Like the majority of cliff-dwellings in the Mesa

Verde National Park, Spruce-tree House stands in a recess protected

above by an overhanging cliff. Its form is crescentic, following that of

the cave and extending approximately north and south.

The author has given the number of rooms and their

dimensions in his report to the Secretary of the Interior (published in

the latter's report for 1907-8) from which he makes the following

quotation:

The total length of Spruce-tree House was found to be

216 feet; its width at the widest part 89 feet. There were counted in

the Spruce-tree House 114 rooms, the majority of which were secular, and

8 ceremonial chambers or kivas. Nordenskiöld numbered 80 of the former

and 7 of the latter, but in this count he apparently did not

differentiate in the former those of the first, second and third

stories. Spruce-tree House was in places 3 stories high; the third-story

rooms had no artificial roof, but the wall of the cave served that

purpose. Several rooms, the walls of which are now two stories high,

formerly had a third story above the second, but their walls have now

fallen, leaving as the only indication of their former union with the

cave lines destitute of smoke on the top of the cavern. Of the 114

rooms, at least 14 were uninhabited, being used as storage and mortuary

chambers. If we eliminate these from the total number of rooms we have

100 enclosures which might have been dwellings. Allowing 4 inhabitants

for each of these 100 rooms would give about 400 persons as an

aboriginal population of Spruce-tree House. But it is probable that this

estimate should be reduced, as not all the 100 rooms were inhabited at

the same time, there being evidence that several of them had occupants

long after others were deserted. Approximately, Spruce-tree House had a

population not far from 350 people, or about 100 more than that of

Walpi, one of the best-known Hopi pueblos.a

In the rear of the houses are two large recesses used

for refuse-heaps or for burial of the dead. From the abundance of guano

and turkey bones it is supposed that turkeys were kept in these places

for ceremonial or other purposes. Here have been found several

desiccated human bodies commonly called mummies.

The ruin is divided by a street into two sections,

the northern and the southern, the former being the more extensive.

Light is prevented from entering the larger of these recesses by rooms

which reach the roof of the cave. In front of these rooms are circular

subterranean rooms called kivas, which are

sunken below the surrounding level places, or plazas, the roofs of

these kivas having been formerly level with the plazas.

aOn the author's plan of Spruce-tree House from a

survey by Mr. S. G. Morley, the third story is indicated by

crosshatching, the second by parallel lines, while the first has no

markings. (Pl. 1.)

The front boundary of these plazas is a walla which

when the excavations were begun was buried under debris of fallen

walls, but which formerly stood several feet above the level of the

plazas.

aSee American Anthropologist, n. s., v. no.

2, 224-288, 1903.

MAJOR ANTIQUITIES

Under this term are included those immovable

prehistoric remains which, taken together, constitute a cliff-dwelling.

The architectural features—walls of rooms and structures connected

with them, as beams, balconies, fireplaces—are embraced in the term

"major antiquities." None of these can be removed from their sites

without harm, so they must be protected in the place where they now

stand.

In a valuable article on the ruins in valley of the

San Juan and its tributaries, Dr. T. Mitchell Pruddenb recognizes in

this region what he designates a "unit type;" that is, a ruin

consisting of a kiva backed by a row of rooms generally situated on its

north side, with lateral extensions east and west, and a burial place on

the opposite, or south, side of the kiva. This form of "unit type," as

he points out, is more apparent in ruins situated in an open country

than in those built in cliffs. The same form may be recognized in

Spruce-tree House, which is composed of several "unit types" arranged

side by side. The simplicity of these "unit types" is somewhat modified,

however, in this as in all cliff-dwellings, by the form of the site. The

author would amend Prudden's definition of the "unit type" as applied to

cliff-houses by adding to the latter's description a bounding wall connecting

the two lateral extensions of the row of rooms, thus forming

the south side of the enclosure of the kiva. For obvious reasons, in

this amended description the burial place is absent, as it does not

occur in the position assigned to it in the original description.

bSee H. R. No. 3703, 58th Cong., 3d sess.,

1905—The Ruined Cliff Dwellings in Ruin and Navajo Canyons, In the

Mesa Verde, Colorado, by Coert Dubois.

PLAZAS AND COURTS

As before stated, the buildings of Spruce-tree House

are divided into a northern and a southern section by a street which

penetrates from plaza G to the rear of the cave. (Pl. 1.) The northern

section is not only the larger, but there is evidence that it is also

the older. It is bounded by some of the best-constructed buildings,

situated along the north side of the street. The rooms of the southern

section are less numerous, although in some respects more

instructive.

There are

practically the same number of plazas as of kivas in

this ruin. With the exception of C and D, each plaza

is occupied by a single kiva, the roof of which constitutes the central

part of the floor of the square enclosure (plaza). The plazas commonly

contain remnants of small shrines, fireplaces, and corn-grinding bins,

and are perforated by mysterious holes evidently used in ceremonies.

Their floors are hardened by the tramping of the many feet that passed

over them. The best preserved of all the plazas is that which contains

kiva G. It can hardly be supposed that the roof of kiva A served as a

dance place, which is the ordinary office of a plaza, but it may have

been used in ceremonies. The largest plaza of the series, in the rear of

which are rooms while the front is inclosed by the bounding wall, is

that containing kivas C and D. The appearance of this plaza before and

after clearing out and repairing is shown in plate 3; the view was taken

from the north end of the ruin.

From the number of fireplaces and similar evidences

it may be concluded that the street already mentioned as dividing the

village into two sections served many purposes. Most important of these

was its use as the open-air dwellings of the villagers. Its hardened

clay floor suggests the constant passage of many feet. Its surface

slopes gradually downward from the back of the cave, ending at a step

near the round room in the rear of kiva G. This step marks also the

eastern boundary of the plaza (G) which contains the best-preserved of

all the ceremonial rooms of Spruce-tree House.

The discovery by excavation of the wall that

originally formed the front of the village was important. In this way

was revealed a correct ground plan of the ruin (pl. 1) which had never

before been traced by archeologists. When the work began, this wall was

deeply buried under accumulated debris, its course not being visible to

any considerable extent. By removing the fallen stones composing the

debris the wall could be readily traced. In the repair work the original

stones were replaced in the structure. As in the first instance this

wall was probably about as high as the head, it may have been used for

protection. The only openings are small rectangular orifices, the

presence of one opposite the external opening of the air flue of each

kiva suggesting that formerly these flues opened outside the wall. Two

kivas, B and F, are situated west of this wall and therefore outside the

village. There are evidences of a walk on top of the talus along the

front of the pueblo outside the front wall, and of a retaining wall to

prevent the edge of the talus from wearing away. (Pls. 4, 5.)

CONSTRUCTION OF WALLS

The walls of Spruce-tree House were built of stones

generally laid in mortar but sometimes piled on one another, the joints

being pointed later. Sections of walls in which no mortar was used occur

on the tops of other walls. These dry walls served among other purposes to

shield the roofs of adjacent buildings from snow and rain. Whenever

mortar was used it appears that a larger quantity was employed than was

necessary, the effect being to weaken the wall since the pointing

washed out quickly, being less capable than stone of resisting

erosion. When the mortar wore away, the wall was left in danger of falling

of its own weight. The pointing was generally done with the hands, the

superficial impressions of which show in several places. Small flakes of

stone or fragments of pottery were sometimes inserted in the joints,

serving both as a decoration, and as a protection by preventing the

rapid wearing away of the mortar. Little pellets of clay were also used

in the joints for the same purpose.

The character of masonry in different rooms varies considerably, in some

places showing good, in others poor, workmanship. As a rule the

construction of the corners is weak, the stones forming them being

rarely bonded or tied. Component stones of the walls seldom break

joints; thus a well-known device by means of which walls are

strengthened is lacking, and consequently cracks are numerous and the

work is unstable. Fully half the stones used in construction were

hammered or dressed into desirable shapes, the remainder being laid as

they were gathered, with their flat surfaces exposed when possible.

(Pls. 6, 7.)

Some of the walls were out of plumb when constructed and the faces of

many were never straight. The walls show evidences of having been

repeatedly repaired, as indicated by a difference in color of the mortar

used.

Plasters of different colors, as red, white, yellow, and brown, were

used. The lower half of the wall of a room was generally painted

brownish red, the upper half often white. There are evidences of several

coats of plastering, especially on the walls of the kivas, some of which

are much discolored with smoke.

The replastering of the walls of Hopi kivas is an incident of the

Powamu festival, or ceremonial purification of the fields

commonly called the "Bean planting," which occurs every February. On a

certain day of this festival girls thoroughly replaster the four walls

of the kivas and at the close of the work leave impressions of their

hands in white mud on the kiva beams.

The rooms of Spruce-tree House may be considered under two headings:

secular rooms, and ceremonial rooms, or kivas. The former are

rectangular, the latter circular, in form.

SECULAR ROOMS

The secular rooms are the more numerous in Spruce-tree House. In order

to designate them in future descriptions they were numbered from 1 to

71, in black paint, in conspicuous places on the walls,

(Pl. 1.) This enumeration begins at the north end

and passes thence to the south end of the ruin, but in one or two

instances this order is not followed. The author has given below a brief

reference to some of the important secular rooms in the series.

The foundations of room 1 were apparently built on a

fallen bowlder, the entrance being reached by means of a series of stone

steps built into the side hill. The floor of this room is on the level

of the second story of other rooms, being continuous with the top of

kiva A. It is probable that when this kiva was constructed it was found

impossible to make it subterranean on account of the solid rock. A

retaining wall was built outside the kiva and the intervening space was

filled with earth in order to impart to the room a subterranean

character.

Room 2 has three stories, or tiers, of rooms. The

floor of the second story, which is the roof of the first, is well

preserved, the sides of the hatchway, or means of passage from one room

to the one below it, being almost entire. This room possesses a feature

which is unique. The base of its south wall is supported by curved

timbers, whose ends rest on walls, while the middle is supported by a

pillar of masonry. (Pl. 8.) The T-shaped door in this wall faces south.

It is difficult to understand how the aperture could have been of any

use as a doorway unless there was a balcony below it, and no sign of

such structure is now visible. The west wall of rooms 2 and 3 was built

on top of a fallen rock from which it rises precipitously to a

considerable height. The floor of room 4, which lies in front of kiva A,

is on a level with the roof of the kiva, and somewhat higher than the

surface of the neighboring plaza but not higher than the roof of the

first story. As the floors of room 1 and room 4 are on the same level,

it would appear that both were considerably elevated or so constructed

otherwise that the kiva should be subterranean. This endeavor to render

the kiva subterranean by building up around it, when conditions made it

impossible to excavate in the solid rock, is paralleled in some other

Mesa Verde ruins.

The ventilator of kiva A, as will be seen later, does

not open through the front wall, as is usually the case, but on one

side. This is accounted for by the presence of a room on this side of

the kiva. Rooms 2, 3, 4 were constructed after the walls of kiva A were

built, hence several modifications were necessary in the prescribed plan

of building these rooms.

The foundation of the inclosure, 5, conforms on one

side to the outer wall of the village, and on the other to the curvature

of kiva B. As this inclosure does not seem ever to have been roofed, it

is probable that it was not a house. A fireplace at one end indicates

that cooking was formerly done here. It is instructive to note that the

front wall of the ruin begins at this place.

Rooms 6, 7, 8, which lie side by side, closely

resemble one another, having much in common. They were evidently

dwellings, and may have been sleeping-places for families. Rooms 7 and 8

were two stories high, the floor of no. 8 being on a level with the

adjoining plaza. Room 9 is so unusual in its construction that it can

not be regarded as a living room. It was used as a mortuary chamber,

evidences being strong that it was opened from time to time for new

interments. Room 12 also was a ceremonial chamber, and, like the

preceding, will be considered later at greater length. The walls of the

two rooms, 10 and 11, are low, projecting into plaza C, of whose border

they form a part. Near them, or in one corner of the same plaza, is a

bin, the sides of which are formed of stone slabs set on edge. The use

of this bin is problematical.

The front wall of room 15 had been almost wholly

destroyed before the repair work began, and was so unstable that it was

necessary to erect a buttress to support it. This room, which is one

story high, is irregular in shape; its doorways open into rooms 14 and

16. The walls of rooms 16 and 18 extend to the roof of the cave,

shutting out the light on one side from the great refuse-place in the

rear of the cliff-dwellings. The openings through the walls of these

rooms into this darkened area have been much broken by vandals, and the

walls greatly damaged. Room 17, like 16 and 18, is somewhat larger than

most of the apartments in Spruce-tree House.

Theoretically it may be supposed that when

Spruce-tree House was first settled it had one clan occupying a cluster

of rooms, 1-11, and one ceremonial room, kiva A. As the place grew

three other "unit types" centering about kivas C-H were added, and

still later each of these units was enlarged and new kivas were built in

each section. Thus A was enlarged by addition of B; C by addition of D;

E by addition of F; and G was subordinated to H. In this way the rooms

near the kivas grew in numbers. The block of rooms designated 50-53

is not accounted for, however, in this theory.

Rooms numbered 19-22 are instructive. Their

walls are well preserved and form the east side of plaza C. These walls

extend from the level of the plaza to the top of the cavern, and in

places show some of the best masonry in Spruce-tree House. Just in front

of room 19, situated on the left-hand side as one enters the doorway, is

a covered recess, where probably ceremonial bread was baked or otherwise

cooked. This place bears a strong resemblance to recesses found in Hopi

villages, especially as in its floor is set a cooking-pot made of

earthenware. Rooms 19-21 are two stories high; there are fireplaces

in the corners and doorways on the front sides. The upper stories were

approached and entered by balconies. The holes in which formerly rested

the beams that supported these balconies can be clearly seen.

Rooms 21 and 22 are three stories high, the entrances

to the three tiers being seen in the accompanying view (pl. 6). The

beams that once supported the balcony of the third story resemble those

of the first story; they project from the wall that forms the front of

room 29.

The external entrance to room 24 opens directly on

the plaza. Some of the rafters of this room still remain, and near the

rear door is a projecting wall, in the corner of which is a fireplace.

Although room 25 is three stories high, it does not reach to the cave

top. None of the roofs of the rooms one over another are intact, and the

west side of the second and third stories is very much broken. The

plaster of the second-story walls is decorated with mural paintings that

wi]l be considered more fully under Pictographs. It is not evident how

entrance through the doorway of the second story was made unless we

suppose that there was a notched log, or ladder, for that purpose

resting on the ground. In order to strengthen the north wall of room 25

it was braced against the walls of outer rooms by constructing masonry

above the doorway that leads from plaza D to room 26. This tied all

three walls together and imparted corresponding strength to the

whole.

The lower-story walls of room 26 are in fairly good

condition, having needed but little repair. There is a good fireplace

in the floor at the northeast corner. Excavations revealed a passageway

from kiva D into room 26, the opening into the upper room being situated

near its north wall. The west wall of room 26 is curved. The walls of

rooms 27 and 28 are much dilapidated, the portion of the western section

that remains being continuous with the front wall of the pueblo. A small

mural fragment ending blindly arises from the outside of the west wall

of room 27. This is believed to have been part of a small enclosure used

for cooking purposes. Much repairing was necessary in the walls of rooms

27 and 28, since they were situated almost directly in the way of

torrents of water which in time of rains fall over the rim of the

canyon.

The block of rooms numbered 30-44, situated east

of kiva E, have the most substantial masonry and are the best

constructed of any in Spruce-tree House. (Pl. 9.) As room 45 is only a

dark passageway it should be considered more a street than a dwelling.

Rooms 30-36 are one story each in height, rectangular

in shape, roofless, and of about the same dimensions; of these room 35

is perhaps the best preserved, having well-constructed fireplaces in one

corner. Rooms 37, 38, 39 are built deep in the cavern; their walls,

especially those of 38, are very much broken down. There would seem to be

hardly a possibility that these rooms were inhabited, especially after

the construction of the rooms in front of the cave which shut off all

light. But they may easily have served as storage places. Their walls

were constructed of well-dressed stones and afford an

example of good masonry work.

Here and there are indications of other rooms in the

darker parts of the cave. In some instances their walls extended to the

roof of the cave where their former position is indicated by light bands

on the sooty surface.

Rooms 40-47 are among the finest chambers in

Spruce-tree House. Rooms 48 and 49 are very much damaged, the walls

having fallen, leaving only the foundations above the ground level.

Several rooms in this part of the ruin, especially rooms 43 (pl. 9) and

44, still have roofs and floors as well preserved as when they were

built, and although dark, owing to lack of windows, they have fireplaces

in the corners, the smoke escaping apparently through the diminutive

door openings. The thresholds of some of the doorways are too high above

the main court to be entered without ladders or notched poles, but

projecting stones or depressions for the feet, still visible,

apparently assisted the inhabitants, as they do modern visitors, to enter

rooms 41 and 42.

Each of the small block of rooms 50-53 is one story

and without a roof, but possessing well-preserved ground floors. In room

53 there is a depression in the floor at the bottom of which is a small

hole.a

aIn Hopi dwellings the author has often seen a provisional sipapu

used in household ceremonies.

In the preceding pages there have been considered the

rooms of the north section of Spruce-tree House, embracing dwellings,

ceremonial rooms, and other enclosures north of the main court, and the

space in the rear called the refuse-heap—in all, six circular

ceremonial rooms and a large majority of the living and storage rooms.

From all the available facts at the author's disposal it is supposed

that this portion is older than the south section, which contains but

two ceremonial rooms and not more than a third the number of secular

dwellings.b

bThe proportion of kivas to dwellings in any village is not always the

same in prehistoric pueblos, nor is there a fixed ratio in modern

pueblos, it would appear that there is some relation between the number

of kivas and the number of inhabitants, but what that relation is,

numerically, has never been discovered.

The cluster of rooms connected with kivas G and H

shows signs of having been built by a clan which may have joined

Spruce-tree House subsequent to the construction of the north section of

the village. The ceremonial rooms in this section differ in form from

the others. Here occur two round rooms or towers, duplicates of which

have not been found in the north section.

Room 61 in the south section of Spruce-tree House has

a closet made of flat stones set on edge and covered with a perforated

stone slab slightly inclined from the horizontal.

The inclosures at the extreme south end, which follow

a narrow ledge, appear to have been unroofed passages rather than rooms.

On ledges somewhat higher there are small granaries each

with a hole in the side, probably for the storage of corn.

It will be noticed that the terraced form of

buildings, almost universal in modern three-story pueblos and common in

pictures of ruins south of the San Juan, does not exist in Spruce-tree

House. The front of the three tiers of rooms 22, 23, as shown in plate

3, is vertical, not terraced from foundation to top. Whether the walls

of rooms now in ruins were terraced or not can not be determined, for

these have been washed out and have fallen to so great an extent that it

is almost impossible to tell their original form. Rooms 25-28, for

instance, might have been terraced on the front side, but it is more

reasonable to suppose they were not;a from the arrangement of doors it

would seem that there was a lateral entrance on the ground floor rather

than through roofs.

aNordenskiöld on the contrary seems to make the

terraced rooms one of the points of resemblance between the

cliff-dwellings and the great ruins of the Chaco. He writes:

"On comparison of the ruins in Chaco Cañon with the

cliff-dwellings of Mancos, we find several points of resemblance. In

both localities the villages are fortified against attack, in the tract

of Mancos by their site in inaccessible precipices, in Chaco

Cañon by a high outer wall in which no doorways were constructed

to afford entrance to an enemy. Behind this outer wall the rooms

descended in terraces towards the inner court. One side of this court

was protected by a lower semicircular wall. In the details of the

buildings we can find several features common to both. The roofs between

the stories were constructed in the same way. The doorways were built of

about the same dimensions. The rafters were often allowed to project

beyond the outer wall as a foundation for a sort of balcony (Balcony

House, the Pueblo Chettro Kettle). The estufa at Hungo Pavie with its

six quadrangular pillars of stone is exactly similar to a Mesa Verde

estufa (see p. 16). The pottery strewn in fragments everywhere in Chaco

Canon resembles that found on the Mesa Verde. We are thus not without

grounds for assuming that it was the same people, at different stages of

its development, that inhabitated these two regions."—The Cliff

Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, p. 127.

BALCONIES

Balconies attached to the walls of buildings below

rows of doors occurred at several places. On no other hypothesis than

the presence of these structures can be explained the elevated situation

of entrances opening into the rooms immediately above rooms 20, 21, 22.

In fact, there appear to have been two balconies at this place, one

above the other, but all now left of them is the projecting floor-beams,

and a fragment of a floor on the projections at the north end of the

lower one, in front of room 20. These balconies (pl. 3) were apparently

constructed in the same way as the structure that gives the name to the

ruin called Balcony House; they seem to have been used by the

inhabitants as a means of communication between neighboring rooms.

Nordenskiöld writes:b

The second story is furnished along the wall just

mentioned, with a balcony; the joists between the two stories project a

couple of feet, long poles lie across them parallel to the walls, the

poles are covered with a layer of cedar bast, and, finally with dried

clay.

bIbid., p. 87.

FIREPLACES

There are many fireplaces in Spruce-tree House, in

rooms, plazas, and courts. From their number it is evident that most of

the cooking must have been done by the ancients in the courts and

plazas, rather than in the houses. The rooms are so small and so poorly

ventilated that it would not be possible for any one to remain in them

when fires are burning.

The top of the cave in which Spruce-tree House is

built is covered with soot, showing that formerly there were many fires

in the courts and other open places of the village. In almost every

corner of the buildings in which a fire could be made the effect of

smoke on the adjoining walls is discernible, while ashes are found in a

depression in the floor. These fireplaces are very simple, consisting

simply of square box-like structures bounded by a few flat stones set on

edge. In other instances a depression in the floor bordered with a low

ridge of adobe served as a fireplace. There remains nothing to indicate

that the inhabitants were familiar with chimneys or firehoods as is the

case among the modern pueblos. Certain small rooms suggest cook-houses,

or places where piki, or paper bread, was fried by the women on

slabs of stone over a fire, but none of these slabs were found in place.

The fireplaces of the kivas are considered specially in an account of

the structure of those rooms (see p. 18).

No evidence that Spruce-tree House people burnt coal

was observed, although they were familiar with lignite and seams of coal

underlie their messa.

DOORS AND WINDOWS

There are both doors and windows in the secular

houses of Spruce-tree House, although the two rarely exist together. The

windows, most of which are small square peep-holes or round orifices,

look obliquely downward, as if their purpose was rather for outlook than

for air, the latter being admitted as a rule through the doorway. (Pls.

10, 11.)

The two types of doorways differ more in shape than

in any other feature. These types may be called the rectangular and the

T-shaped form. Both are found at a high level, but it can not be

discovered how they could have been entered without ladders or notched

logs. Although these modes of entrance were apparently often used it is

remarkable that no traces of the logs have yet been found in the extensive

excavations at Spruce-tree House. The T-shaped doorways are

often filled in at the lower or narrow part, sometimes with stones

rudely placed, oftentimes with good masonry, by which a T-shaped door is

converted into one of square type. Doorways of both types are often

completely filled in, leaving only their outlines on the sides of the

wall.

FLOORS AND ROOFS

The floors of the rooms are all smoothly plastered

and, although purposely broken through in places by those in search of

specimens, are otherwise in fairly good condition. In one of the rooms

at the left of the main court is a small round hole at the bottom of a

concave depression like a fireplace, the use of which is not known.

Many of the floors sound hollow when struck, but this fact is not an

indication of the presence of cavities below. In tiers of rooms that

rise above the first story the roof of one room forms the floor of the

room above it. Wherever roofs still remain they are found to be

well-constructed (pl. 9) and to resemble those of the old Hopi houses.

In Spruce-tree House the roofs are supported by timbers laid from one

wall to another; these in turn support crossbeams on which were placed

layers of cedar bark covered with a thick coating of mud: In several

roofs hatchways are still to be seen, but in most cases entrances are

at the sides. One second-story room has a fireplace constructed like

those on the ground floor or on the roof. Several fire places were found

on the roofs of buildings one story high.

The largest slabs of stone used in the construction

of the rooms of Spruce-tree House were generally made into lintels and

thresholds. The latter surfaces were often worn smooth by those crawling

through the opening and in some cases they show grooves for the

insertion of the door slabs. Although the sides of the door are often

upright slabs of stone these may be replaced by boards, set in adobe

plaster. Similar split boards often form lintels.

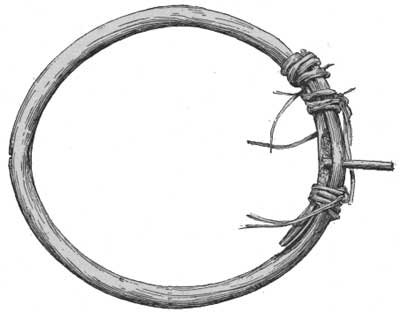

The door was apparently a flat stone set in an adobe

casing on the inside of the frame where it was held in position by a

stick. Each end of this stick was inserted into an eyelet made of bent

osiers firmly set in the wall. Many of these broken eyelets can still be

seen in the doorways and one or two are still entire. A slab of stone

closing one of the doorways is still in place.

KIVAS

There are eight circular subterranean rooms

identified as ceremonial rooms, or kivas, in Spruce-tree House

(pls. 12, 13). Beginning on the north these kivas are designated by

letters A-H. When excavation began small depressions full of

fallen stones, with here and there a stone buttress projecting out of

the debris, were the only indications of the sites of these important

chambers. The walls of kiva H were the most dilapidated and the most

obscured of all, the central portion of the front wall of rooms 62 and

63 having fallen into this chamber; added to the debris were the high

walls of the round room, no. 69. Kiva G is the best-preserved kiva and

kiva A the most exceptional in construction. Kiva B, never seen by

previous investigators, was in poor condition, its walls

being almost completely broken down. Part of the wall of kiva A is

double (pl. 13), indicating a circular room built inside another room

the shape of which inclines to oval, the former utilizing a portion of

the wall of the latter. This kiva is also exceptional in being

surrounded on three sides by rooms, the fourth side being the wall of

the cavern. From several considerations the author regards this as the

oldest kiva in Spruce-tree House.

The typical structure of a Spruce-tree House kiva is

as follows: Its form is circular or oval; the site is subterranean, the

roof being level with the floor of the surrounding plaza. (Pls.

13-15.) Two walls, an outer and an inner, inclose the room, the

latter forming the lower part. Upon the top of this lower wall rest six

pedestals, which support the roof beams; the outer wall braces these

pedestals on one side. The spaces between these pedestals form recesses

in which the floors extend a few feet above the floor of the room.

The floor of the kiva is generally plastered, but in

some cases is solid rock. The fireplace is a circular depression in the

floor, its purpose being indicated by the wood ashes found therein. Its

lining is ordinarily made of clay, which in some instances is replaced

by stones set on edge.

The other important opening in the floor is one

called sipapu, or symbolic opening into the underworld. This is

generally situated near the center of the room, opposite the fireplace.

This opening into the underworld is barely large enough to admit the

human hand and extends only about a foot below the floor surface. It is

commonly single, but in one kiva two of these orifices were detected. A

similar symbolic opening occurs in modern Hopi kivas, as has been repeatedly

described in the author's accounts of pueblo ceremonials. An

important structure of a Spruce-tree House kiva is an upright slab of

rock, or a narrow thin wall of masonry, placed between the fire place

and the wall of the kiva. This object, sometimes called an altar, serves

as a deflector, its function being to distribute the air which enters

the kiva at the floor level through a vertical shaft, or ventilator.

Every kiva has at least one such deflector, a single fire place, and the

sipapu, or ceremonial opening mentioned above.

Several small cubby-holes, or receptacles for paint

or small ceremonial objects, generally occur in the lower walls of the

kiva. In addition to these there exist openings ample in size to admit

the human body, which serve different purposes. The first kind

communicate directly with passageways through which one can pass from the

kiva into a neighboring room or plaza. Such a passageway in kiva E has

steps near the opening in the floor of room 35. This entrance is not

believed, however, to be the only way by which one could enter or leave

this room, but was a private passage, the main entrance being through the roof. Another lateral

passageway is found in kiva D, where there is an opening in the south

wall communicating with the open air by means of an exit in the floor

of room 26; another opening is found in the wall on the east side. Kiva

C has a lateral opening communicating with a vertical passageway which

opens in the middle of the neighboring plaza. In addition to lateral

openings all kivas without exception have others that serve as

ventilators, as before mentioned, by which air is introduced on the

floor level of the kivas. The opening of this kind communicates through

a horizontal passage with a vertical flue which finds its way outside

the room on a level with the roof. In cases where the kiva is situated

near the front wall these ventilators open through this wall by means of

square apertures. All ventilator openings are in the west wall except

that of kiva A, which is the only one that has rooms on that side.

The construction of kiva roofs must have been a

difficult problem (pls. 14, 15). The beams (L-1 to L-4) are

supported by the six pedestals (C) which stand upon the banquettes (A),

and in turn are supported by the outer wall (B) of the kiva. On top of

each of these pedestals is inserted a short stick (H) that served as a

peg on which the inmates hung their ceremonial paraphernalia. The

supports of the roof were cedar logs cut in suitable lengths by stone

axes. Three logs were laid, connecting adjacent pedestals upon which they

rested. These logs, which were large enough to support considerable

weight, had been stripped of their bark. Upon these six beams were laid

an equal number of beams, spanning the intervals between those first

placed, as shown in the illustration (pl. 15). Upon the last-mentioned

beams were still other logs extending across the kiva, as also shown in

the plate.

The main weight of the roof was supported by two

large logs which extended diametrically across the kiva from one wall to

the wall opposite; they were placed a short distance apart, parallel

with each other. The distance between these logs determines the width of

the doorway, two sides of which they form. The other two sides are

formed by two beams (L-4) of moderate size, laid across these logs,

the space between them and the two beams being filled in with other

logs, forming a compact framework. No nails are necessary in a roof

constructed in this way.

The smaller interstices between the logs were filled

in with small sticks and twigs, thus preventing soil from dropping into

the room. Over the supports of the roof was spread a layer of cedar bark

(M) covered with mud (N),laid deep enough to bring the top of the roof

to the level of the plaza in which the kiva is situated.

No kiva was found in which the plastering of the

walls was supported by sticks, as sometimes occurs here, according to

Nordenskiöld and in one or more of the Hopi kivas. The plastering

of the walls was placed directly on the masonry.

It is probable that the kiva walls were painted with

various devices before their roofs fell in and other mutilation of the

walls took place. Among these designs parallel lines in white were

common. Similar lines are still made with meal on kiva walls in Hopi

ceremonies, as the author has often described. One of the pedestals of

kiva A is decorated with a triangular figure on the margin of the dado,

to which reference will be made later.

The author has found no conclusive answer to the

question why the kivas are built underground and are circular in form.

He believes both conditions to be survivals of ancient "pit-houses," or

subterranean dwellings of an antecedent people. In this explanation the

kiva is regarded as the oldest form of building in the cliff-dwellings.

We have the authority of observation bearing on this point.

Pit-dwellings are recorded from several ruins. In a recent work Dr.

Walter Hough figures and describes certain dwellings of subterranean

character that are sometimes found in clusters,a while the present

author has observed subterranean rooms so situated as to leave no doubt

of their great antiquity.b

aBulletin 35 of the Bureau of American Ethnology,

Antiquities of the Upper Gila and Salt River Valleys in Arizona and New

Mexico.

bIn some cases the walls of the later rectangular rooms are

built across and above them, as in compound B in the Casa Grande group

of ruins.

The form of the kiva is characteristic and may be

used as a basis of classification of pueblo culture. The people whose

kivas are circular inhabited villages now ruins in the valley of the

San Juan and its tributaries, in Chelly canyon, Chaco canyon, and on the

western plateau of the Rio Grande.

The rectangular kiva is a structure altogether

different from a round kiva, morphologically, genetically, and

geographically. It is peculiar to the southern and western pueblo area,

and while of later growth, should not be regarded as an evolution from

the circular kiva. Several authors have found in circular kivas

survivals of nomadic architectural conditions, while the position of

these rooms, in nearly every instance in front of the other rooms of the

cliff-dwelling, has led others to accept the theory that they were

later additions to the village, which should be ascribed to a different

race. It would seem that this hypothesis hardly conforms to facts, as

some kivas have secular rooms in front of them which show evidences of

later construction. The strongest objection to the theory that kivas are

modified houses of nomads is the style of roof construction.

KIVA A

This room (pl; 13), which is the most northerly of

all of the ceremonial rooms of Spruce-tree House, is, the author

believes, the oldest. In construction this is a remarkable chamber.

It is built directly under the cliff, which forms part of its walls. In

addition to its site the remarkable features are its double walls, and

its floor on the level of the roofs of the other kivas. Although this

kiva is not naturally subterranean, the earth and walls built up around

it make it to all intents below the surface of the ground.

It appears from the arrangement of walls and

banquettes that there is here presented an example of one room

constructed inside of another, the inner room utilizing for its wall a

portion of the outer. The inner room is more nearly circular than the

outer in which it was subsequently built. In this inner room as in other

kivas there are six banquettes, and the same number of pedestals to

support the roof. Three of these pedestals are common to both rooms. The

floor of this room shows nothing peculiar. It has a fire hole, a sipapu,

and a deflector, or low wall between the fire hole and the entrance into

the horizontal passageway of the ventilator. The ventilator itself

opens just outside the west wall through a passageway, the walls of

which stand on the wall of a neighboring room. No plaza of any

considerable size surrounded the top of this kiva.

In order to get an idea as to how many rectangular

rooms naturally accompany a single kiva, the author examined the ground

plans of such cliff-dwellings as are known to have but one circular

kiva, the majority of these being in the Chelly canyon. While it was not

possible to determine the point satisfactorily, it was found that in

several instances the circular kiva lies in the middle of several rooms,

a fact which would seem to indicate that it was built first and that the

square rooms were added later. Several clusters of rooms, each cluster

having one kiva, closely resemble kiva A and its surroundings, in both

form and structure.

KIVA B

The walls of this subterranean room had escaped all

previous observers. They are very much dilapidated, being wholly

concealed when work of excavation began. A large old cedar tree growing

in the middle of this room led the author to abandon its complete

excavation, which promised little return either in enlarging our knowledge

of the ground plan of Spruce-tree House or in shedding additional light

on the culture of its prehistoric inhabitants.

KIVAS C AND D

The two kivas, C and D, the roofs of which form the

greater part of plaza C, logically belong together in our consideration.

One of these rooms, C, was roofed over by the author, who followed as a

model the roofs of the two kivas of the House with the Square Tower

(Peabody House); the other shows a few log supports of an original

roof—the only Spruce-tree House kiva of which this is true.

Not only was the roof of the kiva restored but its

walls were well repaired, so that it now presents all the essential

features of an ancient kiva. On one of the banquettes of this room the

author found a vase which was evidently a receptacle for pigments or

other ceremonial paraphernalia.

Kiva D has a passageway leading into room 26 and a

second opening in the west wall on the floor level, besides a

ventilator of the type common to all kivas. The top of the opening in

the west wall appears covered with a flat stone in one of the

photographic views (plate 11).

The wall in front of the village in the neighborhood

of kivas C and D was wholly concealed by debris when work was begun on

this part of the ruin. Excavation of this debris showed that opposite

each kiva there was an opening with which the ventilator is believed

formerly to have been connected. There seems to have been a low-storied

house, possibly a cooking-place, provided with a roof, in an interval

between kivas C and D; in the floor of the plaza at this point a

well-made fire hole was uncovered.

KIVA E

Kiva E is one of the finest which was excavated,

showing all the typical structures of these characteristic rooms; it

almost fills the plaza in which it is situated. The exceptional feature

of this room is a passageway through the west wall. Room 35 may have

been the house of a chief or of a priest who kept in it his masks or

other ceremonial paraphernalia. A similar opening in the wall of one of

the Hopi kivas communicates with a dark room in which are kept altars

and other ceremonial objects. When such a passageway into a dark chamber

is not in use it is closed by a slab of stone.

KIVA F

Kiva F might be designated the Spruce-tree kiva from

the large spruce tree that formerly grew near its outer wall. Its stump

is now visible, but the tree lies extended in the canyon.

The walls of this kiva were poorly preserved, and

only two of the pedestals were in place. The walls were repaired

and the roof restored. This room is situated outside the walls, and in

that respect recalls kiva B, described above. The ventilator opening of

this kiva is situated on the south instead of on the west side of the

room, as is the rule in other kivas. The large size of this room would

indicate that it was of great importance in the religious ceremonials

of the prehistoric inhabitants of Spruce-tree House, but all indications

point to its late construction.a

aAn examination of the best of previous maps of

Spruce-tree House shows only a dotted line to indicate the location of

this kiva.

KIVA G

Kiva G was so well preserved that its walls were

thoroughly restored; it now stands as typical of one of these rooms in

which the several characteristic features may be seen. For the guidance

of visitors, letters or numbers accompanied by explanatory labels were

painted by the author on the walls of the kiva.

Kiva G lies just below and in front of the round

tower of Spruce-tree House, which is situated in the neighborhood of the

main court, and may therefore be looked on as one of the most important

kivas in the cliff-dwelling.a The solid stone floor of this room had

been cut down about 8 inches.

aIt has no doubt occurred to others, as to the

author, that the number of Spruce-tree House kivas is a multiple of

four, the number of horizontal cardinal points. Later it may be found

that there is some connection between them and world-quarter clan

ownership, or it may be that the agreement in numbers is purely a

coincidence.

KIVA H

Kiva H, the largest in Spruce-tree House, contained

some of the best specimens excavated by the author. Its shape is oval

rather than circular, and it fills the whole space inclosed by walls of

rooms on three sides. In the neighborhood of kiva H is a comparatively

spacious plaza which is bounded on the front by a low wall, now repaired,

and on the other sides are high rooms. The plaza containing this

kiva was ample for ceremonial dances which undoubtedly formerly

occurred in it. The walls of kiva H formerly had a marked pinkish color,

showing no sign of blackening by smoke except in places. Charred roof

beams were excavated at one place, however, and charcoal occurred deep

under the debris that filled this room.

CIRCULAR ROOMS OTHER THAN KIVAS

There are two rooms (nos. 54, 69) of circular shape

in Spruce-tree House, one of which resembles the "tower" in the Cliff

Palace. This room (no. 54) is situated to the right hand of the main

court above referred to, into which it projects without attachment

except on one side. Its walls have two small windows or openings which

have been called doorways, and are of a single story in height. This

tower was apparently ceremonial in character.

It is instructive to mention that remains of a fire

hole containing wood ashes occur in the floor on one side of this room,

and that the walls are pierced with several small holes opening at an

angle. Only foundations remain of the other circular room. It was

situated on the south side of the open space containing kiva H and

formed a bastion at the north end of the front wall. The floor of this

room was wholly covered with fallen debris and its ground plan was

wholly concealed when the excavations began; it was only

with considerable difficulty that the foundation walls could be

traced.

CEREMONIAL ROOM OTHER THAN KIVA

While the circular subterranean rooms above mentioned

are believed to be the most common ceremonial chambers, there are

others in the cliff-dwellings which were undoubtedly used for similar

purposes. One of these, designated room 12, adjoins the mortuary room

(11) and opens on the plaza C, D. In some respects the form of this room

is similar to an "estufa of singular construction" described and

figured in Nordenskiöld's account of Cliff Palace. Certain distinctive

characters of this room separate it on one side from a kiva and on the

other from a dwelling. In the first place, it lacks the circular form

and subterranean site. The six pedestals which universally support the

roofs are likewise absent. In fact they are not needed because in this

room the top of the cave serves as the roof. A bank extends around three

sides of the room, the fourth side being the perpendicular wall of the

cliff. In the southeast corner is an opening, which recalls that in the

"estufa of singular construction" described by Nordenskiöld.a

aThe Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, p. 63.

MORTUARY ROOM

Room 9 may be designated a mortuary room from the

fact that at least four human skeletons and accompanying offerings have

been found in its floor. Three of those, excavated several years ago,

were said to have been infants; the skull of one of these was figured

and described by Prof. G. Retzius, in Nordenskiöld's memoir. The

skeleton found by the author was that of an adult and was accompanied by

mortuary offerings. The skull and some of the larger bones were well

preserved.b Evidently the doorway of this room had been walled up and

there are indications that the burials took place at intervals, the last

occurring before the desertion of the village.

bIn clearing the kivas several fragments of human bones and skulls were

found by the author. The horizontal passageways, called ventilators, of

four of the kivas furnished a

single broken skull each, which had not been buried with care.

The presence of burials in the floors of rooms in

Spruce-tree House was to be expected, as the practice of thus disposing

of the dead was known from other ruins of the Park; but it has not been

pointed out that we have in this region good evidence of several

successive internments in the same room. The existence of this

intramural burial room in the south end of the ruin is one of the facts

that can be adduced pointing to the conclusion that this part of the

ruin is very old.

SMALL LEDGE-HOUSES

Not far from the Spruce-tree House, situated in the

same canyon, there are small one-room houses perched on narrow ledges

situated generally a little higher than the cave containing the main

ruin. Although it is difficult to enter some of these

houses, members of the author's party visited all of them, and two of

the workmen slept in a small ledge-house on the west side of the canyon.

Except in rare cases these smaller houses can not be considered

dwellings; they may have been used for storage, although it is more

than likely that they were resorted to by priests when they wished to

pray for rain or to perform certain ceremonies. The ledge-houses form a

distinct type of ruin; they are rarely multiple-chambered and therefore

are not capacious enough for more than one family.

STAIRWAYS

There are two or three old stairway trails in the

neighborhood of Spruce-tree House. These consist of a succession of

holes for hands and feet, or of a series of pits cut in the face of the

cliff at convenient distances. One of these ancient trails is situated

on the west side of the canyon not far from the modern trail to the

spring; the other lies on the east side a few feet north of the ruin.

Both of these trails were appropriately labeled for the convenience of

future visitors. There is still another ancient trail along the east

canyon wall south of the ruin. Although all these trails are somewhat

obscure, it is hoped that they can be readily found by means of the

labels posted near them.

REFUSE-HEAPS

In the rear of the buildings are two large open

spaces which, from their positions relative to the main street, may be

called the northern and southern refuse-heaps. They merit more than

passing consideration. The former, being the larger, has not yet been

thoroughly cleared out, although pretty well dug over before the

repair work was begun. The author completely cleared out the southern

refuse-heap and excavated to its floor.a

aFrom the great amount of bird-lime and bones in

these heaps it has been supposed that turkeys were domesticated and kept

in these places.

The southern recess opens directly into the main

street and is flooded with light. Its floor is covered with large

fragments of rock that have fallen from the cliff above. The spaces

between these bowlders were filled with debris and the bowlders

themselves were covered with the same accumulations the removal of which

was no small task.

The rooms and refuse-heaps of Spruce-tree House had

been pretty thoroughly ransacked for specimens by those who preceded the

author, so that few minor antiquities were expected to come to light in

the excavation and repair work. Notwithstanding this, however, a fair

collection, containing some unique specimens and many representative

objects, was made, and is now in the National Museum where it will be

preserved and be accessible to all students. Considering the fact that

most of the specimens previously abstracted from this ruin have been

scattered in all directions and are now in many hands, it is doubtful

whether a collection of any considerable size from Spruce-tree House

exists in any other public museum. In order to render this account more

comprehensive, references are made in the following pages to objects

from Spruce-tree House elsewhere described, now in other collections.

These references, quoted from Nordenskiöld, the only writer on this

subject, are as follows:

Plate XVII:2. a and b. Strongly flattened cranium of

a child. Found in a room in Sprucetree House.

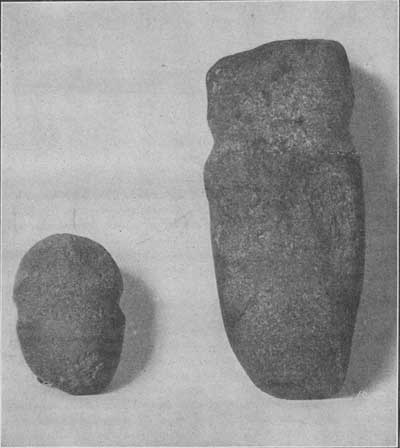

Plate XXXIV:4. Stone axe of porphyrite. Sprucetree

House.

Plate XXXV: 2. Rough-hewn stone axe of quartzite.

Sprucetree House.

Plate XXXIX: 6. Implement of black slate. Form

peculiar (see the text). Found in Sprucetree House.

[In the text the last-mentioned specimen is again

referred to, as follows:]

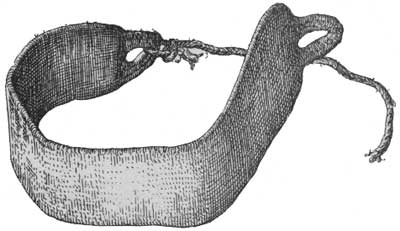

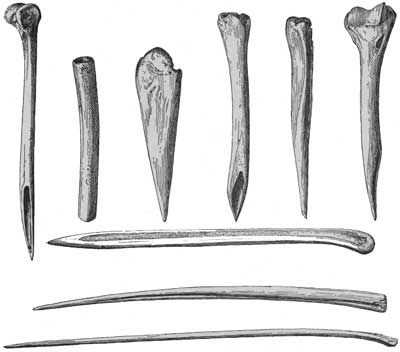

I have still to mention a number of stone implements

the use of which is unknown to me, first some large (15-30 cm.), flat,

and rather thick stones of irregular shape and much worn at the edges

(Pl. XXXIX: 4, 5), second a singular object consisting of a thin slab of

black slate, and presenting the appearance shown in Pl. XXXIX: 6. My

collection contains only one such implement, but among the objects in

Wetherill's possession I saw several. They are all of exactly the same

shape and of almost the same size. I cannot say in what manner this slab

of slate was employed. Perhaps it is a last for the plaiting of sandals

or the cutting of moccasins. In size it corresponds pretty nearly to the

foot of an adult.

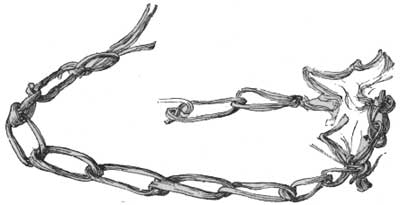

Plate XL: 5. Several ulnae and radii of

birds (turkeys) tied on a buckskin string and probably used as an

amulet. Found in Sprucetree House.

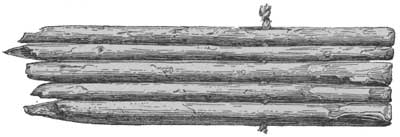

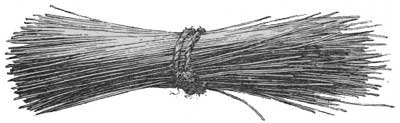

Plate XLIII: 6. Bundle of 19 sticks of hard wood,

probably employed in some kind of knitting or crochet work. The pins are

pointed at one end, blunt at the other, and black with wear. They are

held together by a narrow band of yucca. Found in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLIV: 2. Similar to the preceding basket, but

smaller. Found in Sprucetree House. . . .

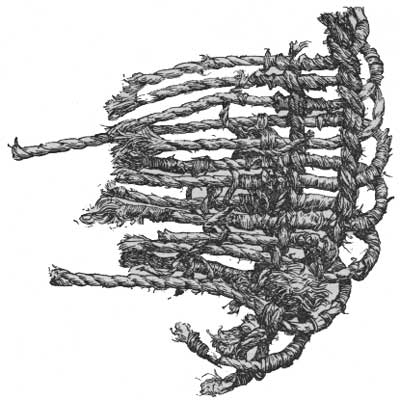

[The "preceding basket" is thus described in

explanation of the figure (Pl. XLIV: 1) :] Basket of woven yucca in two

different colors, a nest pattern being thus attained. The strips of

yucca running in a vertical direction are of the natural yellowish

brown, the others (in horizontal direction) darker. . . .

Plate XLV: 1(95) and 2(663): Small baskets of yucca,

of plain colour and of handsomely plaited pattern. Found: 1 in ruin 9, 2

in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLVIII: 4(674). Mat of plaited reeds,

originally 1.2 X 1.2 in., but damaged in transportation. Found in

Sprucetree House.

It appears from the foregoing that the following

specimens have been described and figured by Nordenskiöld, from

Spruce-tree House: (1) A child's skull; (2) 2 stone axes; (3) a slab of

black slate; (4) several bird bones used for amulet; (5) bundle of

sticks; (6) 2 small baskets; (7) a plaited mat.

In addition to the specimens above referred to, the

majority of which are duplicated in the author's collection, no objects

from Spruce-tree House are known to have been described or figured

elsewhere, so that there are embraced in the present account practically

all printed references to known material from this ruin. But there is no

doubt that other specimens as yet unmentioned in print still exist in

public collections in Colorado, and later these also may be described

and figured. From the nature of the author's excavations and method of

collecting, little hope remains that additional specimens may be

obtained from rooms in Spruce-tree House, but the northern refuse-heap

situated at the back of the cavern may yet yield a few, good objects.

This still awaits complete scientific excavation.

The author's collection from Spruce-tree House, the

choice specimens of which are now in the National Museum, numbers

several hundred objects. All the duplicates and heavy specimens, about

equal in number to the lighter ones, were left at the ruin where they

are available for future study. These are mostly stone mauls, metates

and large grinding implements, and broken bowls and vases. The absence

from Spruce-tree House of certain characteristic objects widely

distributed among Southwestern ruins is regarded as worthy of comment.

It will be noticed in looking over the author's collection that there

are no specimens of marine shells, or of turquoise ornaments or obsidian

flakes, from the excavations made at Spruce-tree House. This fact is

significant, meaning either that the former inhabitants of this village

were ignorant of these objects or that the excavators failed to find

what may have existed. The author accepts the former explanation, that

these objects were not in use by the inhabitants of Spruce-tree House,

their ignorance of them having been due mainly to their restricted

commercial dealings with their neighbors.

Obsidian, one of the rarest stones in the

cliff-dwellings of the Mesa Verde, as a rule is characteristic of very

old ruins and occurs in those having kivas of the round type, to the

south and west of that place.

It is said that turquoise has been found in the Mesa

Verde ruins. The author has seen a beautiful bird mosaic with inlaid

turquoise from one of the ruins near Cortez in Montezuma valley. This

specimen is made of hematite with turquoise eyes and neckband of the

same material; the feathers are represented by stripes of inlaid

turquoise. Also inlaid in turquoise in the back is an hour-glass figure,

recalling designs drawn in outline on ancient pottery.

The absence of bracelets, armlets, and finger rings

of sea shells, objects so numerous in the ruins along the Little

Colorado and the Gila, may be explained by lack of trade, due to culture

isolation. The people of Mesa Verde appear not to have come in contact

with tribes who traded these shells, consequently they never obtained

them. The absence of culture connection in this direction tells in favor

of the theory that the ancestors of the Mesa Verde people did not come

from the southwest or the west, where shells are so abundant. Although

not proving much either way by itself, this theory, when taken with

other facts which admit of the same interpretation, is significant. The

inhabitants of Spruce-tree House (the same is true of the other Mesa

Verde people) had an extremely narrow mental horizon. They obtained

little in trade from their neighbors and were quite unconscious of the

extent of the culture of which they were representatives.

POTTERY

The women of Spruce-tree House were expert potters

and decorated their wares in a simple but artistic manner. Until we have

more material it would be gratuitous to assume that the ceramic art

objects of all the Mesa Verde ruins are identical in texture, colors,

and symbolism, and the only way to determine how great are the

variations, if any, would be to make an accurate comparative study of

pottery from different localities. Thus far the quantity of material

available does not justify comparison even of the ruins of this mesa,

but there is a good beginning of a collection from Spruce-tree House.

The custom of placing in graves offerings of food for the dead has

preserved several good bowls, and although whole pieces are rare

fragments are found in abundance. Eighteen earthenware vessels,

including those repaired and restored from fragments, rewarded the

author's excavations at Spruce-tree House. Some of these vessels bear a

rare and beautiful symbolism which is quite different from that known

from Arizona. The few plates (16-20) here given to illustrate these

symbols are offered more as a basis for future study and comparisons

than as an exhaustive representation of ceramics from one ruin.

The number and variety of pieces of pottery figured

from the Mesa Verde cliff-dwellings have not been great. An examination

of Nordenskiöld's memoir reveals the fact that he represents about

50 specimens of pottery; several of these were obtained by purchase, and

others came from Chelly canyon, the pottery of which is strikingly like

that of Mesa Verde. The majority of specimens obtained by

Nordenskiöld's excavations were from Step House, not a single

ceramic object from Spruce-tree House being figured. So far as the

author can ascertain, the ceramic specimens here considered are the

first representatives of this art from Spruce-tree House that have been

described or figured, but there may be many other specimens from this

locality awaiting description and it is to be hoped that some day these

may be made known to the scientific world.

FORMS

Every form of pottery represented by

Nordenskiöld, with the exception of that which he styles a

"lamp-shaped" vessel and of certain platter forms with indentations,

occurs in the collection here considered.

Nordenskiöld figures a jar provided with a lid,

both sides of which are shown.a It would seem that this lid (fig.

1),b unlike those provided with knobs, found by the author, had

two holes near the center. The decoration on the top of the lid of one

of the author's specimens resembles that figured by Nordenskiöld,

but other specimens differ from his as shown in figure 1. The specimens

having raised lips and lids are perforated in the edges of the openings,

with one or more holes for strings or handles. As bowls of this form are

found in sacred rooms they would seem to have been connected with

worship. The author believes that they served the same purposes as the

netted gourds of the Hopi. Most of the ceramic objects in Spruce-tree

House were in fragments when found.c Some of these objects have

been repaired and it is remarkable that so much good material for the

study of the symbolism has been obtained in this way.

aSee The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, pls.

XXVIII, XXIX: 7.

bThe text figures which appear in this paper were drawn from

nature by Mrs. M. W. Gill, of Forest Glen, Md.

cThe author is greatly indebted to Mr. A. V. Kidder for aid

in sorting and labeling the fragments of pottery, without his assistance

in the field it would have been impossible to repair many of these

specimens.

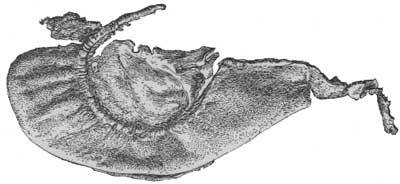

FIG. 1. Lid of jar.

|

Black and white ware is the most common and the

characteristic painted pottery, but fragmentary specimens of a reddish

ware occur. One peculiarity in the lips of food bowls from Spruce-tree

House (pls. 16-18) is that their rims are flat, instead of rounded as in

more western prehistoric ruins, like Sikyatki. Food bowls are rarely

concave at the base.

No fragments of glazed pottery were found, although

the surfaces of some species were very smooth and glossy from constant

rubbing with smoothing stones. Several pieces of pottery were unequally

fired, so that a vitreous mass, or blotch, was evident on one side.

Smooth vessels and those made of coiled ware, which were covered with

soot from fires, were evidently used in cooking.

FIG. 2. Repaired pottery.

|

Several specimens showed evidences of having been

broken and afterwards mended by the owners (fig. 2); holes were drilled

near the line of fracture and the two parts tied together; even the

yucca strings still remain in the holes, showing where fragments were

united. In figure 3 there is represented a fragment of a handle of an

amphora on which is tied a tightly-woven cord.

FIG. 3. Handle with attached cord.

|

Not a very great variety of pottery forms was brought

to light in the operations at Spruce-tree House. Those that were found

are essentially the types common throughout the Southwest, and may be

classified as follows: (1). Large jars, or ollas; (2) flat food bowls;

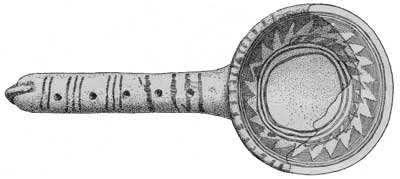

(3) cups and mugs; (4) ladles or dippers (fig. 4); (5) canteens; (6)

globular bowls. An exceptional form is a globular bowl with a raised lip

like a sugar bowl (pl. 19, f). This form is never seen in other

prehistoric ruins.

STRUCTURE

Classified by structure, the pottery found in the

Spruce-tree House ruin falls into two groups, coiled ware and smooth

ware, the latter either with or without decoration. The white ware has

black decorations.

The bases of the mugs (pl. 19) from Spruce-tree

House, like those from other Mesa Verde ruins, have a greater diameter

than the lips. These mugs are tall and their handles are of generous

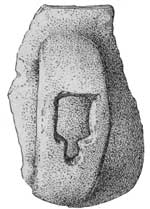

size. One of the mugs found in this ruin has a T-shaped hole in its

handle (fig. 5), recalling in this particular a mug collected in 1895 by

the author at Awatobi, a Hopi ruin.

The most beautiful specimen of canteen found at

Spruce-tree House is here shown in plate 20.

FIG. 4. Ladle.

|

The coiled ware of Spruce-tree House, as of all the

Mesa Verde ruins, is somewhat finer than the coiled ware of Sikyatki.

Although no complete specimen was found, many fragments were collected,

some of which are of great size. This kind of ware was apparently the

most abundant and also the most fragile. As a rule these vessels show

marks of fire, soot, or smoke on the outside, and were evidently used as

cooking vessels. On account of their fragile character they could not

have been used for carrying water, for, with one or two exceptions, they

would not be equal to the strain. In decoration of coiled ware the women

of Spruce-tree House resorted to an ingenious modification of the coils,

making triangular figures, spirals, or crosses in relief, which were

usually affixed to the necks of the vessels.

FIG. 5. Handle of mug.

|

The symbolism on the pottery of Spruce-tree House is

essentially that of a cliff-dwelling culture, being simple in general

characters. Although it has many affinities with the archaic symbols of

the Pueblos, it has not the same complexity. The reason for this can be

readily traced to that same environmental influence which caused the

communities to seek the cliffs for protection. The very isolation of the

Mesa Verde cliff-dwellings prevented the influx of new ideas and

consequently the adoption of new symbols to represent them. Secure in

their cliffs, the inhabitants were not subject to the invasion of

strange clans nor could new customs be introduced, so that conservatism

ruled their art as well as their life in general. Only simple symbols

were present because there was no outside stimulus or competition to

make them complex.

On classification of Spruce-tree House pottery

according to technique, irrespective of its form, two divisions appear:

(1) Coiled ware showing the coils externally, and (2) smooth ware with

or without decorations. Structurally both divisions are the same,

although their outward appearance is different.

The smooth ware may be decorated with incised lines

or pits, but is painted often in one color. All the decorated vessels

obtained by the author at Spruce-tree House belong to what is called

black-and-white ware, by which is meant pottery having a thin white slip

covering the whole surface upon which black pictures are painted.

Occasionally fragments of a reddish brown cup were found, while red ware

bearing white decorative figures was recovered from the Mesa Verde; but

none of these are ascribed to Spruce-tree House or were collected by the

author. The general geographical distribution of this black and white

ware, not taking into account sporadic examples, is about the same as

that of the circular kivas, but it is also found where circular kivas

are unknown, as in the upper part of the valley of the Little Colorado.

The black-and-white ware of modern pueblos, as Zu–i

and Hano, the latter the Tewan pueblo among the Hopi, is of late

introduction from the Rio Grande; prehistoric Zu–i ware is unlike that

of modern Zu–i, being practically identical in character with that of

the other ancient pueblos of the Little Colorado and its tributaries.

DECORATION

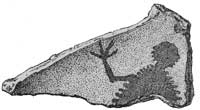

FIG. 6. Fragment of pottery.

|

As a rule, the decoration on pottery from Spruce-tree

House is simple, being composed mainly of geometrical patterns. Life

forms are rare, when present consisting chiefly of birds or rude figures

of mammals painted on the outside of food bowls (fig. 6). The

geometrical figures are principally rectilinear, there being a great

paucity of spirals and curved lines. The tendency to arrange rows of

dots along straight lines is marked in Mesa Verde pottery and occurs

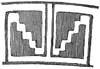

also in dados of house walls. There are many examples of stepped or

terraced figures which are so arranged in pairs that the spaces between

the terraces form zigzag bands, as shown in figure 7. A band extending

from the upper left hand, to the lower right hand, angle of the

rectangle that incloses the two terraced figures, may be designated a

sinistral, and when at right angles a dextral, terraced figure (fig. 8).

Specimens from Spruce-tree House show considerable modification in these

two types.

FIG. 7. Zigzag ornament.

|

With exception of the terrace the triangle (fig. 9)

is possibly the most common geometrical decoration on Spruce-tree House

pottery. Most of the triangles may be bases of terraced figures, for by

cutting notches on the longer sides of these triangles, sinistral or

dextral stepped figures (as the case may be) result.

The triangles may be placed in a row, united in

hourglass forms, or distributed in other ways. These triangles may be

equilateral or one of the angles may be very acute. Although the

possibilities of triangle combinations are almost innumerable the

different forms can be readily recognized. The dot is a common form of

decoration, and parallel lines also are much used. Many bowls are

decorated with hachure, and with line ornaments mostly rectilinear.

FIG. 8. Sinistral and dextral stepped figures.

|

The volute plays a part, although not a conspicuous

one, in Spruce-tree House pottery decoration. Simple volutes are of two

kinds, one in which the figure-coils follow the direction of the hands

of the clock (dextral); the other, in which they take an opposite

direction (sinistral). The outer end of the volute may terminate in a

triangle or other figure, which may be notched, serrated, or otherwise

modified. A compound sinistral volute is one which is sinistral until it

reaches the center, when it turns into a dextral volute extending to the

periphery. The compound dextral volute is exactly the reverse of the

last-mentioned, starting as dextral and ending as sinistral. If, as

frequently happens, there is a break in the lines at the middle, the

figure may be called a broken compound volute. Two volutes having

different axes are known as a composite volute, sinistral or dextral as

the case may be.

The meander (fig. 10) is also important in

Spruce-tree House or Mesa Verde pottery decoration. The form of meander

homologous to the volute may be classified in the same terms as the

volute, into (1) simple sinistral meander; (2) simple dextral meander;

(3) compound sinistral meander; (4) compound dextral meander; and (5)

composite meander. These meanders, like the volutes, may be accompanied

by parallel lines or by rows of dots enlarged, serrated, notched, or

otherwise modified.

FIG. 9. Triangle ornament.

|

In some beautiful specimens a form of hachure, or

combination of many parallel lines with spirals and meanders, is

introduced in a very effective way. This kind of decoration is very rare

on old Hopi (Sikyatki) pottery, but is common on late Zu–i and Hano

ceramics, both of which are probably derived from the Rio Grande region.

Lines, straight or zigzig, constitute important

elements in Spruce-tree House pottery decoration. These may be either