|

White Sands

Dunes and Dreams: A History of White Sands National Monument Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER FIVE:

BABY BOOM, SUNBELT BOOM, SONIC BOOM: THE DUNES IN THE COLD WAR ERA, 1945-1970

|

|

Figure 44. New Mexico atomic jewelry (1945). (Courtesy Albuquerque Publishing Company, Albuquerque, NM) |

The postwar phenomena of leisure travel and tourism led National Geographic magazine in 1957 to revisit White Sands National Monument to assess the impact of post-World War II visitation. Its editors sent the photojournalist William Belknap, Junior, with his family of four to the dunes to examine the reasons why over one million Americans and foreigners had come to the gypsum deposits in the Tularosa basin. "Enchantment, disbelief, puzzlement" were what Belknap described as "typical questions among startled visitors." His family's response upon entering the Heart of the Sands also represented that of others whom he saw on his visit. His children "shot from the car as if spring-ejected . . . . Then the magic hit Fran and me." As they all raced up the nearest dune in bare feet, Belknap's wife turned to him and said: "I had no idea it could be this beautiful . . . . It's like fairyland." [1]

In that passage the National Geographic summed up the dimension of White Sands that would bless and curse the dunes for a generation after the Second World War. Tom Charles had been proven right: families could not resist the power of the dunes. But recreational use, which had seemed substantial in the hard-pressed 1930s, when local families sought inexpensive entertainment, gave way in the 1950s and 1960s to staggering waves of visitation. Stimulated by forces of economics, politics, military and diplomatic affairs, and social dynamics that changed the nation, the demands upon White Sands testified to the divided mind that Americans would develop about their national park resources. These would also presage the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s that called for preservation to mitigate the excesses of overuse, no matter how benign the intentions of dune visitors.

Three factors after 1945 touched southern New Mexico on a scale and in a form that no one could have predicted. Politically, the nation committed itself to a continued militarization through its diplomatic policy of "containment," an aggressive if ambivalent resistance to the territorial and ideological advancement of the Soviet Union and its Communist form of government. Economically, the massive expenditures of World War II, which poured billions of taxpayer dollars into New Mexico, west Texas, and the western United States, created a boom in science and technology, and also in tourism to release the tensions of a stressful workplace. Socially, pent-up demand during the war resulted in the "baby boom," where returning servicemen and women married, had children in record numbers, purchased houses and household goods, and sparked waves of consumerism that brought highly mobile and large families in their automobiles to White Sands and other scenic attractions in the West. [2]

For White Sands, the triangle of Cold War, military spending, and family recreation caused visitation to multiply exponentially, starting in the spring of 1946. From its low point of 35,000 visitors in 1944, the park saw a doubling within two years, then doubling again in three more years (1949). By 1957, visitation had doubled once more (to 304,000), or ten times the war-era low. From there it did not surprise the staff that visitation exceeded 500,000 in 1965, or that days like Easter Sunday of 1964 had nearly 17,000 paying customers. Park employees noted the growth in attendance each month in matter-of-fact tones, echoing Johnwill Faris's comments of May 1946: "We get little done aside from actual visitor contacts, checking, information, and cleanup of headquarters and the sands." When auto traffic backed out of the entrance station for two miles on the afternoon of Easter Sunday 1964, the staff's reaction echoed their pragmatism in the face of overwhelming demand: they opened the gates and waved in several thousand cars with no attempt to collect admission fees. [3]

|

|

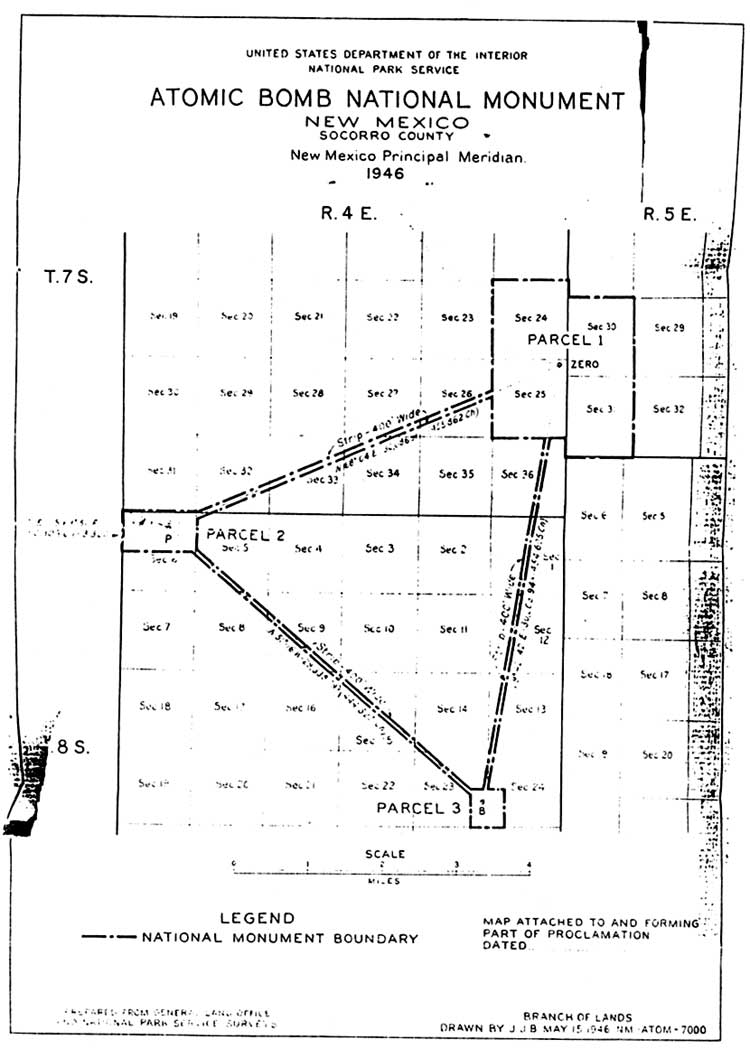

Figure 45. Blueprint for Atomic Bomb National Monument (1945). (Courtesy Rocky Mountain Region, National Archives and Records Administration, Denver, CO) |

The essential feature of facilities maintenance for White Sands in the postwar era was survival. While records do not indicate any formal NPS policy toward the unit, Superintendent Dennis Ditmanson would note sixty years after the park's creation that it hosted twenty times its original visitation with a physical plant built to New Deal specifications. Forrest M. Benson, Junior, who replaced Johnwill Faris in 1961, spoke similar words to his superiors soon after his arrival at the dunes. "We are taking care of 378,000 visitors a year," wrote Benson, who had inherited a park constructed "when travel was approximately 40,000." [4]

The facilities issues confronting superintendents Faris (1939-1961), Forrest Benson (1961-1964), Donald Dayton (1964-1967), and John "Jack" Turney (1967-1973) only worsened as thousands of cars drove over the dunes roads, thousands of campfires burned in the gypsum, thousands of gallons of water were flushed down toilets or poured into overheated car radiators, and thousands of feet crossed the floors of the visitors center and concession. In July 1946, Faris unknowingly foretold the challenge of maintenance when he wrote of his success in locating surplus Army materiel at the closed Deming Army Airfield. The War Assets Administration (WAA) offered to Faris "lumber, pipe, steel plate, warehouse cabinets, filing cabinets, etc." Faris and his rangers made several trips that month from the dunes to Deming (a roundtrip of over 200 miles) to acquire what he called "our 'loot.'" Unfortunately, this continued a precedent first established in the 1930s when White Sands had to rely upon agencies other than the park service for equipment, supplies, and labor. [5]

In order to determine the impact of visitation at the dunes in the early postwar years, Region III Director M.R. Tillotson sent observers from Santa Fe in January 1947 to report on working conditions. Tillotson liked the compact design of the visitors center-headquarters complex, although "the crossing of foot and motor traffic at this tight and sometimes congested intersection [the entrance station] is a constant hazard." The regional director called for an extra "check-in" station, enlargement of office and museum space, more heat for the museum, and development of a "botanical garden" at the visitors center to handle the "numerous . . . questions regarding the identity of local plants." Tillotson found operations at White Sands satisfactory, and could not anticipate the need for substantial changes in the forseeable future. [6]

By the summer of 1947, the growth of travel could no longer serve as an excuse for deteriorating conditions. Johnwill Faris noted the increase in security violations, including speeding, vandalism, and alcohol abuse. The frequency of citations required Faris to negotiate with the justice of the peace in Alamogordo to hear White Sands' misdemeanor cases, and to mete out fines and punishment. The monument also went understaffed for several months that year to save money, as NPS reduced all SWNM units by $10,000. Most galling was the competition for good employees by the neighboring military installations, which did not labor under NPS reductions. Mrs. Tom Charles, operator of the White Sands Service Company, expressed dismay at the wage inflation caused by military spending. "Housemaids can get 75 cents an hour," said the widow of the dunes' first superintendent, "and common labor gets $1 an hour." Thus her efforts to find a clerk for the concession stand to accept $30 for a 40-hour week came to naught, as she found "that experienced service station attendants draw from $60 to $70 per week." [7]

Continued expansion of the two military installations bordering the dunes, plus increased leisure travel, led Johnwill Faris in early 1948 to exclaim: "If January is any indication of what we may expect in '48 woe be unto the White Sands." Profits at the Charles' concession had exploded after 1945, generating from 30 percent to 98 percent return on their investment. The blessings to the Charles' were a curse to Faris, however, and he had to accept more military surplus from Fort Bliss to construct picnic grills from used truck wheels. Drought conditions in the Southwest, which would persist well into the 1950s, further complicated visitor facilities such as picnicking. Toilets ran out of water, sand clogged septic tanks, and the threat of polio throughout the Southwest required expensive garbage disposal away from the public use area. Thus it was no surprise when Faris criticized the regional NPS office in 1952 for refusing to replace White Sands' worn-out road grader. Faris, whose visitation now exceeded 200,000 annually, considered it highly unfair that smaller parks like Wupatki, Sunset Crater, or Chaco Canyon (which averaged less than 40,000 visitors each) should receive new maintenance equipment while White Sands was offered used and inadequate road graders. Regional director John Davis tried to mollify Faris by asking him to give the equipment "an honest trial," and also advised the superintendent "to take this problem in stride without letting it bother you too much." [8]

Water problems, always a concern for the Tularosa basin, entered a new phase with the massive visitation of the early 1950s. Constant trips into Alamogordo wore down the park's tanker truck, which held only 5,000 gallons. This water would then be stored in a wooden tank, which caused problems of algae and bacteria formation. Faris became outraged in January 1953 when the SWNM superintendent withdrew $2,000 from funds to repair the water tank, including use of an automatic chlorinator. "Chlorination of water is a point I cannot conceive of an agency such as ours questioning," said Faris, "particularly here in the Southwest, where contaminated water seems to be the rule, rather than the exception." Even the addition of municipal water from Alamogordo, by way of Holloman AFB, still required chemical treatment. "The visitors ask now why we don't weaken our Clorox with a little water," Faris chided the SWNM, as his staff had to pour bottled chlorine into the tank on hot days to purify the supply. [9]

Shortcomings in facilities would have their counterpart in interpretative services at White Sands in the years after World War II. Promotion of the natural beauty of the dunes occurred via the work of scientists from around the world. Dr. Lora Mangum Shields, professor of biology at New Mexico Highlands University in Las Vegas, brought students annually to the dunes for field trips. Shields and other scholars wrote at length of the riches to be found at White Sands, but the park had no monies to hire a naturalist to explain the dunes to the many visitors who inquired. In like manner, famous photographers like Ansel Adams and Josef Muench came to the dunes to record their striking beauty. Adams had a contract in 1947 with Standard Oil Company to depict White Sands for a promotional calendar which was given free to gas-station customers nationwide. Faris asked the regional office in 1954 for funds to hire staff who could "organize evening talks," prepare a "self-guided tour leaflet," and "make some progress in the promotion of research by other institutions." [10]

|

|

Figure 46. Children playing on V-2 German rocket on

display in dunes (1940S). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

The strain under which White Sands operated by the mid-1950s echoed that of park service units across the country. Demands for improved services and better access to the system's treasures prompted NPS officials to inaugurate a ten-year plan called "Mission 66." Planned to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the park service, Mission 66 began with a system-wide series of "area management studies." The regional team sent to the dunes in 1956 included James Carpenter (administrative officer), Philip Wohlbrandt (engineer), Erik Reed (chief of interpretation), and David Canfield (chief of operations). They produced a lengthy document in January 1957 that explained for the first time the scale and scope of White Sands, and offered suggestions for remedies to the problems that Johnwill Faris and his staff knew so well.

The area management study began by noting White Sands' size (seventh in acreage of the system's 85 monuments). The team identified boundary status problems with the neighboring military bases, and also the heavy volume of local visitation "on special occasions." Among its Mission 66 recommendations were permanent and seasonal employee housing to aid staff in the volatile real-estate market of Alamogordo, and reduction by means of a "diplomatic effort" in the number of "local celebrations." Among these were Play Day and the Fourth of July fireworks; the latter a fire hazard in the heat and crowds of mid-summer (both events were terminated by 1960). The team called for additional full-time staff (a naturalist and museum attendant); extensive repairs to buildings (painting and sealing); steam-cleaning of garbage cans to improve sanitation: and the incorporation of these recommendations within the next three years. [11]

Regional officials in Santa Fe reviewed the White Sands Mission 66 report, but failed to recognize the severity of conditions at the monument. Johnwill Faris spoke bluntly in September 1957 when he learned that the region disagreed with his "justification of our extension of picnic facilities and enlargement of our Visitor Center building." Faris found most annoying the region's "request for brevity," in that he had linked expansion of the physical plant to the increase of visitation. "Whether we like it or not," said Faris, "our area is of the type that is very popular with picnickers." Referring to the review team's study, he reminded his superiors that "according to estimates made during our early years of development, our present unit is ideal for approximately 50,000 visitors per year." Showing little patience with the rhetoric of Mission 66, Faris concluded: "Present inadequacies must be corrected and an expansion program inaugurated, or we will fall increasingly short of our Service goal with the passing years." [12]

Johnwill Faris' confrontation with his superiors reached a critical stage in 1960, after fifteen years of explosive growth at the monument. In his 22nd year at White Sands (21 as superintendent), Faris had labored under the strain of visitation, environment, and NPS management to make the dunes become a professional and respected unit of the park service. The strain showed, however, when George Medlicott of the regional office filed a "Master Plan for the Preservation and Use of White Sands National Monument." For Medlicott, the central feature of White Sands' planning was alleviation of the crush of vehicles at the entrance station, immediately west of the visitors center. Over 100,000 cars passed through the narrow two-lane portal, at a rate estimated at one car every 50 seconds during operating hours. Faris had been asked by Mission 66 planners four years earlier to predict visitation for the next two decades, and believed that the figure of 1.3 million was "not very far off . . . and will be reached and passed by 1975." Medlicott, while not using that number, nonetheless told NPS officials that access, parking, residential housing, and utilities all needed upgrading and expansion to meet whatever visitation increases that Mission 66 scenarios would require. [13]

Publicly, Johnwill Faris spoke optimistically that year of the benefits to accrue to White Sands from Mission 66 work. In May he wrote for the regional office's monthly report: "Our first taste of this marvelous program has been the awarding of contracts for 40 new shades and tables, as well as 56 new garbage disposal units, and the same number of fireplaces." The concession business would also benefit from these facilities, even though the Tom Charles family had sold their interest in 1954 to Robert Koonce of Alamogordo. Koonce tried to maintain the level of service demanded by the visitors, but found the task overwhelming. In 1960 he in turn sold the concession to local businessman G. Clyde Hammett, who offered to invest $40,000 in a new facility separate from monument headquarters. Hammett, who also anticipated strong sales volume from the Mission 66 program, led Faris to report: "We can expect much greater service with the expansion of facilities that is planned." [14]

What Faris did not say about Mission 66 was that NPS superiors had decided not only not to expand along the lines of the master plan. They also revived old arguments from the days of Tom Charles first as custodian, then concessionaire, to dispute the findings of Medlicott and Faris. Sanford Hill, chief of the division of design and construction for the NPS western office in San Francisco, informed the regional director in April 1961 that the problem at White Sands was the character, not the volume, of visitation. "It appears that the concession is mainly used by local people who come to the Monument as a substitute for a city park," said Hill. "This local use in turn," he continued, "has created the traffic problems which now exist." Hill believed that "rather than giving further encouragement to such use by expanding concession facilities," the NPS should "consider the possibility of eliminating the concession entirely and simply installing soft-drink machines." Hill further blamed the Charles family for the expansionist mentality in the area, saying that the park service had to "accommodate" them with the concession contract. Now that the family had left the business, said Hill, "we are apparently relieved of our obligation to retain a concession for their benefit." This would negate any need for a state highway interchange at the entrance (which would be charged to the NPS), and would also inhibit the ambitions of Clyde Hammett, whom Hill suspected of being "interested primarily in developing a saleable [concession] facility." [15]

One could hear in Sanford Hill's memorandum the voice of Frank Pinkley and other NPS officials who had despaired of the intense localism surrounding White Sands at its creation. Ironically, Hill gave no credit to Johnwill Faris for laboring for 22 years to professionalize the monument in the face of great odds. That same year as the master plan appeared, Faris suffered a severe kidney infection that required major surgery in El Paso, and a lengthy recovery period in late 1960. NPS officials then discussed with Faris (now a 34-year veteran of the service) the need to provide White Sands with new management. Faris and his wife, Lena, would leave in January 1961 for Platt National Park, a small unit in southeastern Oklahoma, where he would remain two years as superintendent before retirement. [16]

Faris' departure marked the end of an era at White Sands; the period of creation and development of one of the most visible monuments in the park service system. Sanford Hill notwithstanding, this process owed much to the attention paid by Charles and Faris to local interests. These in turn rewarded Faris with a good life as a prominent community member. Donald Dayton, White Sands superintendent in the mid-1960s, recalled that static conditions within NPS management in the 1950s had kept Faris from advancing his career by moving to a larger park. Yet Lena Faris, remembering their life at the dunes from a mother's perspective, noted that the stability permitted their sons James and Kenneth to graduate from the local public schools, and to have many lifelong friends in Alamogordo. Johnwill served in 1950 as president of the local chamber of commerce, which in January 1961 held a luncheon attended by over 100 guests in honor of himself and his wife. There the grateful citizenry recognized Johnwill's and Lena's work in "Rainbow, DeMolay, Chamber of Commerce, PTA and other civic functions," and gave Johnwill a life membership in the chamber. He would also return in 1963 to serve two years as its executive director upon retirement from Platt. The best testimonial to Faris' local prominence, however, came in March 1961 when his successor at White Sands, Forrest Benson, wrote to regional officials: "[Faris] apparently knew everyone personally in the surrounding counties, and this presents quite a challenge to continue this fine community relationship." [17]

|

|

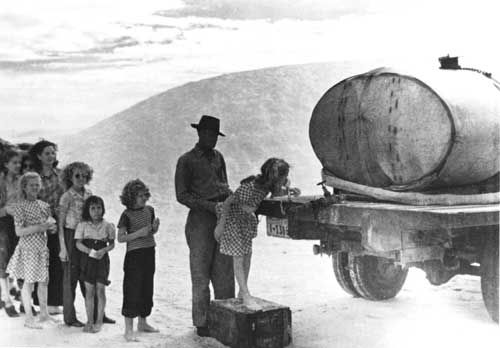

Figure 47. Summer picnickers (1950s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

Forrest Benson took over White Sands as a new generation of Americans came to the park service's units. Known to sociologists as the "baby boomers," these families of postwar prosperity had children of teenaged years who would bring new pressures to bear on the dunes. Among the visitation issues facing Benson, Don Dayton, and Jack Turney in the 1960s were increasing vandalism, police patrols, arrests, the use of alcohol, and potential gang violence; all consequences of the rebelliousness of youth multiplied by the millions of children born since 1945 and coming to maturity in the 1960s.

The first feature of Sixties life to touch White Sands was the demand by visitors for campground facilities, preferably in the heart of the dunes. Local officials had complained to Forrest Benson as early as April 1961 of the "lack of Mission 66 development in this area." Picnics were not enough for many families visiting the area, as tourists often came west to sleep outdoors in the scenic beauty of the region. This also reduced the costs of travel, and prompted U.S. Senator Edwin L. Mechem, an Alamogordo native who as a boy had camped overnight at the dunes, to write NPS director Hillory Tolson: "This Monument is beautiful and restful at night. I would suggest that you spend a night there sometime." Tolson responded to Mechem by noting the reasons for prior refusal of camping at White Sands ("adverse environmental conditions, lack of sufficient potable water, and because good camping facilities are available nearby"), but did solicit an opinion from White Sands personnel. Leslie Arnberger, acting regional director, informed NPS officials in Washington that camping at the dunes emanated from "a growing desire to be privileged to experience a moonlight night in this vast white wilderness." Unfortunately, initial construction costs for a 50-unit campground in the dunes would exceed $300,000, while facilities maintenance would add $25,000 annually, and night patrols another $30,000. [18]

These costs notwithstanding, the calls for camping at White Sands persisted. Visitors seeking overnight accommodations were allowed to park outside the monument entrance, and to use its restrooms in the morning. By 1964, the park had begun a new master plan under the aegis of the NPS' "Road to the Future" program. Sanford Hill returned to the dunes in August of that year to examine the utility of Garton Lake as a campsite. Since the early 1960s, officials from the state of New Mexico, the city of Alamogordo, and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) had inquired about the recreational potential of the lake. Hill, who in 1960 had blamed local interests for despoiling the White Sands experience, now recommended campgrounds at the lake or near the visitors center (for easier crowd control) . He disliked the dunes as a camping location because of the cost of services and patrols. Acknowledging this was a change of heart for Hill, who considered White Sands a "Class IV, Outstanding Natural Areas" site. Development of such locations, said Hill, should be "limited to the minimum required for public enjoyment, health, safety, and protection of the features." Hill preferred that White Sands "should hold the line strongly against expansion of present facilities or introduction of new adverse activities." [19]

The second aspect of visitation in need of improvement in the 1960s was interpretative services. Whereas the 1930s focused upon museum construction, the 1950s on nature trails and hikes, the 1960s brought an international audience to the dunes among the hundreds of thousands of annual visitors. Acting superintendent Hugh Beattie noted in September 1964 that "at least 500 visitors received information about White Sands by listening to tape recorded talks in German, Spanish, French, Japanese, and Italian." The multilingual staffs at Holloman AFB and WSMR produced these tapes, as they hosted such groups as "the foreign student battalions from Fort Bliss [German and Japanese]." Spanish-language materials were necessary because "family groups from Chihuahua have requested such help frequently." Stimulating the improvement of this program were complaints by native speakers of these languages, like the German linguist from "the Foreign Service Institute of the [U.S.] Department of State." She had informed monument staff in July 1964 of the "poor voice quality, articulation, and content" of the German tapes at the visitors center. "We believe that the appeal of our foreign language program," said Beattie, "justifies further development and upgrading of the presentation." The desire to meet the needs of well-educated foreign visitors thus led Beattie to request funds for the translations into over one-half dozen languages. [20]

|

|

Figure 48. Women golfers (1950s). Note dark-colored

golf balls. (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

Most troubling of the "baby boom" changes at White Sands was the need to improve law enforcement at the park. This phenomenon had touched all NPS units, as it had the nation as a whole, in the 1960s because of the rate of youthful violence in America's urban centers. Rebellion was a feature of Sixties life, fed by such movements as civil rights, antiwar protest, campus unrest, and the drug culture. Superintendents' reports for White Sands show the progression of law enforcement issues from the early 1960s, when speeding, littering, and an occasional fist fight took place, to the decade's end when drunkenness, burning of picnic tables, firing of bullets into monument signs, theft of property, and gang fights prevailed. Don Dayton revealed the severity of such incidents in 1966 when he informed the Southwest regional director: "The subject state law was never enforced here previously . . . . Over the years this has tended to make White Sands the logical place to hold beer parties that were prohibited elsewhere." This led Dayton to stop the use of alcohol at the dunes, with both the usual complaints and the decline of vandalism and violence. Dayton also had to close the park at 10:00PM in the summer, and to implement higher fees to meet increased costs of service to the public. Among those services was an experiment for a few years with a mounted horse patrol for visibility and speed of response. [21]

|

|

Figure 49. Crumbling adobe at Visitors Center in

need of repair (1950s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

Lost amid the press of daily business at the dunes was the effort of White Sands' staff to improve access to scientists and researchers. This included assisting NPS naturalist Natt Dodge with research on his pathbreaking Natural History of White Sands (1971) and the international studies of Edwin McKee, a USGS official from Denver, on dunes and their movement. McKee's work required cutting across dunes with large earthmovers borrowed from the military, along with constant measurement of dune drifting and reformation across the monument. McKee's and Dodge's research coincided with the ecological emphasis of the 1960s environmental movement, and the call by Interior secretary Stewart Udall for more analysis of the natural resources in the nation's park system (the "Leopold Report"). Unfortunately, the monument staff could not accommodate all requests for access to the dunes' resources. In August 1965, a group of Mescalero Apaches came to the park in search of "mint bush" for use in ancient tribal ceremonies. The staff told the former inhabitants of the Tularosa basin that "all flora is protected in the monument," and the shrubbery they had collected was confiscated. [22]

Intrusions by Mescalero medicine people, while in violation of NPS rules, would prove to be mere trifles compared to the generation of military encroachment onto the dunes. If the baby boom and postwar economic expansion triggered the exponential growth of White Sands visitation, so too did the quest for national security press upon the monument's borders like no other park service unit. By studying the relationship between the Department of Defense, represented by Fort Bliss, White Sands Missile Range (WSMR), and Holloman Air Force Base (HAFB), one learns several lessons about the park service and Cold War America. The massive expenditures of federal defense dollars ($150 billion in the West from 1945-1960), in the words of Gerald Nash, "opened up a vast new resource for jobs." Ironically, said Nash, "technology made great stretches of the once vaunted Great American Desert habitable and pleasant." But the wealth and prosperity generated by "vast new scientific and technological centers . . . with special emphasis on the aerospace and electronics industries," which caused western income to more than double after 1945, also placed great strains upon the ecology and natural resources of the Tularosa basin. While Alamogordo never became the city of 90,000 that Johnwill Faris predicted in 1956, the dunes could serve as a case study of Nash's charge in 1977: "By the middle of the twentieth century the West had already become an almost classic example of environmental imbalance brought about by wanton and unplanned applications of science and technology." [23]

|

|

Figure 50. Ranger checking stream gauge in Dog Canyon (1950s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

Johnwill Faris' predictions about the relationship between the armed forces and his monument were more accurate than his guesses about local population growth. As early as January 30, 1946, he wrote to the regional director that "the [Alamogordo Army Air Base] will be manned by a skeleton crew merely as a plane refueling station, emergency landings, etc." As for the proving grounds to the west and south, "[it] seems to be going stronger so we are yet in the middle of excitement." What had prompted the WSPG activity was the capture in Europe by Allied forces of German V-2 rockets; the same weapons that had proven so effective in Adolf Hitler's bombing of London during the Battle of Britain. The Army wished to examine these V-2's for their accuracy and firepower, but needed more open space than the Aberdeen, Maryland proving grounds would permit. Without knowing it, Faris identified the most telling feature of the next 25 years at the dunes when he reported to regional headquarters of a visit from a WSPG executive officer, "Major Holmes." He had come to the park in late May 1946 because an early V-2 test had gone off course and crashed into the dunes. While Holmes denied any problem with the test, said Faris, "a general visiting here, who has been in charge of similar tests in Florida, informed me, unofficially of course . . . that . . . [the Army] themselves have little or no idea where the projectile might land." [24]

The rationale for testing of missiles in the Tularosa basin sprang from diplomatic and economic forces far beyond White Sands. Successful development of the atomic bomb in southern New Mexico had shown the military the advantages of the region's open space, sparse population, and pliant civic leadership. Victory in Europe and the Pacific theatres resulted from massive applications of air power, which the armed forces sought to maximize in the first years after the war. Then the burgeoning confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union provided more incentive for escalation of advanced-technology weapons research and testing. When one added the financial windfall of postwar defense spending, it was little surprise when Johnwill Faris learned in January 1947 of Army plans to consolidate air bases in Kansas and Utah at Holloman. [25]

Construction of test facilities throughout the basin began soon after the visit to the monument by President Truman's "Strategic Bombing Survey" team. Its members included Paul Nitze, who would become famous as an arms negotiator for the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, and Franklin D'Olier of the Prudential Insurance Company, identified by Faris as "a long time personal friend of former [NPS] Director Horace M. Albright." The survey team negotiated the first of several "joint-use" memoranda of understanding (MOU's) between the Army and the park service over access to the western sector of the monument. The NPS believed that "this permit will not remain in effect over six months," and that "upon completion of the tests all materials shall be removed by the War Department." The Army erected a series of ten to fifteen towers, 30 feet in height and ten feet wide, to carry electric transmission lines from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's hydroelectric power plant at Elephant Butte Dam. The Army offered to sell White Sands some of its electricity for the "very nominal" sum of .015 cents per kilowatt hour; a bargain compared to the monument's oil-fired electric plant. The military also explored the option of outright purchase of the Dog Canyon stream flow, which Faris described in 1947 as producing "65,000 gallons daily, an amount far in excess of monument needs now or for years to come." [26]

Hindsight reveals either the naivete of park service officials, or their sense of inadequacy in the face of national security imperatives in the years prior to the war in Korea (1950-1953). In March 1947, Superintendent Faris reported a meeting with the WSPG commander, who was "very liberal with his information regarding appropriations, proposed construction, rocket firings and type of missiles, probable effects on our area, etc." What shocked Faris was the commander's assertion "that negotiations were in progress at the present time whereby . . . Naval activities would virtually close down our area." The rationale he gave for this sweeping and secretive land transaction was that "seemingly no known controls exist for the rockets to be fired." Then, in a statement remarkable for its candor, Faris observed: "The bulk of the information we have gathered would indicate that we [White Sands] are just an existing evil, and not necessarily to be considered by such high priority agencies as the War and Navy Departments." [27]

Such arrogance would manifest itself in a thousand ways to Johnwill Faris and his successors. Two incidents in the summer of 1947 typified this mindset of military haste and shortsightedness. That July, in the early stages of a ten-year drought, the Army expropriated several water wells near the monument to supply its missile range. "The nature of this water," said Faris, "was such that lately we are forced to haul almost entirely from Alamogordo." More disturbing to the superintendent was the behavior of a "Sergeant Ross," who came to the dunes on June 29 with his wife and another couple. Ross did not wear his military uniform, and thus had to pay the 50-cent entrance fee like any other visitor. The sergeant declared his immunity from any park service charge, and drove toward the dunes, where Faris jumped on the running board of Ross' car to stop him. When Faris reached into his shirt pocket for a notebook, Ross ripped the pocket open, seized the notebook, tore it to shreds, and warned Faris that he "and our whole area would be 'blown to Hell' if I reported the case." Upon complaint filed with Ross' superiors, the Army asked Faris not to press charges if Ross were prohibited from returning to the dunes. The superintendent relented, not wishing to expose Ross to a court-martial, and concluded: "I believe the action taken certainly made it clear that such incidents would not be tolerated and I dare say the entire camp [WSMR] knows by now that bluffs and threats do not scare us one bit." [28]

Sergeant Ross' comment about "blowing" the monument "to Hell" had a faint ring of truth to it. As tensions escalated worldwide between the client states of the Soviets and Americans, weapons testing grew more frantic. By August 1947, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, through their district office in Albuquerque, had drawn a map of the Tularosa basin in which White Sands National Monument would be surrounded by the missile range. The Engineers' property division had "acquired the fee simple title to all private owned lands within the Fort Bliss Anti-Aircraft Range, has the exclusive use of all private lands and interests within the Alamogordo Bombing Range until 1967, and co-use of all other private lands and interests within the area for the duration of the National Emergency and six months thereafter." Secretary of War Kenneth C. Royall thus wrote to Julius Krug, Secretary of the Interior, to explain the need for all public domain acreage in the basin not already covered by permit. Royall also wanted a twenty-year (not six-month) extension of his department's co-use MOU with White Sands. The secretary believed that no public hearing was needed on this massive land transfer, since "the area in question, except for the proposed extension to the north, has been used by the War Department for several years." Royall would, however, send representatives to such a hearing if Krug considered this "necessary." [29]

Johnwill Faris and his staff thus faced a turning point in park service relations with the military. The 1946 MOU was ignored with impunity, as shells dropped on the monument with increasing frequency (one in December 1948 left fragments "the size of a desk top" one-quarter mile from the residential compound). Then for the first time in September 1947, Faris learned why the dunes had to be included in the test firings. Colonel Pitcher of the WSPG came to the park to inform Faris of the status of the land acquisitions, and to explain why the Army had built another utility line across White Sands without NPS permission. "They mentioned the fact that it would mess up certain calculations" if missiles could not travel north to south in the basin; "all of which," said Faris, "may or may not be true." The superintendent, as he would do so often for the next decade, "clearly stated . . . that the same Congress . . . that charged them with protection of our country, charged us with keeping that portion of the country within our boundaries in as near the natural state as possible and that we were as intent in duty as I appreciated they were in theirs." [30]

Matters involving monument trespass reached a peak on August 2, 1948, when the Army held a public hearing in Las Cruces to declare their intentions for the Ordcit Project. Other affected federal agencies joined the NPS to hear what the Army had in mind. Hillory Tolson, now acting NPS director, wrote to his counterpart at the BLM to inform that agency of the park service's position on Ordcit. "A 'permanent' permit is out of the question," said Tolson, "since it would amount to virtual disestablishment of the monument." John K. Davis, acting regional director, also wanted NPS officials to protest the newest technique in missile recovery work at the monument: "a close gridiron pattern traversed with many jeeps." Davis called this an "apparent disregard or noncompliance" with the MOU, and he wanted other federal agencies to hear in public the extent of military intrusion into the fragile ecology of the basin. [31]

At the Las Cruces meeting, the unified opposition of local stock raisers and federal land agencies forced the Army to soften its demands for the Tularosa basin. So many ranchers spoke that the Army held a separate hearing for federal officials on August 4, where Johnwill Faris and other regional staff detailed their grievances. One complaint in particular was the arbitrary firing schedule, which Faris noted could come at 4:00 in the morning. "You can't call your time your own," Faris told his superiors, "[and] consequently, we have to be on the alert for the Army practically all the time." Milton McColm, chief of lands for the Southwest region, came away relieved at the Army's willingness to listen, and concluded: "No doubt there will result less restrictive operation of other than Army use and interest." [32]

Over the next twelve months the dialogue continued about military usage of basin lands. Rumors flew among stock raisers, such as the permanent closing of U.S. Highway 70 once the Ordcit land transfers became official. Fueling speculation about the Army's intentions was an article appearing in the February 25, 1950 issue of the Chicago Tribune, entitled "Strange Rocket Security Modes Govern Range." The author, Hal Foust, reported that all Tularosa basin military installations had an "apparent jumpiness" which he related to disclosure of the sale of atomic weapons plans by Klaus Fuchs of the Los Alamos scientific laboratory. Fuchs in 1945 had transferred secret documents to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in a house near downtown Albuquerque. The public only became aware of this breach of national security four years later, when Soviet scientists and engineers successfully tested their own atomic device. Eager to learn about security conditions at the "site of continuing secret preparations for warfare of long range missiles," Foust came to Alamogordo to visit the two military bases. He marveled at the furtive behavior of supervisory personnel, the diffidence of low-level sentries at the gates to WSPG, and the candor of local business people to inform a reporter what they had been told about rocket firings. Convincing Foust of the bizarre nature of the Cold War in the New Mexican desert was the reaction of Johnwill Faris: "If we vacated every time the army tells us we are supposed to . . ., we wouldn't be performing our duty to the national park service as guardian of these properties, including our museum, and as host to tourists." [33]

Military imperatives prevailed over local concerns when on April 1, 1949, the Army and park service drafted a new permit for joint use of White Sands. The MOU declared that "physical use of the monument is not desired by the Armed Services," and that 24 hours' notice of evacuation would be given prior to test firings. NPS staff would be compensated for overnight removal, and the park would be reimbursed for restoration of any lands and facilities damaged either by missile impacts or recovery crews. Similar considerations would be extended to private grazing leaseholders within the monument. A third category of reimbursement would be for the concessionaire at the dunes, "to compensate him for any losses or damage sustained that are attributable to [the Defense] Department's activities." [34]

This new agreement, coupled with the escalation of the "arms race" with the Soviets, propelled White Sands into its second phase of postwar relations with the military: that of dependency upon military largesse. In November 1949, Faris reported to the regional office: "I hope our Service can see the handwriting on the wall as indicated by all this Army expansion on both sides of us." The superintendent had learned that there were "over 500 homes under contract within 35 miles of White Sands," which he also interpreted to "mean that we will have to furnish recreational facilities to a large number of these families." A year later (October 1950), the superintendent recorded more growth: "Some 2,500 new housing units are proposed by the Army alone within a radius of 125 miles of the White Sands." The Army in addition came onto the monument to conduct a thorough survey of the NPS boundaries, and also to research the legal titles of the private in-holdings of local ranchers. [35]

Factors of military expansion and economic growth in the early 1950s encountered a third reality in the Tularosa basin: the availability of water. Temporary status for Holloman AFB and WSPG had limited the military's use of the area's scarce resources, while White Sands had learned through experience the value of water conservation. The new generation of weapons, facilities, and personnel coming to the basin, however, required large volumes of water for industrial, commercial, and residential use. This pattern echoed the boom growth in other Southwestern communities from Los Angeles to Dallas, and resulted in calls for expensive water resource development to mimic the humid-climate conditions preferred by military bases elsewhere.

Compounding this dilemma of water for White Sands was the lengthening of the drought cycle. In January 1951, Johnwill Faris reported ominously: "Already our Sands well is drained at a single pumping . . . This has not occurred before in our history, especially this time of year." Dog Canyon's streamflow was of little help, and Faris described it "as low as has ever been recorded." NPS officials came to the dunes to negotiate with the Air Force for access to its water line from Alamogordo, acquiring 300,000 gallons per month (10,000 gallons per day) for the monument. They had found deplorable the fact that "there are practically no water-using facilities for the public . . . and that only three of the proposed eight employees' quarters have been provided" with running water. A. van Dunn, chief of the NPS water resources branch, noted that White Sands had few options other than to accept the Air Force's offer, and that national emergencies could permit Holloman AFB to terminate all water deliveries with only a 30-day notice. [36]

This latter issue bothered NPS officials enough to conduct one last survey of a pipeline to the White Sands' water source in Dog Canyon. In March 1951, acting NPS director A.E. Demaray warned regional officials of the tenuous nature of the Air Force offer. "We realize how badly an adequate supply of water is needed," said Demaray, but worried about the cost of the Holloman pipeline should the agreement be terminated. "The assurance of permanence and adequacy of water supply are dominant factors," Demaray concluded, and he promised to support a Dog Canyon system despite its "great first cost and delay." Demaray's enthusiasm for Dog Canyon faded, however, when regional director Tillotson informed him two months later: "We estimate that a water system with supply direct from Dog Canyon would cost $150,000, or $90,000 more than from the Air Base." Sealing the "bargain" for the NPS was news that the 1952 defense appropriation bill contained $8 million for utilities work at Holloman, including a ten-inch pipeline from the city of Alamogordo's two-million gallon storage reservoir. Merritt Barton, regional NPS counsel, noted that water sales to Holloman provided the city with substantial income, and more importantly: "There is a civic pride in White Sands, and the resulting desire to facilitate its public use." Barton believed that this would expedite the sale of water to the monument at favorable rates, even in the unlikely event that Holloman AFB would be abandoned. [37]

|

|

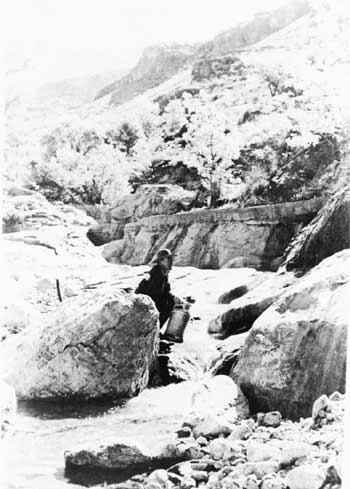

Figure 51. Scarcity of water in dunes required use

of aging tanker trucks (1950s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

The permanence of military intrusions into the dunes led Luis Gastellum, assistant SWNM superintendent, to visit White Sands in March 1953 to discuss relations with the Air Force. Gastellum reported finding "no evidence of lack of cooperation on the part of officials in authority." He blamed the incidents instead on "military personnel who have failed to follow instructions of their own superiors." The SWNM official conceded that Johnwill Faris might be "annoyed by these problems, but they are problems which are apt to develop in any area where this type of experimentation is taking place." Gastellum failed to identify other park service units undergoing similar "experimentation," and instead told Faris to consider giving "a series of talks at [HAFB and WSPG] as a part of the orientation program for new personnel." Faris, more knowledgeable of local conditions, informed his superior that "the personnel turnover is so great that little good would be accomplished for the effort he [Faris] would have to put out." Gastellum did suggest billing the military bases for time and energy spent on missile recovery, but he concluded rather naively: "Until we have better reasons and some specific facts to present, I see no reason for representatives of this office to attempt to obtain a better understanding of our problem." [38]

Gastellum's ignorance of life at White Sands fit the pattern first detected in the 1930s by Tom Charles in his discussions with regional and national NPS officials. The year 1954 provided several incidents of military thoughtlessness that Gastellum unfortunately did not witness. A "Mr. Michelman" had come to the dunes in January, entered the picnic area, and lay down atop a dune to rest. A "scouting plane" from one of the military bases came in low in search of missile fragments and struck Michelman. The hapless victim lost his elbow joint, and contracted a case of yellow jaundice, which required several weeks' hospitalization in El Paso. Equally terrifying was the accident in May 1954, when an errant (Faris called it "misguided") missile crashed into the picnic grounds. The collision destroyed a picnic table, benches, and shelter. Faris noted dryly in his monthly report: "There was no adverse publicity given to the incident for which we are very thankful." Finally, a park service official from San Francisco came to the dunes in 1956 and noted the chaos attendant to military intrusion. Charles E. Krueger, NPS landscape architect, reported on the inadequacy of the physical plant for the volume of visitation, then spoke of a "graphic illustration of some of the operational problems confronting the superintendent." A warhead had separated from a missile, and crashed near the visitors center. "A helicopter landed and took off in front of the headquarters building," said Krueger, "light planes were landing and taking off on the highway and heavy trucks, automobiles, jeeps, etc., were scurrying all around the area." In a laconic understatement, the landscape architect admitted: "While it was an exciting piece of business to watch, it was hardly the atmosphere we normally associate with a National Monument." [39]

As the decade of the 1950s closed, the military's role in basin affairs became more entrenched. By 1957, Johnwill Faris would report that the armed services sought "designation of over 100 square miles [40 percent] of the Monument as a '20-30 mile impact area." The Army had also carved across park service land the route to the infamous "instrumentation station NE-30," again "without consent of the [NPS] and in most instances without its knowledge." The Holloman commander then sought access to "sections 6, 7, and 18 [Township 17 South], [Range 8 East]," for use as a "ground launch area." Fred Seaton, secretary of the Interior, wrote to Defense secretary Charles E. Wilson that month that the military's desire for "unlimited physical use of the Monument" negated NPS plans for Mission 66 expansion. The issue of unrestricted access caught the attention of Bruce M. Kilgore, editor of the privately published National Parks Magazine. Kilgore and his National Parks Association conceded that "when a matter of national security is involved, even our wonderful system of national parks and monuments may have to give way." But the editor, who considered himself one of many "sincere Americans," also held that "the convenience of the Army is not sufficient excuse for allowing our already diminishing heritage of national parks and monuments to be used for military target and testing purposes." Kilgore asked Secretary Seaton to apprise his "100,000 members and others over the country who read our magazine" about the status of military intrusion at White Sands, and admonished further: "Be very hesitant in allowing any unproven claims by military agencies to serve as justification for loss of part or all of the White Sands National Monument." [40]

Seaton's response to Kilgore reflected the temper of the times: the continuation of the Cold War, the shadow of the anticommunist mentality known as "McCarthyism," and the presence in the White House of the former Supreme Allied Commander in World War II (Dwight D. Eisenhower). The Interior secretary outlined the "modest" beginnings of missile impacts in the 1940s and early 1950s, only to be superseded by "great technological advancements." Negotiations between Defense and Interior always resulted in the latter giving way, and in the recent case, said Seaton: ""It appears that, in the interest of national defense, it would not be practicable . . . to impede or prevent reasonable continued activity of the guided missile program." The secretary promised Kilgore's readers: "You are assured that this unusual development will not act as a precedent in other cases and we are aware of none like it." Seaton had not known of Luis Gastellum's admonition in 1953 to Johnwill Faris about the the frequency of military incursions onto park lands, and hence his conclusion: "It is hoped that the above explanation will satisfy you that we have agreed to the least possible intrusion . . . in admittedly adverse circumstances." [41]

Johnwill Faris' last two years at White Sands (1959-1960) were not a crowning achievement in his three-plus decades of service to the nation's parks. While his kidney failure may have forced his transfer to the quieter Platt National Park, the rush of military activity at decade's end disheartened him greatly. In June 1959, a Nike rocket, capable of carrying a nuclear warhead over 1,000 miles, landed off course near the heart of the dunes. Recovery crews from the missile range informed Faris "that the Nike contained classified material, which would necessitate its immediate destruction." The nose of the missile rested in several feet of water, making recovery costly if pumps were brought in. The recovery team decided to explode the missile with 500 pounds of TNT, driving it 18 feet deep into the gypsum. "Investigation after the blast," reported an anguished Faris, "almost gave me heart failure." The explosion created "a gaping crater full of black water, and an area with a radius of about 300 yards was as black as coal." Faris declared that he was "sick at the sight of it, and vowed never again would we allow any such disposal of fallen missiles." [42]

Late in 1959, Faris noted the dependency of the Tularosa basin on the military activities that disrupted life at White Sands. He could not recruit a teller to handle the monument's cash receipts because "we are too close to big defense installations to make our GS-3 [job classification] very attractive." Yet the declining American economy had also touched southern New Mexico, resulting in reduced visitation. "Rumors of a cutback in contracts" at Holloman, said Faris, "are not inducive to free spending." Then in January 1960, Faris went on patrol near Lake Lucero, only to discover "considerable construction by the Army along the right-of-way we granted them on our western boundary." Faris was "somewhat amazed at the intensity of the repairs." He also reported: "An infraction of our agreement occurred again in the vicinity of the lake, but we have been assured of its being corrected." [43]

|

|

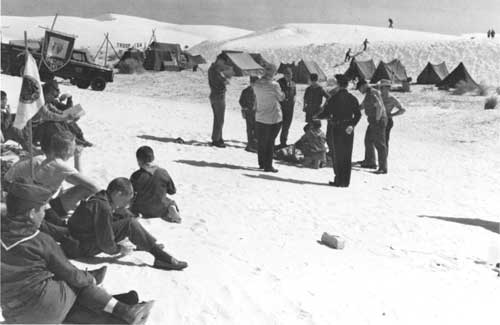

Figure 52. Boy Scout Jamboree in the dunes (1960s). (Courtesy White Sands National Monument) |

Johnwill Faris' departure from White Sands coincided with the escalation of another series of military programs under the aegis of President John F. Kennedy's "New Frontier." The young Democratic senator from Massachusetts had campaigned in 1960 against the perceived drift of the nation under the leadership of the grandfatherly Eisenhower. Kennedy vowed to "get the country moving again" through an economic stimulus package that, in the words of historian Walter McDougall, "galvanized science, industry, and government." The 43-year old president proposed a two-track economic and security strategy of peaceful space research and advanced weapons testing. "The Apollo moon program was at the time the greatest open-ended peacetime commitment by Congress in history," said McDougall, while "the Kennedy missile program was the greatest peacetime military buildup." White Sands, unlike its peers in the park service, would thus witness yet another wave of change, given its location in the desert Southwest that offered the Defense Department and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) an environment that McDougall termed "limitless space, limitless opportunity, limitless challenge." [44]

The first White Sands official to encounter JFK's promise to put a man on the moon within a decade was Forrest M. Benson, Junior, most recently the superintendent at Chiricahua National Monument in southern Arizona. Benson's prior postings had made him familiar with the arid ecology of White Sands, but nothing could have prepared him for the dunes' role as a staging area for New Frontier science and engineering. In March 1961, Benson went on his first boundary patrol, only to be "amazed at the amount of [defense] installation." One example of such "encroachment," as the park service now called it, came the next month when Benson discovered that "a 58-wire telephone line and road traverse the Monument for approximately 1 1/2 miles." Then Benson read in the Albuquerque Journal on September 17: "Army engineers said Saturday they had found a potential spaceport on a huge dry lake bed within the confines of the White Sands Missile Range." Michael L. Womack, chief of engineering for the Albuquerque District of the Army Corps of Engineers, reported that the area (Alkali Flats) would cover 70 square miles, and would be "capable of supporting space craft landings, such as the Soviets claim they have accomplished." [45]

Kennedy's highly touted "space race" had thus come to White Sands, touching not only the dunes but Benson's future career in the park service. The superintendent visited with the WSMR commander, General John Shinkle, to gauge the pace of testing and encroachment. Then on October 30, John E. Kell, Southwest regional chief of lands, joined Benson and officers from the missile range and air base to examine the "load bearing" tests being conducted along White Sands' northern boundary. Kell and Benson learned that the armed forces were working on the "Dyna-Soar" project, a high-speed, high-altitude aircraft that needed long runways for reentry from space. Military officials gave three reasons for use of Alkali Flats, and extension of runways into the dunes for five to six miles. The WSMR had already installed "numerous very accurate 'tracking' and instrumentation stations interconnected with a central control system." In addition, the Dyna-Soar plane needed to land on skids on the salt flats because "no tires are currently available that will stand the heavy pressures and heat of landings." Finally, said Kell, Dyna-Soar pilots would find "the visibility of the white sands as a target area easily discernible from outer space while . . . in orbit." The military officials told an impressed Kell: "If a person was on the moon the White Sands area would be clearly visible from that distance [250,000 miles from earth]." [46]

The Dyna-Soar project as planned did not come to fruition (it would become the "Space Transportation System," or "space shuttle," of the 1980s), but this did not spare White Sands. Conventional weapons testing continued at the WSMR and Holloman in the early 1960s, along with the enthusiasm generated by the first manned spacecraft to orbit the earth (the "Gemini" program), and Kennedy's vaunted "Apollo" program to land on the moon. Forrest Benson noted as early as October 1961 the excitement that the space program had created within the Tularosa basin. Local and national news media, including Time Magazine, came to the dunes to cover the story, while Defense officials surveyed the Alkali Flats area and its extensions into the monument. Regional director Thomas Allen wrote to the NPS director before Christmas 1961 to express his fears of the "widespread campaign of publicity . . . underway to explain and sell the project to all and sundry." More disturbing to Allen was the fact that "the men under the [WSMR] General's command are engaged in this and omit any reference to the Monument." The regional director echoed the thoughts often expressed by Johnwill Faris when he concluded: "By the time the [spaceport] proposal is final, the National Park Service will be overwhelmed." [47]

No sooner had the NPS begun its investigation of the effect of the space program on White Sands than did the astronaut John Glenn announce upon his return from orbit in February 1962 that the gypsum dunes were "my most fabulous sight." The park service had entered into negotiations with the Defense Department to revise the 20-year special-use permit, in light of the vastly expanded needs of the spaceport. Superintendent Benson realized new constraints on his own staff within their own monument as interest accelerated in military usage. When his rangers were challenged upon entry into the latest impact zone, the WSMR commander ordered that they be escorted by military police. "Although I asked if this project could not be accomplished elsewhere on the [missile] range," said Benson, "[General Shinkle] made no commitment to cancel the mission. " The superintendent then registered the complaint that "this matter of having to call on the General appears to be a continuing harassing procedure." Nonetheless, constant pressure on military encroachment made them aware of the NPS presence. "We cannot physically stop their activity," Benson admitted, "but with repeated contacts they may soon realize that the entire basin is not theirs to do with as they wish." [48]

Whatever the mission of the park service, the political and civic leadership of New Mexico saw in the space program the economic stimulus they needed to lift the state from its fiscal doldrums. Ignoring former President Eisenhower's admonition in January 1961 to avoid dependence upon the "military-industrial complex," Tularosa basin boosters invested in the space port the same energy that they had shown in the 1930s when New Deal spending came with the formation of White Sands National Monument. Senator Clinton Anderson, long a champion of federal spending for science and technology in New Mexico, called upon Defense and Interior officials to explain their "conflicting stories" about the "space port affair." Colonel Lambert, Holloman AFB commander, had told the powerful senator that the Air Force had "no plans" to seek access to monument lands. Forrest Benson reported to his superiors: "There may be no plans, but the attached news clipping indicates somebody is thinking in terms of a spaceport." He then discovered in July 1962 that "more and more items are appearing in the local papers concerning increased military activities in the area adjacent to the monument." These local media had also detected rising hostility toward the park service, said Benson, because they feared that the NPS "may curtail some of this activity involving monument lands, to the detriment of the local economy." [49]

Research into the extension and expansion of the special-use permit ranged far and wide in 1962 and early 1963. In an effort to accommodate the Air Force's position, Washington officials of the park service raised the rhetorical question: Why did the NPS want access to Lake Lucero and the Alkali Flats? The regional office in Santa Fe combed their records, only to find no "determinations for locating the original boundary to include the Flats." An additional discovery was that no evidence existed "to determine geologically which lands within the boundary need to be retained to perpetuate the formation of the gypsum sands." The regional office did learn that a similar study scheduled in 1944 had been cancelled, and they also uncovered Johnwill Faris' comment that year that the NPS could delete 79 sections of land without harming the ecological and aesthetic integrity of the monument. Faris by 1950 had reduced that prediction to 64 sections of land. By 1962, the park service realized that it would have to defend retention of all 149,000 acres of the monument in the face of national security and political economy imperatives. Thus Thomas Allen agreed on March 6 that, "should it be asked for, consideration can be given to issuing the military authorities a permit for use of . . . Alkali Flat." The regional director hoped that this would not include "installation of large structures," and that the park service "could resume use of that land when and if military programs no longer needed it." Allen conceded the weakness of the NPS vis-a-vis the military, however, stating his confusion over the Air Force's denial to Clinton Anderson about use of White Sands. Not only had the local media detailed this, but Allen also had "confirmation . . . as printed and widely distributed in the Rocket Association magazine and newspapers." [50]

Superintendent Benson confronted this lack of NPS support squarely in August 1962 when he paid a courtesy call at WSMR on the new commander, Major General J. F. Thorlin. Since the Interior department had no leverage with the Pentagon, Thorlin's chief of plans, B.H. Ferdig, told Benson bluntly: "It is time we quit dealing under the table and legalize our premeditated encroachments." Ferdig conceded that "[the Army's] attitude toward lands not owned by their agency was in need of considerable improvement," and he feared that the NPS would "give a poor recommendation as to their [WSMR's] compliance with permit restrictions." The chief of plans revealed, however, the inevitability of Kennedy's space and weapons programs. "With the proposed firing from Blanding, Utah, into the White Sands Missile Range," said Benson, "there is no assurance that such missiles will not fall on the monument." Then Ferdig confided in Benson about the massive scale of land use planned for the Apollo moon project. Said the chief of plans: "If you think we are taking over your monument, wait until NASA gets into operation." Benson returned to White Sands outraged at how "the Defense agencies continue to plan and program their projects, then apologize when they are caught." He knew that "apologies wear a little thin after repeated occurrences," and asked his superiors to "help prevent this gradual attrition of our area." [51]

The year 1963 marked the nadir of White Sands' relationship with the space program. For the military, NASA, and New Mexican political and civic leaders, however, that year was one of giddy expectations for economic development. Interior secretary Stewart Udall remembered three decades later that the military, flush with appropriations from Congress and just entering the protracted conflict in Southeast Asia, was "powerful and popular." The Pentagon could usually "get what they wanted," said Udall, and his park service "had to fight back and stop the military." A critical example for Udall came in the spring of 1963, when JFK's Defense and Interior staffs sought closure on the White Sands special-use permit. The draft from the Pentagon, said Thomas Allen, "would give carte blanche use of the eleven western sections of [the monument] . . ., an area of about 150 square miles." This would leave the NPS with 72 square miles, less than one-third the original size of the park. Allen commiserated with Udall's unenviable position "to strike a balance between the importance of certain national defense activities and the preservation of a natural area having scientific value that exists only when unchanged." [52]

Any hope that the park service could forestall the space juggernaut was dashed in the spring of 1963 when the White House announced a planned visit by President Kennedy that June to WSMR. This came on the heels of a story published in March in a Washington journal called Insider's Newsletter. The prestigious trade publication quoted NASA officials as studying the transferral of the manned space flight center from Cape Canaveral, Florida, to the Tularosa basin. Evidence of this was a plan to launch and retrieve a Gemini spacecraft in 1964 from Alkali Flats. In the euphoria generated by this news, Clinton Anderson told the Alamogordo Daily News that Kennedy "wanted to see for himself what New Mexico senators and representatives have insisted is the best area for landing space vehicles in return flights from other planets." As proof of the wisdom of such personal contacts, Anderson remarked that JFK's visit in December 1962 to the Los Alamos and Sandia research laboratories "had a fine effect on nuclear programs and I hope his White Sands visit will likewise stimulate space activities." [53]

Forrest Benson did not share the enthusiasm of his colleagues at WSMR and in the city of Alamogordo. He read in the Insider's Newsletter where Anderson dismissed allegations of political influences, saying: "The decision as to where space projects are located will depend on scientific decisions and what is best for the space program and the U.S. Treasury . . . [and] not on my being on the Senate Space Committee or [U.S. Representative] Tom Morris [D-NM] . . . on the House Space Committee." The superintendent also learned from the local media that "no mention is made of a possible conflicting land use in the middle of this space port proposal." Thomas Allen asked that NPS officials intercede on behalf of White Sands, as he had the "impression that one thing will lead to another very swiftly for new use and that the integrity if not the very existence of the National Monument is being weighed." Allen cited to his superiors in Washington the Anderson quotes, noting how the state's congressional delegation hoped to "explain the program to the President on the ground." The regional director then pleaded: "Perhaps the National Monument's importance could also be brought to [Kennedy's] attention before he arrives." [54]

When the president came to southern New Mexico on June 5, Forrest Benson had little time to speak on behalf of his monument. The primary concern was the fitness of WSMR for the Apollo program, part of the aura surrounding Kennedy as he basked in public opinion approval ratings of 65 percent. His schedule fell behind as the day progressed, and Benson reported that Kennedy's staff cancelled the trip to Alkali Flats. The visit, however, led New Mexico governor Edwin Mechem to appoint a committee of influential people to encourage the selection of WSMR as the primary spaceport site. The group came to the dunes in August 1963, where Benson provided them with "an explanation of the position of the Service as to this non-conforming use." Two months later the monument hosted the "National Parks Advisory Board," which learned first-hand of the military-NPS relationship. All that this official attention could accomplish, however, was a promise by Washington staff that "an integrated geological-ecological study... is the top priority research project in the proposed [NPS] research program for the Southwest Region." [55]

Forrest Benson did not remain at White Sands long enough to see the results of his hectic three-year relationship with the military and space programs. In January 1964, he was detailed to the Washington headquarters to serve as the NPS "representative on the 'Wild Rivers' recreation area studies," an offshoot of the Wilderness Act passed that year. The park service sent as acting superintendent a Southwest Region employee, Lawrence C. Hadley, to manage the monument. Donald Dayton, who would assume Hadley's duties later that October, recalled how volatile the position of White Sands superintendent had become. Stewart Udall, said Dayton, had wanted to "kick out" the military from the dunes. The Defense installations, however, did not change their tune under Hadley or Dayton. One example was the discovery in February 1964 of trash dumps amid the dunes in the northeast quadrant of the park. Chief Ranger Hugh Beattie reported that month being stopped while on patrol by "two investigators from the House Appropriations Committee," while another NPS patrol in March was questioned on monument grounds by "a civilian employee" of WSMR who "asked for security clearance badge and other identification." These interceptions also boded ill for plans to expand back-country hiking in areas targeted for missile impacts, despite the aforementioned rise of interest in camping and wilderness access to the rest of the monument. [56]

By the mid-1960s, tensions between the missile range and White Sands seemed to subside. Impacts still occurred with great regularity (the "Lance" program sent ten missiles over the dunes in the summer of 1965), and a range fire of 150 acres broke out in June 1965 when a missile exploded south of the monument boundary. But that April the Army agreed to provide Donald Dayton with money to pay for a six-month ranger position detailed exclusively for recovery work. The military also began use of helicopters to carry out missile debris, which reduced substantially the damage to the dunes caused by ground vehicles like the 20-ton crane used by WSMR to lift missile fragments onto flatbed trucks. The only difficulty with helicopter recovery was the escalating demand for their use in Vietnam, where U.S. forces needed them for troop transport in that jungle conflict. [57]

The war in Vietnam also ironically shifted the burden on White Sands away from advanced weaponry. Primarily fought by ground troops and pilots using conventional weapons, the war effort required less funding for sophisticated and experimental technology as that under study at WSMR. This did not lessen the intrusions, however, nor the cycle of official apology for recovery crew abuse of the dunes. Especially annoying was the phenomenon of "sonic booms," where loud noises from high speed aircraft shattered the silence over the dunes. But records for White Sands show a decline in staff complaints, perhaps due in part to general acceptance of the circumstances surrounding joint-use. Thus it was interesting for Superintendent Dayton in 1966 to work closely with NASA on "the final test of the Apollo moon probe escape system." Dayton called this "the first large-scale NASA test" for White Sands, and he remarked that "the NASA people were very cooperative in abiding by the Special Use Agreement and the restrictions that we laid down." The project, which involved firing a "Little Joe" booster rocket from WSMR, "received nationwide press coverage." Dayton called NASA "much more cooperative than many of the organizations testing missiles in the monument in the past." He also learned from NASA something that military personnel had refused to admit: that "this area was not now a strong contender [for a spaceport] since the alkali flat runs north and south rather than in the east-west direction needed for any future landing spot for orbiting space vehicles." [58]

|

|

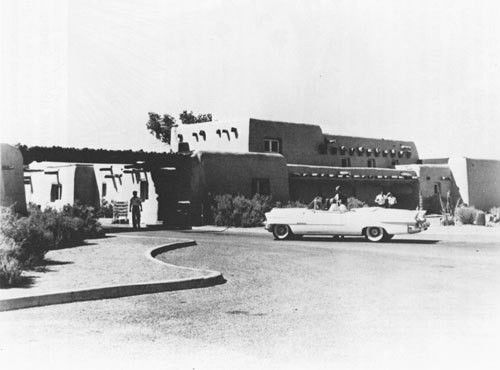

Figure 53. Greeting visitors at old portal entrance at

Visitors Center (1960). Photograph first printed in New Mexico Magazine. (Courtesy Museum of New Mexico. Negative No. 56438) |

The same features of national security that stimulated military and NASA encroachment onto White Sands also hindered a generation's efforts to create a monument at nearby Trinity Site to the first testing of nuclear weaponry. This proved to be less contentious than missile impacts, but no less frustrating for NPS officials eager to meet public demand after 1945 for access to "Ground Zero." Interest in the site, proposed in the 1940s as the "Atomic Bomb National Monument," the "Trinity Atomic National Monument" in the early 1950s, and finally in the 1960s as "Trinity National Historic Site," ebbed and flowed according to organizational dictates. Yet the journey of this historical location mirrored challenges facing White Sands National Monument: eagerness of local boosters to acquire another federally funded tourist attraction; NPS officials divided on the historic merits of the site; ecological constraints typical of the Tularosa basin; and national security policies at odds with the preservation ethic of the park service.

Once the Interior secretary, Harold Ickes, had made known his desire to create the atomic monument in late 1945, local interests approached New Mexico's political leadership for help. Clinton Anderson, then-secretary of Agriculture (1945-1948), wrote to Oscar L. Chapman, assistant secretary of the Interior, in January 1946 to include in the plans for the monument the B-29 bomber that had flown over Hiroshima; Governor John J. Dempsey further promoted the concept, agreeing to release whatever rights-of way that the park service needed across state lands in the basin to provide access to the park. NPS officials were less eager to include the George McDonald ranch house, where J. Robert Oppenheimer and his Manhattan Project colleagues had assembled the final version of the atomic device prior to its July 16, 1945, explosion.

The War Department signaled its support for these efforts in 1946, but wanted to use the B-29 bomber in atomic testing at the Pacific Ocean site of Bikini Atoll. Thus the legislation introduced in the Senate by New Mexico's Carl Hatch (S. 2054) to display the bomber near Alamogordo received no support from the Army. [59]

A series of meetings took place between officials of the NPS, Army, state of New Mexico, and the recently created Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to negotiate the terms of the atomic monument's creation. By May 1946, the El Paso Herald-Post reported: "Park officials say the site in Southern New Mexico may be opened to public inspection within a year." More reason for optimism came in June, when Secretary of War Robert Patterson named Major General Leslie A. Groves as his representative to the interagency monument committee. Groves' stature as military director of the Manhattan Project lent credibility to the park service plan, given the rumors already circulating that the Army would invoke national security as its rationale for refusal to release the land to the NPS . Groves himself could not attend committee meetings, but informed regional officials that his representative, Colonel Lyle E. Seeman, would "extend to you the full cooperation of the Manhattan Project in the establishment of this National Monument." [60]