managed these resources; the second section covers natural resource management.

CULTURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

In the park's early years, active management of the resources occurred rather sporadically when the superintendent perceived a need. Then, in 1982, increased attention to cultural resources occurred service-wide due to Director Dickenson's commitment that all parks have high quality resource management plans. [2] Completed in October 1982, and updated each year, Whitman Mission's "Resource Management Plan" currently provides the most specific instructions and direction for cultural resource management. The following section outlines some of the cultural resource problems facing management since 1940 and examines the varied methods used to solve those problems. This overview begins by discussing the important role archeological discoveries played in assisting cultural resource management.

Two separate archeological excavations occurred at Whitman Mission National Historic Site. The first, briefly outlined in chapter four, was conducted by Thomas R. Garth between 1941-1950. The second, directed by Paul J. F. Schumacher, was conducted from 1960-1961. An explanation of the reasons for each excavation, their results, and their impact on the cultural resources follows, beginning with the 1941-1950 excavation.

|

| Tom Garth (second from left) and crew excavate the mission house in 1941.> |

Archeology: 1941-1950

The 1941-1950 excavation was the first development project completed at the Whitman National Monument. In 1938 Olaf T. Hagen, Regional Supervisor of Historic Sites, explained that excavating the mission site was top priority in order to ensure "that new development would not intrude on parts of the historic area." [3] Excavation was also required before serious consideration could be given to the idea of reconstructing the mission buildings. Therefore, custodian-archeologist Tom Garth excavated the mission site from 1941-1950; because of World War II the bulk of work was accomplished from 1947-1948. When the project neared completion in 1950, the first house, mission house, emigrant house, gristmill, and blacksmith shop had been examined, although very little evidence of the blacksmith shop was discovered. More than 2,000 artifacts were unearthed and preserved from these excavations, including medical supplies, china sherds, and metal fragments. While complete findings of these excavations are recorded in Garth's final reports, [4] the excavations exposed the mission building foundations revealing building materials and methods of support, [5] and in many cases verified eye-witness descriptions of the site. [6] In addition, Garth uncovered evidence of the site's occupation by the Oregon Volunteers in 1848, adding to understanding of this post-mission period. [7]

The archeological excavations precipitated the completion of much needed research on Whitman Mission's appearance. In 1938, Regional Supervisor of Historic Sites Hagen emphasized "it is important that any excavation be preceded by exhaustive research on the location and description of all later buildings erected on the site as well as those of the early mission." [8] Thus, due to the impending excavation, the research void was quickly filled. George Tays of the Historic Sites Project-Whitman Mission's first historian--wrote a study on the mission site's appearance, and "The Whitman Mission Gristmills" was authored by William H. Gardner with notes by Hagen. In 1941, Archeologist Garth finished his study of Pacific Northwest architecture, which placed the Whitman Mission in the perspective of architecture during that time.

The effects of this research on the excavation were immediate. In reference to Garth's 1948 "Preliminary Report on Excavations in the Ruins of the Whitman Mission," Hillory A. Tolson, Acting Director of the National Park Service, remarked: "The report is noteworthy for the excellent way in which the historical data is integrated with the archeological evidence found in the ground." [9]

Chief Historian Herbert E. Kahler acknowledged Garth's 1949 work, "A Report on the Second Season's Excavations at Waiilatpu": "This report admirably illustrates the usefulness in employing archeological research methods to aid and supplement historical research methods." [10]

Finally, in response to "The Mansion House, Gristmill and Blacksmith Shop at the Whitman Mission, A Final Report," Chief Historian Kahler remarked, "We believe this to be a most important document, contributing much to our knowledge of the Whitman Mission structures." [11] Thus, research completed from 1940-1947 contributed to a more accurate interpretation of the archeological ruins.

The 1941-1950 excavation was the first attempt to verify historical information about the Whitman Mission. Combined with historical research, the excavations provided the basis for cultural resource management of the mission site from 1952-1962. The building sites were outlined and conjectural drawings were posted based on the evidence discovered by Archeologist Garth. As a result, the blacksmith shop was interpreted as a wooden, semicircular building until additional research proved this description incorrect. After Garth uncovered well-preserved adobe walls of the first house, they were displayed as an important cultural resource from 1954-1978. Although additional information gleaned from the 1960 excavations further improved cultural resource management, the first guide was and still is the excavation of 1941-1950.

|

|

Excavation of Blacksmith's Shop, supervised by Paul Schumacher, proceeds in 1960.> |

Archeology: 1960-1961

The second and final excavation at Whitman Mission National Historic Site, the 1960-1961 dig, solved a few more of the mission's mysteries and further improved the park's cultural resource management. The goals: discover the blacksmith shop and the grave of Alice Clarissa Whitman--the Whitmans' only daughter.

In 1959, the blacksmith shop excavation was added to the Mission 66 development projects. Superintendent Kennedy justified the exploratory work:

Recent information indicates that what is presently marked as the site, together with size and shape, of the Whitman Blacksmith Shop, is very likely not accurate inasmuch as the descriptions found are at variance with those now portrayed. It is desireable to carry out new archeological exploratory work to establish the facts about the blacksmith shop and thus assure that its interpretation has a foundation in fact. [12]

More simply put, Tom Garth's interpretation of a wooden blacksmith shop was proved incorrect after the 1954 discovery of William H. Gray's 1842 description of its adobe construction. [13] In light of this new discovery, further excavations were necessary to determine the building's location and dimensions. Any attempt to reconstruct the mission buildings would depend on accurate information.

Evidence for locating the blacksmith shop looked promising after Regional Archeologist Paul J. F. Schumacher excavated in October 1960. [14] Encouraged by the first dig, another search for the blacksmith shop proceeded from July-August 1961. [15] Although the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin reported in August 1961 that, "Archeologists have unearthed several pieces of material . . . that they believe is the remains of the blacksmith shop," [16] Erwin Thompson's 1973 "Feasibility Study on Historic Reconstruction" concluded that Schumacher "failed to locate any definite outline of the structure." [17] Despite this lack of conclusive evidence, Schumacher's excavation revealed enough information to at least warrant replacing the blacksmith shop's semicircular outline with a square outline. The 1962 "Annual Report on Information and Interpretive Services" reported that "the marker for the shop points out that the exact location of the building has not yet been determined." [18] Later this qualifier was dropped and the site simply interpreted as the blacksmith shop. As a result, the method of marking the shop's approximate location with concrete blocks continues today.

A search for Alice Clarrisa Whitman's grave was conducted at the same time. Superintendent Kennedy explained the need for this project in 1959:

Research has indicated that it may well be in one of two locations, both of which are situated in places which may be occupied by roads or trails in the proposed development of the Monument. In order to locate the remains so that they may be safeguarded . . . and properly marked, the explorations are necessary. [19]

Although the impending road and trail construction facilitated the excavation, interest in locating Alice Clarissa's grave existed long before 1959. Tom Garth reportedly discovered a child's grave in 1948 but could not prove it was Alice Clarissa's. [20] In 1953, a member of the Whitman family requested a marker in her memory. [21] Whitman Mission Historian Jack Farr concluded in 1958 that historical references to the grave indicated its probable location either north of the mission house near the old county road, area "from the fence separating the Monument property and the Frazier to the road on the west side of Shaft Hill about fifty yards southeast of the Great Grave." [22] When the October 1960 excavation failed to find the grave in the vicinity marked for construction, the road project proceeded without further delay. While Archeologist Schumacher did not find where the grave was, at least he determined where it was not.

Schumacher made one final effort to locate the grave in 1961. Acting under the assumption that the mission cemetery was near the base of Shaft Hill, Schumacher excavated along the base of the hill, near the Great Grave. [23] Schumacher hoped that the discovery of a skeleton within a coffin "about half way to the Great Grave from the entry road into the Monument" [24] would indicate the location of the child's grave. However, the skeleton--that of an Indian--helped locate the Indian burial grounds rather than Alice Clarissa's remains. [25]

In spite of the failure to locate the child's grave, in 1966 Mrs. Goldie Rehberg, honorary member of the Board of Trustees, Marcus Whitman Foundation, initiated a project to erect a marker to Alice Clarissa Whitman. [26] The movement gained widespread community support, so in 1966 and 1967 Schumacher returned to the mission to discuss the location for a marker in her memory. [27] On May 8, 1968, the Marcus Whitman Foundation dedicated a marker to the Whitman's only daughter [28] near the location of Schumacher's 1961 discovery of the Indian grave--approximately half way between the Great Grave and the Park's east entrance. Later that year, Park Ranger Larry Dodd discovered a letter-to-the-editor written in 1888 by massacre survivor Matilda Sager. The letter places the location of Alice Clarissa's grave next to the common burial site "where the parents and their only child would lie side by side . . . " [29] Superintendent Stickler said that the location revealed in this letter would be marked, [30] although it never was. Regional Archeologist Schumacher said that the 1888 letter:

Certainly supports my contention that they would have buried the massacre victims near the already existing Mission cemetery and therefore, Alice Clarissa's grave is in the hillside at the base of the slope, more or less where Superintendent Stickler and I marked it. [31]

In fact, if Matilda Sager's description is accurate, then Alice Clarissa's grave is probably closer to the Great Grave than marked. [32] Superintendent Amdor wrote in the 1982 "Resource Management Plan" that, "it remains questionable if the spot along the west end of the Shaft Hill is the most fitting for such a marker." [33] Nevertheless, the archeological excavations gave Superintendent Stickler and Regional Archeologist Schumacher some indication of where the grave might logically have been as well as revealing where it was not. Management has not found it necessary to move the stone, so the Alice Clarissa Memorial remains today as it did in 1968.

While the 1960-1961 excavations did not provide as much new information as hoped, they provided enough information for administrators to proceed with some very important cultural resource decisions. Superintendent Kennedy approved the new blacksmith shop markings, and Superintendent Stickler approved Alice Clarissa's grave marker. In addition, Schumacher's brief excavation of the Oregon Trail and Whitman's original irrigation ditch in 1961 assured their restoration: the irrigation ditch in 1961 and the Oregon Trail in 1963. The location of the park's new approach road and trails also depended on the archeological finds, as did the reconstruction issue. Further, Historian Erwin Thompson researched the blacksmith shop history and the graves at Waiilatpu in order to assist Schumacher's work, just as preliminary research of the mission buildings helped Tom Garth. The excavations of 1960-1961 stimulated research, cultural resource management, and interpretation and ultimately contributed to a more accurate representation of the Whitmans' mission.

Reconstruction

One of the most controversial cultural resource issues ever debated at Whitman Mission National Historic Site centered on reconstructing the mission buildings. Ever since 1935, when the Whitman Centennial, Inc., first requested "the restoration and reconstruction of the Waiilatpu Mission," [34] superintendents have confronted this issue. Oftentimes, they sought assistance from the Regional Office in order to answer visitor inquiries about the status of reconstruction. In fact, Superintendent Stickler's request for information caused Regional Historian John A. Hussey to write a brief reconstruction chronology in 1965. This chronology provides the basis for much of the following information. In many ways the 1973 decision to forego reconstruction affected the park's entire program--interpretive, maintenance, and administrative. Therefore, an examination of this important cultural resource issue follows.

From the first, mention of reconstruction evoked hesitancy from National Park Service personnel. In 1936, Olaf T. Hagen, Chief of the Western Division Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings, recommended delaying reconstruction until after archeological excavations; the next year Regional Historian Russell C. Ewing agreed. [35] Basically, the National Park Service preferred a "wait and see" approach rather than immediate action.

In contrast, most Walla Walla residents including Whitman Centennial, Inc. President Herbert West advocated restoration. In response, National Park Service representatives maintained that archeological excavations were top priority and had to precede reconstruction. Hagen explained this position to T. C. Elliott of Walla Walla: "It was stated that no restoration be made unless further research and archeological excavations revealed adequate information for reasonably authentic replicas of the original buildings." [36]

Supervisor of Historic Sites Ronald F. Lee firmly established the basis for this position in 1939:

Should questions of restoration policy become involved in the consideration of monument problems I would suggest that they may be studied in light of the policy outlined in the Director's memorandum of May 19, 1937. [37]

The policy to which Mr. Lee referred included several points pertinent to Whitman Mission, including "Better preserve than repair, better repair than restore, better restore than construct." [38] Further, Director Cammerer left no doubt about the course to take at Whitman Mission: "No final decision should be taken as to a course of action before reasonable efforts to exhaust the archeological and documentary evidence as to the form and successive transformation of the monument." [39] Thus, even before the park was established in 1940, regional administrators decided that the future of reconstruction would be based upon the historical restoration policy adopted by Director Arno B. Cammerer on May 19, 1937. [40] These policies (with very slight modifications) [41] were still in effect in 1965. From 1941-1950, then, the fate of reconstruction depended upon the results of Tom Garth's excavations. More importantly for public relations, during these nine years of intermittent archeological digs, National Park Service personnel could truthfully "continue to plead lack of knowledge when pressed to initiate restoration." [42]

On the other hand, some National Park Service officials thought the possibility of reconstruction slim, at best, no matter what the excavations revealed. Supervisor of Historic Sites Ronald F. Lee reiterated to Herbert West that the Service "must remain uncommitted until the archeological work has been completed," but cautioned that excavations alone would probably not justify reconstruction: "The determining factors are several, including educational, aesthetic, and scientific considerations." [43] Therefore, prior to 1950, "the reluctance of the Service to embark on reconstruction was based on policy." [44] However, because this policy left open the possibility of reconstruction, various arguments, both pro and con, continued to surface.

Many people were caught up in the reconstruction debate. Mount Rainier Superintendent Preston Macy clearly favored reconstruction, telling Regional Director Tomlinson, ". . . We should begin now to plan on a complete reconstruction of the Whitman area. I can conceive of no finer project." [45] In fact, Macy suggested including reconstructed furnishings in the reconstructed buildings. [46]

Ernst A. Davidson, Regional Chief of Planning, did not share Preston's enthusiasm because, in his words:

There are still grave doubts in the minds of some historians and others of the Park Service as to the wisdom of attempting actual restorations. In lieu of this we have also thought of merely outlining the foundations when and if discovered . . . leaving the super structures to the imagination of visitors assisted by a model in the Museum . . . . [47]

One of the strongest advocates of this mission model idea was Regional Supervisor of Historic Sites Aubrey Neasham who, as early as 1942, doubted that sufficient details of the original buildings would ever be located to warrant reconstruction. [48] Dr. Neasham's arguments were reported in the Union-Bulletin in 1946:

Dr. Neasham declared that he did not believe in restoration of or building a replica of the mission. He explained that many times the replicas of buildings are found to be historically incorrect later.

"The problem of maintenance is also to be considered," he said . . . . His idea was to expose the foundations of structures if possible. Then to tell the story of the Whitman people with scale models of the mission in a museum. He felt that . . . seeing the ruins of the mission would be even better than seeing replicas of buildings. With this method, he stated, there would be little that is artificial and the grounds would serve as a retreat and the atmosphere preserved. [49]

Dr. Neasham's campaign against reconstruction convinced West and other influential Walla Wallans that a mission model and museum were preferable to reconstruction. [50]

While Dr. Neasham was busy convincing locals to favor museum exhibits, he was convincing National Park Service personnel, as well. In 1947, three years before the excavations were completed, the master plan was revised and included no reference to reconstruction. The reasons for this change were reported in the Union-Bulletin:

There would be no actual reproductions of the mission buildings on their original sites as had been proposed previously. The present trend in historic sites is against such reproductions it was explained by Dr. Aubrey Neasham . . . "It has been found more desirable to preserve such sacred areas in their present conditions than to trespass and build, reproductions which obviously are only that . . . ." [51]

In effect, by 1947 the predominant view was that, regardless of archeological evidence, the site could be better interpreted by models than by obvious reconstructions. Or, as explained by Regional Historian Hussey in his reconstruction chronology: "The burden of [Neasham's] plea, I think, was that the actual sites themselves, properly interpreted, had more impact and more educational value than would any restoration, no matter how accurate." [52]

Dr. Neasham's arguments remained persuasive for years, gaining more credibility when Garth's excavations did not reveal enough information to completely verify the mission's appearance. Accordingly, then, the building sites were outlined with timbers in 1952 and a museum planned to include models of the mission buildings.

While Dr. Neasham's argument quieted the reconstruction controversy somewhat during the early 1950s, the issue never entirely disappeared due, in part, to the park's long drawn-out development plans. During the 1950s the National Park Service sought land and money for development of a superintendent's residence, museum-administration building, and utilities. This obvious emphasis on modern facilities struck many Walla Wallans, already upset about the monument's slow development, as an inappropriate priority. This widely-held view is reflected in a 1952 letter from Walla Wallan Betty Richardson to Assistant Regional Director Sanford Hill, in which she disagrees with plans "to erect an ordinary building at the mission site instead of making 'copies' of the buildings that were burned during the massacre." [53] Hill's response is one of the best indicators of the National Park Service's attitude in the early 1950s regarding Whitman Mission's reconstruction:

Should we place the handiwork of our own generation on [the mission site] we will have created an illusion which, though interesting, is not of the Mission period. Through the preservation and presentation . . . of the authentic building foundations where possible, we have felt that the visitor would grasp the spiritual significance of the area, and perhaps would be able to create in his own mind a sense of historical reality which would not be possible in a full restoration . . .

[The Whitman National Monument] is in the main a memorial dedicated to the memory of the courageous missionaries who founded the Mission. Being hallowed ground, therefore, it should not be disturbed by the buildings of this generation, regardless of how far they might go to recreate the original picture. [54]

Essentially, Hill reworded Dr. Neasham's earlier argument that reconstruction would only intrude on the historic scene.

The reconstruction issue continued to be closely tied with the mission development plans throughout the late 1950s. With the legislative authority to acquire additional land secured in 1958, the park's master plan required revisions in order to reflect the latest construction proposals. Therefore, arguments against reconstruction fell under fresh scrutiny. After Regional Chief of Interpretation Bennett T. Gale raised the issue in Washington, D. C., "The consensus was that the question of restoration be considered for Whitman National Monument . . . . " [55] Therefore, upon the request of Regional Director Merriam, Superintendent Kennedy presented his recommendations in favor of reconstruction. Thus, the debate started all over again in 1958.

Superintendent Kennedy cited several reasons for supporting reconstruction, the most important of which was the need for proper interpretation: The "present bare site [outlined with concrete blocks] does not provide a framework to guide the imaginations of people . . . ." [56] Kennedy also cited the great demand for restoration and finally concluded that sufficient evidence existed on which to base reconstructions. [57] He criticized the arguments against reconstruction, stating that monument employees had "carefully tried to discourage it in order to avoid embarrassment to the staffs of the Director and Regional Director." [58] However, Kennedy acknowledged the need for complete historical evidence and concluded: "If a restoration were to be carried out, it would be advisable to assign to an historian the project of bringing together all the significant material on each of the features to be restored." [59]

After reviewing Kennedy's recommendations, Regional Director Merriam agreed that further historical research should precede reconstruction; therefore, he recommended that action be deferred until after Mission 66 developments were completed. He concluded:

We should like to have the experience of interpreting the monument through the use of a model of the site and other exhibit devices in the proposed visitor center before a decision is reached on the question of restoration. The visitor center displays and the restoration of the grounds so as to be more in keeping with the appearance at the time of occupancy would, in our opinion, form the basis of an easily understandable story and present a significant and attractive scene to the visitor. If later restoration of structures appears desirable, we will have lost nothing, for the visitor center would, of course, be continued as an introduction to the site. [60]

Acting National Park Service Director Eivind T. Scoyen concurred by stating that reconstruction would be reconsidered after full analysis of the historical sources by a historian. [61] Thus, the Mission 66 development projects progressed as scheduled with the museum as the primary interpretive device. However, from 1958 onward, currents ran more strongly in favor of reconstruction than in previous years. The predominant argument shifted away from a concern for the historic scene to a concern about historically accurate reproductions.

This new open-mindedness regarding reconstruction was reflected in several park documents. For example, the 1960 master plan cautioned:

Do not close the door on restoration of the mission and of its various features. Continue to pursue research to reveal the details of the construction or appearance of the mission buildings and other facilities. [62]

Superintendent Kennedy also wrote a "Prospectus for Restoration of the Whitman Mission" in October 1960, in which he stated that he believed research would produce reconstructions that were 95 percent accurate. [63] However, research that same month revealed that such accuracy was highly improbable.

Excavations conducted by Regional Archeologist Paul Schumacher in October 1960 failed to reveal any evidence of the blacksmith shop. Superintendent Kennedy reported in the October "Monthly Narrative Report" that the building's exact location was apparently not determined. [64] Additional research central to the reconstruction issue was conducted by Historian Erwin Thompson. His study on the appearance of the Mission House Kitchen (1961) and "Report of the Appearance of Waiilatpu Mission in 1847" (1962) revealed that gaps existed in the available information about the appearance of the mission. The fervor for reconstruction slowly dissipated because of Thompson's report and the inconclusive blacksmith shop excavations. Thus, the concrete outlines of the building sites were supplemented with individual room outlines in May 1961, [65] and audio stations were installed at the mission sites in August 1963. [66] After September 1963, the visitor center and museum oriented visitors to the Whitman story and the mission site. Finally, in 1965, Regional Director Edward Hummel suggested deleting reconstruction from the park's master plan. [67]

When it appeared that Whitman Mission administrators had heard the last of the reconstruction issue, it surfaced one more time in 1970, when:

Mrs. Julia Butler Hansen, Chairman of the House Subcommittee on Appropriations, during the course of the Hearings of the National Park Service 1971 fiscal year budget, on March 18-19, asked Director George B. Hartzog if the National Park Service had considered reconstructing the buildings at Whitman Mission . . . . Director Hartzog said that the Service had not recently considered the question, but that he would have it studied. [68]

The result was "A Feasibility Study on Historic Reconstruction" by Erwin Thompson of the Denver Service Center Historic Preservation Team, formerly from Whitman Mission. This 1973 study determined that reconstructed buildings would not necessarily increase understanding of the Whitman story and they would not necessarily be accurate: "The archeological, historical, and architectural data do not exist for anything but a conjectural reconstruction of the mission house, blacksmith shop, emigrant house, and gristmill." [69]

In addition, the exact location of the blacksmith shop was never found. Therefore, due to lack of historical evidence necessary to comply with "administration policies of the National Park Service affecting reconstruction at historical areas," [70] Thompson recommended the Whitman Mission sites should not be reconstructed. Interestingly, Mr. Thompson, himself, had a change of heart over this issue. During his three years as Whitman Mission's historian, Thompson favored reconstruction. Then, several years later, an important discovery changed his mind:

. . . after the Kane sketch [of the Whitman Mission] was discovered . . . I suddenly realized that reconstruction was not a very good idea. If we had gone ahead with the evidence we had before Kane we would have wasted Federal monies. [71]

As it turned out, Mr. Thompson's report effectively concluded a debate that lasted nearly forty years.

This decision is the most important cultural resource development to affect the Whitman Mission National Historic Site. The decision to not reconstruct preserved the tranquil setting that is important to the park's memorial nature. Very likely, reconstruction would have shifted interpretive focus to the reconstructed buildings rather than on imagining times past. Maintenance would have increased and the administration would have had to grapple with making these modern developments seem historic. In short, reconstruction would have resulted in an entirely different national historic site. Therefore, recognition is given to all those who debated the reconstruction issue, both pro: Whitman Centennial, Inc., President Herbert West, Mount Rainier Superintendent John Preston and, more recently, Superintendent Joe Kennedy, and the con: both Regional Supervisors of Historic Sites, Olaf T. Hagen and Aubrey Neasham, and Historian Erwin Thompson. Only after the surfacing of all sides of the issue and re-evaluation of policies could such a far-reaching decision be made.

The Great Grave

The two-ton marble Great Grave slab laid in 1897 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Whitman massacre was one of the first cultural resources to concern National Park Service management. Just as the original grave of the massacre victims suffered from neglect, the Great Grave suffered a similar fate from time to time. Until 1962 a road led to the Great Grave from the park's east entrance and continued beyond to the neighboring farm. A parking area surrounded the grave as did a decorative iron fence. Cars turning around in the parking area would hit and damage this railing and Superintendent Weldon remembers that parties near the grave caused several complaints. [72] As a result, one of the notable accomplishments of 1952 was the clean up of "this hitherto somewhat weedy area" [73] and repairing the car-damaged railing that surrounded the grave. In 1962, as part of the Mission 66 development project, this road was converted to a trail and the surrounding parking area eliminated, [74] creating a more peaceful atmosphere in which to view the grave.

A proposal to change the Great Grave's appearance arose in 1950 and remained a possibility for years. Mr. W. D. Church requested permission from the National Park Service to add the first name "Walter" to the last name "Marsh" which was carved on the slab in 1897. [75] Regional Director Merriam approved the request provided the family paid the recarving expenses. [76] Although the project was abandoned in 1952 when the family failed to find a company able to carve the stone, [77] Superintendent Weldon agreed with Church that all the names should be recarved: "I told him this seemed to me a good idea and if the local people didn't get it accomplished I thought we ought to set it up as a Park Service project one of these days." [78] Indeed, this almost became a Park Service project in 1973 when Historian Erwin Thompson recommended recarving the 14 names on the marble slab to correct misspellings, to improve their visibility, and to remove the name of one person who did not die in the massacre. [79] The stone was not recarved, however, because of a later suggestion by Dr. Norman Weiss of Columbia University, an expert in the conservation of masonry structures. [80] The 1984 "Resource Management Plan" reported that "Dr. Weiss recommended polishing the raised letters, not only to improve its readability, but also to preserve the marble from accelerated weathering." [81] Superintendent Amdor agreed with the recommendation stating, "We're not going to change history. If [the names are] wrong its really a function, then, of interpretation to interpret that its wrong, not a function of management to fix mistakes to make it acceptable." [82] Therefore, polishing the stone remains the preferred method for preserving these inscriptions.

Dr. Weiss's principal contribution to long-term grave management was his recommendation for stabilizing the marble slab which was cracking due to sagging of the stone's center. Weiss stated, "There is no easy way to solve this problem without partial (or complete) dismantling." [83] Therefore, the goal was to install additional support for the center of the slab which would alleviate the stress and halt cracking. [84] Under the supervision of Regional Archeologist James Thomson and Regional Historical Architect Laurin Huffman, the contractors--Alderwood Contracting of Lynnwood--completed the rehabilitation on November 15, 1983. [85] With the slab on a secure foundation, cracking due to settling and warping will stop, although cracks may expand from frost. [86] Management of the grave now consists of annually monitoring the cracks and warps and comparing measurements from year to year. [87] Superintendent Amdor called the Great Grave rehabilitation "The most long-term cultural resource project we've done." [88]

Memorial Shaft

The Memorial Shaft, erected one month after the 50th anniversary of the Whitman massacre, commemorated the Whitmans long before a national park was established in their name in 1940. The shaft and the Great Grave were the only markers of the mission's existence until archeological excavations were undertaken in 1941. Bob Weldon was the first administrator to actively manage and try to beautify the shaft area. Not only was the grave's appearance improved during Superintendent Weldon's administration but for the first time water was pumped to Shaft Hill to provide green grass around the memorial shaft. [89] The same road that led to the Great Grave led to the shaft, although it was a steep climb for cars. In 1952 the road was converted to a path with a gate at the bottom to prevent cars from driving up the hill. [90] During this time, the land on the hill surrounding the shaft was farmed by neighbor Enos Miller. Given that Miller's only access to the hill was up this trail, Superintendent Weldon often found the freshly smoothed and manicured path torn up by farm machinery. [91] This problem was alleviated when Miller moved in 1953. [92]

Another long-term management concern included determining the proper nomenclature for the shaft. In 1952, Assistant Director Ronald F. Lee recommended the marker be designated as the "Whitman Memorial Shaft" [93] to distinguish it from the park which was called the Whitman National Monument. However, until 1963 when the park's name was changed from national monument to national historic site, visitors confused the memorial shaft with the entire park, oftentimes never stopping at the mission site itself. The 1963 name changed solved this misunderstanding.

In 1982 there was concern that the shaft was tilting. The 1982 "Resource Management Plan" noted that:

One corner of the Memorial shaft is slightly lower than it should be, due, apparently, to excessive irrigation of the lawn around it. A lateral crack has appeared at the point in which the shaft rests on the base on the Memorial. The crack appears to be the result of the slight sagging of the corner of the Memorial. [94]

Corrective action included reducing irrigation and monitoring the degree of sagging. In 1985, upon the suggestion of Regional Historical Architect Huffman, the shaft was cleaned, the sprinkler heads moved to spray away from the base and fixed measuring points established to monitor movement of the shaft. [95] If measured annually, any movement in the shaft will be detected and further action taken, although after examining the memorial's concrete foundation, Superintendent Amdor said there was "no way" [96] the memorial could move. Confirming this suspicion, a survey conducted by Anderson Perry and Associates in 1986 failed to detect any significant movement of the shaft [97] since 1985. This periodic monitoring should prevent any problems before they occur and should ensure effective management of the shaft in the future.

The Mission Site

The park's most important cultural resource is, of course, the mission site where Marcus and Narcissa Whitman established their mission and lived for eleven years. From the once busy center of farming, teaching, and ministering to the serene park-like setting of today, this site has changed drastically and is administration's primary cultural resource. Excavated from 1941-1950, the site came under the responsibility of Superintendent Weldon from 1950-1956. During his administration, the sites were backfilled, covered with gravel, and outlined with timbers. [98] This method of delineating the mission buildings sufficed until 1957 when Superintendent Kennedy replaced the planks with concrete blocks. [99] Upon Director Wirth's suggestion, the room interiors were outlined in 1961. [100]

From 1952 onward, the mission site was managed as a self-guiding site. Begun initially to provide visitors with information when Superintendent Weldon was absent, [101] the self-guiding trail and sign program became an important part of cultural resource management. The first signs were located at the gristmill, first house, emigrant house, and blacksmith shop with bulletins placed near the millpond, great grave, and memorial shaft. [102] In 1953, five new signs arrived for the memorial shaft, great grave, millpond dikes, mission agriculture, and the mission children. [103] A sign also marked the Whitman-Eells memorial church site for a short time. [104]

In 1960, Park Historian Thompson suggested revising the trail system to encourage visitors to end their tour of the grounds at the mission house where the massacre occurred--the climax of the Whitman story. [105] His suggestion was incorporated into the 1962 revised master plan and the trail completed in May 1962. [106] The next year Thompson and Superintendent Kennedy planned a new comprehensive interpretive sign program consisting of metal photo signs and audio stations, which proved popular with visitors and eased the burden on the interpreters during those busy development years. [107] In 1978, the old signs were replaced with a new series--eleven wayside exhibits, one moveable exhibit on the Oregon Trail, and three directional markers. [108] These exhibits, at the park today, include audio stations at the gristmill, emigrant house, blacksmith shop, and mission house, on the spot where Alice Clarissa drowned, and at the Great Grave and the Memorial Shaft. Thus, the self-guiding trail continues to meet both management and visitor needs.

|

| The First House wall display. |

Although the mission buildings were never reconstructed, a portion of the adobe-brick wall of Whitman's first house was displayed in situ from 1954-1978. Then, after 24 years of the wall's deterioration, management decided that the best way to manage this valuable cultural resource was to cover up the display. This was long delayed, yet not surprising, decision considering that the adobe exhibit was problematic from the beginning. Housed in a concrete box with a glass top for viewing, Superintendent Kennedy reported only two years after its installment that sloughing of a portion of the wall had occurred due to minus 20 degree weather. [109] Given that such cold weather would likely reoccur, Kennedy wondered then just how permanent this exhibit would be. [110] Nevertheless, a heat lamp and fan were installed to protect the adobe from the cold weather, [111] although standing water and excessive condensation inside the glass were continual problems. [112] In March 1967, upon the suggestion of Paul Schumacher, Chief, Archeological Research, a sealant called Pencapsula was applied to the adobe and reapplied in November. In spite of this treatment several inspections revealed further cracking and sloughing of adobe. [113] A consultation with Mr. C. E. Holmes, who was familiar with Pencapsula, revealed that the Pencapsula itself probably contributed to the deterioration. [114] In 1967, Regional Curator Edward Jahns requested assistance from Don P. Morris of the Ruins Stabilization Unit, Southwest Archeological Center, who recommended two alternatives -- either sealing the wall portions under grade level or burying the wall and constructing a replica. [115] Regional Curator Jahns had doubts about both options, as did Superintendent Stickler and Regional Historian John A. Hussey. [116] As a result, Superintendent Stickler stated the course of action that was ultimately followed, "Another alternative is to display the present exposed section of the wall as long as it is presentable." [117] In other words, the wall was displayed regardless of deterioration. By 1976, the Wayside Exhibit Plan indicated that the display would be dismantled: "The new [first house] exhibit will not expose any portion of the adobe wall." [118] The adobe wall exhibit was finally backfilled to prevent further deterioration in 1978. [119] Thus, after years of trying to stabilize the adobe, management determined the best way to ensure the existence of this important cultural resource was to return it to earth which had previously protected it so well.

The Oregon Trail

From Independence, Missouri, to Oregon City, Oregon, the Oregon Trail represents pioneers and westward expansion. From 1836-1847 the Whitman Mission was a station on this trail, providing supplies and shelter for hundreds of emigrants traveling west. When the mission became a national park in 1940 the county road ran east-west across the park, in a location traditionally recognized as the Oregon Trail. Plans to reroute this road and reconstruct the trail were first formed in 1947, [120] although it was not accomplished until 1963. [121] A brief excavation of the supposed location in 1961 failed to reveal any archeological evidence of the trail, [122] although sketches of the mission made by eye-witnesses confirm its location.

Traditionally, the ruts were maintained with herbicides except for a brief period from 1980-1984 when hand tools were used. [123] In 1985, a gasoline powered line marker was purchased to remove any vegetation from the ruts. [124] Active management of the Oregon Trail will continue in the future, due, in part, to its inclusion on the List of Classified Structures in 1985 along with the Great Grave and Memorial Shaft. Additional classified structures at the park include the millpond, irrigation ditch, and the Walla Walla River oxbow.

Millpond, Irrigation Ditch, Oxbow, and Orchard

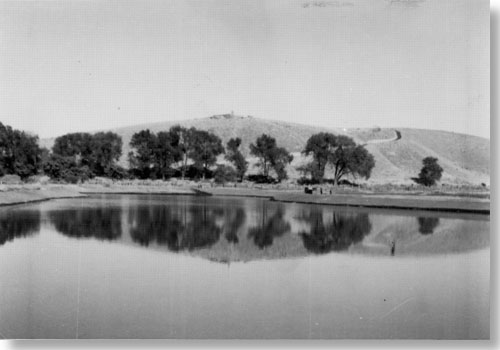

Whitman's millpond, originally used for irrigation and for the gristmill, was restored in 1961. [125] However, because of erosion caused by the Canada geese, mallard ducks, muskrats, moles and gophers, the dike was rebuilt in 1981 and again in 1982. [126] The millpond is currently managed under the cultural cyclic maintenance program.

|

| The millpond as it appeared after 1961. |

The irrigation ditch is just as important today as it was when Marcus Whitman irrigated his crops 150 years ago. A section of the irrigation ditch was restored in 1961--moved from the north side of the Oregon Trail to the south. [127] As a result, the ditch is preserved and interpreted as part of the mission story, while carrying water for modern agricultural purposes, as well. [128]

While the Whitmans were at Waiilatpu, the Walla Walla River ran immediately south of their first house. It was in this river that their daughter, Alice Clarissa, drowned in 1839. Today the dry channel is visible as it bends sharply south of the first house site. Signs have marked this oxbow since 1953; the 1984 "Resource Management Plan" recommended controlling the weeds and brush with fire to further define the oxbow. [129] As a result, mowing is the current method of managing this cultural resource.

The apple orchard first planted by Superintendent Weldon to resemble the Whitmans' orchard has been maintained since 1955 with "old fashioned" apples that were available in the 1840s. Superintendent Weldon planted Northern Spy, Spizenberg, Winesap, and Baldwin varieties. [130] Today the orchard is a small cluster of trees maintained to give visitors a sense of the Whitmans' orchard.

Pioneer Cemetery and Indian Burial Ground

Management of Alice Clarissa's grave marker is discussed under the archeology section of this chapter. The pioneer cemetery is located east of the Great Grave, although only a few grave markers survived. Photographs as early as 1897 reveal two small headstones marking the graves of two early pioneer families--the Stones and McElhaneys. In 1958, Superintendent Kennedy removed these markers because they were repeatedly vandalized and in his words, "did not contribute importantly to the Whitman story." [131] In 1960, Mrs. Leslie R. Keays requested that the markers be returned to the cemetery so the assistant regional director suggested placing markers that were flush with the ground. [132] He also suggested to Director Wirth that "some sort of interpretive marker explaining the history of the entire pioneer cemetery is in order . . . . " [133] In 1960 two markers were placed flush with the ground to commemorate both pioneer families, and a wayside marker for the cemetery was established in 1986. [134]

Located at the base of Shaft Hill, a small portion of the Indian burial ground was excavated by Schumacher in 1961 [135] but, like the pioneer cemetery, was not marked. In 1978, the Native American Religious Freedom Act required re-evaluation of such policies, so marking the site was reconsidered. After consulting with elders of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, it became clear that the descendants of this culture preferred that the status quo continue. [136] Therefore, management has no plans to mark the site at present.

Artifact Preservation

After excavation in the 1940s, the park's artifacts required special care, yet they did not always receive the attention necessary for proper collections management. For years the artifacts were kept in the temporary storage shed-museum in small drawers "where the iron would rust and turn into dust," said Historian Thompson. [137] The National Park Service was slow to preserve many of the park's small metal artifacts and as a result, lost many through deterioration. Faced with the need to select artifacts for the new museum and to help Regional Archeologist Paul Schumacher identify the metal artifacts discovered in the 1960 excavation, Superintendent Kennedy addressed this heretofore ignored issue. [138] In 1961, because of Archeologist Schumacher's insistence, iron artifacts from the blacksmith shop were sent to the Eastern Museum Laboratory in Washington, D. C., for long overdue preservation treatment. [139]

Lack of proper artifact storage space was another perpetual problem. Because of the limited storage in the temporary museum, the Walla Walla Chamber of Commerce offered space in their basement during Kennedy's administration. Then, in 1964, the artifacts were transferred to the new visitor center. However, this building also lacked proper space. The collections were divided between a small storage room in the corner of the maintenance garage and a corner of the visitor center office area. [140] This inadequate situation was remedied in 1984 with the completion of the artifact storage room, effectively solving a problem that has lasted 34 years.

Once proper storage space was secured, the next step in managing the collection was recataloging the artifacts, originally catalogued during the late 1960s by Park Historian Robert Olson some 20 years after the excavations. To meet this need David T. Wright and Associates prepared the park's "Collections Management Plan" in 1986 which currently guides management of these cultural resources. Cataloging the park's historic photographs is only one of the many recommendations being implemented. A workplan developed in 1987 outlines specific goals for the next five years including use of the National Park Service computerized cataloging system. [141] Quicker access to information is just one of the benefits of this system. Roger Trick, Chief of Interpretation and Resources Management, has stated that knowledge about the Whitmans could be increased:

What we have . . . is a time capsule [of the Whitman story] . . . but it's really kind of disappointing how few researchers have come to use the collection and that's because it really hasn't been very useable . . . . There's a few masters theses and probably a couple of doctoral dissertations sitting in the artifact room [waiting to be written]. [142]

This data-entry project rivals any previous cataloging effort for complexity. Once completed, it will effectively bring Whitman Mission's artifact storage and access system out of a history of neglect and into a future of accessibility.

The long-needed but long-delayed attention to the park's artifacts reflects management's new awareness of this important cultural resource. The same concern is being shown to the natural resources which also received little attention in the past.

NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Sensitive management of the park's natural resources is vital to preservation of the historic scene. Yet, a management strategy to protect these resources has only recently been developed. The 1982 "Resource Management Plan" acknowledged the need for increased emphasis on the park's natural resources and, as a result, established a schedule for air and water monitoring, hazardous tree removal, grazing, and vegetation studies. [143]

An important result of this new awareness is the current revegetation project. In 1984, Landscape Architect Cathy Gilbert completed the "Landscape Study and Management Alternatives for Revegetation," which outlines specific steps for managing the park's natural resources and preserving the historic scene. The "Landscape Study" acknowledges the difficulty in reestablishing the native vegetation because of the greatly modified landscape, yet concurs with the goal stated in the park's "Statement for Management": "To maintain as nearly as possible, the visible aspect of the historic period commemorated." [144] Therefore, the "Landscape Study" divides the park into six separate land units recommending different revegetation options for each unit. As a follow-up study, Jim Romo and William Krueger of the Cooperative Park Studies Unit at Oregon State University completed the "Weed Control and Revegetation Alternatives for Whitman Mission National Historic Site" in 1985. This study subdivided Gilbert's six units into fifteen areas and prescribed specific revegetation instructions and timelines for each area, including prescribed burns, herbicides, and reseeding. However, park administrators were dissatisfied with the results so they turned, once again, to Oregon State University for advice. Superintendent Herrera explained that their current consultant has a different theory about the best way to revegetate the park:

The agronomist from Oregon State University, Dr. Larry Larsen, told us last week . . . that when [you disturb ground by burning, plowing, and spraying herbicides] and then attempt to reseed it and hope that . . . you don't lose that reseeding due to competition, he says, you could be worse off than when you started . . . you could have a bumper crop of weeds the next year. [145]

Therefore, Dr. Larsen's plan entails planting grass varieties that are least competitive with the native species, and then once these varieties are established, plant the desired, native grasses. Superintendent Herrera is confident about Dr. Larsen's plan and predicts the project will last for 5-8 years. Chief Interpreter Trick anticipates that, at the end of that time, probably 75 of the park's 95 acres will be revegetated. Trick considers revegetation both a cultural and natural resource project because native growth will improve not just the park's appearance but interpretation, too. Superintendent Herrera agrees that revegetation will have a dramatic effect on interpretation:

If visitors in years to come can come here and can see some of the native tall grasses and other vegetation that was here 150 years ago, that you rarely see in this area any more, it would be quite an attraction . . . they will sense that there's something special about this place. [146]

Thus, revegetation is a program that will contribute to increased awareness of both natural and cultural resources and will help to ensure their care in the future.

Clearly, each superintendent was primarily responsible for the degree of protection given to the park's cultural and natural resources. However, the amount and quality of preservation that a resource received oftentimes depended upon the conservation treatments available at the time. Regardless of past neglect, today managers are attuned to their responsibility for both the cultural and natural resources and, as a result, high quality care can be expected to continue.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

whmi/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2000