|

YELLOWSTONE

The History of the Construction of the Road System in Yellowstone National Park, 1872-1966 Historic Resource Study, Volume I |

|

|

Part One: The History of the Construction of the Road System in Yellowstone National Park, 1827-1966 and the History of the Grand Loop and the Entrance Roads |

CHAPTER XVII:

HISTORY OF WEST ENTRANCE ROAD

The first West Entrance Road, built by Gilman Sawtell, originated in Virginia City, Montana, and reached the Lower Geyser Basin by way of the Madison Canyon in 1873. Sawtell, the owner of a hotel near Henry's Lake in the Idaho Territory, named the toll-free road, The Virginia City and National Park Free Road, in order to differentiate it from the North Entrance toll road. [1] But, by 1877, the road was a barely passable road as noted by a visitor

A mile further on we come to vast quantities of fallen timber and we find our progress impeded to such an extent that we are compelled to call our axes into regulation, and cut our way for more than a mile when we again find open timber. [2]

In 1878, Philetus Norris had the road along the Madison River to the western boundary in his improvement program which included widening of the grades. But two years later, Norris was approached by O. J. Salisbury, a partner in Gilmer & Salisbury Company, mail contractors, to find a new coach and mail route for the west side. The existing route along the Madison River, which required much bridging, was impassable most of the year and many considered the route dangerous. After two days of exploration, an acceptable route, which cut south from the Madison River at Riverside, was found. Salisbury left men to construct a mail station at the Riverside cutoff, while he proceeded east to secure his mail contract. Norris, who once considered the mountainous area south of the Madison River inaccessible, was surprised to find "a dry, undulating, but beautifully timbered plateau, allowing a judiciously located line of wagon-road with nowhere an elevation much in excess of 1,500 feet above the Forks of the Fire Hole." [3] This route, which was shorter by six miles than the Madison Canyon route, would be cheaper to construct and maintain and also would open up new observation points for scenic and geologic interests. Traveling through the beautiful pine forests on an August trip to the West Entrance via the new route, Norris commented that this dry route was preferable to the often snow-covered and flooded canyon route. He felt that this would be the preferred route, however, the other, if necessary, could be used for part of the summer. [4]

Patrick Conger, Norris' successor as superintendent, accomplished very little in new road construction, but he did improve the older Madison River route which Norris bypassed after the plateau route was built. Conger found it necessary to undertake heavy grading work along the river route to the Firehole Basin. He described the canyon as "difficult and rough, involving the fording of the streams five times in the short distance of about 10 miles. The Madison River at this point is a broad and rapid stream, and except in time of low water, these crossings are both difficult and dangerous." The superintendent estimated that at least $15,000 would be needed to construct a good road. [5]

By 1900, the route across the plateau joining the Grand Loop at Nez Perce Creek was abandoned. [6] In 1896, the Army engineers worked on the West Entrance Road and built a bridge over the only crossing of the Madison River. [7] Prior to Hiram Chittenden's transfer to Mount Rainier, the Army engineer noted that the most western section would need to be changed to meet the proposed location of the railroad terminus and the proposed hotel planned for a site at Riverside, about four miles within the western boundary. In 1908, considerable work was done to this section, including crowning the road and adding large amounts of clay to the sandy soil. Many large rocks were removed on the section of road west of the Madison River Bridge where the road was widened and crowned. The swampy areas on the north bank of the Madison River were raised, widened and surfaced. [8]

During 1912 and 1913, the road was widened from 12 to 18 feet and it was surfaced with gravel. The next year, 1914, the crew which was camped about 2 miles from the western boundary, finished the grading, rolling, and crushing to prepare for an oil finish the next spring. The use of a small, No. 3 oscillatory crusher on a very hard rhyolite rock made it a very slow process. Another crew, camped at the Firehole Junction, cleared and widened the road between the 9 and 13 mileposts. Other widening and about 300 yards of alignment to reduce grades and improve the appearance occurred during 1914.

The president of Yellowstone Western Stage Company, F. J. Haynes expressed concern that the road would not be in condition to accommodate both wagons and automobiles in time for the expected surge of visitors prompted by the Panama-Pacific Exposition to be held in San Francisco in 1915. In addition, Haynes was opposed to the construction of a hotel at the western entrance to the Park. [9] The Army engineer responded to the possibility of both types of traffic on the West Entrance road

Whether the road will be safe for such combined use of vehicles is an entirely different question, and one that seems to me much more dependent upon whether or not animals become frightened than upon the condition of the road. On the whole this section of the road has less dangerous embankments than almost any other section of equal length in the park. However, there are a number of places where animal drawn vehicles may go over embankment should the teams become unmanageable and get away from the drivers. I doubt very much that such combined use would be safe with an practicable width of road that could be built in this section. This is taking into consideration the fear the team may have of automobiles, and not the width and surface of the road which I think ample, provided teams can be trained to allow such passing or separate roads assigned for each class of traffic. [10]

In 1916, the entire road section between West Yellowstone and Madison Junction was widened and graded. For the first 5 miles west of the boundary, oil macadam surfacing for the 18 feet width was completed. For the next 2-1/2 miles, a crushed-rock sub-base, 5 inches deep and 10 inches wide was prepared for an oil finish. [11]

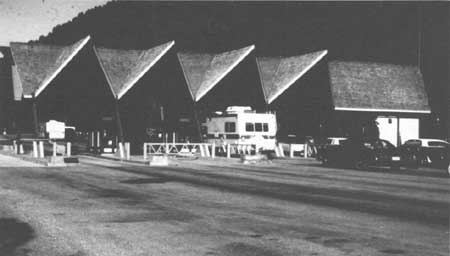

In 1924, a combined checking and ranger station was constructed with park funds for the West Entrance. The log-trimmed building was the idea of the Chief Ranger, who also supervised its construction. [12]

During the 1930s, many improvements were made to this road section. In 1930, more road oil was mixed with the existing surface, mostly obsidian sand mixed with road oil, to make a fairly good temporary oiled road. A few years later the road was given a crushed rock and oil finish. [13] Also during 1939, a temporary wye was constructed at Madison Junction. The wye junction was given a palliative treatment, spraying a coating of oil on top of the loose road material after the surface had been smooth with a blade grader. Later this method was improved by providing a light processing of about 1 inch of the natural top material with sufficient oil to form a 3/4" consolidated mat. Most of the West Entrance Road received the improved treatment. [14]

The Bureau of Public Roads engineers found the route to be the most direct and best between the junction and the boundary, but many of the curves too sharp for safety and the alignment unnecessarily sinuous for the topography. The road width ranged from 18 to 24 feet. The one Madison River crossing was bridged with a narrow steel truss structure consisting of two 80-feet spans placed on concrete abutments and steel encased concrete piers. The lightweight constructed bridge had a width of 16 feet making it totally inadequate for the 1930s traffic. Nearby, the engineers found evidence of an earlier bridge, rock crib foundations.

After concessions by both the Bureau and the National Park Service's Branch of Plans and Design, an agreement was reached on the new line which followed the old road closely and a new configuration at the wye junction. The old narrow concrete bridge near the wye was to be replaced. The north leg of the wye was planned to be located "considerably higher than the present road in order to develop an overlook on the forks of the rivers and the historic camp site." The landscape architects insisted that "care was taken not to scar the rockslide by excavation and to extensively incorporate the present road within the construction limits of the proposed line." A section of the old road was incorporated into a parking area for fishermen and for viewing the river. On a section of the road, old established fill slopes to the river were not disturbed. [15]

On different sections of the road, the new road departed about 400 feet to the right from the old road, eliminating three curves, and the new road was 350 feet to the left reducing the angle of curves considerably. As the road approached the checking station, the width was enlarged from 26 feet to 80 feet to provide space for 4 four lanes of traffic.

The new road was designed during 1934 and 1935 "to the standards then being used by this district, which at that time had just adopted the spiral but had not yet adopted the rates of super elevation and widening now in effect nor the still flatter back slopes now required and which still used the profile grade as center line elevation on all sections." The road was designed with 26 feet width, which was standard for all entrance roads. Other design features were as follows:

Revisions in alignment were made in a number of cases to reduce curvature rates to less than 5 degrees per hundred feet of distance, at which rate spiralling begins. At Madison Junction, where curvature was sharper, revisions were made to permit introduction of spirals, though it can probably be considered satisfactory practice to eliminate this complication in low-speed areas such as junctions.

Cut and fill slopes were designed in all cases as flat or flatter than required to conform to the standards shown on the sheet of standard sections in force in 1934; these varied, for cut slopes, from 2:1 in low cuts in common material to 1/4:1, in solid rock cuts; and, for fill slopes, from 4:1 to 1-1/2:1, depending on the height of the fill.

Cut slope treatment based on the same standard sheet was estimated for all cuts of whatever nature emerging in common material. Ditches along the road were designed on 4:1 slopes, from the road shoulder to the ditch bottom, to depths of 1 to 2 feet depending upon the drainage conditions at the particular place; where deeper ditches were required but deemed inappropriate, tile drain was provided for additional drainage. In one or two cases, as a further protection from surface seeps, a protection ditch was provided. In rock cuts, where feasible, ditch depths and widths were reduced, as indicated as permissible on the standard sheet, in order to save quantity. [16]

The only major structure constructed was the Madison River Bridge. All of the drainages were handled with corrugated pipe culverts, some with standard masonry headwalls. The materials for the concrete aggregate and the masonry work were mostly found in the project area. [17]

After the war, 1946, extensive work on done on this section. Most of the shoulders and slopes along the entire road had to be repaired and some resurfacing was done. Much of the damaged, broken or decayed log guardrail was replaced on this project. [18]

In 1955, just before the MISSION 66 program began some leveling and resealing was done to part of this road section to prolong the life of the road and reduce some maintenance. Large sections of the road had cracking and water had reached the base. At the same time, some of the 18" x 30' culverts were replaced. [19]

As part of the MISSION 66 program, grading and stabilized base construction was completed under three contracts covering 1958-1961. The 1958 contract included the construction of a new Madison River bridge. In order to insure a "more permanent dusk colored effect" of the concrete, the proposed formula of 1 pound of black mineral oxide was changed to use 1.5 pounds per sack of cement. "Previous experience proved marked bleaching by the sun when the proposed formula was used." A change in the concrete curb and gutter construction requested the colored pigment, Code No. 1562, by Conrad Sovig, San Francisco, California, be used in a ratio of two pounds per sack of concrete. In 1965, Kimberly Construction Company, Inc. of Kimberly, Idaho received the contract for bituminous surfacing of the entire West Entrance Road. The same contract also provided surfacing for a section of the Grand Loop, from Madison Junction toward Old Faithful. [20]

The contractor, who began work on May 23, 1966, obtained the aggregate from the north face of a pit, located 1,000 feet left of station 414 on the West Entrance Road; the porous backfill came from a Forest Service pit about 4 miles north of West Yellowstone, Montana. Husky Oil Company of Cody, Wyoming, supplied the asphalt materials. The crews lived a government trailer house and a rented five room house owned by the Yellowstone Park Company. [21]

The project, which was completed in October, 1966, involved widening the existing asphalt treated base to afford a uniform 22 feet surface with 4 feet stabilized shoulders. In areas of severe distress, the existing stabilized base was removed. Some of these areas required the removal of the untreated base and subbase. The engineers found that these problem areas contained excessive amounts of plastic fines in the subgrade. Paving and a chip seal were placed on the parking areas along the road. The shoulders were given a Type 3 seal coat. [22]

The only major structure on the road is the Madison River Bridge, built in 1958. The three span continuous steel girder with concrete deck is 203 feet long. The deck width from curb to curb is 28 feet 4 inches. The bridge roadway is flanked by a 2-feet wide concrete sidewalk on one side and a 3-feet concrete sidewalk on the other. The bridge has steel rails. [23]

|

|

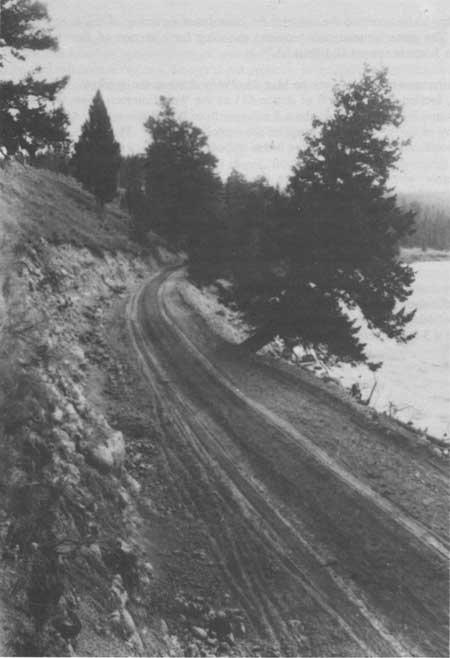

Road along Madison River, ca. 1900 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

Road at Madison Junction, 1905 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

West Entrance Station, 1924 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

|

|

West Entrance Station, 1992 Courtesy Yellowstone National Park Archives |

CHAPTER XVII:

ENDNOTES

1. Robert R. O'Brien, "The Yellowstone National Park Road System: Past, Present, and Future," (Ph.D. Diss., University of Washington, 1964).

2. O'Brien, "The Yellowstone National Road System: Past, Present, and Future." The quotation is from Frank Carpenter's Adventures in Geyser Land, reprinted Frank Carpenter, The Wonders of Geyser Land, ed. H.D. Guie and L. F. McWhorter (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1935).

3. Philetus Norris, Annual Report of the Superintendent of the Yellowstone National Park for the Year 1880 (Washington D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1881), 4, 9.

4. Norris, Annual Report of the Superintendent of the Yellowstone National Park for the Year 1880, 5, 9-10. The new west entrance route left the Madison River at Riverside, proceeded over the Madison Plateau, joining the Firehole River near Nez Perce Creek. The Old Fountain Trail follows the route quite closely.

5. P. H. Conger, Annual Report of the Superintendent of the Yellowstone National Park to the Secretary of the Interior by P. H. Conger, Superintendent, for the Year 1882 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1882), 4.

6. O'Brien, "The Yellowstone National Park Road System: Past, Present, and Future," 116.

7. George S. Anderson, Report of the Officer in Charge of the Construction and Maintenance of Roads in the Yellowstone National Park to the Secretary of War, 1896 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1896), 5.

8. Hiram Chittenden, Annual Report Upon the Construction, Repairs, and Maintenance of Roads and Bridges in the Yellowstone National Park in the Charge of Hiram A. Chittenden, Captain, Corps of Engineers, Appendixes GGG and KKK of the Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers for 1905 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1905), 2820. Ernest Peek, Annual Report of the Chief of Engineers for 1909 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908), 2548.

9. James Parker, Acting Assistant Secretary of the Interior to Lt. Col. L. Brett, Acting Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, 16 May 1914. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

10. "First Endorsement from t/.he Major, Army Corps of Engineers, October 19, 1914." The park was opened to automobile traffic in August, 1915.

11. Annual Report of the Superintendent of National Parks to the Secretary of the Interior For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1916 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1916), 33.

12. Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1924, and the Travel Season, 1924 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1924), 34. Several routes led to the West Entrance of the Park.

There are several roads leading to the west entrance, most important of which is the so-called Warm River Yellowstone road, referred to in Director McDonald's letter of Sept. 7, 1923 to you. This is the road that Mather and Engineer Burney wanted to travel in late July but were prevented by so doing by graveling operations. I had this road inspected Oct. 16th and 17th by the Engineer of the Park and Assistant Superintendent and I quote the following from the Engineer's report:

Inspection of this road was made during a snow storm, and again on the following day when the snow was melting. From West Yellowstone to the foot of the grade leading over Targhee Pass, we found the road partly graded but not graveled. Water was standing everywhere from the melting snow and mudholes were numerous. The next five miles over the pass is newly graded and partly graveled and in good condition. The next five miles across the flat south of Henrys Lake is a good grade and well drained but not graveled and was so slick we had difficulty in staying on the grade. From the lower end of Henrys Lake flat to the top of the grade south of Warm River, a distance of about 35 miles, is an excellent road, with good grades, well drained and graveled. The remaining six miles to Ashton we found very slick. A little gravel on this section would make it an excellent road. Closely associated with this road is the road to the Bechler River, or southwest corner of the park, which I will refer to later in this report. Another road leads to West Yellowstone from the Ruby Valley through the old mining communities of Alder Gulch and Virginia City. This road is usually known as the Vigilante Trail. It is generally in good condition but considerable improvement can be made in the highway by widening it and surfacing it in places where the material of the road becomes slippery in wet weather. Another road leads up the Madison River to West Yellowstone from Three Forks, Montana. This road is usually in very good condition and I have heard no adverse comments on it during the past summer although like most of the other mountain roads in this state it can be improved by widening and surfacing.

Horace Albright, Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park to Stephen Mather, 22 October 1923. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

13. Guy Edwards, Assistant Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, to Horace Albright, Director of the National Park Service, 10 November 1932. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

14. A. Stinson, "Location Survey Report (1934) on The Madison Junction - West Yellowstone Entrance Highway, The West Entrance Road, Route No. 3, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, May 11, 1936."

18. "Maintenance Plans and Estimates, Yellowstone National Park, January 1 to December 31,1946."

19. Warren Hamilton, Acting Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, to Regional Director, Region Two, National Park Service, 18 February 1955. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

20. "Final Construction Report (1966) on Yellowstone National Park Project 1-C(1) and 3(1) Bituminous Surfacing Grand Loop and West Entrance, Yellowstone National Park, State of Wyoming." Luis Gastellum, Acting Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, to Steve Lucas, Project Engineer, Bureau of Public Roads, 19 October 1960. Yellowstone National Park Archives, Yellowstone National Park.

23. "Parkwide Road Engineering Study of the Yellowstone National Park Road System, Draft Report, October 1986," U. S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Vancouver, Washington, 1986. Volume 1.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs-roads/chap17.htm

Last Updated: 20-Apr-2016