|

White Sands

Dunes and Dreams: A History of White Sands National Monument Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER THREE:

NEW DEAL, NEW MONUMENT, NEW MEXICO 1933-1939

Advocates of White Sands National Monument secured President Hoover's proclamation not a moment too soon. Unlike other units of the park service, White Sands did not face imminent danger from resource developers. Instead, the presence of a federal agency in the Tularosa basin dedicated to the preservation of natural wonders offered access to public spending at the lowest ebb of the Great Depression. This sense of urgency would persist throughout the years of the Roosevelt "New Deal," affecting all aspects of park service planning, policy, and program development. In this manner, White Sands offered a window not only on the complexity of NPS operations, but also shed much-needed light on the little-known dimensions of 1930s southern New Mexico.

The historian Gerald D. Nash, author of the path breaking The American West in the Twentieth Century (1977), described the impact of the Depression and New Deal on the region as if he were speaking of White Sands itself. Whether one analyzed variables of economics, politics, environmentalism, or cultural change, the afflictions facing the West surrounded the dunes in equal measure. "Everywhere western dreams for sustained economic growth lay shattered," said Nash, "victims of the national economic collapse." Farm and ranch income, dependent upon eastern and international markets, fell by more than 50 percent. So did resource extraction, especially petroleum, a blow to the oil fields of southeastern New Mexico and west Texas where prices dropped from $2.50 per barrel in 1929 to ten cents per barrel four years later. More ominous for the new park service unit, however, was the regional decline of tourism (by more than one-half), the source of visitations that could generate future federal spending at the dunes. The New Mexican per capita income stood in 1933 at $209, or 52 percent of the national average. There would be little discretionary income for local residents, making White Sands' free admission small consolation. [1]

In essence, the monument evolved in the same style of experimentation and uncertainty that marked the policies of the Roosevelt administration. Richard Lowitt, author of The New Deal and the West (1984), wrote that "depression, drought, and dust undermined dependence on the marketplace as an arbiter of activities." In its place were a myriad of federal rules, regulations, and employment agencies that removed control of economic life from county courthouses and state capitols to Washington, DC. For New Mexico and its Tularosa basin, however, public funding offered the only source of investment for private enterprise. Thus it was that local and state officials would devote considerable attention to the growth of the monument, both helping and hindering park service personnel charged with preserving the dunes and catering to a multiplicity of public tastes. [2]

At the close of the New Deal decade, NPS officials would have high praise for the consequences of planning and implementation of service policy. Hugh Miller, superintendent of the "Southwestern National Monuments [SWNM]," reported in September 1940: "White Sands has demonstrated its unquestioned standing as the most important southwestern monument from the standpoint of visitor interest." Within two years of its opening, the monument eclipsed all attendance records for the 23-unit SWNM system that encompassed the "Four Corners" states of Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and southern Colorado. Yet no one connected to the park service could have prophesied the organizational debate that ensued in 1933 over the proper functions of the vast gypsum dunes. Some of this could be ascribed to the still-evolving corporate culture of the NPS, which along with other federal agencies had to learn hard lessons about western ecology, economics, and politics. It would not help, as Gerald Nash noted, that federal officials "often openly expressed contempt or hostility for western ways." Monument custodian Tom Charles, his contemporaries in Alamogordo, and the regional and national hierarchy in the park service thus spent seven years defining the standards that would guide White Sands for the remainder of the twentieth century. [3]

Within days of President Hoover's announcement, Tom Charles wrote to Horace Albright about the park service's strategy for assuming control of White Sands. Local civic boosters wished to celebrate their good fortune with a dedication ceremony that summer. Albright encouraged this as "a means of getting wide-spread publicity." The monument would come under the purview of NPS' s famed superintendent of southwestern monuments, Frank "Boss" Pinkley. Because Pinkley worked at the Casa Grande ruins south of Phoenix, Arizona, he doubted that he could travel to southern New Mexico before the spring of 1933. Albright further warned Charles that no congressional action on funding for White Sands could occur until that July. This did not stop Charles from seeking Pinkley's permission to take a highway grader out to the dunes to create an access road into the monument. Pinkley thus had to issue the first of many warnings to the exuberant Charles, asking him to wait until NPS personnel arrived to survey the new monument. [4]

Pinkley's word of caution bothered Charles not a bit, as he believed that the real power in the federal government resided in Congress, not in the park service. He soon wrote to White Sands' benefactor, Bronson Cutting, asking his help in bringing highway construction to the monument. He told New Mexico's senior senator of the "desperate straits" facing Otero County, and wondered if President Roosevelt's "reforestation program" could be stretched to include roads out of the Lincoln National Forest to the dunes. Because the matter involved a powerful senator (to whom FDR had offered the position of Interior secretary that winter), acting NPS director A.E. Demaray had to reply to Charles gently that "there has been some little misunderstanding" on the part of local interests, and that "without doubt Senator Cutting will take this matter up with the proper authorities." [5]

The Cutting-Charles correspondence signalled a wave of politically tinged negotiations between White Sands' boosters and the NPS. Job-seekers like C.C. Merchant of Alamogordo wrote to Senator Sam Bratton asking for information on applying for the position of "caretaker." Merchant knew Bratton only slightly, had never met Cutting and knew little of Congressman Dennis Chavez. More telling was the direct appeal of Emma Fall, wife of the former Interior secretary, to Horace Albright. Her family had come upon hard times during Albert Fall's lengthy legal proceedings and five-year prison term for the Teapot Dome scandal. The depression had wiped out the family investments in real estate, but Emma had opened in El Paso a "Spanish cafe," with a Mexican woman in charge. Local residents and tourists alike praised her cuisine and the cafe received good notices in travel literature. Mrs. Fall wanted the NPS to grant her a concession at White Sands for a branch of her "Amigo Cafe," with perhaps another license at Carlsbad Caverns. Horace Albright had to decline her offer, since plans had yet to be drafted for White Sands, and the caverns had a concessionaire that "up to the present time has not yet earned an adequate income." [6]

Once the new federal budget year began in July 1933, the park service decided upon a "temporary custodian" in charge of White Sands. Despite the appeals of Merchant and several other candidates, the NPS realized that Charles had the best credentials among local residents, to whom the service owed the creation of the monument. Unfortunately, the lack of funding for White Sands allowed Frank Pinkley to pay Charles only one dollar per month for his first year of service. Charles would also have to provide his own transportation over the fifteen miles of rutted dirt road to the dunes, and would have no office or supplies. Thus Charles' correspondence went out on stationery from his insurance company, or the Alamogordo chamber of commerce. [7]

Researchers working on the history of southwestern monuments have had the good fortune to read the "monthly reports" that Pinkley required of all his custodians. Hal Rothman and other students of the park service offer varying comments on the merits of these brief, sometimes colloquial statements that included visitation totals, lists of prominent visitors, commentary on the weather, and reports of construction. In Charles' case, his years as a journalist in Kansas, and later his free-lance articles promoting the Tularosa basin and the dunes, fitted him well to present his case to Pinkley for more staff and facilities. Visitation began with Charles' estimate of 16,540 for the month of August, a figure that stunned other SWNM custodians reading the monthly report. Charles could only count vehicles on Sundays (his day off from insurance work), and calculate the number of visitors daily by guesswork. He also spoke of the need for highway work, both in the monument and out from town, as he believed that his park service unit would host 500,000 people in its first twelve months. [8]

By Labor Day the SWNM superintendent had yet to arrive at White Sands, prompting Charles and his colleagues at the local chamber to plot their own strategy for construction work. The chamber had learned that Governor Arthur Seligman had appointed Jesse L. Nusbaum, former custodian at Mesa Verde National Park and by 1933 director of the Santa Fe-based Laboratory of Anthropology, to select twenty sites in New Mexico to receive work crews from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This was the most popular of FDR's work-relief programs, as it removed young single males from urban areas and placed them at work in the countryside. The CCC also required no state matching funds; a factor critical in New Mexico, where the entire state budget that year stood at only $8 million.

By September the Alamogordo chamber had asked Nusbaum for a 200-member CCC camp to begin road work at White Sands. Pinkley agreed, noting that the moderate winter climate could expedite construction. Nusbaum had to deny the request, however, as CCC regulations at that time prohibited work on federal lands. Alamogordo then immediately petitioned another relief agency, the Emergency Conservation Work program (ECW), for one of its winter crews. The NPS learned in November that the newly created Civil Works Administration (CWA) would take over ECW projects, and that a crew could begin soon on access roads, a parking area, boundary surveys, and restrooms built in a style that the NPS described as "Navajo hogan character." [9]

At the end of 1933, Tom Charles could reflect upon a satisfactory year at White Sands. He had shepherded the monument through the labrynth of state and regional politics, and had begun the arduous task of linking NPS strategies with local desires for usage. The state land commissioner had asked for revocation of President Hoover's withdrawal order of 1930, which had limited the state's ability to lease acreage surrounding the dunes, or to transfer school lands within the monument for acreage outside its boundaries. President Roosevelt lifted the withdrawal by executive order on December 6, 1933, allowing NPS officials to initiate correspondence with state and private landowners and claimants that would give the service unified control of the park unit.

Frank Pinkley finally managed to visit White Sands that October, praising the beauty of the dunes and promising help for road construction. Tom Charles' only regret was that Pinkley warned against excessive use of the dunes by local visitors, who drove over them, burned fire rings in the gypsum for their cook-outs, left trash middens behind, and carried away buckets of gypsum for personal use. Charles wrote in his October report to Pinkley that nature restored itself at the monument. "Tonight's mountain breeze will heal today's most tragic scar," he said, and described NPS rules as "the cold policy of 'undisturbed.'" [10]

For the remainder of the winter of 1933-1934, Tom Charles shared his monument with the work crew from the Civil Works Administration. No sooner had the laborers begun to cut an eight-mile clay-based road into the dunes than did Charles receive word from Santa Fe that all CWA projects would be halted. CWA chief Harry Hopkins disliked the national pattern of project directors exceeding his limits on the category of expenditures called "other than labor" costs (overhead). FDR's relief programs had been intended to place as many unemployed workers in jobs as quickly as possible, with a minimum of cost overruns or budget shortages; the easier to blunt intense conservative criticism that characterized the New Deal as "make-work" artificial solutions better left to the free market. [11]

The Hopkins edict would be the first of many such "stop" orders to plague New Deal work crews at White Sands and elsewhere. This echoed the experimental nature of the president's relief efforts, and contributed to the peripatetic nature of NPS policy planning. For Tom Charles, however, the solution was simple: contact political officials responsible and ask for guidance. Again he wired Senator Cuttting, who suggested that he correspond with Margaret Reeves, state director of the CWA. Charles told Reeves that his road project, then 25 percent complete, required heavy non-labor costs because crews had to be transported daily to and from the monument a distance of thirty-plus miles. In addition, the road crews utilized 24 horses drawing repair wagons, with resultant costs for feed, stables, and transportation for the animals. Margaret Reeves then told Charles to contact the congressional delegation for further advice on restoring supplies and materials to the 104-member CWA unit. [12]

Chaos within the national CWA office prompted custodian Charles to draft more letters to state officials. Hopkins' order that laborers be reduced to fifteen-hour work weeks led Charles to write to Senator Carl Hatch, who called the CWA to register a direct complaint. Then the CWA ordered all NPS custodians to terminate existing employees by April 26. This would allow a new set of CWA projects to begin elsewhere, and also fulfill "the President's intention of dispersing the C.W.A. forces into private jobs." Superintendent Pinkley could offer little hope to Charles or his CWA workers, who had no alternative sources of employment in the Tularosa basin. All he could advise was that Charles write a new proposal for road work, as "I have the feeling that about the time our forces are cut down to the point of inefficiency they [FDR's staff] are going to turn loose a bunch of money for us." [13]

Such promises neither built roads nor fed workers at White Sands. Tom Charles' February 1934 report noted that the CWA crew had to live in tents at the dunes, supplied with food and water until the resolution of the funding crisis. Senator Cutting then telegraphed Charles on March 7 with word that the CWA's Hopkins had released nearly $12,000 for White Sands work, primarily the overhead charges. Charles had solved his problem at the monument, but the directness of his appeals to Congress irritated NPS officials. A.E. Demaray, associate NPS director, wrote Pinkley that, while Charles had managed to gain the release of all statewide CWA monies for New Mexico ($200,000), "the correct procedure. . . would have been for you to take the matter up with [regional NPS authorities] and then report to this Office in case you were unable to secure action." Charles admitted "the mistake of wiring to Senator Cutting direct," saying "it was purely unintentional, of course." His only excuse was that "the local Chamber of Commerce was after me and threatened this and that." "I see now," he confessed, "that I should have let them handle the matter themselves." [14]

The strain of CWA funding took its toll on Charles and other NPS officials. The stipulation requiring 90 percent of workers to be unemployed limited the availability of skilled craftsmen. Then the CWA started shifting crews to other sites as warmer weather ensued. Crew members also had difficulty with the $6 per week wages, given the amount of time they spent away from their homes and families. Even the landscape architect employed at White Sands by the CWA, Laurence Cone, came in for criticism. He had devoted more time to discoveries of Indian artifacts and campsites than to advising the road crew on the proper route to cut through the dunes. Cone pleaded with Charles and Pinkley to spare his job, but the crew foreman, H.B. ("Hub") Chase, a son-in-law of Albert Fall, fired Cone on April 18, a week before completion of the project. Frank Kittredge, chief engineer for the NPS western office in San Francisco, visited the dunes in mid-April to examine the road situation. He attributed many of its problems to the haste with which it was planned. "It will be recalled that a special case was made of this project," said Kittredge, with "approval and authority to commence . . . granted . . ., based only upon a sketch map." The road was not in keeping with NPS standards of construction, through no fault of the CWA crew. Kittredge then learned of Charles' plans for a massive attendance on April 29 at the monument's dedication, and he urged the NPS to provide picnic shelters, restrooms, and parking facilities, and more staff (especially a full-time maintenance worker to clear the gypsum from the road). [15]

The CWA project ended just days prior to Tom Charles' planned gala dedication ceremonies. Several committees with prominent residents as members devised a host of welcoming activities. J.L. Lawson, a prominent lawyer and landowner who would later try to sell to the NPS his water rights to Dog Canyon ranch (the Oliver Lee property east of the dunes), served as chair of the "Old Settlers Day," where prizes would be awarded to the oldest and longest-resident Hispanic, Anglo, and Indian attendee. On the "reception" committee sat W.H. Mauldin, who had settled in 1882 in the nearby town of La Luz, and who was the father of the future Pulitzer prize-winning wartime cartoonist, Bill Mauldin. [16]

All who attended the day-long celebration realized the special nature of the event, and of the monument itself. Tom Charles estimated that 4,650 visitors arrived in 776 vehicles on the newly opened dunes road. During the afternoon the crowd cheered a baseball game played by two all-black teams, the Alamogordo Black Sox and the El Paso Monarchs. The Black Sox thrilled the "home-team" fans sitting on the dunes high above the playing field by winning 12-7, despite rumors that the Texas squad had utilized players from the Mesilla Valley. Then speakers addressed the throng on such topics as A.N. Blazer's "The Sands in the Seventies," George Coe's "Recollections of Billy the Kid," Harry L. Kent's "Origins of the White Sands," and Oliver Lee's "Early Days in New Mexico." [17]

The most touching moment at the opening ceremonies, all agreed, came when Albert Fall spoke on "Reminiscences of Early Days." Making his first public appearance since completion in 1932 of his five-year prison sentence, Fall brought tears to the eyes of his loyal partisans from west Texas and southern New Mexico. A reporter from the Alamogordo News noted Fall's infirmities (the reason for his early release from prison by President Hoover), and wrote that "it was indeed a pathetic sight to see that he had to be assisted from his car and supported during his talk." After a few remarks, Fall had to be seated, and the crowd strained to hear his voice. He thanked all who had come to hear him, and prophesied: "I suppose this is the last time I will meet the old-timers." Then, in a stunning reversal of form that few listeners could detect, Fall closed by praising the park service and local interests who had fought for White Sands. Said the reporter for the Alamogordo Advertiser: "He [Fail] told of various attempts to exploit the Sands commercially, all ending in futility, and stated his opinion that very appropriately they are now put to the best use possible, reserved for their scenic beauty and attractiveness." [18]

Although NPS records do not show it, attendance at White Sands' opening-day festivities had to catch the eye of public and private officials alike. Most units in the Southwest did not record 4,650 visitors in a whole year, and White Sands' distance from major population centers made the day all the more remarkable. In 1934 El Paso, one hundred thirty miles away by dirt roads, had 105,000 residents, and provided the bulk of out-of-town visitation. No other community within 200 miles had more than Albuquerque's 27,200, and Alamogordo's 3,100 people came often that summer. Indicative of the variety of visitors was the party from the New Mexico School for the Blind. Some 100 youths and staff members, including school board member Bula Charles, spent June 1 cavorting in the dunes. The school superintendent told Tom Charles that "no place else can the blind children turn themselves loose with such freedom." [19]

Both the park service and local boosters agreed that White Sands should be promoted advantageously, so that attendance would generate financial support from the FDR administration. The New York Times on May 15 carried an NPS press release on the dunes that caught the attention of Frederick A. Blossom, librarian at the Huntington Free Library in New York City. The park service's own film maker, Paul Wilkerson, came to White Sands in October to prepare a newsreel for distribution in the nation's movie houses. Then in November the National Geographic Magazine accepted Tom Charles' invitation to visit the dunes and craft a photographic essay. The chief NPS photographer, George Grant, spent several days in the Tularosa basin and surrounding mountains seeking unusual stories. He found most appealing the proximity of the dunes to the Lincoln County War. "Every school boy wishes to know about Billy the Kid," said Grant. As there was "no place where this information is available, all in one spot," and that this was "the first time perhaps that the Billy the Kid story has entered the National Park Service picture," Grant urged Charles to develop such a connection for the "transcontinental travel" about to come to the monument. [20]

Increased visitation and publicity for White Sands also attracted Governor Andrew Hockenhull, who had been approached by organizers of the 1934 Chicago "Century of Progress" exposition. Hockenhull wanted New Mexico to fill its building at this "world's fair" with outstanding examples of the state's charm and exotica. He asked Tom Charles in May to chair the Otero County fund-raising campaign, seeking $300 for the building. Charles energized his diverse community by planning a series of dinners and dances for the Anglo, Hispanic, and "colored" population of Alamogordo. The black "colony" in town had never been asked to join in a community-wide program, and thus could not accommodate Charles' request on such short notice. The Anglo and Hispanic venues, however, raised $324, allowing Charles to make White Sands the centerpiece of the New Mexico building. The floor of the building was covered with gypsum, and NPS officials received many compliments from the thousands who visited the Chicago exhibit. [21]

All this notoriety would be in vain, however, if Tom Charles could not improve transportation to the dunes. In March word filtered out of Washington that New Mexico would receive $6 million in new federal highway construction funds. State engineer G. D. "Buck" Macy informed Charles that he would authorize grading and oiling of the fifteen miles of State Highway 3 to the dunes, at a cost of $300,000-400,000. "Boy, how the crowds will pour in," said Charles, as the Tularosa basin would now be linked to the national highway network from North Carolina to Los Angeles, which Charles described as "over 90% completed." [22]

Unfortunately for White Sands, plans for the road had also interested others, including Mr. and Mrs. Frank Ridinger, who built a gasoline station and small motel at the "Point of Sands," one mile southwest of the White Sands turnoff, and also the "Southern Dusting Company" of Tallulah, Louisiana. The latter was merely the latest in a series of speculative mining ventures in the dunes. The company had leases around Lake Lucero, and wanted to drill for sodium compounds. They also wished to cut a road to the lake bed along the western boundary of the monument. Tom Charles feared that he could not police the area, especially if auto racing took place on the long stretches of alkali east of Lake Lucero (later to be known as the "Alkali Flats"). [23]

Less easy to dismiss was the presence of the Ridinger family. Frank Ridinger, a veteran of World War I, his wife Hazel, and their three daughters had obtained a lease from the state land office prior to 1930 to build their small way station on the Alamogordo-Las Cruces highway. In the spring of 1934 they became irritated at the presence of Tom Charles in the monument area, whom they believed sought the termination of their lease. Then in April the Ridingers asked the park service for permission to manage a concession at the opening ceremonies, only to be rebuffed. Hazel Ridinger wrote a strong letter of protest to Frank Pinkley, accusing Charles of distorting the truth. "We have ignored his [Charles"] petty prissy tooting" that he was a "government man," said Ridinger, and claimed that "T[.] Charles['] one interest in the Sand is and has been personal publicity." She claimed that her family had "ten local friends to [Charles'] one," and asked the SWNM superintendent to visit the dunes to verify their claims. [24]

For the rest of the summer, Tom Charles and the park service pressed for closure of the Ridinger affair. The custodian denied infringing upon the Ridingers' business, nor that he wanted them removed before completion of the U.S. Highway 70 project. Pinkley did not see this incident at first as serious, in that he had several similar "young feuds on our hands at other points in the [SWNM] system." He informed Mrs. Ridinger that she had "ascribed to personal animosity on Mr. Charles' part what was in fact only enthusiasm for the monument." But the Ridingers remained unmollified, and in September Pinkley asked his assistant superintendent, Robert H. Rose, to contact the New Mexico state land office to terminate the Ridinger lease when it became eligible for renewal in October. Rose volunteered to spend a night at the motel to verify charges that the Ridingers were rude to monument visitors, and also because Tom Charles had learned that Frank Vesely, state land commissioner, would accede to the NPS's wishes if they wanted the Ridingers gone. Vesely made good on his promise, and the Ridingers turned to the politically connected Judge J.L. Lawson for help. Lawson, most recently a participant in the White Sands opening ceremonies, asked Vesely to let the Ridingers at least sell the lease to earn some income for their troubles. [25]

The Ridinger case remained a disappointment for Charles, but the NPS had to address other land-use issues generated in the Tularosa basin. The Alamogordo chamber of commerce had asked Senator Hatch to petition the park service to purchase timber lands near Cloudcroft for inclusion in a national park. The impetus came from passage in Congress that year of legislation that permitted purchase of "submarginal lands" to remove them from cultivation or harvest. Conrad Wirth, assistant NPS director, informed Hatch that the service "could not consider this area . . . unless it was an outstanding example of a major type of American scenery." The park service did, however, advise President Roosevelt to release on November 28 Proclamation No. 2108, expanding White Sands by 158.91 acres. The New Mexico state highway department had redesigned U.S. 70, and the NPS needed this acreage just south of the monument boundary to guard against future commercial development. Tom Charles had learned that "one of the leading boot-leggers [vendors of illegal liquor] of the community has an idea of homesteading it for business purposes." Then late in 1934, local civic officials mounted a campaign to have the NPS purchase as a "wildlife refuge" the lake and well of L.L. Garton. Frank Pinkley doubted whether the "lake" could be of significant value to White Sands, but promised to explore these petitions in the near future. [26]

|

|

Figure 7. Frank and Hazel Ridinger's White Sands Motel (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

The Garton well issue would mature the following year (1935), as would plans drafted in November 1934 by Robert Rose for a museum at White Sands. For the next six years the park service would design, construct, and outfit a museum and visitors center at the dunes that park officials would consider one of the best in the system. Pinkley's assistant superintendent predicted that the facility, which Rose wanted built in the shape of a cross (with a lobby in the center and exhibit space on the wings), would address three themes: high visitation; the need to explain simply the dunes' complex ecosystem; and the real probability of expansion in the future. "Here in the White Sands," said Rose, "we have one of the finest places in the National Park Service system to teach that principle of 'Adaptation to Environment."' Just one year earlier, the NPS had released a study by George M. Wright, et al., Fauna of the National Parks of the United States (1933). The authors called upon the park service and Congress, in the words of Alfred Runte, to "round out the parks as effective biological units." The monument may have been reduced in size because of commercial and political pressures, but Rose believed that enough remained of the dunes "to satisfy that intellectual curiosity by bringing people in contact with the natural wonder or scientific feature itself." [27]

Rose's recommendations became the baseline data for the next six years of museum planning and construction. The facility itself would not open to the public until 1938. Yet his idea to emphasize natural history over that of humans was in keeping with NPS logic to present the story that the park itself revealed. Rose did, however, cite the need to embrace more fully the life of the nearby Mescalero Apaches. A young anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Moms Opler, had researched the Mescaleros and other bands of Apaches in the 1930s Southwest, and spoke in September 1933 at the dunes to a group of Alamogordo Rotarians about "the habits of the Mescalero." Rose knew of local interest in these native people, and reported to the NPS: "Unless some archeological national monument reasonably close to the Mescalero Reservation can lay stronger claim to a full and complete treatment of the Mescalero Apache, these modern Indians should be made the subject of exhibits" at White Sands. [28]

The theories of Robert Rose had a basis in fact, as White Sands would count 34,000 visitors in both 1934 and 1935. Tom Charles constructed a registration box at the park entrance, asking patrons to indicate their hometowns and size of party. He did so only after Superintendent Pinkley requested "a detailed report of the contact which I [Charles] make about the White Sands;" a condition he considered "too big an order at the present salary [$1 per month]." Charles would make an average of three trips per week to the dunes, stopping cars of picnickers to inquire about their well-being. Charles also met a steady stream of visitors in his Alamogordo insurance office, and handled all correspondence, publicity, and report-writing there. Among the less pleasant aspects of Charles' custodial work were the appeals of the unemployed for work. One such individual was W.A. Warford, a 48-year old San Franciscan who had not worked for four years. Needing to support his wife and five young children, Warford wrote to Charles seeking a position as a foreman in a White Sands CCC camp (which unfortunately did not exist). [29]

For every W.A. Warford, however, there were other information-seekers more interested in the growing publicity around the dunes. The newly elected governor of New Mexico, Clyde A. Tingley, would make tourism promotion a critical feature of his economic program. The first liberal Democrat to sit in the governor's office in the 1930s, Tingley assiduously cultivated President Roosevelt and his New Deal officers, often joining FDR when the polio-stricken president spent time in the nearby Hot Springs/Elephant Butte area. Tingley would also apply for every conceivable federal grant, and work with the state's congressional delegation to receive dispensations from matching-funds regulations (by 1938 New Mexico ranked last nationally in its share of state matching funds; three-quarters of one percent). This would benefit the Tularosa basin and White Sands financially, but would also intensify the political influence of the Democratic party, which had not been able to overcome the power of the Republican/Bronson Cutting network (to which Tom Charles belonged). [30]

The state's initiative in tourism promotion found an eager participant in Charles. As the "temporary" custodian learned more about the growing national fascination with the dunes, he developed new plans for maximizing publicity. The photographs and text of the July 1935 National Geographic Magazine story pleased Charles when he saw an advance copy. "We will make any sacrifice to get a good spread in the National Geographic," Charles told NPS photographer George Grant. Friends wrote Charles when they read the story, such as W.D. Bryars, one of the early promoters of the monument. "It is a master stroke and means a very great deal," said the Santa Fe judge, who concluded: "The people of [southern New Mexico] and of the entire state are eternally in your debt." [31]

The National Geographic article triggered a substantial increase in visitation and out-of-state inquiries to the New Mexico state tourism office. Charles furthered this effort with inauguration in early May of "Play Day," a gathering of Otero County school children, their teachers and parents. Building upon the success the previous year with the dedication ceremonies, Charles saw Play Day as an excellent opportunity to reward the citizens of the Tularosa basin for their support. More than 3,500 people gathered for a picnic, concert, and games at the dunes. Among the attendees were 35 children from the Mescalero Apache reservation school; a sign of Tom Charles' continuing commitment to incorporate them into the monument. Play Day thus became the centerpiece of White Sands' activities, expanding within a few years to include schoolchildren and college students from west Texas and southern New Mexico. [32]

Its success, and that of the park service at the dunes, also impressed Thomas Boles, superintendent at the nearby Carlsbad Caverns. Boles, whose lukewarm endorsement of the creation of White Sands had required the second opinion of Roger Toll, had reason within four years to change his mind. "I have always felt," said Boles, "that the Caverns' biggest competitor in the Southwest was the Grand Canyon." After the summer travel season of 1935, however, "the showing made by the White Sands" led Boles to realize that "perhaps my real competitor is much closer," a situation that would become even more apparent when "you [Charles] get a paved highway between Alamogordo and Las Cruces." [33]

|

|

Figure 8. Roadside Sign for White Sands West of Alamogordo (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

White Sands could not bask in the glow of such compliments as those paid by visitors or park service superintendents. The heavy volume of traffic, small staff, and modest budget strained not only the landscape but relations between Tom Charles and his superiors. The custodian worried in February 1935 at the slow pace of construction at the monument. Charles would entertain dignitaries like Governor Tingley at Play Day, with no shade, fireplaces, running water, or lavatory facilities for visitors. Then at Play Day disaster struck as "there was a constant waiting line of from five to twenty women" to use the crudely built, temporary toilets in the dunes. The expensive ($500 each) lavatories built in the "Navajo hogan" style at the park entrance, five-and-one-half miles away, went unused, and Charles questioned the logic of NPS designers and consultants who never attended his ceremonies nor asked local residents their opinion of the monument. "I have had severe criticism on this subject" from civic leaders in town, said Charles, and the custodian told Pinkley that he could no longer "hold my tongue." [34]

Charles' dialogue with his superiors developed simultaneously with the grandiose plans of local and regional interests for White Sands. As Charles requested better picnic facilities, J.B. Willis of El Paso asked the NPS for a lease to construct "a large bathing beach, dance pavilion, and other accommodations for the visiting public." Then Pinkley learned that Alamogordo officials envisioned a permanent baseball field, swimming pool, horse track and fairgrounds for the dunes. What ensued was a flurry of memoranda that revealed not only the difference between NPS policy and local ambition, but the distinctiveness of White Sands within SWNM. [35]

The essential problem of White Sands for NPS personnel was the intensely local character of visitation and promotion. Tom Charles' superiors sat in offices in Washington, San Francisco, Casa Grande, and Oklahoma City, and traveled constantly to dozens of park units. From this came a decidedly national perspective on park management, linked to classic Progressive concepts of aesthetics and preservation. To Charles and his peers, the dunes remained what they had always been: a place for recreation. "As I see this," said Charles, "it is not a matter of what the Monument was created for." The park service needed to remember that "we have . . . to take care of the actual needs of the people who visit here." Pinkley became quite sarcastic at Charles' reading of public service, charging: "Where is your authority there for making a Southern New Mexico playground?" The local chamber then decided to approach Governor Tingley and the state's U.S. senators to bring pressure on the NPS, leading Pinkley to demand rhetorically: "How are you going to make sure the local Chambers of Commerce won't try to make a young Coney Island out of the White Sands at the expense of the United States Government?" [36]

As long as the debate over facilities remained within park service channels, the issue of competing philosophies rarely surfaced. It was when civic leaders protested directly to Washington that the larger implications of the Charles-Pinkley correspondence became clear. A.E. Demaray wrote to E.H. Simons of the El Paso chamber of commerce to explain the controversy raging within the park service. San Francisco and Washington staff wanted all development clustered at the park entrance, "so [that] the visitor may get the unique experience of seeing a world without vegetation." The staff wanted "man-made intrusions" left out of the heart of the dunes, allowing the visitor, in Pinkley's words, to engage "the vast silence and weird beauty" of this "sacred area." Such patrons, whom Pinkley called "national" visitors, came "from far distant states . . . to get the full thrill of the White Sands." Pinkley offered no statistics on the volume of national visitation, and by the end of 1935 no clear resolution seemed at hand. [37]

The conflicting pattern of booming attendance and NPS reluctance to accommodate local demands led civic officials to explore alternatives in the vicinity of the monument. Fortunately, a rancher named L.L. Garton owned property immediately south of U.S. 70 within one-half mile of the park entrance. Garton and previous owners had tried to develop the acreage, which included the only easily accessible potable water between Alamogordo and White Sands. Garton had purchased 1,240 acres around the well in 1916, after a group of Otero County businessmen had failed to discover oil on the property. They did find "mineralized" water at 94 degrees Fahrenheit; too alkaline to grow crops like cotton, but warm enough to provide area residents with the equivalent of a "hot-springs resort." In 1930 Mr. Garton stocked his "lake" with muskrats, black bass, sunfish, bullfrogs, and oysters to create an "aquatic farm" for the enjoyment of his guests. Four years later this experiment had also failed, and Garton entertained inquiries from Dr. F.B. Evans, president of the Alamogordo chamber, and NM A&M president Dr. Harry L. Kent to sell the land to the park service. [38]

In order to ascertain the merits of the Garton property, the NPS in March 1935 sent Ardey Borell, SWNM naturalist technician, to White Sands. His six-day visit impressed Borell with the abundance of waterfowl in the high desert (53 species of birds). "At present very few Western Parks or Monuments provide sanctuary for waterfowl," Borell informed his superiors, a circumstance that Garton's sale to private owners would jeopardize. Borell's conclusions about the lake's ecological value meshed with the report of Tom Charles' son, Ralph Charles, who served in Las Cruces as a "land planning consultant" for the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB). Ralph Charles had written in December 1934 that Garton, then aged 75, would sell the entire property at low cost. From this "recreational possibilities could be developed," as well as the bird refuge, an opinion echoed in January 1935 by Elliott Barker, New Mexico state game warden. [39]

What convinced park service personnel to pursue the Garton property was the potential to develop the lake's water resources for visitor use at the adjacent monument, and the applicability of construction funds from the Resettlement Administration's "submarginal lands" program. This agency was part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's efforts to restore lands no longer of value to farmers and ranchers. Tom Charles had tapped the water supply at the dunes, providing visitors with a highly alkaline but drinkable source of water. Yet he and his superiors knew that a better supply, with much greater volume, had to be identified soon. Garton's well needed to be tested for its feasibility, and NPS officials in the regional office in Oklahoma City began the paperwork for purchase that summer. [40]

The Garton case then entered the complicated network of New Deal/park service collaboration, setting a pattern that persisted for the remainder of the decade. In early August a sixty-year-old man from Marshall, Texas, came to Tom Charles' office, identifying himself as John Happer, "manager" for the Garton project. Charles had no advance notice of Happer's work, and hastily wrote Pinkley that "this is all Greek to me. The SWNM superintendent concurred, asking western NPS staff for an explanation. Frank Kittredge of San Francisco complained: "There appears to be quite a duplication and lack of information on the part of the Park Service in this matter." Then John H. Diehl, SWNM engineer, went to White Sands to investigate. He learned that Happer had been sent by L. Vernon Randau, the NPS official in Oklahoma City in charge of "Recreational Demonstration Projects [RDP]." Happer was not needed for at least thirty days, said Diehl, as no surveys had yet been conducted nor leases signed. [41]

The Happer incident was not the first instance of New Deal problems at White Sands, but it did echo the ambiguities of the monument's early years. Without the large amounts of non-NPS funds for land acquisition and facilities construction, White Sands may have remained as Tom Charles found it in 1933. Yet the lack of park service control led to strained relations with nascent agencies like the Resettlement Administration, and its successor the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Such bodies had no permanence like the NPS, no clear mission beyond relief employment, and no stable chain of command. For these reasons the RDP and the WPA work at White Sands could be vulnerable to political intervention at all levels (local, state, and federal), further irritating career park service employees who had their doubts about the proper path for White Sands to take.

To make himself useful, John Happer traveled around the Tularosa basin inquiring about the need for his services. Charles and Pinkley exchanged bemused letters about Happer's frenetic pace, with Pinkley sarcastically noting that "Happer is sort of out on a limb. . . and is afraid some one will come along and catch him doing nothing and fire him." In September Pinkley received unofficial notice that the Garton project would have $50,000, which he wanted to apply to the monument as well. He found it ironic that the park service could not finance "a custodian's residence, public comfort station [restroom], water and sewer systems, equipment shed and administration building." More revealing was the fact that "the Government has not called on Mr. Garton. . . for abstracts." Happer had no "specific information concerning the amount of money to be spent or the nature of the project to be undertaken." Pinkley wanted Garton Lake to have only "fencing and the construction of a few relatively inexpensive dykes" for the wildlife refuge, and he regretted supporting the purchase in December without knowledge of the lavish funding provided by the Resettlement Administration. [42]

The pace of New Deal spending, countered by NPS desires to approve projects through channels, propelled Garton Lake into turmoil. Evidently other federal agencies had similar complaints against the RDP. In early November 1935, Ralph Charles sent a quick note to his father with rumors of suspension of all resettlement work. Yet Ralph Charles also learned that federal officials wanted White Sands ready to restart Garton Lake at a moment's notice. John Happer proceeded to acquire Mr. Garton's abstract of his deeds and patents. Happer saw mention of several oil leases on the Garton property held by out-of-state residents, but believed that these had been proven worthless, and that quit-claim deeds could be secured rather easily. [43]

Once the funding for Garton Lake had been restored, Tom Charles discovered the full magnitude of political involvement in the project. Several WPA contracts in the Alamogordo area had started that fall, depleting the source of competent labor. This affected Garton Lake when Happer informed NPS that his assistant would be Frank Cunningham, an elderly man whom Tom Charles had known for nearly thirty years. Cunningham would be responsible for all survey work on the White Sands RDP, even though Charles reported: "He may be the best surveyor in the state, but if he is I do not know it." When confronted by NPS officials about Cunningham's qualifications, Happer said, in the words of Jack Diehl: "It was not any concern of ours . . . and . . . that he was the boss on that job." Tom Charles then clarified the issue for the NPS: "[Cunningham] is rather diplomatic in handling men, gets along well with the Bronson Cutting faction politically, and I do not take it as a life and death matter whether he is the engineer out there or not." Pinkley then concurred, telling Diehl: "We will just have to make the best of it, recognizing that we have to adjust ourselves to the Works Progress Board." [44]

|

|

Figure 9. Early Registration Booth (Restroom in Background) (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

With the Garton project set for construction in 1936, Tom Charles could plan that winter for maximizing visitation. His efforts would result in a forty percent increase (to 48,000), and NPS would in turn change Charles' status (to permanent custodian), and increase his salary, from $384 per year to $540. White Sands was the theme of a float in the Sun Bowl carnival parade in El Paso on New Year's Day, winning first prize in its category. The Rock Island railroad wanted to include the dunes in its promotional literature for a circle tour through the Mescalero reservation, Cloudcroft, and Alamogordo. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) wanted to reprint Charles' July 1932 article in New Mexico Magazine in the July 1936 issue of their own national publication, which had New Mexico as its theme. Always eager for wider coverage of the dunes, Charles rewrote the piece to reflect changes since the NPS took over White Sands. Elsie Aspinwall, DAR officer for the state, marvelled at Charles' helpfulness, and promised to send house guests to the monument as part of their tour of the Grand Canyon and Carlsbad Caverns. [45]

Charles' notoriety as a publicist for his monument also attracted the attention of the WPA, which in 1936 inaugurated the Federal Writers' Project (FWP). As part of the larger goal of WPA artistic and cultural programs, the FWP had two major emphases in New Mexico: preparation of the state travel guide (published in 1940), and organization of the "Historical Records Survey." Ina Sizer Cassidy, director of the state FWP, asked Charles for his advice on developing a data base of public and private materials for research on New Mexico's past. She also acknowledged Charles' role as a promoter of history in southern New Mexico by asking him to serve on the survey's advisory board; an honor which Charles had to decline, citing his growing work load at White Sands. [46]

The tradition of special visitation at White Sands added Easter services in March, when some 300 residents of Otero County came to the dunes to pray at sunrise. By day's end an additional 1,200 visitors had converged upon the monument. This built momentum for Play Day, with attendance at 3,500. Among the activities appealing to the crowds were "Camp Fire Dances" by the "Mescalero Boy Scouts." Charles Lindbergh Shanta Boy, aged seven, drew much applause for his efforts. Other dancers included Wendell Chino, who twenty years later would commence his long tenure as the Mescalero tribal president. Then on July 4th, White Sands hosted an Independence Day picnic that lured all the state's major political leaders (Governor Tingley, Senators Chavez and Hatch, etc.), each eager for voter recognition in the campaigns that year. Senator Chavez then returned with Hatch and Tingley in early August to speak at the dedication ceremonies for completion of the U. S. Highway 54 project (from El Paso to Alamogordo). Among his remarks at the dunes, Chavez called the park service "one of the finest groups in the employ of the Government." [47]

Praise for NPS work came in conjunction with planning for the permanent facilities that would enhance visitors' experiences. The NPS branch of plans and designs had difficulty agreeing upon the location of the visitors center, museum, and headquarters complex. Frank Kittredge rejected the White Sands master plan in 1935 and 1936 because of these differences of opinion. Kittredge wanted the entire compound back in the dunes, so that visitors had to venture into the monument and thus engage its distinctive ecology. The presence of WPA workers made it imperative for NPS staff to draft their final plans. John Happer also took charge of the headquarters work, but could not use his full allotment of WPA funds until design figures were in place. Tom Charles wrote to Pinkley warning of the loss of "50 to 60 percent of the money set up for that project." Then Happer learned that he would use all his funding before July 1, and had to negotiate with the NPS and WPA for access to other revenues. The U.S. Department of Labor then set wage rates from 20 to 25 percent higher at White Sands, based upon application of the Davis-Bacon Act rules to the Alamogordo area (Davis-Bacon adjusted wages on federal projects to align local rates to national standards). NPS auditors took note of the excessive costs at White Sands, but believed that it could not interfere at present. Said George Collins of the regional NPS office: "[The] history of RDP work at White Sands and general relationship down there would, we think, bring out a good deal of local controversy not unmixed with politics." [48]

Contributing to Happer's woes at White Sands were the unexpected legal delays caused by the mineral-rights leaseholders at Garton Lake. Happer solicited testimonials from NPS and state officials to the scarcity of oil on the property, hoping that this would suffice to release federal funds. Tom Charles also asked for monies for road construction in the monument, as three accidents at the park entrance in February and March caused two fatalities and serious injury to nine other passengers. The failure of the well casing also harmed plans for the bird sanctuary, as muddy water and botulism (alkali poisoning) killed fish and fowl alike. Then the leaseholders either refused to deed their claims to the NPS, or tried to get more money from the government than the appraised mineral value. [49]

|

|

Figure 10. Grinding stone unearthed at Blazer's

Mill on Mescalero Apache Reservation (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

The year 1937 marked a turning point for White Sands and its benefactor, the Roosevelt administration. Because 1936 had been an election year, FDR's staff had released large sums of money for public works projects to attract voters' attention. This strategy thus increased White Sands' emergency relief monies by a factor of 39, from $2,400 in fiscal year 1936 to $78,161 in the following year. For the next three years White Sands received smaller, though still substantial grants for construction work, so that by 1940 the federal government's relief investment topped $256,000. Completion of highway paving and the visitors center-headquarters complex owed much to this generosity. In addition, the NPS could mount a serious campaign to identify a stable source of water for the expanding visitation base (108,000 in 1937, a figure not to be matched until after World War II). [50]

The infusion of such federal capital made Tom Charles' role at the monument less critical than when he served as the only park service representative at the dunes. WPA construction of employee residences brought more staff, which in turn changed the strategy for counting visitors. Early in 1937 Frank Pinkley asked Charles to adjust his numbers for variations in weekday and weekend usage. To do so, Charles and a " Barry Mohun (the son of a wealthy eastern family who paid his salary at White Sands for six months), counted cars for 59 days, compared these to the written registrations, and calculated that 14 percent of all visitors signed the log book at the dunes entrance. Then in November, Pinkley sent Jim Felton to White Sands for the express purpose of greeting all patrons at the newly opened visitors center. A discrepancy occurred immediately in December, as Felton's daily eight-hour count of 1,830 visitors clashed with Charles' formulaic estimate of 4,742. [51]

By whatever numbers one cited, White Sands' popularity grew dramatically as facilities and transportation access increased. In July the SWNM reported visitation at the dunes had exceeded 12,400. More intriguing were comparisons of attendance for all SWNM units since 1935. That year White Sands contributed one-sixth of all visits to the region's monuments; in 1936 this grew to forty percent, and 35 percent in 1937. To make the point more clear, SWNM contrasted White Sands with Capulin Mountain National Monument, a dormant volcano crater along U.S. Highway 87 in far northeastern New Mexico. In July 1935, Capulin had outdrawn White Sands (5,000 visitors to 4,755); yet within two years the dunes had doubled the visitation of the New Mexican volcano (12,421-6,000). One reason for this surge was the inclusion of Independence Day as a major feature of the White Sands' calendar. Charles counted an astonishing 1,877 vehicles in the dunes that day. Then Isabelle Story of the NPS public affairs office wrote a piece for the New York Times entitled, "Oases for Tourists." Featuring Death Valley, Bryce Canyon, and White Sands, the October 17 feature coincided with dedication ceremonies for the headquarters' parking lot, where 1,200 guests listened to the 100-member Alamogordo High School band. [52]

The pride of the monument was the ambitious design for its museum. First attempted three years earlier by Robert Rose, planning for the White Sands story devolved upon Charlie R. Steen, the young archeologist who operated out of Santa Fe. Steen believed that the sequence of museum cases at White Sands should tell three stories. The first would be the origins of the dunes in the gypsum deposits of the San Andres mountains. Following this should be the ecology of the White Sands. Finally, the museum cases needed to tell the ethnology of the Mescaleros and the early Spanish exploration of the Tularosa basin. All of the design, felt Steen, should be tasteful and simple, as the museum occupied a structure built in the highly popular regional style of "Spanish colonial," or "adobe" architecture. This distinctive form, made prominent in Santa Fe in the 1920s and 1930s by architect John Gaw Meem, would be more renowned in northern New Mexico, where descendants of the seventeenth-century Spanish colonists resided. Thus the White Sands compound reflected the broader view of the park service, whose regional headquarters in Santa Fe (also done in adobe style) was under construction that same year. [53]

Structural work at White Sands took a precarious turn in the summer of 1937, as the now-familiar "change orders" coming from New Deal officials jeopardized production schedules and funding. The debate over location and extent of the picnic area persisted throughout the year, as Thomas C. Vint, chief NPS architect, argued for its placement on the edge of the dunes. Charles Richey claimed that Vint's idea had been scuttled (despite its inclusion in the master plan) because "Custodian Charles will arouse much local opposition to a permanent picnic site out of the better sands area." C.H. Gerner of the Washington NPS office had to remind his colleagues that disagreements over the picnic area endangered the substantial sums of New Deal money authorized for White Sands. [54]

Further complicating construction at the dunes in 1937 were charges that political appointee John Happer had mismanaged contracts for the RDP facilities. In Happer's defense, NPS officials realized in March that pressure to liquidate all WPA accounts by June 30 (the close of the fiscal year) meant acceleration of work, while new regulations demanded that 95 percent of all labor be from the unemployment rolls. The NPS regional office offered Happer the logic that haunted all New Deal programs: "If there is such balance of funds [on June 30] it will be a definite reflection upon the sincerity of our request for funds and on our ability to administer the project." Happer responded by asking permission to hire 100-110 workers to make adobe bricks for the pueblo-style architecture, and to send "a crew to the [Sacramento] mountains to cut vigos [sic], savinos [sic] and canales" for the roofing. Then in June, Happer received word that relief projects would be reduced 35 percent nationally, with White Sands to have only 70 workers for fiscal year 1938. [55]

For reasons of fiscal and managerial reform, the NPS moved in July to replace Happer temporarily with John H. Veale of the western office in San Francisco. Happer had not been a park service hire, and replacing him fit the NPS strategy to assume control of all work within its units. "I find that conditions are rather more serious than we anticipated," Veale wrote to the regional office in Oklahoma City. He blamed Happer not for his "carelessness" but for his "lack of appreciation of accurate and proper job records, and insufficient administrative inspection." Happer would spend payroll sums for labor in the wrong categories, causing both shortfalls and excess balances. Worse was the failure to maintain proper inventories of materials, with no balances whatsoever. Given the increased volume of construction work on site, the NPS could no longer afford such employees as the politically connected Happer, replacing him permanently with the well-respected John Stephens. [56]

|

|

Figure 11. Nineteenth-Century Spanish carreta and replica

in Visitors Center Courtyard (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

|

|

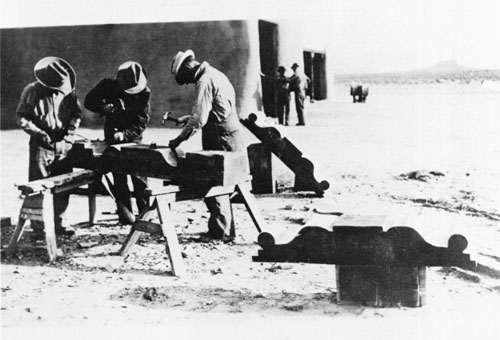

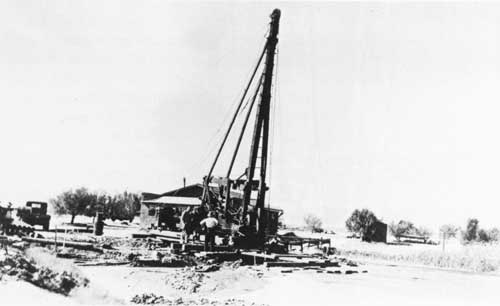

Figure 12. Pouring gypsum for road shoulder construction (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

|

|

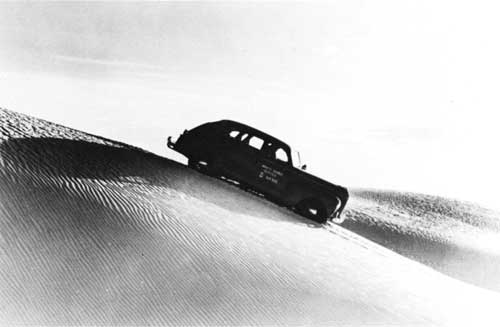

Figure 13. Blading gypsum road into the heart of the sands (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

|

|

Figure 14. Hazards of road grading (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

Beyond the monument's boundaries, the state of New Mexico added to the pressure for quick completion of the visitors center and headquarters compound. More claimants like Eugene Stevens, of Batesville, Arkansas, surfaced to petition the state land office for mineral leases at White Sands, while Jack Guion of Los Angeles declared that his grandfather's and uncle's graves (which lay on monument property) entitled him to claim acreage around their plots. Then the state wanted to trade gypsum lands within the park for acreage outside; a situation that puzzled Tom Charles, who believed this issue had been resolved in 1932 when "Mr. Hinkle [then-state land commissioner] definitely committed the State to the policy of an immediate exchange." [57]

While the state land office sought closure on mineral and other lease claims, the New Mexico highway department threatened facility planning at White Sands by shifting the path of U. S. Highway 70. The old gravel road had run along the southeast face of the dunes, then turned eastward to Alamogordo. Because of fears of drifting, the state wanted to retain control of the roadway. Unfortunately, the new route would cross monument lands, and federal law prohibited expenditure of U. S. highway funds on such property. Either the NPS would have to pay for this section of road work, or the impoverished state of New Mexico would be liable. Given that scenario, the state preferred to reroute U.S. 70 altogether, designing the road due east from Las Cruces to the intersection with U.S. Highway 54 at Valmont, some ten miles south of the monument entrance. Hurried correspondence between NPS officials and the state revealed that federal money could indeed be expended. Governor Tingley, with an eye on the upcoming 1938 campaign, promised not only to get funding for the White Sands section of U.S. 70, but to have the entire route blacktopped; a situation that the politically astute Tom Charles called "'just before election' news." [58]

With vastly increased visitation, new transportation links, and completion in sight of the headquarters complex, White Sands then faced its most critical test of 1937: securing a more stable water supply than that available from shallow wells in the dunes, from the city of Alamogordo, or from Garton Lake. In the case of the dunes proper, Tom Charles had learned from a group of Hispanic laborers at the monument that "there used to be a spring of sweet water within two or three miles of headquarters." Since they could not establish its location, Carton Lake received NPS attention. Then in November 1936, the drilling rig operated by Kersey and Company fell into the Carton well, with retrieval and re-drilling costs set at prohibitive levels. As for the municipal supply at Alamogordo, the NPS brought water from town and stored it in a pressure tank for staff use only; visitors still had to carry their own. When asked if the town could sell a larger volume, which would be sent via pipeline to the dunes, the mayor replied: "At times our water is scarce." Frank Pinkley thus advised the Santa Fe regional office: "On an approximately equal basis, this office would much prefer to own its own water system." [59]

That source of water, the NPS hoped, would come from the mountain spring 12 miles east of the dunes owned by J.L. Lawson. First discovered by ranchers in 1850, the spring was diverted for extensive use in the 1880s by Oliver Lee. In 1907 the territorial legislature of New Mexico, as part of its efforts to achieve statehood, created the office of territorial engineer, among whose duties was identification of all water rights claims. Because the 1907 law did not extend to "domestic" use (including stock raising), the Lee claim in Dog Canyon transferred in 1910 to Judge Lawson, who also received 440 acres for the hefty sum of $10,000. Lawson, whom NPS attorney Albert Johnson described as "a lawyer of Alamogordo who was inimical to the Government," supposedly in a fit of pique offered to sell Dog Canyon and its water for $2,500; a deal that federal officials pursued secretly so as not to alarm other landowners or boost the sales price. The NPS sent Charles and attorney Johnson to negotiate the sale, paying Lawson $3,000 for an option on his land and water. Then a park service contract examiner, Prentice Lackey, discovered that Lawson had paid the state land office only $66 of a total of $1,320 for title to public acreage in Dog Canyon. Until the remainder was paid to the state, the park service could not begin construction of an estimated $63,000 pipeline project to carry Dog Canyon water to the monument. [60]

|

|

Figure 15. Adobe style of construction of New Deal Agency work crews (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

The travel year 1938 (October 1937-September 1938) marked the first time since its inception that White Sands could boast of "full-service" status. Completion of the visitors center-headquarters facilities contributed to the high level of patronage (110,000 visitors), with the months of July (16,830), August (22,941), and September (14,446) outdrawing the twelve-month counts of all other SWNM service units, except Frank Pinkley's own Casa Grande. This occurred even though the U.S. Highway 70 paving project stood unfinished. More scholars came to White Sands than at any time since creation of the monument. Prestigious institutions like the University of Michigan sent Dr. Frank Blair, the research associate of L.R. Dice, director of the school's "Laboratory of Vertebrate Genetics" and himself discoverer in 1927 of the dunes' "white mice." Charles B. Lipman, dean of the graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, wanted seeds of plants that grew in the whitest gypsum formations. The University of Chicago's Charles E. Olmsted, an instructor of botany, visited six national parks and monuments of the Southwest that year, and wrote to Tom Charles: "We still feel that . . . White Sands National Monument is more than worthy of its status and preservation." Olmsted "recommended it as something truly unique - both scenically and emotionally," especially the "sunrise and sunset . . . over those strange white dunes against the purple jagged mountains." [61]

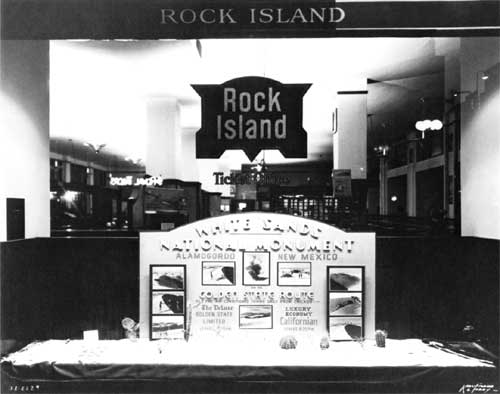

For general public promotion, Tom Charles offered similar access to the monument via correspondence. Mrs. A.F. Quisenberry of El Paso wrote to Charles in March to inform him that FDR's wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, would visit her that month. Charles suggested a circle tour of Carlsbad Caverns and White Sands, promising that "Government officials want to co-operate with you in protecting her visit from over crowded conditions." Theater operators in Albuquerque and Portales wanted sacks of gypsum for use in the lobbies of their movie houses. So did Coe Howard, state representative from Portales, who asked for a truckload of gypsum for New Mexico's exhibit in Amarillo's "Tri-State Fair" (Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma). Tom Charles offered to lend one of the park service trucks for the task. If Frank Pinkley refused, he then remarked: "Possibly I can work my friend the Governor [Tingley] to send a [state] highway truck over with a little sand in it." (Pinkley rejected both options.) Then the Rock Island railroad mounted in the window of its Chicago offices a display of White Sands gypsum as a travel promotion. D.M. Wootton, publicity manager for the Rock Island, noted the prominence of the exhibit in the "Insurance Exchange Building" in the busy Chicago "Loop." Wootton's gesture prompted Charles to exclaim to the NPS's Isabelle Story: "I do not know how I can ever repay my friends . . . for the many nice things they say and do for the Great White Sands." [62]

While scientific research and popular venues had been part of Charles' strategy for promotion of the monument, in 1938 three new concepts appeared: a children's story about the dunes by NPS naturalist Natt Dodge; Charles' efforts to tell the tale of the Spanish conquistador Cabeza de Vaca, and his journey through the Southwestern deserts in the 1530s; and also the custodian's printing and sale of a pamphlet with NPS photographs entitled, "The Story of the Great White Sands." Dodge, who in 1971 would publish the masterful Natural History of White Sands, had visited the dunes in 1938 with his family. The naturalist noted the joy with which his own children frolicked in the gypsum, and wanted to write an article about the annual visits of the state school for the blind. "There is quite a field for exploiting the play angle at the Sands," said Dodge, "simply because, with reasonable control, there is little chance of danger either to the monument or to the people." The dunes offered "the one spot" in the park service "where we can let recreation mean play." In an ironic, if unconscious reference to the resistance of Tom Charles' superiors to acknowledge the pre-eminence of recreation at White Sands, Dodge conceded: "Rolling rocks over cliffs isn't so good in a National Park, so that sort of thing has to be taboo." But the dunes were "unique," and "kids can roll down [them], run races, throw sand, or build castles without harming either the scenery or themselves." [63]

Charles' own writings about the monument had focused upon the recreational potential and natural beauty of southern New Mexico. Yet he also became enamored of the story of Alvar Nunez, Cabeza de Vaca, the shipwrecked Spanish official who wandered from Florida to northern Mexico in the years 1528-1536. The 1930s had witnessed a surge of interest in the historical antecedents of modern America, as much to assuage the doubts of many citizens for the future of the country as to chronicle the past. In particular, the scholarship of Herbert Eugene Bolton, professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley, brought into focus the exploits of the sixteenth century Spanish conquerors in the "Borderlands" (the crescent of land between San Francisco, northern Mexico, and Florida). Bolton's work, and that of his graduate students, evolved as did the fascination with regionalism in architecture that had prompted the park service to design the White Sands visitors center in adobe style.

In the September 1938 issue of New Mexico Magazine, Charles wrote of his speculation that Cabeza de Vaca had traversed the southern edge of the Tularosa basin before turning south for Mexico City. Charles sought to link the explorer with the monument as George Grant had done with Billy the Kid, since White Sands had the only historical museum display in the basin. Such a connection would also bring White Sands into the orbit of the Coronado Cuarto Centennial Commission (or "4C's"), an ambitious project begun in 1934 at the University of New Mexico to commemorate in 1940 the 400 years of Spanish presence in the region since the journey of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado (1540-1542). Governor Tingley, UNM President James F. Zimmerman, and Albuquerque insurance salesman and New Deal official Clinton P. Anderson, sought to place New Mexico on the national tourist map with a series of scholarly and popular events. By 1938 the planning phase of the 4C's had yet to bear financial fruit, but the ever-ambitious Alamogordo chamber of commerce urged Charles to remind the 4C's promoters in the northern part of the state to include venues south of Albuquerque. [64]

Charles' fascination with the Cabeza de Vaca story, like his persistence in supporting establishment of the monument, had worn down the skepticism of others. In January 1937, Joe Bursey, director of the state tourism bureau (and publisher of New Mexico Magazine), had rejected a similar article from Charles because of the far-fetched notion of Vaca's wanderings northward. But Charles read certain passages in Vaca' s journals that described environmental features akin to the basin: the southern edge of the buffalo country; the presence of pinon (pine nuts more common in northern New Mexico); and the general belief among historians that Vaca had to cross the "Llano Estacado" ("staked plains") of west Texas, somewhere north of El Paso. Charles even corresponded with the famed Borderlands historian, Carlos E. Castaneda, the Latin American librarian at the University of Texas, Austin. Castaneda, the proponent of Spanish contributions to a state more enamored of its Anglo accomplishments (most notably the 1836 Texas Revolt and its defense of the Alamo), agreed to help Charles establish the Vaca-Tularosa linkage with access to his own research, entitled, Our Catholic Heritage in Texas. [65]

|

|

Figure 16. Hispanic workers making corbels for

Visitors Center (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

The Vaca story had by late 1938 become more acceptable to park service officials, perhaps because of passage in Congress in November of a $200,000 appropriation to fund 4C's pageants, one of which the organizers hoped to stage at White Sands. Yet Charles encountered strong opposition within the NPS for printing and selling his own literature on the dunes. Tourists for years had asked for some publication giving the essential historical and ecological data of the monument. In November, Charles notified Pinkley that he had shipped to a local printer the text and photographs for his pamphlet. The SWNM superintendent knew that the park service could not stop Charles if he sought no profit from the sale. He also disliked Charles' use of official NPS photographs, including George Grant"s pictures (about half the prints). Pinkley then suggested that Charles contact Dale S. King, NPS naturalist and executive secretary of the newly created "Southwestern Monuments Association." This latter group would publish and distribute literature on the region's park service units, and its fund raising capacity meant that Charles "would be freed of any personal expense" in his promotion of the dunes. [66]

Charles' pamphlet, and the plans for the 4C's, demonstrated the maturing process at work in the monument. Throughout 1938, the NPS pushed to eliminate all remaining "in-holdings" (private claims on monument lands), with closure on the Arizona Chemical Company drilling at Lake Lucero, and the Mal Walters grazing rights in the northeast corner of the monument. Arizona Chemical wanted to mine for "glauberite," a sodium-calcium sulphate, then extract the more valuable sodium compounds. NPS geologist Franklin C. Potter visited Lake Lucero to observe the company's test drilling, and came away satisfied that existing technology made the process unprofitable. He did learn, however, that area merchants sold selenite crystals as tourist souvenirs. Potter worried that the large concentrations of amber-colored selenite at the lake would tempt entrepreneurs; a concern dismissed by Charles, who mentioned the availability of selenite on private land around the monument. Arizona Chemical eventually agreed that sodium production was not feasible at Lake Lucero, but not until they had spent considerable sums for drilling, real estate purchases, and the legal services of Santa Fe's most prominent attorney, Francis C. Wilson (owner of Wilson Oil Company, and the U.S. special attorney for the celebrated 1920s "Pueblo Lands Board" cases). [67]

The Mal Walters lease created somewhat more controversy, in light of the harshness of the Ridinger lease affair. A long-time rancher in the basin, Walters had filed under the 1934 Taylor Grazing Act for 13 sections of public land for his 150-200 head of cattle. He wanted access to seven sections (4,590 acres) of monument land adjoining his ranch; land that he had purchased prior to the creation of White Sands, but for which he had failed to acquire legal title. Tom Charles advised Pinkley that Walters could only graze one cow per 640-acre section of monument property because of its sparse vegetation. Frank Pinkley agreed, telling Washington officials: "As a matter of simple humanity . . . it would appear proper to grant the old man a permit." Herbert Maier, acting director of NPS 's Region Three (now based in Santa Fe), applauded Pinkley's decision, saying: "It is most gratifying to see a letter of this sort come over the desk." Maier saw in Pinkley's action a useful precedent: "It proves that the Park Service is by no means lacking in cooperation with local landowners, and that our superintendents are sympathetic with the principal problems of the local people." [68]

White Sands' search for water proved even more contentious in 1938, as Judge Lawson pressed his claim that the NPS misunderstood his intentions in selling Dog Canyon ranch. In a letter to the Santa Fe regional office, Lawson noted the haste with which park service personnel moved. They had feared the loss of the land and water at such a reasonable rate (Lawson claimed to lose $5,500 in the transaction), which the judge countered with the promise of delivery of the water and retention of the land for sale to another rancher. As for Lawson's failure to pay the state for title to Dog Canyon, the park service realized that it would have to deliver to the state land office an additional $1,250, then invest over $30,000 to start construction of the pipeline. Given the modest accomplishments to date at Garton Lake, despite heavy federal spending, the decline of New Deal programs in the late 1930s, and the delays inherent in a court suit to condemn Dog Canyon, the NPS moved in December to "compel delivery of title." Planning for fiscal year 1940 had already begun, and a lack of water would deter the anticipated rush of visitors to the 4C's programs at the dunes. [69]

|

|

Figure 17. Patrolling the dunes (1930s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |