|

Wilson's Creek National Battlefield Missouri |

|

NPS photo | |

The Battle of Wilson's Creek (called Oak Hills by the Confederates) was fought 10 miles southwest of Springfield, Mo., on August 10, 1861. Named for the stream that crosses the area where the battle took place, it was a bitter struggle between Union and Confederate forces for control of Missouri in the first year of the Civil War.

Border State Politics When the Civil War began in 1861, Missouri's allegiance was of vital concern to the Federal Government. The state's strategic position on the Missouri and Mississippi rivers and its abundant manpower and natural resources made it imperative that it remain loyal to the Union. Most Missourians desired neutrality, but many, including the governor, Claiborne F. Jackson, held strong Southern sympathies and planned to cooperate with the Confederacy in its bid for independence.

When President Lincoln called for troops to put down the rebellion, Missouri was asked to supply four regiments. Governor Jackson refused the request and ordered state military units to muster at Camp Jackson outside St. Louis and prepare to seize the U.S. Arsenal in that city. They had not counted, however, on the resourcefulness of the arsenal's commander, Capt. Nathaniel Lyon.

Learning of the governor's intentions, Lyon had most of the weapons moved secretly to Illinois. On May 10 he marched 7,000 men out to Camp Jackson and forced its surrender. In June, after a futile meeting with Governor Jackson to resolve their differences, Lyon (now a brigadier general) led an army up the Missouri River and occupied Jefferson City, the state capital. After an unsuccessful stand at Boonville a few miles upstream, Governor Jackson retreated to southwest Missouri with elements of the State Guard.

Why Wilson's Creek? After installing a pro-Union state government and picking up reinforcements, Lyon moved toward southwest Missouri. By July 13, 1861, he was encamped at Springfield with about 6,000 soldiers, consisting of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 5th Missouri Infantry, the 1st Iowa Infantry, the 1st and 2nd Kansas Infantry, several companies of regular Army troops, and three batteries of artillery.

Meanwhile, 75 miles southwest of Springfield, Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, commanding the Missouri State Guard, had been busy drilling the 5,000 soldiers in his charge. By the end of July, when troops under Gens. Ben McCulloch and Nicholas Bart Pearce rendezvoused with Price, the total Confederate force exceeded 12,000 men. On July 31, after formulating plans to capture Lyon's army and regain control of the state, Price, McCulloch, and Pearce marched northeast to attack the Federals. Lyon, hoping to surprise the Confederates, marched from Springfield on August 1. The next day the Union troops mauled the Southern vanguard at Dug Springs. Lyon, discovering that he was outnumbered, withdrew to Springfield. The Confederates followed and by August 6 were encamped near Wilsons Creek.

The Battle Despite inferior numbers, Lyon decided to attack the Confederate encampments. Leaving about 1,000 men behind to guard his supplies, the Federal commander led 5,400 soldiers out of Springfield on the night of August 9. Lyon's plan called for 1,200 men under Col. Franz Sigel to swing wide to the south, flanking the Confederate right, while the main body of troops struck from the north. Success hinged on the element of surprise.

Ironically, the Confederate leaders had also planned a surprise attack on the Federals, but rain on the night of the 9th caused McCulloch (who was now in overall command) to cancel the operation. On the morning of the 10th, Lyon's attack caught the Southerners off guard, driving them back. Forging rapidly ahead, the Federals overran several Confederate camps and occupied the crest of a ridge subsequently called "Bloody Hill." Nearby, the Pulaski Arkansas Battery opened fire, checking the advance. This gave Price's infantry time to form a battle-line on the hill's south slope.

The battle raged on Bloody Hill for more than five hours. Fighting was often at close quarters, and the tide turned with each charge and countercharge. Sigel's flanking maneuver, initially successful, collapsed in the fields of the Sharp farm when McCulloch's men counterattacked. Defeated, Sigel and his troops fled.

On Bloody Hill at about 9:30 a.m.. General Lyon, who had been wounded twice already, was killed while leading a countercharge. Maj. Samuel Sturgis assumed command of the Federal forces and by 11 a.m., with ammunition nearly exhausted, ordered a withdrawal to Springfield. The Battle of Wilson's Creek was over. Losses were heavy and about equal on both sides—1,317 for the Federals, 1,222 for the Confederates. The Southerners, though victorious on the field, were not able to pursue the Northerners. Lyon lost the battle and his life, but he achieved his goal: Missouri remained under Union control.

The Civil War in Missouri The Battle of Wilson's Creek marked the beginning of the Civil War in Missouri. For the next 3½ years, the state was the scene of fierce fighting, mostly guerrilla warfare, with small bands of mounted raiders destroying anything military or civilian that could aid the enemy.

The Confederates made only two large-scale attempts to break the Federal hold on Missouri, both of them directed by Sterling Price. Shortly after Wilson's Creek, Price led his Missouri State Guard north and captured the Union garrison at Lexington. He and his troops remained in the state until early 1862, when a Federal army drove them into Arkansas. The subsequent Union victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March kept organized Confederate military forces out of Missouri for more than two years.

In September 1864 Price returned to Missouri with an army of some 12,000 men. By the time his campaign ended, he had marched nearly 1,500 miles, fought 43 battles or skirmishes, and destroyed an estimated $10 million worth of property. Yet the campaign ended in disaster. At Westport on October 23, Price was soundly defeated in the largest battle fought west of the Mississippi and forced to retreat south. By the end of the Civil War, Missouri had witnessed so many battles and skirmishes that it ranks as the third most fought-over state in the nation.

About midmorning on the day of the battle, as he was leading a charge of the 2nd Kansas Infantry against Col. Richard Weightman's Missourians, Gen. Nathaniel Lyon was struck by a bullet that passed through his chest. Slowly dismounting, the mortally wounded Lyon collapsed into the arms of orderly Pvt. Ed Lehmann. A granite marker, placed there in 1928 by the University Club of Springfield, Mo., marks the approximate spot where Lyon was killed, commemorating the death of one of the Union's outstanding officers.

The Men Who Commanded the Armies

Benjamin McCulloch commanded the Confederate forces at Wilson's Creek. Though possessing no formal military training he was a veteran Indian fighter, participated in the Texas War of Independence, and commanded a company of Texas Rangers in the Mexican War. After serving as sheriff of Sacramento during the California gold rush he was appointed U.S. marshal for the eastern district of Texas. McCulloch rose from a colonel of state troops in February 1861 to a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army in May that same year. Seven months after the Confederate victory at Wilson's Creek he was killed while leading a division of troops at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark., March 7, 1862.

Maj. Gen. Sterling Price commanded the Missouri State Guard at Wilson's Creek. He had served in the Mexican War, the U.S. Congress, and as governor of Missouri. He accepted the command of the State Guard when the war began. At age 51 he was the oldest of the six principal commanders at Wilson's Creek and was well-liked by his troops, who affectionately nicknamed him "Old Pap."

Nicholas Bartlett Pearce graduated from West Point in 1850 and served on the frontier for eight years before resigning from the U.S. Army. When Arkansas seceded in early 1861 its Confederate state government commissioned him a brigadier general in charge of volunteers. At the Battle of Wilson's Creek he commanded all Arkansas state troops.

Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, who commanded the Federal forces at Wilson's Creek, was an 1841 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and a veteran of the Seminole and Mexican wars. He had also served at various posts on the frontier before being assigned to the U.S. arsenal in St. Louis in 1861. An ardent Unionist and a strong supporter of Lincoln and the Republican party, Lyon worked closely with Missouri Congressman Francis P. Blair Jr. to prevent the state from seceding from the Union. His death at Wilson's Creek at the age of 43 made him the first Union general to die in battle during the Civil War.

German-born Franz Sigel was director of public schools in St. Louis at the onset of the Civil War. As colonel of the 3rd Missouri Infantry he took part in the capture of Camp Jackson in May 1861 and fought in the Battle of Carthage two months later. The defeat of his brigade at Wilson's Creek helped forge the Southern victory.

Maj. Samuel Sturgis, who assumed command of the Union forces after Lyon's death, was an 1846 graduate of West Point. He, like Lyon, had served in the Mexican War and on the frontier. When the Civil War began Sturgis was in command of the U.S. Army post at Fort Smith, Ark. Cited for meritorious service at Wilson's Creek and in later battles, he rose to major general by war's end.

When Pvt. Eugene Ware wrote the history of the regiment in which he fought at Wilson's Creek—the 1st Iowa Infantry—he remembered the battlefield as "having some scattered oaks and an occasional bush" but otherwise open ground upon which "everything could be distinctly seen. . . ." Time has changed all that. Today, visitors must stretch their imaginations to picture the battlefield as it appeared to Private Ware and other soldiers. The National Park Service, however, has begun to remedy this by launching a long-range program to restore a semblance of the battlefield's historic 1861 landscape. For more information about this restoration, please ask a park ranger.

The Battlefield Tour

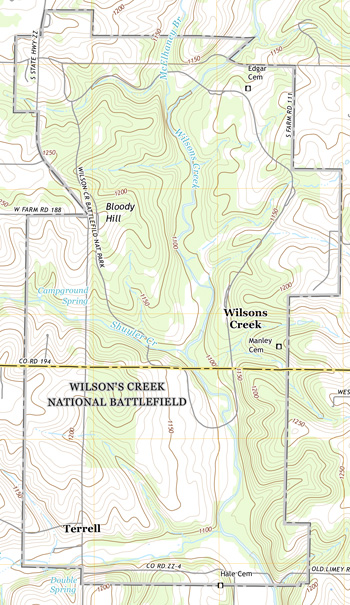

(click for larger maps) |

By Way of Introduction

The battlefield is located three miles east of Republic and 10 miles

southwest of Springfield, Mo. From I-44, take Exit 70 (Mo. MM) south to

U.S. 60. Cross U.S. 60 and drive 0.75-mile to Mo. ZZ. From U.S. 60 and

U.S. 65, take the James River Expressway to the Mo. FF exit, then south

to Mo. M. Follow Mo. M west to Mo. ZZ. A park entrance fee is

charged.

The visitor center features a film, a battle map, and a museum to provide an introduction to the battlefield and its relevance to the Civil War. Guided tours, historic weapons firing demonstrations, and other interpretive services are provided in spring, summer, and fall. Check at the visitor center for current schedules. A picnic area and trails are available.

Regulations

Wilson's Creek National Battlefield is committed to the protection of

our resources, as well as providing visitors with a safe park

experience. For these reasons, firearms, other weapons, and the use of

metal detectors are prohibited; buildings, plants, and natural features

should not be disturbed; pets must be on a leash and are not allowed in

buildings; horses are restricted to authorized trails; and speed limits

and other traffic laws must be obeyed. All accidents should be reported

to park personnel in the visitor center.

Constructed about 1852, the Ray House is the only surviving dwelling in the park associated with the battle. It served as a local post office from January 1856 until September 1866, with John A. Ray as postmaster. The house also served from November 1858 until March 30, 1860, as a flag stop on the Butterfield Overland Stage route. On August 10, 1861, the Battle of Wilson's Creek placed the Civil War squarely on the Ray doorstep. From here throughout the next four years the Rays watched soldiers and the tools of war march past on the old Wire Road before peace finally returned to their lives and the nation.

Stops Along the Tour Route

The auto tour of the Wilson's Creek battlefield is a 4.9-mile, one-way loop road that takes you to all the major historic points on the battlefield. Each stop has wayside exhibits with maps, artwork, and historical information concerning the battle. There are also walking trails at Gibson Mill, the Ray House, the Pulaski Arkansas Battery and Price's Headquarters, Bloody Hill, and the Historic Overlook (tour stop 8). Exhibits are provided at specific locations on the trails. A detailed, 42-minute audio tour of the battlefield can be purchased at the visitor center.

Special Note: The one-way tour road is 18 feet wide. The 12-foot-wide left lane is for vehicular traffic; the six-foot-wide right lane is for walking, jogging, and bicycling. Please drive carefully.

1 Gibson Mill This area marks the northern end of the Confederate camps, with Missouri State Guard Gen. James S. Rains establishing the headquarters of his 2,500-man division near the mill. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon's dawn attack quickly drove Rains's division south down the creek. A trail leads to the Gibson house and mill sites.

2 Ray House and Cornfield The Ray house was used as a Confederate field hospital during and after the battle. Confederate Col. Richard Weightman died in the front room, and the body of Union Gen. Nathaniel Lyon was brought here at the end of the fighting. The small stone building at the foot of the hill is the Ray springhouse, the family's source of water and the only other surviving wartime structure in the park. The only major fighting to take place on this side of Wilsons Creek occurred on the hill northwest of here in the Ray cornfield, from which Union forces were driven back across the stream. The wooded eminence on the western horizon beyond Wilsons Creek is Bloody Hill, where the most intense and savage fighting took place.

3 Pulaski Arkansas Battery and Price's Headquarters From the wooded ridge to the northwest, the cannon of the Pulaski Arkansas Battery opened fire on Bloody Hill, halting the Union advance and giving Confederate infantry time to form into line of battle and attack Lyon's forces. This battery from Little Rock, Ark., fired on Lyon's forces on Bloody Hill throughout the battle. Near here to the west, Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, commander of the Missouri State Guard, established his headquarters in the yard of William Edwards's home in the middle of the 12,000-man camp of the Southern army. It was here that Price and Gen. Benjamin McCulloch first learned of the Union attack.

4 Sigel's Second Position On the ridge across Wilsons Creek to your left, Col. Franz Sigel's Union artillery heard Lyon's attack to the north and opened fire on the 1,800 Southern cavalry camped in this field. The Confederates were routed and fled into the woods to the north and west. Crossing to this side of the creek, Sigel halted about a quarter mile in front of you and formed his 1,200-man force into line of battle to oppose a Confederate cavalry regiment positioned in the north end of this field. After a 20-minute artillery bombardment, the Southerners withdrew and Sigel continued his advance.

5 Sigel's Final Position Sigel halted his advance on this hillside and formed his men into line of battle across the Wire Road. Here he was attacked and defeated by Confederate troops, whom he mistook for a Federal regiment. This critical error proved very costly, as it turned the tide of the battle in favor of the Confederates.

6 Guibor's Battery Not far from here Capt. Henry Guibor placed his battery in position with the Confederate line of battle. From its position, the battery dueled with Union artillery on the crest of Bloody Hill. On three separate occasions Confederate infantry mounted attacks through these fields and woods, but the Union line held and each attack was defeated. When the Southerners made their fourth assault up this hill, they found the Federals had abandoned the crest and were retreating.

7 Bloody Hill Throughout the battle General Lyon's 4,200-man command held this high ground against repeated attacks. At the peak of the fighting, the entire south slope of the hill was covered with battle smoke. When the fighting ended, more than 1,700 Union and Confederate soldiers had been killed or wounded here. Among the fatalities was General Lyon himself. A 0.75-mile walking trail leads past the site of Totten's Battery, the Lyon marker, and a sinkhole where 30 Union soldiers were hastily buried.

8 Historic Overlook The Union army crossed this field both upon their advance to and retreat from Bloody Hill. To guard against a Confederate attack, the 2nd Missouri Infantry Regiment and Du Bois's artillery battery were formed in line of battle in this area. The John Ray house is clearly visible to the southeast.

This concludes your auto tour of Wilson's Creek National Battlefield. Follow the tour road to return to the visitor center parking lot.

Source: NPS Brochure (2005)

|

Establishment

Wilson's Creek National Battlefield — December 16, 1970 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Socioeconomic Atlas for Wilson's Creek National Battlefield and its Region (Jean E. McKendry, Kimberly L. Treadway, Adam J. Novak, Gary E. Machlis and Roger B. Schlegel, 2001)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield: 1996-2010 Status and Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2013/754 (David E. Bowles, June 2013)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield: 2005-2007 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2010/287 (David E. Bowles, February 2010)

Archeological Overview and Assessment for Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Greene and Christian Counties, Missouri Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 66 (Douglas D. Scott, 2000)

Archeological Survey and Testing of the Proposed Tour Road, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 11 (Susan M. Monk, 1985)

Archeological Survey of Tree Removal Zones at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 15 (Jack H. Ray and Susan M. Monk, 1984)

Archeological Testing at the Ray House: Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 10 (Susan M. Monk, 1985)

Archeological Survey and Testing at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield: Tour Road Alternatives A, B and C (Mark J. Lynott, Susan M. Monk, Jeffrey J. Richner and Therese Ryder-Chevance, 1982)

Bird Community Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2013/726 (David G. Peitz, April 2013)

Bird Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2008 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2009/195 (David G. Peitz, April 2009)

Chinquapin Oaks on Bloody Hill, Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2011/155 (Karola E. Mlekush, April 2011)

Community & Conflict: The Impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks (Springfield-Greene County Library District)

Cultural Landscape Report, Volume 1: Wilson's Creek National Park, Republic, Missouri (John Milner Associates, Inc., September 2004)

Cultural Landscape Report, Volume 2: Wilson's Creek National Park, Republic, Missouri (John Milner Associates, Inc., September 2004)

Draft General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield (April 2002)

Effects of multiple intense disturbances at Manley Woods, Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2008/123 (Sherry A. Leis and Kevin James, November 2008)

Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield (April 2003)

Fish Community Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield: 2006, 2007 and 2010 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2011/176 (Hope R. Dodd, David E. Bowles, Samantha K. Mueller and Myranda K. Clark, June 2011)

Foundation Document, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri (January 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri (January 2017)

Geologic Map of Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri (August 2024)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report: Wilson's Creek National Battlefield NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2025/255 (Michael Barthelmes, March 2025)

General Management Plan, Environmental Impact Statement: Wilson's Creek National Battlefield Final (December 2002)

Hard Times/Hard War: Wilson's Creek National Battlefield Education Packet, Grades 9-12 (Kenneth Elkins, 2nd edition, 1996)

Historical Base and Ground Cover Map, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Greene and Christian Counties, Missouri (Edwin C. Bearss, 1979)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield: Year 1 (2006) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/013 (Craig C. Young, Jennifer L. Haack and Holly J. Etheridge, March 2007)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Kansans Go to War: The Wilson's Creek Campaign Reported By the Leavenworth Daily Times: Part I (Richard W. Hatcher and William Garrett Piston, eds., extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 16 No. 3, Autumn 1993)

Kansans Go to War: The Wilson's Creek Campaign Reported By the Leavenworth Daily Times: Part II (Richard W. Hatcher and William Garrett Piston, eds., extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 16 No. 4, Winter 1993-1994)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield (June 2009)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Wilson's Creek Battlefield (Thomas P. Busch, March 26, 1976)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR-2011/427 (Gust M. Annis, Michael D. DeBacker, David D. Diamon, Lee F. Elliott, Aaron J. Garringer, Phillip A. Hanberry, Kevin M. James, Ronnie D. Lee, Michael E. Morey, Dyanna L. Pursell and Craig C. Young, July 2011)

No Easy Choices: Taking Sides in Civil War Missouri: Wilson's Creek National Battlefield Educational Packet, Grades 7-8 (Kenneth Elkins and Jeff Patrick, 1997)

The 1983 Archeological Excavations at the Ray House, Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 15 (W. E. Sudderth, 1992)

"The Fire Upon Us Was Terrific:" Battlefield Archeology of Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 109 (Douglas D. Scott, Harold Roeker and Carl G. Carlson-Drexler, 2008)

The Fishes of Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri, 2003 U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5127 (James C. Petersen and B.G. Justus, 2005

The Wilson's Creek Staff Ride and Battlefield Tour (George E. Knapp, March 1993)

Tree survey of Historical Viewshed Area at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2020 Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN (Naomi S. Reibold, David G. Peitz and Mary F. Short, December 2020)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield: Project Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/WICR/NRR—2013/650 (David D. Diamond, Lee F. Elliott, Michael D. DeBacker, Kevin M. James, Dyanna L. Pursell and Alicia Struckhoff, April 2013)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2008-2011 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2012/234 (Karola E. Mlekush and Kevin M. James, January 2012)

Vegetation Community Monitoring Trends in Restored Tallgrass Prairie at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2008-2020 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2022/2368 (Sherry A. Leis, March 2022)

White-tailed Deer Monitoring at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2005-2006 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2006/016 (David G. Peitz, May 2006)

White-tailed Deer Monitoring at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2007 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/027 (J. Tyler Cribbs and David G. Peitz, March 2007)

White-tailed Deer Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2008 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2008/102 (J. Tyler Cribbs and David G. Peitz, April 2008)

White-tailed Deer Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2005-20218 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR-2018/1703 (David G. Petiz, Jennifer L. Haack-Gaynor, Lloyd W. Morrison and Mike D. DeBacker, April 2018)

White-tailed Deer Monitoring at Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Missouri: 2005-2022 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR-2022/2481 (David G. Petiz, November 2022)

Wilson's Creek National Battlefield (Allan B.. Cooksey and Peter A. Oppermann, extract from Parkways: Past, Present, and Future, 1987)

wicr/index.htm

Last Updated: 22-Mar-2025