|

National Park Service

Confinement and Ethnicity An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites |

|

Chapter 17

Department of Justice and U.S. Army Facilities

Most Japanese Americans interned during World War II were held in facilities run by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) and Wartime Civilian Control Agency (WCCA) described in previous chapters. However, other facilities were also used to imprison Japanese Americans during the war. In all, over 7,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese from Latin America were held in internment camps run by the Department of Justice and the U.S. Army. Eight of these facilities were visited for this project.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor and prior to Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, about 4,000 individuals from all over the U.S. were detained by the FBI. Over half of these were Japanese immigrants who were long-term U.S. residents denied U.S. citizenship by discriminatory laws. These Issei, now classified as "enemy aliens," were first sent to temporary detention stations, then transferred to locations known generally as "Justice Department Camps." The camps were run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, part of the Department of Justice. After hearings, most of the Issei were then sent to U.S. Army internment camps where they remained through May 1943. After that time the internees were returned to Department of Justice control for the duration of the war.

Published literature provides few details about the Japanese American experiences at these facilities. Weglyn (1976:176) notes that most of the U.S. Army and Department of Justice internment camps were considered temporary, and even a complete listing of the camps and internees is not available. Weglyn collected information on the distribution of relief goods sent by the Japanese government through the Red Cross to estimate relative numbers of persons of Japanese ancestry held at various locations. However, as Weglyn notes, these camps often included not only Japanese American Issei who were long-term residents of the United States, but also persons of Japanese ancestry from Latin America.

Temporary Detention Stations

Figure 17.1. Air view of Ellis Island, 1993. (California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside) |

The Issei who were apprehended by the FBI as soon as the U.S. entered the war were first held at various "temporary" locations prior to being sent to more permanent facilities. The temporary detention stations were located at Angel Island, San Pedro, Sharp Park, and Tuna Canyon in California, and Ellis Island, New York, East Boston, Massachusetts, Cincinnati, Ohio, and Seattle, Washington (Weglyn 1976). The two most prominent locations were the immigration stations at Ellis Island and Angel Island.

Ellis Island, a mostly artificial island of about 27 acres in Upper New York Bay, has been government property since 1808. Between 1892 and 1941 it served as the chief entry station for immigrants to the United States. During World War II it was used as a detention center to hold enemy aliens awaiting hearings. In December 1941 Ellis Island held 279 Japanese, 248 Germans, and 81 Italians, all removed from the East Coast (Figure 17.1). Thereafter several hundred detainees, mostly German and Italian nationals, were brought to Ellis Island each month. Most were transferred or released within 1 to 4 months, however some were held for up to 2 years. In February 1944 there were only three Japanese Americans still being held there and in June 1944 only one Japanese American (Jacobs 1997). The immigration center is now run as a museum by the National Park Service.

Figure 17.2. Detainee barracks at the Angel Island Immigration Station. (Angel Island Foundation) |

The Angel Island immigration station is known as the "Ellis Island of the West." The 740-acre island is in the western part of San Francisco Bay. The immigration station, on the north side of the island, was opened in 1910 to handle an expected flood of European immigrants after the opening of the Panama Canal (Figure 17.2). Instead, the vast majority of immigrants were from Asia, including 175,000 Chinese and 100,000 Japanese. The immigration station was closed in 1940 after the administration building burned down. The property was then turned over to the U.S. Army, which used it as a POW processing center. For a short time one of the barracks at the facility was used to house enemy aliens. Buildings remaining at the site today include a detention barracks, two military barracks, a guard tower, a hospital building, and the power plant. Today a museum is located in the detention barracks. It includes a re-creation of one of the dormitories featuring some of the many poems carved into the walls by Chinese immigrants. The second floor of the barracks has several inscriptions written by Japanese and German POWs (Quan 1999).

Department of Justice Internment Camps

Eight internment camps run by the Department of Justice held Japanese Americans. Three of these were in Texas, two were in New Mexico, and one each was in Idaho, Montana, and North Dakota. Most of these facilities held only men, but Segoville in Texas housed single women and families, and Crystal City, also in Texas, held families. Kooskia, in Idaho, was a highway construction camp. All of these facilities were guarded by Border Patrol agents, rather than military police as at the relocation and assembly centers.

Department of Justice Internment Camps

Crystal City, Texas

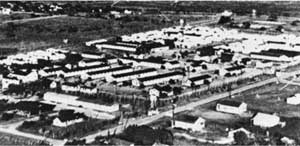

The Crystal City facility, located next to a town of the same name, was originally a Farm Security Administration migratory labor camp for 2,000 people. When it was converted to an internment camp, Crystal City was expanded to house 3,500 people, and a fence and guard towers were added (Figure 17.3). Internee facilities included apartments with shared bathrooms, three-room cottages, and one-room shelters, all within a 290-acre area (Walls 1987; Figure 17.4).

Figure 17.3. Crystal City Internment Camp. (National Archives photograph) |

Figure 17.4. Housing at Crystal City. (National Archives photograph) |

Although the internment camp was originally intended only for persons of Japanese ancestry and nationality, 35 German aliens and their families were the first to arrive, in December 1942. The German imprisonment (and that of one Italian family) at Crystal City was to be temporary while other facilities were being prepared for them. These first internees helped in the construction at the Crystal City camp. The first Japanese U.S. resident aliens arrived at Crystal City in March 1943. Rather than relocate the Germans the camp was divided into separate sections for each ethnic group.

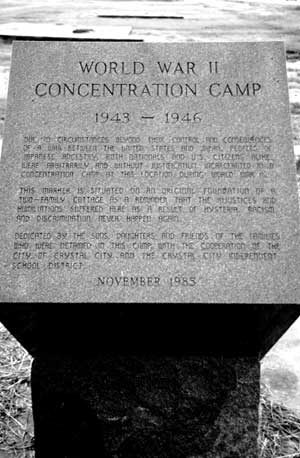

Figure 17.7. Monument at the site of the Crystal City Internment Camp. |

The peak population of the Crystal City camp was around 4,000, of whom two-thirds were of Japanese ancestry. About 600 of these were from Hawaii and 660 from Peru. Because of the unwilling presence of the Japanese Peruvians, the camp was not closed until late 1947. The Peruvian government did not want the Japanese Peruvians returned, most did not want to go to Japan, and the U.S. government who brought the Japanese Peruvians to the U.S. claimed they were illegal immigrants who could not be released. Eventually the Japanese Peruvians left for jobs at Seabrook Farms in New Jersey, as many Japanese Americans had done previously.

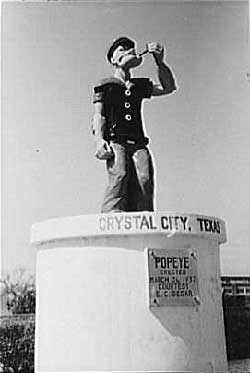

Today the town of Crystal City has grown around the internment camp site, which is now owned by the school district. A local landmark present during the internment still stands, though it has been moved from the town park to the town hall (Figures 17.5 and 17.6). This statue of the cartoon character Popeye was erected in 1932 as a symbol of the self-proclaimed "Spinach Capital of the World."

At the internment camp site there are three schools, athletic fields, a small airport, city social services buildings, and a recently built low-income housing project on the site. A monument commemorating the internment, a large engraved granite block (Figures 17.7 and 17.8), is located on a former cottage foundation. There are five other cottage foundations in the immediate area (Figure 17.9). Other possible camp remains at the site include a few scattered foundations (Figure 17.10), a well (Figure 17.11), and some road alignments.

An elementary school building is in the same location and in the same configuration as the former German internee elementary school (Figure 17.12). One of the more interesting features remaining is that of the camp's large concrete swimming pool, now filled in with dirt and overgrown with vegetation (Figures 17.13 and 17.14). Access to the eastern portion (rear) of the camp site is restricted by the airport and private land. This area would have likely had the hog farm, landfill, and sewage disposal facilities, as well as a picnic area known to be on the nearby Nueces River.

Figure 17.5. Popeye monument in 1939. (Russell Lee photograph, Library of Congress) |

Figure 17.6. Popeye monument today. |

Figure 17.8. Overview of monument and slab foundations at the Crystal City Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.9. Foundation of three-room cottage at the Crystal City Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.10. Concrete slab at the site of the Crystal City Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.11. Well and concrete slab at the site of the Crystal City Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.12. Elementary school at the former location of the Crystal City Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.13. Swimming pool at the Crystal City Internment Camp. (National Archives) |

Figure 17.14. Remains of the concrete swimming pool at the Crystal City Internment Camp today (shallow "wading pool" end). |

|

Department of Justice Internment Camps

Kenedy, Texas

Figure 17.15. Kenedy Alien Internment Camp. (from Walls 1987) |

The Kenedy Internment Camp originally was a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp. The adjacent town of Kenedy made a vigorous lobbying effort to bring the internment camp to Kenedy after the CCC camp was disbanded. For the internment camp, over 200 additional buildings, watchtowers, and a 10-foot-high fence were constructed on the 22-acre site (Figure 17.15). Administrative offices were across a road from the camp proper. A 32-acre vegetable farm nearby was worked by Japanese internees. German internees ran a slaughterhouse.

The first internees arrived in April 1942. These prisoners, 464 Germans, 156 Japanese, and 14 Italians, had been living in Latin America. The U.S. Government had convinced the countries of Latin America to send these people, who had retained their original citizenship, to the U.S. so they could be exchanged for Allied prisoners held by Japan. By 1943 there were about 2,000 internees at the camp. The 705 of Japanese ancestry included some long-term residents of the U.S. The internees were transferred to other facilities and the Kenedy facility was used to house German POWs in September 1944. After July 1945, Kenedy housed several hundred Japanese POWs, including the first Japanese prisoner captured in the war (from a midget submarine at Pearl Harbor).

Figure 17.16. Residential neighborhood at the site of the Kenedy Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.17. Concrete pillars at the site of the Kenedy Internment Camp. |

The internment camp is mentioned on the town of Kenedy's historical marker, located downtown. The Kenedy Chamber of Commerce provides directions to the site, which is now a residential area (Figure 17.16). The local library has "POW camp" file which consists mostly of newsletters in German by a POW group and local newspaper articles about the camp. They also have a report by a local high school student on the town's history that includes information on the camp. The report indicates that not much remains of the camp except a fountain built by the Japanese civilian internees, now in a residential backyard (Garcia 1991). Next door to the property with the fountain there is some concrete rubble used for a retaining wall that may have been recycled from camp building foundations. Along the main road on the south side of the current residential area there are two short concrete pillars which are also probably from the camp (Figure 17.17). Located on either side of a road on two different properties, they likely marked the south entrance to the camp administrative area.

Department of Justice Internment Camps

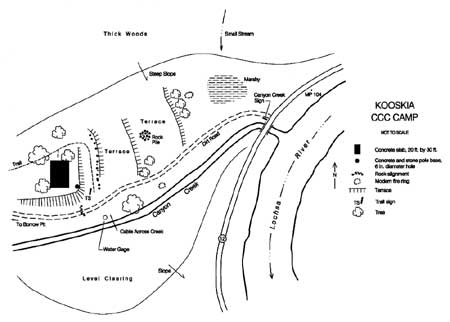

Kooskia, Idaho

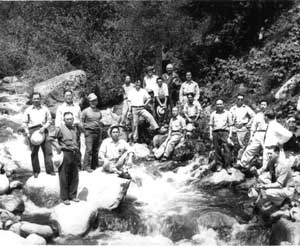

Figure 17.18. Caucasian staff and Japanese American internees take a break at the Kooskia Work Camp. (from Wegars 1999b) |

The Kooskia facility was a highway construction camp in a remote area of north-central Idaho near the small hamlet of Lowell, 40 miles east of the town of Kooskia. The work camp was located at an old Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp on the Clearwater National Forest. Although some of the internees held camp jobs, most of the all-male, paid internee crew were construction workers for the present U.S. Highway 12 (Lewis and Clark Highway) along the Lochsa River, between Lewiston, Idaho, and Lolo, Montana. A total of 256 Japanese aliens, 24 male and three female Caucasian civilian employees, and one Japanese American interpreter lived at the Kooskia camp between May 1943 and May 1945 (Figure 17.18). The internees were from Alaska, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Texas, Utah, and Washington, and included at least 28 from Peru, two from Mexico, and two from Panama (Gardner 1981; Minidoka Irrigator 5/1/43; Wegars 1999a, 1999b).

Figure 17.19. Site of the Kooskia Work Camp today. |

Figure 17.20. Concrete slab at the site of the Kooskia Work Camp. |

The site of the Kooskia Work Camp is still within the Clearwater National Forest, near milepost 104 of U.S. Highway 12 and about 3 mile west of Apgar campground on the north side of Canyon Creek. Very little evidence remains of the former camp (Figure 17.19). There is a 20 foot by 30 foot concrete slab, a few rock features, and several leveled earthen terraces (Figures 17.20 and 17.21). However, the area is heavily wooded and lush, so vegetation may hide additional features. In addition, some of the rocks in recent campfire rings may have been "recycled" from camp features.

Figure 17.21. Sketch map of the Kooskia Work Camp. (click image for larger size (~64K) ) |

Department of Justice Internment Camps

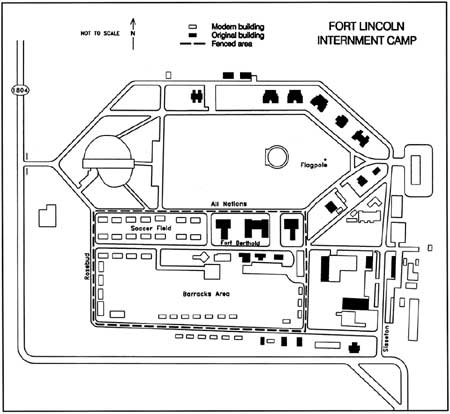

Fort Lincoln, North Dakota

Figure 17.22. Fort Lincoln Internment Camp. (from Fox 1996) |

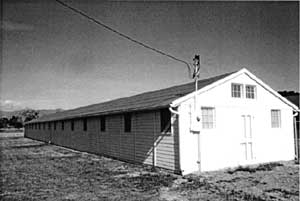

Known today as the United Tribes Technical College, the one-time Fort Lincoln Internment Camp lies five miles south of Bismarck, North Dakota. The brick buildings which are presently used by the college were built in 1903 by the army as a military base. In the 1930s Fort Lincoln became the state headquarters of the CCC, which put up numerous prefabricated wooden buildings at the fort. During World War II, the CCC barracks buildings and two brick army barracks were fenced and used to house internees (Bismarck Tribune 8/4/41; Vyzralek n.d.; Figures 17.22 and 17.23).

The first internees held at Fort Lincoln were Italian and German seamen who had been on Italian and German commercial ships in U.S. waters in 1939 when the war started in Europe. Eight-hundred Italians arrived in April, but soon left for Fort Missoula, Montana. Shortly after the first Japanese American Issei arrived in 1942, they were transferred to other camps, leaving the Germans the sole internees there until February 1945. At that time 650 Japanese Americans were brought in, about half of them so-called "recalcitrants" from camps at Tule Lake, California, and Santa Fe, New Mexico. These internees had renounced their American citizenship and were to be sent to Japan after the war. The rest of the new arrivals were Japanese nationals to be repatriated after the war (Fox 1996).

Within the camp the Japanese and German barracks were separated, but the internees were allowed to mingle. Use of the camp laundry was alternated, and each group had separate areas of the mess hall and kitchen, divided initially by a partition, and then only by a line on the floor. The camp hospital had fifty beds, and was staffed by two part-time Public Health Service doctors and two nurses. In addition, both the Japanese and Germans maintained their own infirmaries and dispensaries with internee doctors (Fox 1996).

Figure 17.23. Guard tower at the Fort Lincoln Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.24. Army barracks at Fort Lincoln today. |

After the war, Fort Lincoln was designated the headquarters for the Garrison Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, serving as the planning center for the Garrison Dam Project. The Fort was declared surplus by the U.S. Army in 1966, remodeled, and used as a Job Corps Training Center in 1968. When the Corps closed, United Tribes obtained the use of the property as its campus.

Figure 17.25. Fort Lincoln Internment Camp. (click image for larger size (~85K) ) |

Today most of the old brick army buildings are still present, including the barracks used to house internees (Figure 17.23 and 17.24). However, all of the wooden CCC buildings have been removed and there is now married-student housing in the former soccer field and CCC barracks area (Figure 17.25). A stone entry gateway is at the college entrance along State Highway 1804, one-quarter mile south of the Bismarck Airport (Figures 17.26 and 17.27). Articles in the local newspaper indicate that some former internees have returned to visit the site (Bismarck Tribune September 27, 1979 and August 2, 1996). There is no marker or memorial at the site.

Figure 17.26. North half of stone entry gate at Fort Lincoln. |

Figure 17.27. South half of stone entry gate at Fort Lincoln. |

Department of Justice Internment Camps

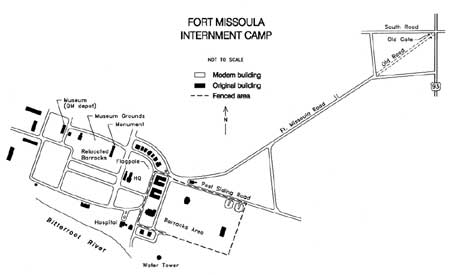

Fort Missoula, Montana

Figure 17.37. Relocated CCC barracks (future exhibit building) on Fort Missoula Museum grounds. |

Fort Missoula is an old U.S. Army post located just outside the town of Missoula, Montana. The fort was used as a regional headquarters for the CCC in the 1930s and was turned over to the Department of Justice in 1941. Two Mission-style Army barracks and most of the CCC camp facilities were fenced for use as internee housing, and guard towers were added (Benedetti 1997; Long 1991; Van Valkenburg 1995; Figures 17.28-17.30).

The first internees at the camp were 25 Japanese American Issei from Salt Lake City who arrived on December 18, 1941. By the end of 1941 there were 633 Issei held at the fort. By April 1942 there were 2,003 men, roughly half Japanese Americans and half Italian nationals. The average age of the Japanese Americans was 60 (Van Valkenburg 1995). Several internees died soon after their arrival, one even on his first day at Fort Missoula (Glynn 1994). All of the Issei internees were given cursory hearings and most were then transferred to other internment camps or relocation centers. During their stay a few volunteered for work on local farms. By the end of 1942 only 29 Japanese Americans were left at the fort.

After the last Japanese Americans left, the Italian national population rose to over 1,200. Like the Japanese Americans, the Italians worked on local farms, but also fought forest fires and worked in Missoula until they were released following Italy's surrender in 1943. In March 1944, 258 Japanese from Hawaii were temporarily held at Fort Missoula before being transferred to Santa Fe, New Mexico (Figure 17.33). In July 1944 the facility was officially closed.

Figure 17.36. Fort Missoula Internment Camp. (click image for larger size (~48K) ) |

Figure 17.38. Guard tower at Fort Missoula. (from Fox 1996) |

Today the 32-acre fort is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. There are still several officers' homes along a tree-lined street and other structures at their original locations (Figure 17.32). Along U.S. Highway 93, about one mile east, the original stone entry posts remain, although the fort access road has been relocated. Within the original fenced internment area, the two large army barracks are now used by the Forest Service and the U.S. Army Reserve (Figure 17.33).

In a vacant field east of the former army barracks there are several foundations from other army buildings, manholes, and a fire hydrant, but no remnants of the CCC barracks once present (Figures 17.34-17.36). Most of the CCC barracks were torn down in the 1950s or relocated. Several were moved to the Montana State Fair in 1954 and are still in use (Van Valkenburg 1995). One has been returned to the fort museum grounds and will be used for exhibits about the internment (Historical Museum at Fort Missoula 1999; Figure 17.37). Next to the relocated barracks is a guard tower cabin and a monument dedicated to those interned without trial at the site (Figures 17.38-17.40). Both the monument and guard tower cabin were placed as Eagle Scout projects. The fort museum, the old quartermaster depot, currently has an exhibit on the internment and a second guard tower cabin.

Figure 17.28. Fort Missoula Internment Camp. (from Glynn 1994) |

Figure 17.29. CCC barracks at Fort Missoula. (National Archives photograph) |

Figure 17.30. Fenced army barracks at Fort Missoula. (from Fox 1996) |

Figure 17.31. Internees at Fort Missoula. (from Glynn 1994) |

Figure 17.32. Abandoned buildings at Fort Missoula. |

Figure 17.33. Former army barracks at Fort Missoula. |

Figure 17.34. Slab foundation at Fort Missoula. |

Figure 17.35. Concrete post supports and slab at Fort Missoula. |

Figure 17.39. Guard tower cabin at Fort Missoula today. |

Figure 17.40. Internment monument at Fort Missoula. |

Department of Justice Internment Camps

Fort Stanton, New Mexico

Established in 1855, Fort Stanton is in an isolated portion of New Mexico, 35 miles north of Ruidoso. In 1899 the fort was transferred to the Merchant Marine for use as a tuberculosis sanatorium. During World War II the fort was used as an internment camp, mostly for German nationals. In 1953 the fort was transferred to the State of New Mexico, which until recently used it as a minimum security women's prison.

The first internees held at the fort were the German crew of the German luxury liner Columbus which was scuttled off the coast of so Cuba in 1939. Since the U.S. was not at war with Germany at the time the internees were considered "distressed seaman paroled from the German Embassy." They were housed in a deserted CCC barracks across from Fort Stanton, and cultivated a 60-acre farm. When the U.S. entered the war the Department of Justice brought in border patrol agents as guards and the barracks was surrounded with a barbed-wire fence (Banks 1998).

The Department of Justice also established a small disciplinary camp at Fort Stanton for "incorrigible agitators" which they named "Japanese Segregation Camp #1." The camp served the same function, but for non-citizens, as the citizen isolation centers at Moab and Leupp run by the WRA. By late October 1945 there were 58 Japanese Americans incarcerated there (Culley 1991). The exact location of the segregation camp and whether there are any remains left is not known.

Department of Justice Internment Camps

Santa Fe, New Mexico

In February 1942 the Department of Justice acquired an 80-acre site from the New Mexico State Penitentiary that included a CCC camp built in 1933 to house 450 men. By March the CCC camp was expanded to house 1,400 men. Housing included wood and tarpaper barracks and 100 "Victory Huts." All but 14 of the victory huts were later replaced by standard Army barracks (Culley 1991).

The camp originally held 826 Japanese American Issei, all men from California. One died at the camp, 523 were transferred to relocation centers, and 302 were transferred to U.S. Army custody. The last internee left the Santa Fe Internment Camp on September 24, 1942. The camp was then used to house German and Italian nationals until February 1943 when the U.S. Army transferred all civilian internees back to the Department of Justice. The Santa Fe camp was then expanded and by June 1945 it held 2,100 Japanese American men whose average age was 53.

Many of the new arrivals were from the Tule Lake Segregation Center and had renounced their U.S. citizenship. This included 366 of what the government considered the most active pro-Japan leaders at Tule Lake. In March 1945 a riot at Santa Fe began when the "Tuleans" were requested to turn in their sweat shirts with rising sun motifs. After the leaders of the protest were removed to Fort Stanton, a crowd gathered, rocks were thrown, and tear gas and clubs were used to break up the crowd. Over 350 internees were put in a stockade and 17 more were sent to the Fort Stanton segregation camp. There were no further disturbances at the camp even after another 399 internees from Tule Lake arrived.

After the end of the war the Santa Fe facility was used as a holding and processing center for other internment camps. As late as March 1946, 200 Japanese American men were transferred to Santa Fe from Fort Lincoln. However, by May only 12 of these remained. The camp closed shortly thereafter and all property was sold as surplus (Thomas et al. 1994). Today the camp site is within a residential subdivision. At the Rosario Cemetery, -1/2 mile east of the camp site, there are graves from two Japanese American men who died during the internment (Narvot 1999a). A State History Museum committee has proposed placing a plaque paid for with private funds at Frank Ortiz City Park overlooking the site, but as of 1999 local opposition has delayed the plaque's installation (Narvot 1999b).

Department of Justice Internment Camps

Seagoville, Texas

Figure 17.41. Segoville Internment Camp. (from Walls 1987) |

Located outside of Dallas, the Seagoville facility was originally built as a federal prison for women (Figure 17.41). In 1942 it was converted into an internment camp to house 50 female Japanese American language teachers removed from the West Coast. The two-story brown brick buildings at the prison included six dormitories with 40 to 68 rooms each, an auditorium, a school, a vocational arts center, and a hospital. At first there was no fence at the camp, but later a high fence and 50 small plywood huts for family quarters were added to accommodate Japanese families brought from Latin American countries (Walls 1987). Today the facility is a low-security prison for about 850 men. The buildings retain much of the look and feel of the World War II installation.

U.S. Army Facilities

At least 14 U.S. Army facilities held Japanese Americans during World War II. Most were within the coterminous United States, but there were also four small internment camps in Hawaii and a temporary detention camp at a military base in Alaska. Only one of the U.S. Army internment camps, Camp Lordsburg in New Mexico, was built specifically for the internment of Japanese Americans. Another, at Stringtown, Oklahoma, was at a state prison, and the remainder were located on existing military bases.

U.S. Army Facilities

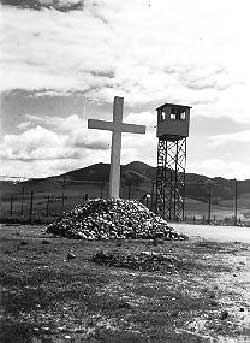

Camp Lordsburg, New Mexico

The Lordsburg Internment Camp is infamous as the location of the shooting under questionable circumstances of two critically ill Japanese American internees by a sentry on July 27, 1942 (Weglyn 1976:312). Construction of the Lordsburg camp began in February 1942. In July, 613 Japanese American Issei men were transferred to Lordsburg from the Fort Lincoln Internment Center in Bismarck, North Dakota. Eventually 1,500 Japanese were interned at the New Mexico camp. By July 1943 all of the Japanese Americans were gone and Italian POWs were brought in; up to 4,000 were held at Lordsburg between 1943 and 1945 (Thomas et al. 1994). The facility was closed by February 1946.

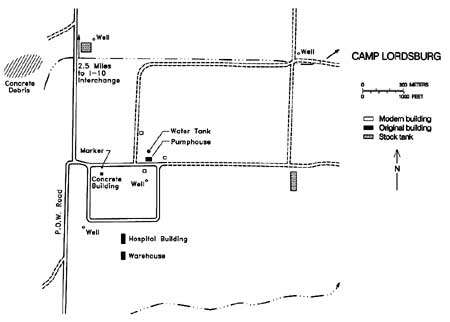

Figure 17.42. Lordsburg Internment Camp. (click image for larger size) |

The internment camp site is located along "P.O.W. Road" about 3 miles east of the town of Lordsburg (Figure 17.42). The area is posted with "no trespassing" signs in both English and Spanish (Figure 17.43). There are three residences on the former camp site (Figure 17.44). The owner of one of the residences confirmed that the private property, which has three owners, was the location of the camp. The owners posted the "no trespassing" sign because people looking for camp remains had frequently wandered around without permission. The camp water tank and an adjacent water treatment building are on one property (Figures 17.45 and 17.46); an adjacent property contains a hospital building (Figure 17.47), now used as a residence and another building now used for storage (Figure 17.48). A small concrete vault-like building and a decorative U.S. seal made of pebbles embedded in concrete is on the third property (Figures 17.49 and 17.50). One of the other owners once tried to move the decorative seal to his property but the current owner of the property on which it is located objected.

Figure 17.49. Small concrete building at the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.50. Detail of decorative at the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

Besides the large structures, not much of the camp is left. A mining company purchased the land in the early 1970s and removed all of the foundation slabs to prepare for building a subdivision, which never materialized. Concrete rubble used for retaining walls for loading ramps at a borrow pit about -1/2 mile northwest of the site may have been salvaged from the camp (Figures 17.51 and 17.52). Large upturned concrete blocks at a road intersection -1/2 mile south of the site may have been guard tower foundations. Some former internees and POWs had returned to visit recently, but such visitors were more common years ago (Robert Lowery, personal communication, 1998).

Figure 17.51. Concrete blocks used for retaining wall northwest of the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.52. Concrete debris northwest of the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

U.S. Army Facilities

Camp Lordsburg, New Mexico

Figure 17.43. P.O.W. Road, Lordsburg, New Mexico. |

Figure 17.44. Sign at the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.45. Water tank and water treatment building at the site of the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.46. Detail of the water tank at the site of the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.47. Hospital building at the site of the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

Figure 17.48. Warehouse south of hospital building at the site of the Lordsburg Internment Camp. |

U.S. Army Facilities

Fort Sill, Oklahoma

Figure 17.53. Area 2400, Fort Sill, Oklahoma. (from Walls 1987) |

Near Lawton, Oklahoma, Fort Sill held some 350 Japanese American Issei who had been first interned at Fort Missoula (Van Valkenberg 1995). It was at Fort Sill that a Japanese Hawaiian internee, distraught over leaving his wife and 12 children behind, was shot and killed by guard while trying to escape. He was crying "I want to go home, I want to go home" as he climbed the barbed wire fence in broad daylight (Saiki 1982).

The Fort Sill Military Reservation is now the headquarters of the U.S. Army Field Artillery. The old fort area established in 1869 is now a National Historic Landmark. It is not clear where on the expansive military base the Japanese Americans were held, but the current fort archeologist noted that in "Area 2400" southwest of Sheridan and Hunt Roads a German POW camp was located (Spivey, personnel communication, 1999). It seems likely that the POW camp and Japanese American internment camp were one and same, as at other U.S. Army facilities. The area has been cleared for the most part and some new buildings have been constructed in the area (Figure 17.53). It is not known if slab foundations still present at the site date to the internment.

U.S. Army Facilities

Stringtown, Oklahoma

A sub-prison was established on 8,000 acres of land 5 miles north of Stringtown, Oklahoma, in 1933, to relieve the overcrowding at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. The sub-prison utilized tents and temporary buildings to house 350 inmates as they built fences, roads, towers, and barracks for the facility. In July, 1937, the prison was transformed into the Oklahoma State Technical Institute, which emphasized training inmates to be skilled workers as part of the rehabilitation process. During World War II the facility became an internment camp for enemy aliens (primarily Japanese Americans), and later it became a POW camp for German naval prisoners. Near the end of the war the facility became a state venereal disease hospital, but in 1945 it again became a sub-prison for the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. It is currently a medium security facility, the Mack Alford Correctional Center, named for its warden from 1973 to 1986 (Anonymous n.d.).

Figure 17.54. Inmate housing at the Strington Internment Camp today. |

Figure 17.55. Administration building at the Strington Internment Camp today. |

In 1988 the facility suffered a riot in which two of the three original inmate housing units were destroyed. The remaining housing unit is still used (Figure 17.54). Also still used is the administration building (Figure 17.55), chapel, gym, and other auxiliary buildings (Figure 17.56). German writing was discovered on the wall of a kitchen when it was recently torn down. Translated it reads "Why be happy, why be outside .... is our work .... life ... whoever play acts can never reckon with himself ... whoever does not ... If there be a thing more powerful than fate, it is the courage which bears it quietly ... and you are so right. The world is quite pitifully wicked and each man in it an evil doer — you and I are naturally not — you and I don't know it all."

Figure 17.56. Guard tower at the Mack Alford Correction Center (Stringtown). |

U.S. Army Facilities

Alaska and Hawaii

Family members of Alaskan Japanese American Issei already imprisoned were held for a short time at Fort Richardson while enroute to the Puyallup Assembly Center in Washington. Fort Richardson is nine miles north of downtown Anchorage, Alaska.

Figure 17.57. Sand Island Internment Camp. (from Ogaawa and Fox 1991) |

In Hawaii, Sand Island in Honolulu was the major detention camp for the initial housing and processing of the 5,000 Japanese Americans detained under martial law (Figure 17.57). There were also small detention camps such as the Kalaheo stockade on the island of Kauai, and Haiku camp on the island of Maui. About 1,500 of those incarcerated in Hawaii were later transferred to mainland internment camps, but the majority were released. On the island of Oahu, a permanent internment camp ringed with barbed wire and guard towers was built. Named Honouliuli, it held 284 Kibei under armed guard (Saiki 1982). In November 1944 the camp was closed. Sixty-seven of the internees were then sent to the mainland, the others were paroled provided they would sign releases holding the U.S. government blameless for their incarceration (Weglyn 1976).

Other U.S. Army Sites

Figure 17.58. Camp McCoy today. (from Badger Challenge 1999) |

In February 1942, 170 Issei were transferred from the Sand Island Internment Camp in Hawaii to Camp McCoy, a former CCC Camp nine miles west of Tomah, Wisconsin. The internees were soon dispersed to other camps and the facility was converted into a training camp for the 100th Infantry Battalion, the all-Nisei Hawaii National Guard unit removed from Hawaii. Fort McCoy is currently used by the Wisconsin Army National Guard and a state-run "at-risk" residential youth program. Many of the original buildings remain at the site (Figure 17.58). A monument at the site commemorates its use as a training camp.

A segregated military base, Camp Forrest, Tennessee, held Japanese Hawaiians transferred from Camp McCoy. At Camp Forrest five men each were housed in small newly-built huts. Some Japanese Hawaiians and about 40 Issei from Fort Missoula were held at Fort Sam Houston along with 300 Alaskan Eskimos. Barracks were tents, surrounded by a barbed wire enclosure. After nine days the internees were transferred to Camp Lordsburg. Camp Livingston, Louisiana, held over 800 persons of Japanese ancestry (Weglyn 1976). Four hundred of these were from the West Coast, 354 were from Hawaii, and 160 were from Panama and Costa Rica.

The distribution of a small quantity of Japanese relief goods (green tea, soya, and bean mash) destined for Camp Florence, Arizona, and Fort Meade, Maryland, from the exchange ship M.S. Gripsholm in June 1942 and December 1943 indicates there were Japanese nationals being held at both camps (Weglyn 1976). No further information about these two locations was obtained.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

wacc/74/chap17.htm

Last Updated: 20-Feb-2004