The route chosen by the author for visiting the ruins

of the Navaho National Monument is via Flagstaff and Tuba, the distance

being not far from 200 miles to Marsh pass and 10 miles beyond to the

largest cliff-dwellings. Although the wagon road is long, requiring a

journey of at least five days, it may be traversed with carriage or

buckboard, the sandy stretch between Tuba and Red Lake being the most

difficult. The trail from Marsh pass to the great cliff-dwellings,

although now passable only on horseback, could be made into a wagon road

at small expense.

The nature of the cliffs in which the ruins of the

Navaho Monument are situated favored the construction of cliff-dwellings

rather than of open pueblos in this region. These cliffs are full of

caverns, large and small, presenting much the same condition as the

cliffs of the red sandstone elsewhere in the Southwest, as the Mesa

Verde, Canyon de Chelly, the Red Rocks south of Flagstaff, and other

sections where caverns abound. Fragments of fallen rocks present good

plane surfaces for walls of masonry, and there is abundant clay for

plastering. Trees suitable for rafters and beams are not wanting. In

short, all conditions are favorable for stone and adobe houses in the

cliffs. The neighboring Sethlagini mesa is of different geological

formation; in it are no caverns, the mesa top is broad, and ruins

thereon are necessarily open pueblos. The effect of difference in

geological structure is nowhere more evident than in these adjacent

formations.

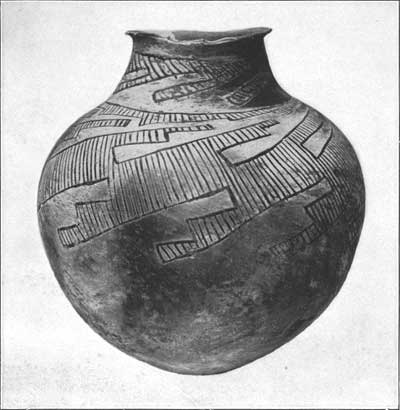

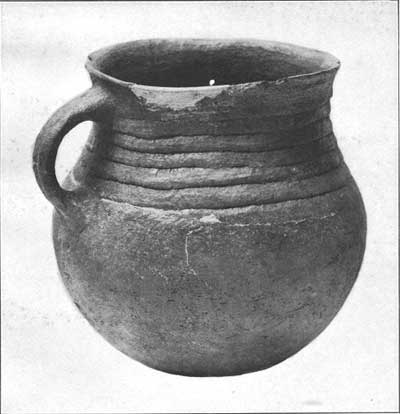

Plate 18. POTTERY FROM NAVAHO NATIONAL

MONUMENT (a large black-and-white vase [Cat No. 257774, height 17

inches] (top); b large vase with handle [Cat No. 257787, height

8-1/2 inches] (bottom))

|

If environment has had so marked an influence on the

character of building, we can readily see how it has affected arts and

crafts. We can hardly imagine a people living any length of time in this

region without being mentally influenced by the precipitous cliffs that

rise on all sides. The summits of these heights are eroded into

fantastic shapes resembling animals or grotesque human forms. The

constant presence of these marvelous forms, of awe-inspiring size and

weird appearance, exerted a profound influence on the supernatural ideas

of the inhabitants. Here were born many conceptions of earth gods and

the like, survivals of which still remain among the Hopi.

As a rule the cliff-houses are not situated in sight

of the main stream, but are hidden away in secluded side canyons,

approached by narrow entrances, their sites having been determined no

doubt by the position of the springs with their constant water

supply.

Almost every side canyon, even in a dry season, has

its spring of water which, trickling out of the rocks, follows the

canyon bed until it is finally drunk up by the thirsty sands. Often

water seeps out of a soft stratum of rock in the cave itself, where it

was gathered in artificial reservoirs that in ancient times furnished an

adequate supply for the inhabitants. One feature of these side canyons

is that they enlarge into basins surrounded on all sides by lofty

cliffs. Many of these basins are so hidden that they can be discovered

only by following dry stream-beds from their junction with the creeks.

How many of these basins are still undiscovered no one can yet tell. In

these basins now covered with bushes the aboriginal farms were probably

situated.

As the width of the valley of Laguna creek from Marsh

pass to the point where the stream receives its largest branches on the

left bank varies, the amount of arable land is greater in some places

than in others. In stretches where the stream almost washes the bases of

the ruins there could have been no extensive farming lands. The creek

meanders through the soft clay and sand which fill the valley to the

depth of many feet, forming treacherous banks that are continually

falling and changing the course of the stream, so it is quite possible

that the present configuration of the valley is very different from what

it was when the cliff-dwellings were inhabited. If the occupants once

had farms within its limits all traces of them would have long since

been obliterated. Although too much credence should not be given to

Navaho traditions, it is not unreasonable to believe that in one

particular at least they are correct. These state that, before the

introduction of sheep, grass was much higher in the level part of the

valley than at present, and formerly game (at least the mountain sheep

and the antelope) may have been more abundant. This condition would have

exerted a marked influence on the life of the cliff-dwellers.

Pictographs show that the ancient people, either here or in their former

homes, were familiar with these animals, and various objects of bone and

horn are significant in this connection.

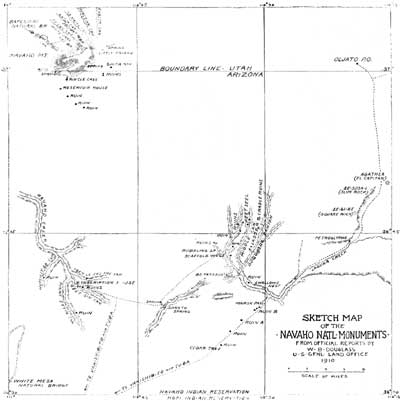

The Navaho National Monument (see sketch map, pl. 22)

contains two kinds of ruins,a cliff-dwellings and pueblos. Most

of the latter are situated on promontories or on low hills. The

structural features of the cliff-dwellings are characteristic, their

walls being constructed of stone or adobe built against, rarely free

from, vertical faces of the cliff.

aThe writer was not able to determine the exact site of the

traditional Tokonabi, but believes one is justified in considering the

ruins visited to be prehistoric houses of the snake (Flute), Horn, and

other Hopi clans whose descendants now live in Walpi.

There are two types of kivas, one circular and

subterranean, allied to those of the Mesa Verde, the other rectangular,

above ground, entered from the sides.

The masonry of these northern ruins is crude,

resembling that of modern Walpi. The component stones are neither

dressed nor smoothed, but the walls are sometimes plastered. There is a

great similarity in architecture. No round towersb relieve the

monotony or impart picturesqueness to the buildings. The walls of ruined

pueblos in this region and the ceramic remains closely resemble those at

Black Falls on the Little Colorado. A prominent feature of the walls is

a jacal construction in which the mud is plastered on wattling

between upright poles. The ends of many of these supports project high

above the ground, constituting a characteristic feature of the ruins.

This method of wall construction is unknown at Black Falls or at Walpi,

but survives in modified form in one or more Oraibi kivas and in one at

least of the Mesa Verde ruins.c It has been described by Mr.

Cosmos Mindeleff as common to several ruins in the Canyon de Chelly.

b While circular subterranean kivas are found in some of the

ruins, none of these have the six pilasters so common higher up on the

San Juan, nor hove these rooms ventilators like those of Spruce-tree

House. Some of the ruins have rectangular kivas, above ground, entered

from one side.

cThe best example of walls of this kind is found in an

undescribed cliff-ruin in the canyon southwest of Cliff Palace.

The key to the culture of the people from which the

cliff-dweller culture was derived is probably the kiva, which furnishes

also a good basis for the classification of the Pueblos and

cliff-dwellers into subordinate groups.

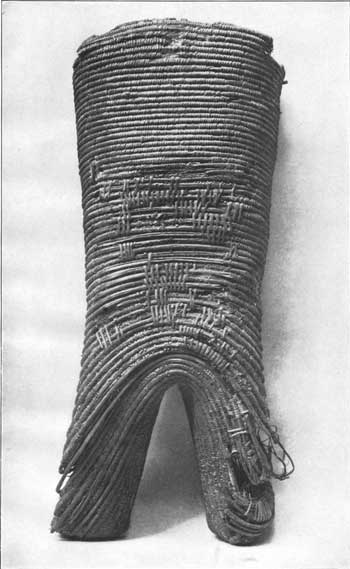

Plate 19. CLIFF-DWELLERS CRADLE—FRONT

(Dimensions; length, 22 inches; breadth, 9 inches; diameter, 6

inches)

|

Plate 20. CLIFF-DWELLERS CRADLE—REAR

|

Plate 21. CLIFF-DWELLERS CRADLE—SIDE

|

Architecturally the kiva reached its highest

development in the Mesa Verde region, where it is a circular

subterranean room with pilasters and banquettes, ventilators and

deflectors, fireplaces and ceremonial openings, the features of which

have been described elsewhere. As we follow the San Juan down to its

junction with the Colorado we find a gradual simplification of the

circular type of kiva by the elimination of pilasters, ventilators, and

other features, the round kiva being here represented by rooms in which

almost the only architectural feature remaining is the large banquette.

The question naturally arising in this connection is, whether the

circular kiva in the eastern region is a development of that simpler

form existing in the western or whether the latter is a degenerate form

of the eastern. In other words, does the evidence show that this

particular modification spread from the east down the San Juan or from

the west up the river to the east? In this connection it may be urged

that originally the form of circular kiva lacking pilasters extended

along the entire course of the San Juan and that the kivas of the Mesa

Verde became highly specialized forms in which pilasters were developed,

while those lower down the river remained the same. We can not

definitely answer either of these questions, but taken with other

evidence it would seem that the circular form of kiva originated in the

eastern section and gradually extended westward.

The modern Hopi rectangular form of ceremonial room

situated underground seems in some instances to have derived certain

features from the circular subterranean kiva.

The chief kiva at Walpi, that used by the Snake

fraternity, is rectangular and subterranean, while that used by the

Flute priests, which is practically a ceremonial room, is a chamber

entered by a side doorway. It is suggested that the Snake kiva at Walpi

was derived from the circular subterranean kiva of Tokonabi, the former

home of the Snake clan in northern Arizona, and that the Flute chamber

was developed from the rectangular rooms in the same ruins. The old

question, so often considered by Southwestern archeologists, whether the

circular subterranean kiva was derived from the rectangular or vice

versa, seems to the writer to be somewhat modified by the fact that

ceremonial rooms of both forms exist side by side in many ancient

cliff-dwellings. From circular subterranean kivas in some instances

developed square kivas, but the latter are sometimes the direct

development of square rooms; the determination of the original form can

best result from a study of clans and their migrations.a

>aIt is generally the custom to speak of the

rectangular subterranean rooms of Walpi as kivas, while the square or

rectangular rooms above ground, in which equally secret rites are

performed, are not so designated. Both types are ceremonial rooms, but

for those not subterranean the term kihu (clan ceremonial room), instead

of kiva, is appropriate.

Naturally the questions one asks in regard to these

ruins are:

Why did the inhabitants build in these cliffs? Who

were the ancient inhabitants? When were these dwellings inhabited and

deserted?

It is commonly believed that the caves were chosen

for habitations because they could be better defended than villages in

the open. This is a good answer to the first question, so far as it

goes, although somewhat imperfect. The ancients chose this region for

their homes on account of the constant water supply in the creek and the

patches of land in the valley that could be cultivated. This was a

desirable place for their farms. Had there been no caves in the cliffs

they would probably have built habitations in the open plain below. They

may have been harassed by marauders, but it must be borne in mind that

their enemies did not come in great numbers at any one time. Defense was

not the primary motive that led the sedentary people of this canyon to

utilize the caverns for shelter. Again, the inroads of enemies never led

to the abandonment of these great cliff houses, if we can impute valor

in any appreciable degree to the inhabitants. Fancy, for instance, the

difficulty, or rather improbability, of a number of nomadic warriors

great enough to drive out the population of Kitsiel, making their way up

Cataract canyon and besieging the pueblo. Such an approach would have

been impossible. Marauders might have raided the Kitsiel cornfields, but

they could not have dislodged the inhabitants. Even if they had

succeeded in capturing one house but little would have been gained, as

it was a custom of the Pueblos to keep enough food in store to last more

than a year. In this connection the question is pertinent. While

hostiles were besieging Kitsiel how could they subsist during any length

of time? Only with the utmost difficulty, even with aid of ropes and

ladders, can one now gain access to some of these ruins. How could

marauding parties have entered them if the inhabitants were hostile? The

cliff-dwellings were constructed partly for defense, but mainly for the

shelter afforded by the overhanging cliff, and the cause of their

desertion was not due so much to predatory enemies as failure of crops

or the disappearance of the water supply.

The writer does not regard these ruins as of great

antiquity; some of the evidence indicates that they are of later time.

Features in their architecture show resemblances derived from other

regions. The Navaho ascribe the buildings to ancient people and say that

the ruined houses existed before their own advent in the country, but

this was not necessarily long ago. Such evidence as has been gathered

supports Hopi legends that the inhabitants were ancient Hopi belonging

to the Flute, Horn, and Snake families.

There is no evidence that cliff-house architecture

developed in these canyons, and rude structures older than these have

been found in this region. Whoever the builders of these structures

were, they brought their craft with them. The adoption of the deflector

in the rectangular ceremonial rooms called kihus implies the derivation

of these rooms from circular kivas, and all indications are that the

ancient inhabitants came from higher up San Juan river.

Many of the ruins in Canyon de Chelly situated east

of Laguna creek show marked evidence of being modern, and they in turn

are not so old as those of the Mesa Verde. If the ruins become older as

we go up the river the conclusion is logical that the migration of the

San Juan culture was down the river from east to west, rather than in

the opposite direction. The scanty traditions known to the author

support the belief in a migration from east to west, although there were

exceptional instances of clan movements in the opposite direction. The

general trend of migration would indicate that the ancestral home of the

Snake and Flute people was in Colorado and New Mexico.

Plate 22. SKETCH MAP OF THE NAVAHO NATIONAL

MONUMENTS (click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

It is evident from the facts here recorded that the

ruins in the Navaho National Monument contain most important, most

characteristic, and well-preserved prehistoric buildings, and that the

problems they present are of a nature to arouse great interest in them.

Having suffered comparatively little from vandalism, these are among the

best-preserved monuments of the cliff-dwellers' culture in our

Southwest, and if properly excavated and repaired they would preserve

most valuable data for the future student of prehistoric man in North

America. It is not necessary to preserve all the ruins within this area,

but it would be well to explore the region and to locate the sites of

the ruins that it contains.