|

YELLOWSTONE

The History of the Construction of the Road System in Yellowstone National Park, 1872-1966 Historic Resource Study, Volume I |

|

|

Part One: The History of the Construction of the Road System in Yellowstone National Park, 1827-1966 and the History of the Grand Loop and the Entrance Roads |

CHAPTER XII:

HISTORY OF GRAND LOOP ROAD*

*In order for this document to be useful as a management tool, the history of the Grand Loop Road's construction has been divided into the following seven sections: Mammoth Hot Springs to Madison Junction, Madison Junction to Old Faithful, Old Faithful to West Thumb, West Thumb to Lake Junction, Lake Junction to Tower Junction, Tower Junction to Mammoth Hot Springs, Norris Junction to Canyon Junction.

MAMMOTH HOT SPRINGS TO MADISON JUNCTION

During Superintendent Philetus Norris' first year, 1877, in Yellowstone, he proposed a route or bridle-path from Mammoth Hot Springs to the Firehole River region via the Gardner Falls and the Gibbon River which would connect the only two entrances to the Park, the west and north. This proposal was part of a larger scheme which included the construction of a wagon road from Mammoth Hot Springs to Henry's Lake via the Tower Falls, Mount Washburn, Yellowstone Falls, Yellowstone Lake, Firehole Basin, and exiting the Park on the older western route into the geyser basin region. Norris felt that the wagon road would connect almost all of the major points of interest and also connect the two entrances into the Park. In addition to the Mammoth Hot Springs to Firehole bridle-path, another bridle-path was proposed, from the Stillwater River to the Upper Geyser Basin via the Clark's Fork mines, Soda Butte, through the petrified forests to Amethyst Mountain, Pelican Creek, the outlet of Yellowstone Lake, Shoshone Lake, and on to Old Faithful in the geyser basin. Norris also planned to build facilities at Mammoth Hot Springs.

Upon arriving in the Park the following year with the first congressional appropriation of $10,000, Norris' priorities for building facilities and beginning the construction of the wagon road were changed due to the previous year's conflict with the Nez Perce Indians and a continual threat from the Bannock Indians. Instead, Norris began construction of the first permanent road in the Park, Mammoth Hot Springs to the Lower Geyser Basin. Completion of the road would facilitate the movement of military from Fort Ellis, Montana, to Henry's Lake in Idaho or Virginia City, Montana and of course, would be used by the ever-increasing number of visitors to the Park. [1]

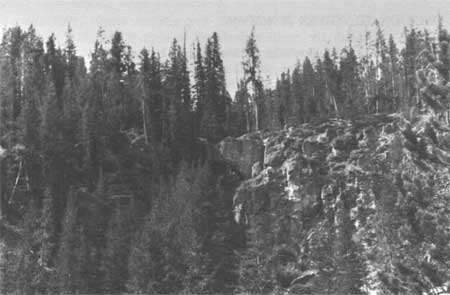

Prior to his explorations for appropriate routes, Norris viewed possible routes from the top of Sepulcher Mountain. He could spot the route that he had taken in 1875 and he visualized a route to the south through the park via Gibbon Canyon, Firehole Basin, the Continental Divide and on to the Tetons. Norris knew construction through the canyons could prove difficult and dangerous, but it appeared to be the most straightforward and practical wagon route. [2] Furthermore, the unusual conditions, the presence of huge masses of obsidian, in the Obsidian Cliff area posed problems for road construction.

In the survey of the road section immediately south of Mammoth Hot Springs, Norris located three possible routes from Mammoth Hot Springs to the plateau near Swan Lake. One route, the longest and most precipitous, followed the Gardner Canyon over the pass via the Osprey Falls and Rustic Falls to the plateau (route later became the Bunsen Peak Road); another route, which had a more gradual grade but also had a sheer wall section to be transversed, was the opening created by Glen Creek on to Swan Lake; the third and chosen course was the most direct route, but with steep grades, through Snow Pass above the hot spring terraces. A visitor described this first section through Snow Pass as "So steep is the climb that if the tail-board of a wagon falls out . . . the whole load is promptly dumped out in the road. A good road, though, a longer one, might have been built over the same ground." [3]

From the flat area near Swan Lake to the Obsidian Cliff area, no great construction difficulties were encountered, however penetrating the "glass mountain," Obsidian Cliff took ingenuity. Norris described his technique:

Obsidian there rises like basalt in vertical columns many hundreds of feet high, and countless huge masses had fallen from this utterly impassable mountain into the hissing hot spring margin of an equally impassable lake, without either Indian or game trail over the glistening fragments of nature's glass, sure to severely lacerate. As this glass barricade sloped from some 200 or 300 feet high against the cliff at an angle of some 45 degree to the lake, we . . . with the slivered fragments of timber thrown from the height . . . with huge fires, heated and expanded, and then, . . . well screened by blankets held by others, by dashing cold water, suddenly cooled and fractured the large masses. Then with huge level steel bars, sledge, pick and shovels and severe laceration of at least the hands and faces of every member of the party, we rolled, slid, crushed and shoveled one-fourth of a mile of good wagon-road midway along the slope; it being, so far as I am aware, the only road of native glass upon the continent. [4]

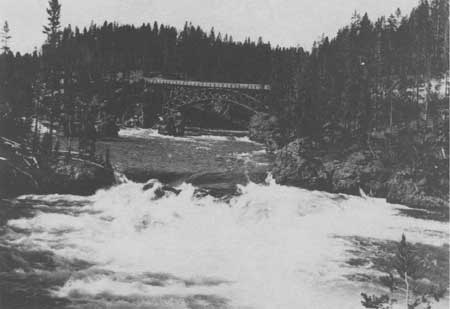

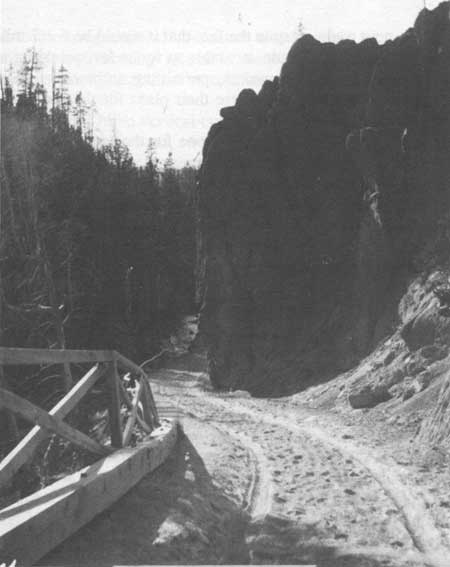

Leaving the "glass mountain," the 1878 road followed in an southeasterly direction to Lake of the Woods, Solfatara Creek into the Norris Geyser Basin. Norris' road proceeded through Elk Park, Gibbon Meadows into the Gibbon Canyon. At an approximate point where the Gibbon River flows in a westerly direction, the road left the canyon in a gap between cliffs and traversed pine covered slopes connecting with the Madison Junction to Old Faithful Road south of the present day Madison Junction.

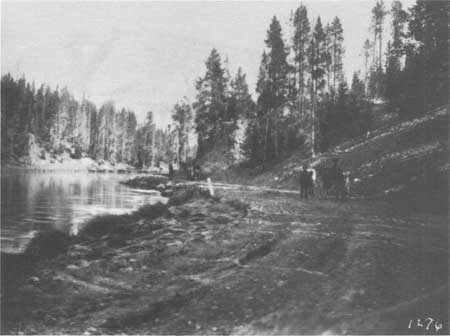

During 1879, Norris supervised improvements to the grades at Obsidian Cliff, in the Norris area and into the Gibbon Canyon. He found spanning the Gibbon, Firehole and Madison rivers, or their creeks and streams could prove to be very interesting. He wrote "Few of the anomalous features of the LAND OF WONDERS are of greater scientific interest or of more practical value than the placid, uniform water-flow in its hot spring and geyser-fed rivulets and streams." Because these water courses are generally "broad, shallow, grassy and flowers carpeted to the water's brim, . . . with long stretches of flowing grass and occasional hot spring pools in the channels, . . . with overhanging turfy banks," Norris decreased the need for some bridges by cutting a slope through the turf forming a very good and permanent ford. Instead of a bridge he placed "long, limber poles and foot-logs, only a few inches above the low stage of water." [5]

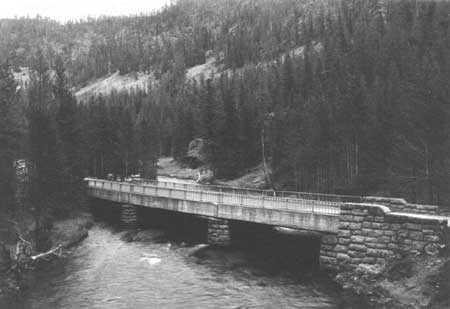

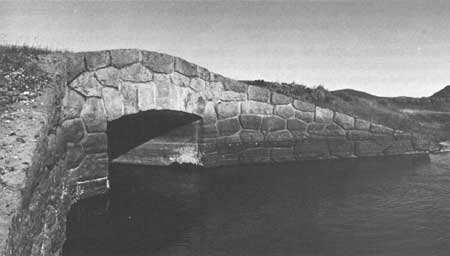

The following season, bridges were built to span the Gardner and Gibbon rivers, including costly, long causeways, turnpikes, and grades along the Norris fork of the Gibbon River. An extension of the road to the Forks of the Gardner River was finished and a road "through the eastern branch nearly half-way through its terrible canon, necessitated a grade of over 1,000 feet within two miles." [6] In 1882, the new superintendent, Patrick Conger who accomplished little in road construction, was responsible for the construction of a substantial bridge over the Gardner River. The construction was supervised by Capt. E. S. Topping. The bridge, which was 12 miles south of Mammoth Hot Springs, was built in two weeks. The 96 feet long structure had abutments built well out into the river on both sides. The center pier and the abutments were constructed of log in a V-shaped configuration, pinned at the corners and filled with rock above the high water mark. The bridge was covered with hewn logs, 5 inches thick. [7] Topping and his crew built and repaired culverts and crossways, removed rocks and boulders, and still Conger wrote "Our road is still in a mountainous and rugged country, requiring much labor and expense before it can be said to be a good road." In his appeal for more appropriations for road work, he described the situation:

. . . when you consider the extent of the territory and the great natural obstructions that have to be encountered, it seems to me it must be evident, . . . the amount heretofore placed at the disposal of the Secretary of Interior for the protection and improvement of Yellowstone National Park is entirely inadequate . . . . But to proceed with our road we have to pass over some very high hills to reach the valley of the main Gibbon, where we encounter a wide low bottom called the Geyser Meadow, a place where it will require a large amount of labor to make a good road. After passing the meadow our road enters the Gibbon Canyon and follows the river down several miles, close on the edge of the stream, crossing the same three times in as many miles over difficult and dangerous crossings in time of high water. After passing through this canyon our road gains the highlands, by a steep grade along the side of the mountain on the south side of the river. We soon come to the great falls of the Gibbon where the river plunges over a perpendicular precipice of 75 feet, which in the stillness of the evergreen forest that covers this country renders the scene as enchantingly beautiful as 'fairyland'. [8]

Army engineer Lt. Dan Kingman, who assumed the responsibility for road construction in the Park in 1883, found this section of road to be the most heavily traveled in the park and in the worst condition. His largest work crews reported there until heavy snows of 18 to 30 inches fell during the middle of October of 1883. With the exception of a 3 miles stretch in the Gibbon Canyon, this 40 miles section was widened and straightened, boulders and stumps removed and slopes reduced. Frequently spaced turnouts and a new ford were built. The existing bridges were repaired and the corduroy sections were covered with sod and earth. The work on this section cost approximately $6,300 or $170 per mile. [9]

In 1885 major projects and changes were made to Mammoth Hot Springs to Firehole Basin area. Substantial bridges were completed, one over the Gardner River at the ford, one over the Gibbon River at the lower ford, and one over the Gibbon River at the third crossing.

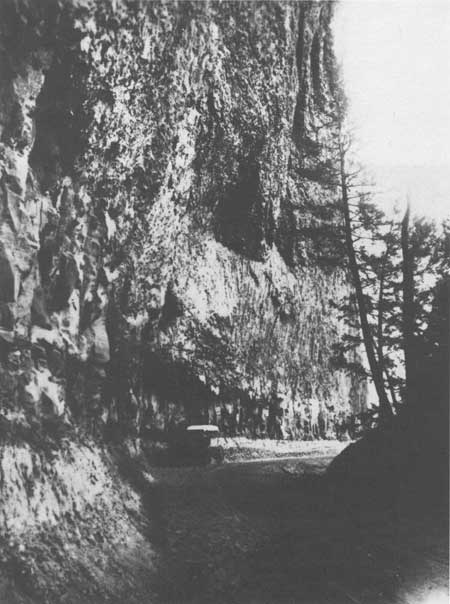

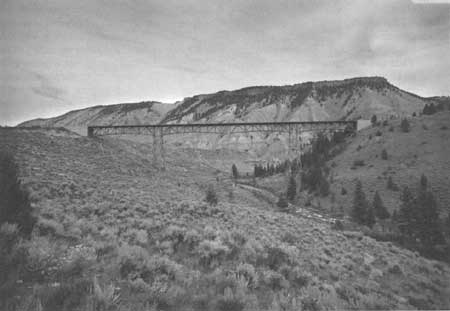

Work was completed on the new route immediately south of Mammoth Hot Springs. The 4-1/2 miles Mammoth Hot Springs to Gardner via Golden Gate and the West Fork of the Gardner River, which was started in 1883, was completed in a seven month period. Twelve hundred and seventy-five pounds of explosives were used and over thirteen hundred shots in drilled holes were fired. As a result, fourteen thousand cubic yards of solid rock was excavated in addition to a large amount of broken and crushed rock. This dangerous section of road was completed without any loss of life or injury. The completion of this section reduced the route by 1-1/3 miles and the time to many areas in the park from 2 hours to 1/2 day depending on the type of wagon and load. The reduced ascent of 250 feet to Swan Lake plateau enabled loaded wagons traveling in opposite directions to now pass with relative ease. The near vertical stone walls of the canyon prevented an excavated roadway, thus a 228 feet wooden trestle carried the roadway. Lieutenant Kingman noted in his report for 1885 that the "natural stone monument at the end of the trestle" marked what "visitors have called the Golden Gate." [10]

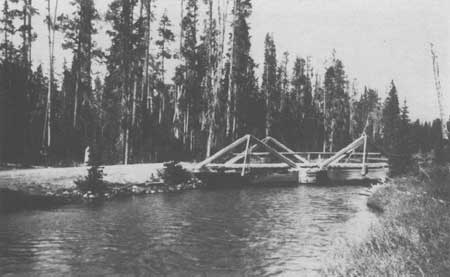

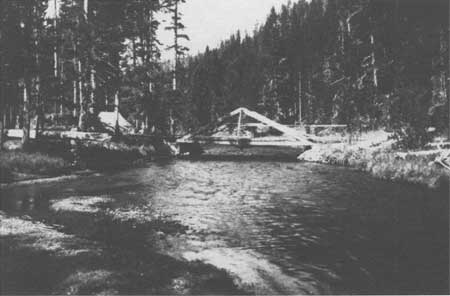

Kingman established a road camp near the Norris Geyser Basin in order to begin work on the new road between Norris Geyser Basin and Beaver Lake where it would connect with the old road at the head of the lake. The poorly located old road ran in an easterly direction south of Beaver Lake, before entering the woods near Lake of the Woods, then the road followed Solfatara Creek and crossing the Continental Divide near the confluence of the rivers near Norris Junction. Due to excessive snow depths and heavy timber covering, the snow covered the road well into May. The poor subsurface drainage caused by the heavy clay soils and the "saucer-like shape" of the pass produced "horrible conditions" for travelers. Kingman noted that it was not uncommon "to see a team lying in the mud, tangled in their harness and floundering about in almost in inextricable [sic] confusion while the drivers looked on in despair." Consequently, Kingman had sought a new route which would provide more exposure to the sun, better drainage and soil conditions. The 7 miles of new road, completed by the middle of October, cost $6,269.80. Before the close of the 1885 season, the crews replaced "a long and rather unsafe structure built of poles" with a "single span King-post truss of 30 feet" combined with a causeway, over the Gibbon River near the Norris Geyser Basin. [11]

In 1887, the wooden trestle through Golden Gate was strengthened by placing new timber supports and road-bearer cross beams. A log and pole temporary bridge had to be placed over Obsidian Creek at the ford due to the unusually high runoff. Lieutenant Kingman's replacement, Capt. Clinton Sears, proposed building a new 7 miles road from Swan Lake Flats to Beaver Lake, a new road between Norris Basin and Gibbon Canyon which would complete the 6 miles gap, and build a new road from Gibbon Canyon to the Firehole Basin. With a small appropriation for 1888, he was able to build a road from Norris Hotel across the Gibbon Meadow connecting with the road into Gibbon Canyon and a 7 miles stretch from Obsidian Cliff northwards. [12]

In 1889, a King and Queen post-truss through span of 40 feet was built over the Gardner River at the south end of Swan Lake Flats. It had a trestle span of 20 feet, a roadway width of 14 feet and a height above low water of 6-1/2 feet. A 86 feet long trestle bridge with a 13 feet and 8 inch width roadway between guardrails, a 5-1/2 feet above the low water, was built over the Gibbon River in the canyon. The engineers felt that a trestle bridge could be safely built because the river, which has many hot springs in its bed, would not receive ice build-up. Thus at the end of 1889, the following bridges were in service on the Mammoth Hot Springs to Madison Junction:

1. three spans of 33 feet over Gardner River—no truss

2. three spans of 32 feet over Gardner River—King post

3. trestle of 224 feet—Golden Gate

4. one span of 14 feet over West Gardner—no truss

5. two spans of 40 feet and 20 feet over Gardner River King and Queen post

6. one span of 32 feet over Obsidian Creek—King post

7. one span of 16 feet over Obsidian Creek—no truss

8. one span of 32 feet over Obsidian Creek—King post

9. One span of 34 feet over Gibbon River—King post

10. one span of 20 feet over slough at Norris—no truss

11. two spans of 40 feet over Gibbon River—Queen post

12. trestle of 75 feet over Gibbon River—Queen post

13. one span of 24 feet over Gibbon River—no truss

14. one span of 24 feet over Gibbon River—no truss

15. one span of 20 feet over Gibbon River—no truss [13]

During 1890, one of the two major projects in the Park was the construction of retaining walls in the Gibbon Canyon area. [14] In 1895, the Army completed another bridge over the Gibbon River at an old ford, near the mouth of the canyon. [15] The next major road projects for this section would be a part of Capt. Hiram Chittenden's 1900 multi-year plan for completion of the Grand Loop Road.

Among Chittenden's proposals for the multi-year project, he recommended a new widened road through Golden Gate Canyon including a new bridge to replace the wooden trestle around the cliff, raising 3 miles of road 2 or 3 feet in Gibbon Canyon and cutting out 1 mile of dangerous grades, and constructing 4 miles of new road down the Gibbon to connect with the western entrance road. [16]

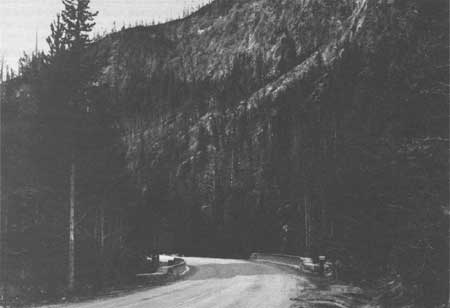

About one mile of the original wagon road along the Gibbon River Canyon remained in 1900. The road had two very steep grades, one of which had a sharp curve at the bottom right at the river's bank. Chittenden found this particular stretch to be most dangerous as the failure of brakes or any other emergency might bring a team and wagon into the river. He called the road through Gibbon Canyon "One of the most pleasing in the park. It runs immediately along the bank of the river and is of easy grade. Unfortunately it is not built high enough above the river to make it safe. The river at every heavy flood goes clear over the road and has washed it out twice in the past six years." By 1903 the two bad grades had been cut out, one mile of new road had been constructed and a new steel bridge with concrete abutments had been built. During the winter of 1902, rock was hauled on sleds for about a mile to be used in the construction of the new heavy retaining wall on the newly reconstructed section of road about a half mile below Gibbon Falls. [17]

In 1904, a worn-out bridge in the Gibbon Canyon was replaced with a small 45 degree skew span and the following year the bridge over the Gibbon near Norris Junction was reconstructed and a steel truss was built over the Gardner River at the 7 mile post (Seven Mile Bridge). [18] Chittenden completed the construction work on the Golden Gate during 1902. [19]

Before Captain Chittenden left Yellowstone to begin supervision of the roads in Mount Rainier, he made the following recommendations for improvements to the Mammoth Hot Springs to Madison Junction road:

. . . great care should be taken in widening the road through the 'Hoodoos' to prevent the destruction of unusual rock formations. It will be better to let the right of way have an irregular alignment—being narrower in some places than in others—than to sacrifice this peculiar formation in order to get a uniform width throughout. . . . it would be better to require all teams to come to a walk there than to remedy the defect by blasting out those picturesque rocks.

Forested areas at Apollinaris Springs, a point 8-1/2 miles from headquarters, Crystal Springs, and at mileposts 13, 14, and 17 miles out should be cut back on the east side about 30 feet to expose the snow to the sun. However, if these forests contained fine specimens of trees, the stands should be preserved. The Apollinaris Spring, Kepler Cascade, Mud Geyser and other coach unloading platforms should be rebuilt and extended to a length of 100 feet.

The first hill just beyond the Growler can probably be brought to the adopted grade of 8% by a small amount of cutting and filling and no relocation of the old road is deemed necessary. The second hill just beyond the first milepost can probably be dealt with better by going around it to the south. A personal reconnaissance of the ground indicates the entire practicality of such a line. If built, it should leave the present road at the foot of the first hill near the Minute Man Geyser and rejoin near the foot of the second hill at the beginning of the tangent across Elk Park.

The maintenance of the retaining wall along the Gibbon River between Elk Park and Gibbon Meadow can probably be avoided advantageously by putting the road back farther into the rock. If the wall is retained it will have to be relaid in mortar. [20]

1st Lt. Ernest Peek, who replaced Hiram Chittenden, agreed with Chittenden's earlier suggestion of building all stone drywalls in the park and in 1907 began repairs on the drywalls near Gibbon Falls. In order to efficiently coordinate the work on this section, he established a number of road camps including one near Obsidian Cliff and one near Beryl Springs. The camps had floored and frame tents. [21] In 1908, Peek requested sufficient funds to purchase three bridges, including two for the Gibbon River, but his request was not honored. Thus very little major work occurred, but road surfacing was carried out from Silver Gate to the 5 milepost across from Swan Lake Flats. Near Crystal Spring, "considerable work was done on the roadside in order to deepen the ditches and give the road a good high crown." Surfacing was also done on the Norris to Fountain road from 2-1/2 to 2-3/4 miles. The 25 foot bridge at Obsidian Cliff and the 15 foot bridge at Apollinaris were each replaced by fills with 4 feet culverts. At Obsidian Cliff, the road was raised over 2 feet to improve the grade and it was also straightened. A fill of a foot was also made at Apollinaris. [22]

In 1909, Army Captain Willing conducted an inspection of the bridges in the Park which stated condition and made recommendations for improvements. On this section of the road, Willing found:

Bridge No. 2 across the Gibbon River, 5-5/8 miles south of Norris Station—The present structure consists of one wooden span with two wooden approaches, and was built in 1895. The timber in the bridge is sawed pine lumber, which at present is in a decaying condition, some of the floor beams being broken and held in place by props. The structure is in an unsafe condition, and it is recommended that it be replaced by two 50' low truss, pin connected steel spans, resting on two concrete abutments and one concrete center pier.

Bridge No. 3, Gibbon Canon Bridge, across Gibbon River, 7 miles south of Norris—The present structure is a trestle bridge 80' long, built 1891, of sawed pine timber which is in a decaying condition. It is recommended that this bridge be replaced by an 80' low truss, pin connected steel span, resting on concrete abutments. As the bridge crosses the stream, at an angle of about 45 degrees, it will be necessary to make this bridge askew.

Bridge No. 4, Gibbon Canon Bridge, across Gibbon River, 9 miles south of Norris Station. The present bridge consists of two piers in the stream, two abutments of logs, and log stringers spanning the space between these piers. It was built in 1892, is 65' long is in shaky and decaying condition. It is recommended that it be replaced by a 65' low truss, pin connected steel span, resting concrete abutments. It will be necessary that this bridge also be built askew as the road crosses the river at an angle of about 45 degrees.

Bridge No. 5, across the Gibbon River at Wylie's Lunch Station. The present structure consists of one pier in the middle of the stream, and two log abutments with log stringers spanning the space between. The bridge was built about eight years ago and is in a fair condition, but two light in construction for the travel it has to carry. It is recommended that it be replaced by a 40' steel plate girder span, resting on concrete abutments.

Bridge No. 7, at the mouth of the Gibbon River, near the junction with Firehole River. The present bridge consists of one wooden span with approach at one end, resting on wooden piers and abutments, total length 66'. This bridge was built in June and July, 1896, and is also in the advanced state of decay and is unsafe. It is recommended that this bridge be replaced by a 65' low truss, pin connected steel span, resting on concrete abutments. [23]

During 1909, the road between mileposts 8 and 15 was ditched and crowned and the road was raised about 1-1/2 feet at the culvert fill across Willow Creek. The ruts caused by heavy traffic and water were filled with surfacing material. [24] In 1911, the road from Gardiner to Norris Junction was regraded and 21 miles of the road was graveled. Also that year, the engineers recognized the need to replace section of the dry, rubble wall along the Gibbon River. [25] During the winter of 1912, Captain Knight recommended that additional dry rubble guard walls be built on the outside edges of curves through the Golden Gate. He suggested the road along the Gibbon River between points 8 and 9 be raised two feet for 1-1/2 miles to keep it from overflowing in the spring and that sections of the dry rubble retaining walls be rebuilt. [26] He also felt that the old, crumbling retaining wall between Norris and Fountain should be replaced and that the narrow road should be widened. [27]

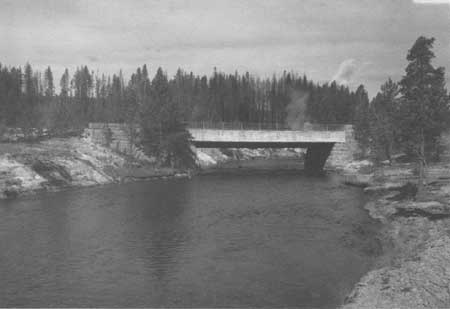

In 1914, gravel was placed over the middle 8 to 10 feet of the Golden Gate to Swan Lake Flats road to bring up the crown and fill in the wagon ruts. The gravel, which was taken from a pit just east of the 4 milepost was loaded through a trap by drag scrapers. It took approximately 1/4 yard of gravel per linear foot of road. [28] Some of the old bridges on the Mammoth Hot Springs to Madison Junction were replaced during the year. A two 40 feet span reinforced concrete bridge was built over the Gibbon River, 7 miles from Norris, and one 65 feet single span girder and slab constructed bridge was built over the Gibbon near the confluence with the Firehole River. A 40 feet steel arch bridge was built over the Gibbon River near the Wylie Camp, 17 miles from the West Entrance. More reconstruction of stone retaining walls was done in the Gibbon Canyon and the road crews built a barn in the Gibbon Meadows camp, a cabin at the Beaver Lake camp, and two "public-comfort houses" were built in the Norris Geyser Basin. [29]

No major road projects occurred on this section of the Grand Loop Road for a few years. Shortly after the National Park Service was created, Secretary of the Interior, Franklin Lane visited the Park. During his inspection of the road system, he recognized a safety and visual problem in the Gibbon Canyon, the growth of small trees along the road. He found that the trees obstructed the view of the river and in turn made for dangerous driving. He also felt the removal of a few trees at the Gibbon Falls would "afford a better view of the falls." Other comments of condition on this section were:

On top of hill on main road two miles from Mammoth, a number of very bad and hard rolls and bumps. Two serious holes, more than half way across Swan Lake Flats. Bridges at Upper Gardner River, Willow Creek and Gibbon River at Norris, below and above road levels. Road at Roaring Mountain in poor shape. Road Norris to Fountain down the Gibbon Canyon very rough, full of large chuck holes and broken culverts. Also contains one or two improvised log bridges where culverts have been washed out. Wylie Gibbon Camp over Mesa Road to Firehole River, about four very bad chuck holes that could be filled with little expense. [30]

During 1921, a new steel and concrete bridge was placed over the Gibbon River near Norris and wooden mess halls were built at Madison Junction and at Gibbon Meadows. [31] For the next few years, small allotments financed minor road projects, mostly accomplished on short sections at the end of the season. In September 1927, a crew composed of men and teams from disbanded work groups, began a grading project along the Gibbon River. The 1928 appropriation provided sufficient funds for work for a complete season. Foreman John Benson established a temporary work camp at milepost 17 on May 17, 1928 in order to begin the heavy steam shovel work in rock cuts and to arrange detours for traffic. Later the camp was moved to Norris Junction to continue the project which was finally finished in May 1929.

In June, 1930, Foreman O.A. Weisgerber established a camp at the old Beaver Lake road camp in order to begin work on the Bijah Springs-Obsidian Cliff section. A dangerous curve was reconstructed near milepost 15 and between the Gardner River crossing and the Glen Creek crossing, the crews were stalled by underground springs which required the installation of subdrainage. Material from a rhyolite slide north of Obsidian Cliff was used for a rock sub base. An Osgood gas shovel, which had been moved up the Gibbon River-Norris Junction section was used on this section. The next section mostly required light cuts in the existing roadway and side cuts to straighten and widen the road. On this section, the banks were sloped up to an 8 or 10 feet cut on a 1-1/2 and a 2 to 1 slope. It was felt that the slopes, which would present a pleasing appearance, would also suffer less erosion from heavy runoff and the vegetation would take root easily. Upon completion of the excavation of this segment, the shovel removed rhyolite material from a pit behind the Norris Ranger Station for use as a light coating material for surfacing. The camp was dismantled in November. [32]

In October, 1929, when the weather became too bad to work in the interior of the Park, the crews resumed work on 600 feet of road in the Mammoth Lodge area. Most of the project was in fill, but the additional rough fill material needed was obtained from the demolished concrete grainery near the Tower Falls and Mammoth Hot Springs junction and from abandoned concrete flumes near the Mammoth Lodge. The removal of these structures were part of the Landscape Division's plan for the Mammoth area. The rough fill was covered by material obtained from the road slopes above the Mammoth reservoir and the finer material for surfacing came from the pit on Capitol Hill. In addition to the road construction, the old wooden sidewalk and the continuing gravel walk to the Mammoth Lodge was replaced with a stone curb sidewalk. The new sidewalk was described as:

a stone curb walk, 2,412 feet in length, and with an emulsified asphalt surface. Curbing of locally quarried sandstone, is twelve inches wide and with a clear face of eight inches on the street side. Width of walk between curbs is five feet, an overall width of seven feet. The space between curbs was filled to within three inches of the top with any available material. Above this was spread two courses of grade size gravel, each coat being sprayed with a penetrating coat of Bitumen and rolled to a true cross section. A final coat of fine native sand was then broomed into the surface, giving a natural gray finish to the walk. [33]

After the Bureau of Public Roads assumed the road construction and improvement responsibilities for the Park in 1926, the Mammoth Hot Springs to Madison Junction was considered as a major project, however, adequate funding for location surveys was not received until 1929 and 1930 and as earlier stated, the lower segment of the section was constructed by National Park Service day labor work. The location survey for the Mammoth Hot Springs to Obsidian Cliff segment was made during the fall of 1930. At that time additional funds were requested for more investigation of the Golden Gate and for designs for a new viaduct.

A better route south from Mammoth Hot Springs was investigated, however, an improvement to the existing route through Golden Gate was deemed more advisable than the old route through Snow Pass and/or Bunsen Peak, or a preliminary proposal by the Park's engineering department of following a higher location through Golden Gate Canyon toward Mammoth Hot Springs through the Hoodoos. The National Park Service's landscape division did not approve of cutting.

The Bureau of Public Roads' proposed route followed the older Army road from Mammoth Hot Springs south except at the Gardner River crossing and the Obsidian Creek crossing, where it moves approximately 1/4 mile eastward for a distance of about 3/4 mile.

The 18 feet standard roadway design by the Bureau of Public Roads was used on this road segment. The design provided an 18 feet surfaced roadway with three feet shoulders on each side, both on fills and cuts. Three feet standard ditches, one foot deep with 2 to 1 slopes into the ditch, from the shoulder, were provided for sections in cuts. The cut slopes were designed for slopes 1 to 1 or flatter in common material as specified by the Landscape Division of the National Park Service. For the use of materials other than common, the cut slopes were designed at slopes thought to be stable for the particular material, except that all cuts four feet were designed with one to one slopes. The fill slopes were all designed at 1-1/2 to 1.

The Bureau called for the use of corrugated, galvanized metal pipe culverts with cement rubble headwalls for the minor drainages and for reinforced concrete box culverts with cement rubble headwalls for creek crossings. They also recommended the construction of a reinforced concrete structure, 75 or 80 feet long of 2 or 3 spans at the crossing of the Gardner River at station 233 +50.

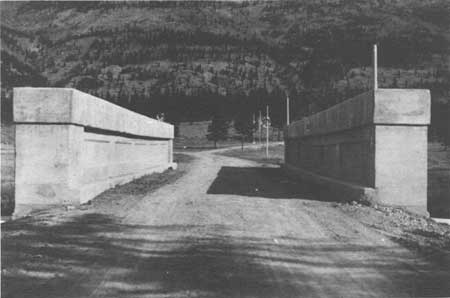

In assessing the Golden Gate viaduct situation, the Bureau found the present viaduct below the grade of the located line and too narrow thus, a new a new viaduct was necessary. In order not to incur further scarring, a wider and slightly higher structure was needed. They recommended cement rubble retaining walls on either end of the viaduct and the respective length of the wall. The new reconstruction would also require a tunnel approximately 100 feet in length.

Finding snow conditions worse in the Swan Lake Flats area, snow fences were suggested to control the conditions on the flats. The Bureau did not project possible snow conditions at either entry to the tunnel, but they did try to consider snow problems on the route in case of possible winter use of the road.

A sand and gravel pit on Swan Lake Flats was approved for concrete aggregate material, but its conspicuous location limited the amount that could be extracted from it. [34]

Following the completion of the Location Survey, the Denver office of the Bureau of Public Roads designed the road and also the plans and specifications for the Seven Mile Bridge over the Gardner River. The Bureau's plans designated grading and draining on an 18 feet 1930 standard roadway width. Concrete box culverts and corrugated metal pipe were designed for drainages; tile drain and rubble drains were planned for wet and swampy areas.

Following the advertisement for bids in the Rocky Mountain News, Denver, The Billings Gazette, Billings, Montana, and the Salt Lake Tribune, Stevens Brothers of St. Paul, Minnesota was awarded the contract with a bid of $140,126.65 or 73% of the engineer's estimate. The contractor, who was awarded the contract on August 5, 1931, set up camp immediately and began construction work on August 13.

Three camps were used for this contract. During 1931, the camp near station 55, or near Apollinaris Springs was used, then moving the camp to station 300 at Swan Lake Flats in October, 1931. For the remainder of the construction time, a camp near station 515 was used. These camps consisted of portable cabins positioned on wheels for cook houses, office and bunk houses, and tents to accommodate extra crews. The average daily crew working on the project was 57 men using the following equipment:

3 - "60" Caterpillar tractors

2 - Hydraulic Bodies

2 - Hydraulic Fresnos

1 - Concrete mixer

1 - Hydraulic Bulldozer

1 - Hydraulic scarifier

1 - Elevating Grader

14 - Teams with dump wagons

1 - 1-1/4 yard gas shovel

4 - 3 ton dump trucks

4 - 1 ton trucks

1 - Grader, 12' blade

1 - Compressor

1 - Small electric light plant [35]

One of the partners of the firm, C.R. Stevens, served as superintendent of the project. Using mostly long-time firm employees, he also hired common labor locally. The foreman was paid $140 per month, skilled labor, $100 to $140 per month, common labor, $55 per month. The contractor gave a $45 per month subsistence sum.

During 1931 season, grading began at a point south of Obsidian Cliff and in 2-1/2 months had progressed to station 245 near the crossing of the Gardner River, but cold weather forced the crews to move toward the other end of the project near Mammoth. Prior to shutting down for the winter, all concrete work had been done, the Seven Mile Bridge begun, some masonry work finished and the drainage projects completed as the grading progressed.

The contractor started the 1932 season on May 12 with shovel and dump trucks working in the Hoodoos. Extensive blasting was required to break up and loosen the huge wedged rocks, then more blasting was needed to break the rocks into manageable sizes for hauling. Grading continued on the project until August. During the 1932 season, the Seven Mile Bridge was completed, pipes, head walls, and rubble drains, were completed as grading permitted, and an old road was obliterated. The old road, from station 465 to station 496, required tearing out old retaining walls, cutting of the old shoulders, and hauling out the waste material. The new road approximately paralleled the old road.

Two concrete box culverts were installed, one 8' x 6', at station 64, the Obsidian Creek crossing and an 8' x 4' at station 369, the Glen Creek crossing. Corrugated metal pipes with masonry headwalls were installed over the other drainages. Tile and rubble drains and rock sub-base were installed in the swampy ground in areas of springs. The project required the installation of 1922 feet of tile drain and 5,955 feet of rubble drain.

The types of material the grading crews faced throughout the project were varied. From just south of Obsidian Cliff to near the Glen Creek crossing, the cuts were through solid rock, loose rock, gravel, muddy swamps and common earth. From the Hoodoos to the end of the project at the Mammoth Terraces, cuts were through solid rock and very large loose rocks, with some common earth and gravel toward the end. Since the Park required that all borrow pits should not be visible from the road, some difficulty was experienced in finding suitable material with a reasonable hauling distance. [36]

The engineering crews occupied three portable cabins built by the contractor at the National Park Service's Beaver Meadow maintenance camp during 1931, then moving to Mammoth Hot Springs until the end of the project. In addition to retracing the center line and cross-sectioning the entire project, staking culverts, and drains, the engineers placed concrete center-line markers at intervals of approximately one-half mile over the entire project. A light palliative oil treatment, 4,000 gallons per mile, was applied to the entire project to aid in the dust nuisance and serve as an interim measure until a surface course of crushed rock or gravel was applied. The project was completed by September 6, 1932 for a total cost of $136,810.94. [37]

Several landscape architecture issues were identified during 1932. During Landscape Architect Mattson's inspection of the guard rail between Mammoth Hot Springs and Norris in July, he objected to the use of the dark stain. The Bureau attributed the use of the stain as the result of competitive bidding, but he was willing to work with the Park to achieve a desired effect. After discussing the use of oil to thin the stain, Mattson was assured that the stain would bleach to a lighter shade. However, in discussing the staining of the guard rail at Madison Junction, he "asked them not to stain the guard rail at Madison Junction until it was complete and then use every effort to obtain the original desired color." [38]

Vista clearance and guard rail installation was also considered by the Park landscape architects in their July report:

| sta.93 | work will be done under road contract to provide turnout when waste material is cleaned up. |

| sta.122 | Road ditch to be filled making 10 ft. dalite available for distance of 100 ft. No guard rail required. Few trees to be selected and removed. |

| sta.125 | Dalite already available between sta. 124 and sta. 126 needs oil surface and 150 ft. guard rail. Some trees to be removed. |

| sta.150 - 151 | some trees to be removed-no turnout no guard rail required. Vista will be available while autos are in motion. |

| sta.160 | remove numerous matured trees at edge of meadow for vista. No parking required, no guard rail. |

| sta.173 - 175 | This location is on the outside of a curve. It would require considerable yardage to fill three feet deep and ten feet wide. Guard rail would be required. |

| sta.185 | Several dead trees and a few mature trees to be removed. No parking or guard rail. [39] |

Upon the completion of the Mammoth Hot Springs to Obsidian Cliff segment, the short steel Seven Mile Bridge which the new road bypassed was removed by Park crews then the old road obliterated. The new road location required the removal of 5,460 feet of telephone lines. The 18-wire system was relocated through a 16 feet right-of-way in a wooded area. [40]

In October, 1933, John McLaughlin of Great Falls, Montana, was awarded the surfacing contract for the 11.99 miles of road between Obsidian Cliff and Mammoth Hot Springs. Upon receiving the contract, McLaughlin set up camp about 600 feet to the right of station 520, a site which had been used by two previous contractors. McLaughlin purchased the frame buildings which the other contractors used for use as cook house, office, and bunk houses. He completed the camp by adding tents for use as additional sleeping quarters.

The crews began quarrying the widened heavy cut through solid rock in the Golden Gate between stations 418 and 421. The rock, obtained from the high cliffs, was blasted, put through a primary crusher and then stock piled to the left of station 409 at Swan Lake Flats. [41] The crews worked through the winter in order to avoid the traveling public during the visitor season. By the beginning of May, 1934, sufficient rock was stock piled and some surfacing had begun. By July 17, the project was complete.

The finished roadway had a 22 feet shoulder-to-shoulder width, a 4 inch base of 1-1/2 inch maximum size aggregate and 1 inch top of 1 inch maximum size aggregate. The earlier grading contract had graded the road on the 1929 standard, but on this project the super elevation on all curves conformed to the 1932 standard. The surfacing courses consisted of rhyolite. At the conclusion of the project, a palliative oil treatment was applied. A plant mixed oil course was scheduled for application during the summer of 1935. [42]

In October of 1934, Taggart Construction Company received the oiling and seal coat bid for $99,836. This project covered 36.29 miles of road, with 11.99 miles receiving a plant-mix oiled material and 24.29 miles receiving a seal coat. The contractor established his camp approximately 1000 yards left of the gravel pit which was to provide the surfacing material at station 255. A frame cook house was constructed, portable tents were used for bunkhouses and a portable building on wheels served as the office. The project required the services of about 65 men. A Pioneer Duplex crushing and screening plant was placed at the gravel pit which was approximately 1000 feet left of station 260. The crushed and screened material was stock piled nearby. [43] The project began on May 15, 1935.

Upon the completion of oil matting, the crews built masonry guard rail, performed cut slope treatment, cleaned up any slide material, obliterated old roads and borrow pits, placed top soil and planted approximately 275 trees of which 28 died. Parking areas were constructed near the Beaver Dams at station 100, at Appollinaris Spring and Roaring Mountain. The Beaver Dams parking was considered by the engineers to be a "pleasing and useful asset to the road."

The project, which extended from Mammoth Hot Springs to the Firehole Cascades was completed on September 30, 1935. With the exception for the needed construction and or/replacement on four bridges over the Gibbon River, "The smooth, wide highway, with easy curves and grades, should add greatly to the comfort and safety of the increasing volume of tourists who come to visit Yellowstone National Park each year." [44]

With the exception of bridge construction along this route, no major work was completed on the road until 1948 and 1949 when the road received another bituminous seal coat surface. The project, which was classified as a maintenance project and funded from Park funds, was awarded to Peter Kiewit Sons' Company of Sheridan, Wyoming, for a cost of $77,250.00. The park hoped that this treatment would extend the life of the existing pavement and lower the cost of maintenance on this road section. The crushed and screened material was stockpiled at locations along the route, however, the bituminous material was trucked in directly from a refinery at Cody, Wyoming. Most of the equipment and supplies were brought in from West Yellowstone or Gardiner, Montana. In order to transport the crushing and screening plant over the Madison River Bridge, the bridge had to be reinforced with the addition of eight temporary timber bents. The project was completed on August 2, 1949. [45]

The next major road project between Mammoth Hot Springs and the Firehole Cascades was the construction of the Norris Junction bypass, a project initiated by the National Park Service's Mission 66 program for FY65. The 6.32 miles long project channelized the intersection for the Grand Loop Highway and the Norris-Canyon Cutoff. The new alignment intended to provide a bypass of the Norris Museum and the Norris Geyser Basin and reduce the traffic congestion in that area.

The plans for this bypass were designed in the Region 9 Federal Highway Projects Office during the winter and spring of 1964-65. Both aerial and ground survey methods were used in siting the new alignment and automatic data processing equipment was used in its design. The mainline roadway was designed for a 38 feet graded width with 5-1/2 inches of base. The upper 1-1/2 inches of base were bituminous stabilized with a surface width of 30 feet. The two spurs road leading of the bypass were graded to a 32 feet width with a 5-1/2 inches base of which the top 1-1/2 inches were bituminous stabilized with a surface width of 24 feet. The shoulders were defined it cover aggregate resulting in a travel way of 22 feet on the main road and 20 feet on the spur roads. A 12 degree maximum curve, a 5.4% maximum grade, and minimum horizontal and vertical sight distances of 250 feet and 240 feet, respectively, were other design features.

The contract was awarded to R. J. Studer and Sons of Billings, Montana who submitted the low bid of $817,815.00. During May of 1966, subgrading began in an unstable, marshy area across from Elk Park, then moving on to a soaked peat bog near the Gibbon River. In addition to the grading operation, corrugated metal culvert pipe, vitrified clay culvert pipe, and perforated corrugated metal pipe underdrains were installed. Drop inlets, headwalls, and concrete curb and gutters were installed in October of 1966. By the end of October, 1966, the old road had been obliterated in the Norris Geyser Basin area, the areas of the old Gibbon River bridge, and the old Norris Junction. Seeding was done in one procedure with a 1,200 gallon capacity tank hydroseeder, seed, fertilizer, and green-dyed wood cellulose mulch. The one operation covered approximately 1/4 acre.

The guide posts treatment was changed from chemonite or greensalt to pentachlorophenol which produced a brown rather than green color. Other landscape details required the coloring of visible portions of concrete box culverts to be the same color as the curbs and gutters and, the removal of downed trees along part of the route. The crushed aggregate came from a pit sited to the left of station 1362+50 on Route 12, the Northeast Entrance road, the material came from an alluvial deposit and some from a highly disturbed rhyolite formation next to the alluvial deposit. A pit at Corwin Springs, Montana, provided the concrete aggregate and the cement came from the Ideal Cement Company at Three Forks, Montana. Almost all of the corrugated metal pipe, which was spot welded, came from the Bethlehem Steel Corporation. The contractor completed the project on November 7, 1966.

Upon its completion, the route now provided safer passage through this area. In the past, a common complaint and worry to Park officials was the reduced visibility caused by the steam blowing across the road from the geyser basin. The cars, which were pulled off on the road's shoulder for better viewing of the geyser basin, also caused a safety hazard. One recommendation the officials made at the end of the project was that the roadway receive a high type bituminous surface at some time in the future to replace the 1-1/2-inch thick plant-mix base which had been applied as a temporary measure. [46]

|

|

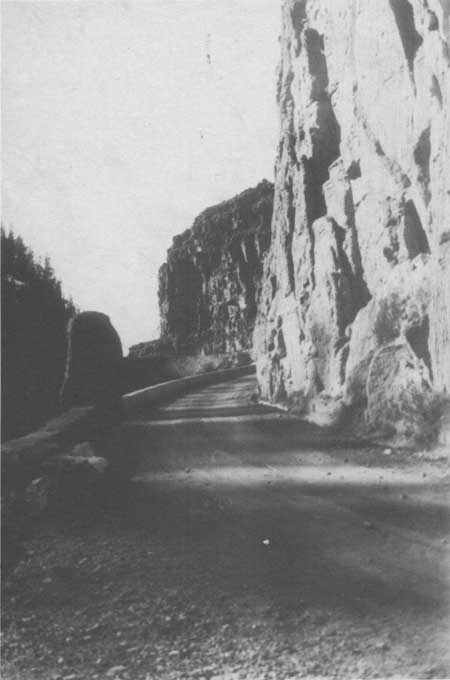

Golden Gate, early 1900s Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Golden Gate, early 1900s Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

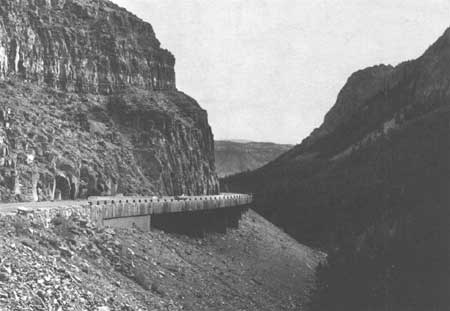

Golden Gate Viaduct, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

|

|

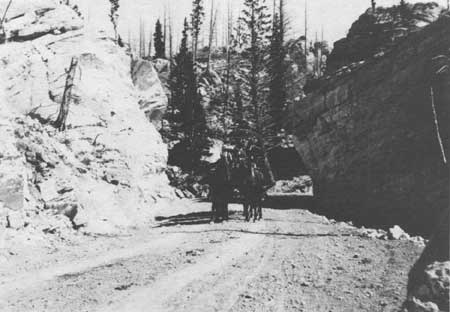

Buggy at Silver Gate in the Hoodoos, ca. 1895 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

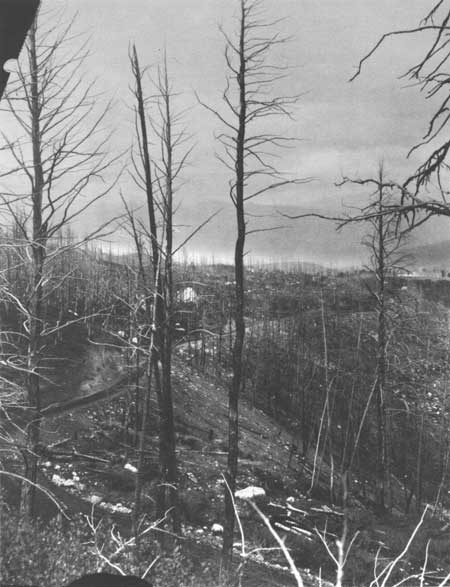

Road Below Golden Gate, ca. 1900 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Seven Mile Bridge, ca. 1900 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Seven Mile Bridge, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

|

|

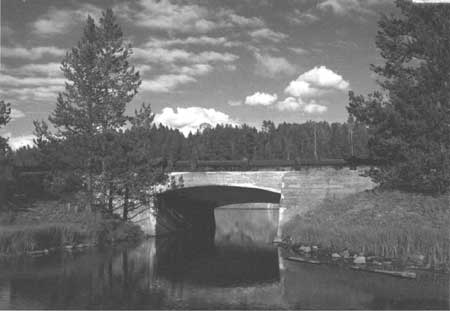

Obsidian Creek Bridge, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

|

|

Detail of Obsidian Creek Bridge, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

|

|

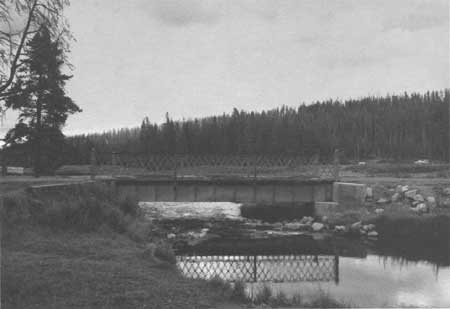

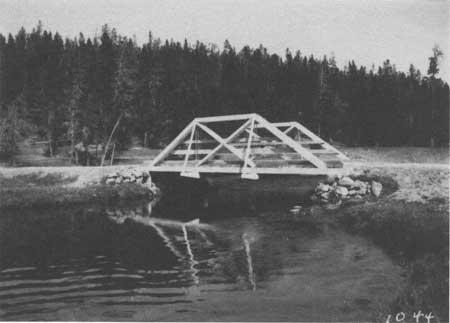

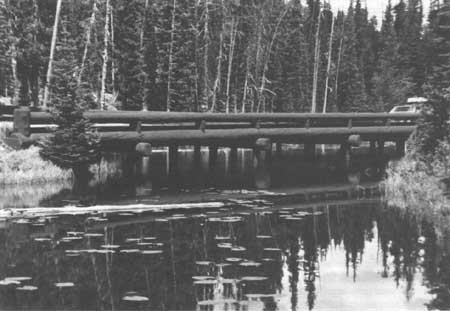

Gibbon River Bridge, near Norris Junction, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge, near Norris Junction, 1953 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

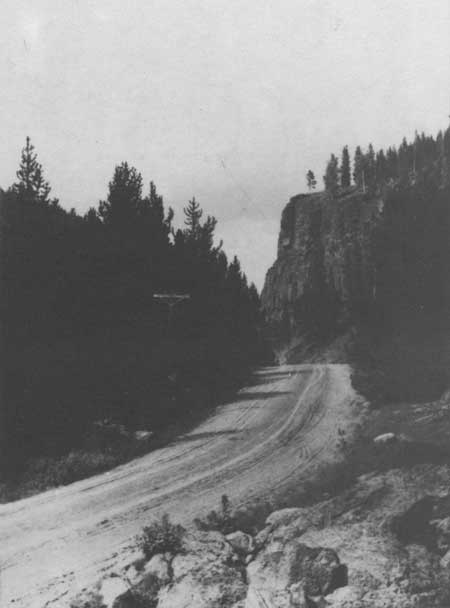

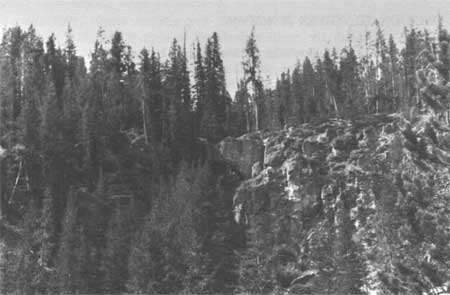

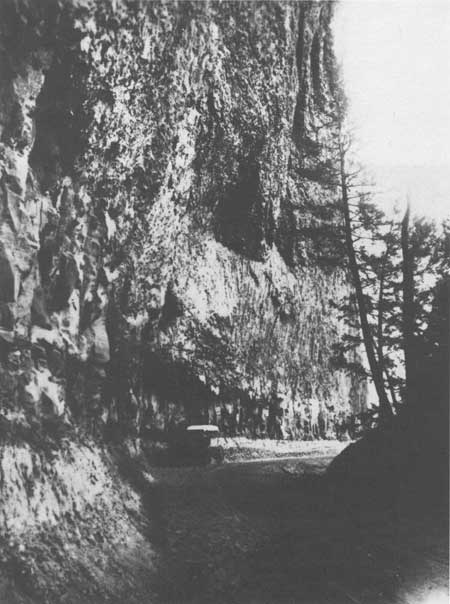

Road near Obsidian Cliff, 1905 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

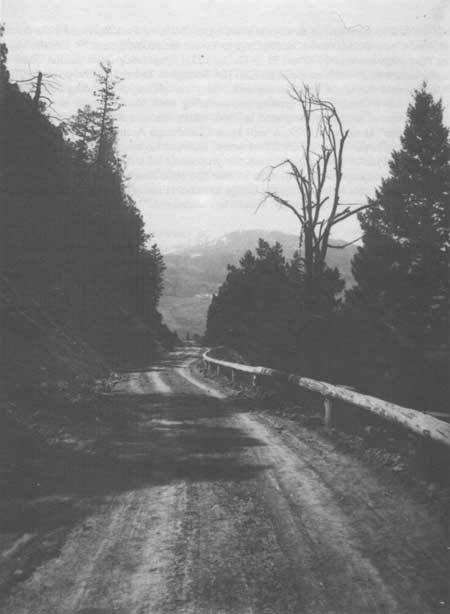

Road near Norris Soldier Station, ca. 1900 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

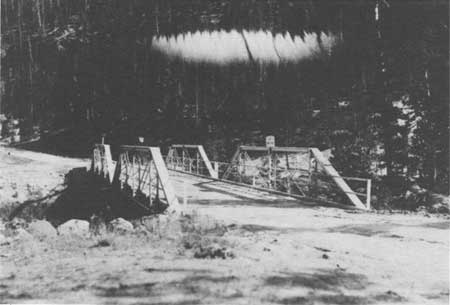

Gibbon River Bridge near Beryl Springs, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

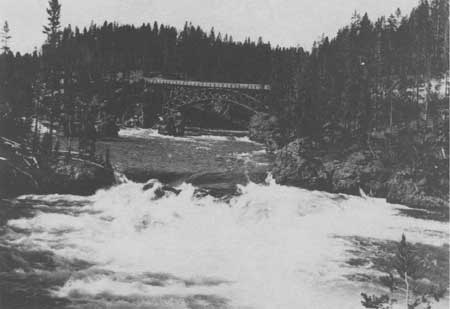

Gibbon River Bridge, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Norris to Madison Junction Road, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge, near 7 Milepost, Norris Junction to Madison Junction, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge, 6 Milepost, Norris Junction to Madison Junction, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge below Wylie Camp Lunch Station, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

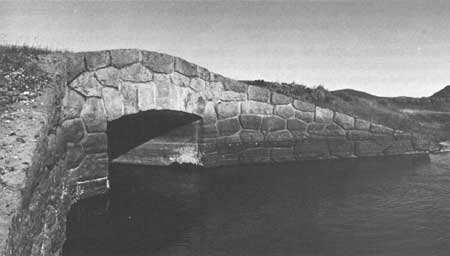

Gibbon River Bridge near Madison Junction, 1912 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge near Madison Junction, 1961 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge, 1917 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge near Madison Junction, 1917 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge, later placed over Firehole River on Fountain Freight Road, 1917 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Road near Gibbon Falls, 1908 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

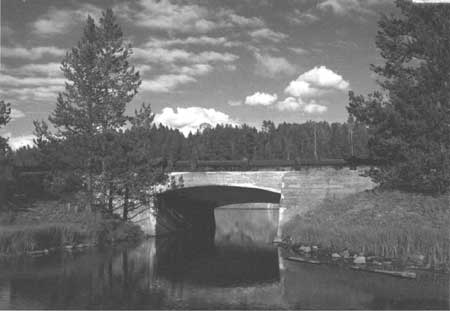

Gibbon River Bridge in Gibbon Canyon, 1953 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon Canyon Road, 1953 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

|

|

Gibbon River Bridge, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

MADISON JUNCTION TO OLD FAITHFUL SECTION

As early as 1873, a road had been completed from Virginia City, Montana to the Lower Geyser Basin, via the Madison Canyon. Gilmer Sawtell, who catered to park visitors at his hotel on Henry's Lake in Idaho, built the west entrance road and named it The Virginia City and National Park Free Road. [47] Four years later, the second superintendent of the Park, Philetus Norris proposed in his first report to the secretary of the interior, the construction of a wagon road connecting the "wonders" of the park which included a route connecting Lake Yellowstone through the geyser basins and exiting on the west side. As a result of the Nez Perce conflicts during the summer of 1877, the construction of a road from the headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs southward to the Lower Geyser Basin became the highest priority construction project. This completion of the section of road would facilitate the movement of the military from Fort Ellis, Montana to Henry's Lake in Idaho or Virginia City, Montana, and of course, be used by the ever increasing number of visitors to the park. [48]

In 1880, improvements were made to the Firehole River Road including opening a road into the midway geyser area. [49] The following year, two footbridges were constructed over the Firehole in the Upper Geyser Basin. The next major work took place after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers assumed responsibility for road construction in the park in 1883. At that time, the roads in the park were described as "barely passible and are daily growing worse. Just Sunday a lady was thrown out of the carriage and badly hurt at Fire Hole River. Between the 2 fords on Gibbon River, my wagon was turned over sideways and my wife thrown out. . . . The roads are terribly worn down on one side which makes it difficult to keep in a wagon." [50] Under the direction of Lt. Dan Kingman, a new bridge was built over the West Fork of the Firehole and some stretches of corduroy road were repaired and ruts filled. Finding the Mammoth Hot Springs to the geyser basins the most heavily traveled in the park, he also noted that it had the most serious natural obstacles and thus the "worst" in the park.

Kingman constructed a new road between the Firehole River and Upper Geyser Basin, as the old, poorly located road would be very costly to improve. The "unnecessarily long" and old road crossed a "kind of geyser swamp" in some places and crossed soils of a "black obsidian sand" in others. [51] As the road neared the Upper Geyser Basin, the alignments of the old and new roads were almost the same. The new route, which cost a total of $6,042.53, reduced the three to four hour travel time from the Marshall Hotel at the Forks of the Firehole River the Upper Geyser Basin to one hour. Kingman described it as "well built" and said that the bridges and culverts had "substantial character." He further describes it as "sensibly level, and as the roadbed is mostly composed of gravel that packs well, it is a very pleasant road to drive over." [52]

The first trestle bridge built in the park crossed the Firehole River above Hell's Half Acre. Kingman felt that this bridge was well suited to the unusual conditions of the locality, "enormous quantity of hot water that this river received, it never carried any ice, and as its discharge is remarkably uniform (there is hardly a difference of a foot between high and low water) it bears little or no drift wood." The trestle bridge, costing $400, was covered with 4-inch hewed planks. [53]

In 1889, 3.5 miles of new road had been built along the Firehole River above the Upper Geyser Basin and two bridges, in addition to the trestle bridge had been built—a two span of 36 feet each over Firehole River, no truss and a one span of 38 feet over the Firehole River, no truss. [54] In 1892, Lt. Hiram Chittenden urged the rebuilding of "the worst, most tedious, and least interesting drives in the park," the road from the Gibbon Falls to the Lower Geyser Basin. [55] In 1894, a new road was completed from a point on the old road near Gibbon Canyon south across the flats toward the Firehole and also connecting with the road west down along the Madison River. At the same time, a bridge spanning the Firehole River near Excelsior Geyser was built permitting teams to cross the river at this point and join the main road in the edge of the woods opposite. [56] The next year the new road had been extended to Nez Perce Creek. In 1897 a new bridge was built over the Firehole near the Riverside Geyser and a new footbridge built over Firehole River near Biscuit Basin. [57]

During the first few years of the 20th century, several bridges were built along this section. In 1903, a new steel truss bridge, whose material came from the American Bridge Company, was built over the Firehole River, 1/2 mile above Excelsior Geyser. [58] More bridge construction and reconstruction occurred during 1905 and 1906. During the 1905 construction program, a steel truss bridge over Nez Perce Creek and two wooden bridges were reconstructed, one on the old road from the Lower Geyser Basin to Excelsior Geyser, and the other just above the Upper Geyser Basin. During 1906, the wooden bridges over the Firehole River on the old freight road near the Fountain Hotel and over the Firehole River above the Upper Geyser Basin were reconstructed. "An attractive footbridge of rustic design was constructed over the small stream between the Castle Geyser and Old Faithful Inn." [59]

In 1907, the Army engineer supervised the repair of many of the park's wooden bridges and the replacement of some bridges with culverts. On this road section, a new wooden abutment was built at the bridge over the Firehole River on the Fountain to Upper Geyser Basin road and tile culverts were laid at 7-7/8 miles on the Norris to Fountain section. [60] The following year, new decking was laid on two bridges spanning the Firehole River, one crossing being near the Riverside Geyser and the other on the Upper Geyser Basin to West Thumb at the junction with Spring Creek. One 12-inch corrugated sheet iron culvert was placed at 9-1/2 miles on the Norris to Fountain road. [61]

In 1909, a bridge inspection was done for all of the Park bridges. The bridges on this section of road were described as follows:

Bridge No. 9, across the Firehole River at Riverside Geyser, Upper Geyser Basin. The present bridge consists of a two-truss wooden span on wooden piers and abutments. This bridge is entirely too light for the service required at this point. It is located at one of the most important points in the Park, and in addition to the vehicle traffic, is at times loaded with sightseers viewing the Geysers. It is recommended that, owing the the importance of the bridge, and its location, it should be made an attractive appearing structure, and further recommended that two 32' plate girder spans with curved effect underneath be used resting on concrete piers and abutments, and that the roadway be 20' in width so as to accommodate the sightseers without interference with the vehicle traffic.

Bridge No. 8, across the Firehole River at Hell's Half Acre, near Excelsior Geyser. This bridge was built in 1895, of white pine lumber, and consists of two spans with one pier in the center of the stream and two abutments. It is now in a decaying condition and its factor of safety is so much reduced that it should be removed at once. It is recommended that it can be replaced by two 50' low truss, pin connected steel spans and concrete pier and abutments.

As part of the inspection report on the bridges in the Park, it was recommended that plans be drawn for a reinforced concrete bridge to be constructed over the Firehole River near Riverside Geyser. Capt. Wildurr Willing of the Corps of Engineers felt that since this was one of the most visited areas in the park, it was necessary that the bridge be of an aesthetic design. [62] However, because of costs, a 65 feet steel arch bridge was built was built by the Minneapolis Steel and Machinery Company in 1911. As late as 1923, the 1911 bridge was still in use. [63]

Not many major changes or improvements were made to this road section after the Army left the Park and the newly created National Park Service assumed the road construction program. The new director did suggest the completion of the Firehole Cutoff road. [64] The 4 mile long freight road, which paralleled the main road between the Fountain Soldier Station and the Excelsior Geyser, was closed in 1917 due to its unsafe condition of the wooden truss bridge over the Firehole River about 1 mile from the soldier station. A new 50 feet bridge was built as a replacement and a 40 feet bridge over Nez Perce Creek was reconstructed. [65] And in 1921, a new foot bridge was constructed over the Firehole River near Castle Geyser. [66]

Prior to the next major construction program initiated after the Bureau of Public Roads took over the road work in Yellowstone in 1926, the Firehole River Road south of the Firehole Cascades for 3.5 miles was widened for two way traffic. [67] The work began in May, 1925 in the immediate vicinity of the Firehole Cascades and a camp was set up near the cascades. By the middle of July, 5,160 cubic yards of excavation had been removed by hand and team labor. Of the total, 4,400 cubic yards was of solid rock. The crews installed approximately 150 feet of drainage culvert. The cost of the project was approximately $6,000. In 1926, Director Mather reported that the work along the Firehole River between Madison Junction and the Firehole Cascades was "constructed on the highest standards of any used in the National Park Service" as "the beauty of the canyon justifies the very great attention that is being given to details of wall and fill construction." [68] The 1926 project, which involved widening a 1.5 miles section of the road in very narrow places and new construction for 1.5 miles, had originally been started by the Army engineers, but abandoned in 1916. The project required 1 foreman, 1 cook, 1 flunkey, 1 compressor operator, 2 Jackhammer men, 1 powder man, 1 grade man, 14-horse teamster, 2 2-horse teamsters, 1 axe man, 1 blacksmith, 6 laborers, and 3 teams. The project required the excavation of 360 cubic yards of common material, 820 cubic yards of loose rock, 2,945 cubic yards of solid rock and the installation of 120 linear feet of 12" C.M.P. culvert in place and 24 linear feet of 18" C.M.P. culvert in place. All excavated material was used on the project. "Neither the amount of material nor the nature of the country would permit fills on a naturally stable slope and all embankment was constructed with hand placed fill or rubble wall on slopes of 1/4 to 1/2 to 1." [69]

Work also began on a new bypass road at Fountain Paint pot as the old road was widened and improved to become a short loop road. The necessary fill material was hauled from the cut at the 7 milepost, about 1-1/4 miles distant. About half of the construction in this section was through sandy material which required a binder to create a stable surface. A sharp curve above the Firehole River Bridge at Excelsior Geyser was widened by the excavation of 600 cubic yards of solid rock. The borrow for the material on this project came from a pit near Firehole Lake. The project was finished in July, 1930. A total of 2.16 miles of road had been built and 196 linear feet of 18" CMP culvert had been installed. [70]

7Shortly thereafter, the crews began lessening the curvature and widening the grade on a sharp curve at a point five miles north of Old Faithful. This project required the hand excavation of about 475 cubic yards of material which was then used to widen the grade from 18 to 24 feet, both at the curve and a distance of 200 feet on either end. All of the excavation was through a sand-clay formation, thus no additional surfacing was required. It was finished with an application of oil. [71]

In 1930, the realignment of the Norris Junction to Madison Junction road resulted in two steel bridges across the Gibbon River approximately 9-1/2 miles below Norris Junction being abandoned. It was proposed that both would be removed, however one bridge, which served the old stage road (Mesa Road) to the Firehole Cascades, was still needed as diverted traffic used this route while the new road was being completed. The other Gibbon River Bridge, a steel arch bridge with concrete floor, constructed in 1913 at a cost of $4,010, was dismantled and reassembled over the Firehole River on the Fountain Freight Road. This relocated bridge replaced an unsafe timber bridge. This bridge has since been removed. [72]

In an inter-bureau conference held in San Francisco in 1931, the National Park Service requested a reconnaissance survey be completed for the road between Firehole Cascades and Old Faithful. The average daily traffic during that period was about 600 vehicles per day with about 10% of the total being trucks and busses. The survey found that the first 2.5 miles from Madison Junction to the Firehole Cascades, which had been reconstructed by day labor of the National Park Service and surfaced by the Bureau of Public Roads in 1931, to be in satisfactory condition. Thus most of the survey was for the remainder of the road. The Park requested the feasibility of rerouting the main road via the Firehole Lake, the east end of Biscuit Basin and Black Sand Basin. They also felt that if this was not desirable then they wanted loops built in these areas. The recently built bypass of the Fountain Paint Pot proved to have reduced the interest at this point, thus the Park desired a rerouting producing a closer approach. Within 10 days, the survey crew recommended many slight variations from present alignment, flattening of curves, reducing curvatures and widening the present road. It was estimated that approximately 10 culverts would be needed for every mile. The width of the road from shoulder to shoulder should be 28 feet for the main roads and 22 feet shoulder to shoulder for the proposed loop roads. The four bridges on the project were considered too narrow and too light of construction to carry the average daily traffic load, and therefore should be replaced. [73]

The location survey for this project was completed in 1932 and the Morrison-Knudsen Company, of Boise, Idaho was awarded the grading contract on July 17, 1934, for the low bid of $188,216.10. The contractor began establishing his camp at Goose Lake on July 19, 1932. The camp had frame buildings which facilitated 125 men. Family members were provided for at a camp just across the creek from the main camp. The engineers camp, which consisted of two 16' x 16' portable houses and two tents, was located at Riverside Geyser. Work began immediately and closed for the season on December 26 with 84 percent of the project completed. The 1935 season began in May and with 95% of the project finished by September 9 when the contractor closed down for the year.

By the end of the 1935 construction season, the road had been graded to a minimum width of 28 feet at the recommendation of the National Park Service. The Bureau of Public Roads standard for that time was a 26 feet roadway, shoulder to shoulder. The bridge construction was handled by separate contracts. All cross and side drainage structures were corrugated metal (1,898 linear feet) and Vitrified Clay Pipes (4,254). Since many of the drainages are through areas of unusual chemical composition, vitrified clay pipe was preferred. The 271 cubic yards of rock for the masonry work was obtained at a quarry at a point where the Mesa Road leaves the Grand Loop Road between Gibbon Falls and Madison Junction. Because of the superior condition of the subgrade, it was deemed possible for traffic to move over the road for a season or two until the final surfacing is done. [74]

Concurrently with the road construction project, a bridge contract was awarded to McLaughlin Construction Company of Livingston, Montana, for the construction of the Nez Perce Creek Bridge, the Firehole River Bridge and a foot bridge over the Firehole River at Excelsior Geyser. Work began in 1934 and the bridges were completed on September 6, 1935. Following the completion of the bridges, the Park felt that "great improvements" had been made in the roadways. The use of four to one slopes on low embankments was preferable, however, that combined with not diverting branch streams left:

some undesirably conspicuous culvert headwalls especially on the road recently completed between Madison Junction and Old Faithful. It is believed that a change in design of culvert headwall is desirable and that an improvement in appearance can be readily obtained. One plan would be to move the headwalls closer to the road shoulder, to bevel the projecting corner, and to provide 90 degree wingwalls on the same slope as the embankment. Another method would be to bevel the end of the culvert and protect the bank by hand placed embankment or by masonry laid flush with the surface of the embankment. While the masonry of large bridges adds to the attractiveness of the roadway it seems to be undesirable to make the headwalls of small culverts conspicuous and the more invisible they can be the better the appearance of the road side. [75]

Another landscape issue identified with this section's bridge work was the type of curbing desired. The Park felt:

that a concrete curb is more serviceable than a masonry curb. It is, however, suggested that the appearance of wingwalls would be improved by making the wingwalls all of masonry including a masonry curb rather than introducing a concrete curb as a portion of a masonry wall. A single course of masonry above a concrete curb does not give the appearance of being adequately bound into wall. [76]

Both the newly constructed Nez Perce Creek Bridge and the Firehole River Bridge have the combination of the concrete curb with the masonry walls.

The next major project on this road section was the relocation of approximately 2-1/2 miles of road between a point on the Grand Loop Road immediately north of Madison Junction to a point on the Grand Loop Road near the Firehole Cascades. The old road, which is along the Firehole River through a narrow canyon, was first constructed by the Army engineers, but abandoned in 1910 because of construction costs and the very heavy character of the work. In 1925, National Park Service day labor forces resumed construction on the section and it was eventually surfaced by the Bureau of Public Roads in 1931. The 1938 Preliminary Location Survey proposed the construction of a new bypass road to alleviate the serious bottleneck imposed by the narrow road through the Firehole Canyon. The engineers specified that the new bypass be built on the same standards as the rest of the Grand Loop Road. Upon completion, the old road could be used as a scenic drive. [77] This report resulted in preliminary plans, however, the construction did not occur for several years. In 1949, a 38 miles chip sealing project on the Mammoth Hot Springs to Firehole Canyon road and a grading and base surfacing project in the Firehole Canyon began. [78]

Many improvements, such as widening the roadways and bituminous surfacing, were made on the Madison Junction to Old Faithful section during the 1960s. A number of remanents of old roads were obliterated and the scenic loop roads were resurfaced and improvements made to the shoulders. Rock work was repaired after the 1959 earthquake. [79]

|

|

Along Firehole River, ca. 1900 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Firehole River Bridge No. 5, North of Old Faithful Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Firehole River Bridge, 1913 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Firehole River Bridge, 1931 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Nez Perce Creek Bridge, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

|

|

Firehole River Bridge, near Morning Glory Pool, 1989 Courtesy Historic American Engineering Record, Jet Lowe, 1989 |

OLD FAITHFUL TO WEST THUMB

Army Engineering Officer William Craighill became the first person to survey the Old Faithful to West Thumb route. Not knowing the precise route that the road would take, Craighill had the crews working from each end. Before the road was completed, Craighill was replaced by a significant figure in the park's history, Lt. Hiram Chittenden. One of Chittenden's first assignments was to complete Craighill's project, the construction of the road from Old Faithful to West Thumb road. In 1891, Congress required that the route be built by the shortest practicable route. [80]

Thus, Chittenden's recommended route, which closely paralleled today's road, did not skirt Shoshone Lake as Captain Kingman proposed, but instead crossed Isa Lake and crossed the Continental Divide twice. According to a Yellowstone National Park historian, Aubrey Haines, Chittenden discovered that the crew on the Old Faithful end were following the old Norris trail. "That was Mr. Lamartine's idea of locating a road—to follow a trail with all its irregularities and excuses of gradients, regardless of what improvements could be made by something of a survey." Haines wrote that "Chittenden found it necessary to do the locating himself, working alternately at the two ends of the line with a hand level, a five foot staff, and the assistance of two laborers." [81] The road, completed during the summer of 1892, is one-third shorter than Kingman's proposed route via Shoshone Lake. [82]

In 1891 or 1892, a pole bents and stringers trestle bridge was constructed to span a ravine 1-1/2 miles from West Thumb and the Log Cabin Bridge across Herron Creek was built. The Log Cabin Bridge consisted of "two piers built up of logs resembling a log cabin, hence its name. There are also two wooden abutments. The spaces between the piers are spanned by stringers of white pine logs." [83]

The Grand Loop was finally completed in 1905. In 1908, a new, small bridge was built on the flat near DeLacy Creek and repairs were made to the bridges over Herron Creek and DeLacy Creek. [84] In 1909, Engineering Officer Wildurr Willing, made a thorough inspection of the bridges in the Park. He recommended that the trestle bridge, 1-1/2 miles from West Thumb, be replaced with a low truss, pin connected steel span, 60 feet in length, which would rest on concrete abutments. He called for the replacement of the Log Cabin Bridge with a 60 feet steel arch span with steel approaches at either end. Due to the fact that at one end of the bridge the road makes a sudden turn, that end had to be widened "so as to permit the four-horse teams to swing onto the bridge with ease." Another trestle bridge, 60 feet in length and constructed of pole bents and stringers, which spanned a ravine 1 mile west of West Thumb, was scheduled to be replaced by a 4 feet culvert pipe. [85] It was replaced in 1913 by a concrete culvert and earthfilled wooden crib. [86] In 1912 a road assessment was conducted to determine the suitability from an engineering standpoint, of the system for the introduction of automobile traffic in the Park. The Army Corps Officer Captain Knight, concluded that it would be better if the existing system were reconstructed than creating a separate system for motorized vehicles as some had suggested. Not much work was done on the Old Faithful to West Thumb Road but a 25 feet long bridge had been constructed in 1911 (exact location not known). [87] In 1915, three concrete culverts from 4 to 6 feet spans and been built along Spring Creek and the foundation for three more, plus several galvanized culverts had been put in along the road segment. These replaced older wooden ones. [88]

In 1926, a Park report suggested that the wooden bridge just south of Old Faithful be replaced with a concrete structure and that all of the Dry Creek culverts have their capacity increased. The report also called for the installation of metal culverts for that section of the road. [89]

Intensive reconnaissance surveys of this segment were completed by Worth Ross in 1927 and by A. C. Stinson in 1934 at the request of Superintendent Roger Toll. Toll urged for a speedy completion of the survey with expectations of going into construction the following year. Records for 1934 recall that this segment, which was, and is, an integral part of the Grand Loop system, was the "lowest type and poorest main road in the Park." [90]

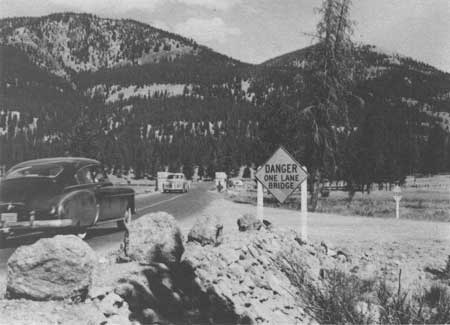

The Bureau of Public Roads engineers felt that the road was far below the standards of the roads elsewhere in the Park. During 1934, the road was being traveled by approximately 250 cars daily, whereas the approximate daily use for other segments was 500 cars daily. These figures were based on records of previous years indicating 50,000 cars entering the park during the 100-day season. Officials felt that the low usage of this segment was no doubt due to the one-way traffic regulations and the poor condition of the road.

A $10,000 allotment for the 1934 survey was approved; the survey began July 5, 1934. The 15-man crew completed the staked lines survey October 22, 1934. Later, an additional $4,000 was approved for the survey project. The surveying crew found the crooked and narrow one lane road following, "most of the devious windings of the water courses, which it employs in the ascent to and descent from the two crossings of the Continental Divide. The road employs a great many sharp curves and a few sketches of excessive grades . . . ." [91] The road width varied from 12-15 feet to 18-20 feet. The wider width sections were found in the flatter country and also at the beginning of the ascent to Craig Pass which also has some of the rockiest sections of the route. Less rocky country, but very crooked alignment was found in the lower section of Dry Creek, while the upper section of Dry Creek was described as "rolling hilly country of less rugged nature." The descent road from the second Continental Divide crossing to West Thumb ranged from gentle to very steep slopes as one neared Yellowstone Lake. The survey team reported that the earlier work had been designed to incorporate a "fine view" of the Yellowstone Lake at one of the very sharp curves and further down the road, an overlook was built for a view of Duck Lake, a spring-fed lake lying between the bluffs and Yellowstone Lake.