It is remarkable that this magnificent ruin (pl. 1)

so long escaped knowledge of white settlers in the neighboring Montezuma

valley. Cliff Palace is not mentioned in early Spanish writings, and,

indeed, the first description of it was not published until about

1890.

Efforts to learn the name of the white man who

discovered Cliff Palace were not rewarded with great success. According

to Nordenskiöld it was first seen by Richard Wetherill and Charley

Mason on a "December day in 1888," but several residents of the towns of

Mancos and Cortez claim to have visited it before that time. One of the

first of these visitors was a cattle owner of Mancos, Mr. James Frink,

who told the author that he first saw Cliff Palace in 1881, and as

several stockmen were with him at that time it is probable that there

are others who visited it the same year. We may conclude that Cliff

Palace was unknown to scientific men in 1880, and the most we can

definitely say is that it was first seen by white men some time in the

decade 1880-1890.a

aIt is generally stated by stockmen and others

who claim to have seen Cliff Palace "years ago," that the walls of the

buildings were much higher in the early eighties than they are at

present.

While there is considerable literature on the

cliff-dwellings of the Mesa Verde, individual ruins have not been

exhaustively described. Much less has been published on Spruce-tree

House than on Cliff Palace, which latter ruin, being the largest, has

attracted more attention than any other in the Park. As every

cliff-house has its peculiar architectural features it is well in

describing these buildings to refer to the ruins by names. This

individuality in architecture pertains likewise to specimens, the

majority of which in museums unfortunately are labeled merely "Mancos"

or "Mesa Verde." A large number of these objects probably came from

Spruce-tree House and Cliff Palace, but it is now impossible to

determine their exact derivation.

The first extended account of Cliff Palace,

accompanied with illustrations, which is worthy of special mention, was

published by Mr. F. H. Chapin, and so far as priority of publication is

concerned he may be regarded as the first to make Cliff Palace known to

the scientific world. Almost simultaneously with his article there

appeared an account of the ruin by Doctor Birdsall, followed shortly by

the superbly illustrated memoir of Baron Gustav Nordenskiöld. All these

writers adopt the name Cliff Palace, which apparently was first given to

the ruin by Richard Wetherill, one of the claimants for its discovery.

Nordenskiöld's work contains practically all that was known about Cliff

Palace up to the beginning of the summer's field work herein

described.

Mr. Chapina thus referred to Cliff Palace in a

paper read before The Appalachian Mountain Club on February 13,

1890:

After a long ride we reached a camping-ground at the

head of a branch of the left-hand fork of Cliff Canon. Hurriedly

unpacking, we hobbled the horses that were the most likely to stray far,

and taking along our photographic kit, wended our way on foot toward

that remarkable group of ruins of which I have already spoken, and which

Richard has called "the Cliff-Palace." At about three o'clock we reached

the brink of the canon opposite the wonderful structure. Surely its

discoverer had not overstated the beauty and magnitude of this strange

ruin. There it was, occupying a great oval space under a grand cliff

wonderful to behold, appearing like an immense ruined castle with dismantled

towers. The stones in front were broken away, but behind them

rose the walls of a second story; and in the rear of these, in under the

dark cavern, stood the third tier of masonry. Still farther back in the

gloomy recess, little houses rested on upper ledges. A short distance

down the canon are cosey buildings perched in utterly inaccessible

nooks. The neighboring scenery is marvelous; the view down the cañon to

the Mancos is alone worth the journey to see. We stopped to take a few

views, and then commenced the descent into the gulf below. What would

otherwise have been a hazardous proceeding, was rendered easy by using

the steps which had been cut in the wall by the builders of the

fortress. There are fifteen of these scouped-out hollows in the rock,

which covered perhaps half of the distance down the precipice. At that

point the cliff had probably fallen away; but luckily for other purpose,

a dead tree leaned against the wall, and descending into its branches we

reached the base of the parapet, in the bed of the canon is a secondary

gulch, which required care in descending. We hung a rope or lasso over

some steep, smooth ledges, and let ourselves down by it. We left it

hanging there and used it to ascend by on our return.

Nearer approach increased our interest in the marvel.

From the south end of the ruin, which we first attained, trees hide the

northern walls, yet the view is beautiful. We remained long, and

ransacked the structure from one end to the other. According to

Richard's measurements, the space covered by the building is 425 feet

long, 80 feet high in front, and 80 feet deep in the centre. One

hundred and twenty-four rooms have been traced on the ground floor, and

a thousand people may have lived within its confines. So many walls have

fallen that it is difficult to reconstruct the building in imagination;

but the photographs show that there must have been many stories. There

are towers and circular rooms, square and rectangular enclosures; yet

all with a seeming symmetry, though in some places the walls look as if

they were put up as additions in later periods. One of the towers is

barrel-shaped; other circles are true.

The diameter of one circular room, or estufa, is

sixteen feet and six inches. There are six piers, which are well

plastered. There are five recess-holes, which appear as if constructed

for shelves. In several rooms we observed good fire places. In another

room, where the outer walls have fallen away, we found that an attempt

had been made at ornamentation: a broad band had been painted across the

wall, and above it is a peculiar decoration which shows in one of our

photographs. The lines are similar to embellishment on pottery which we

found. We observed in one place corn-cobs imbedded in the plaster in the

walls, showing that the cob is as old as that portion of the dwelling.

The cobs, as well as kernels of corn which we found, are of small size,

similar to what the Ute squaws raise now without irrigation. We found a

large stone mortar, which may have been used to grind the corn. Broken

pottery was everywhere; like specimens in the other cliff houses, it was

similar in design to that which we picked up in the valley ruins near

Wetherill's ranch, convincing us of the identity of the builders of the

two classes of ruins. We also found parts of skulls and bones, fragments

of weapons, and pieces of cloth. One nearly complete skeleton lies on a

wall waiting for some future antiquarian. The burial-place of the clan

was down under the rear of the cave.

aAppalachia, VI, 28-30, May, 1890, Boston, 1892.

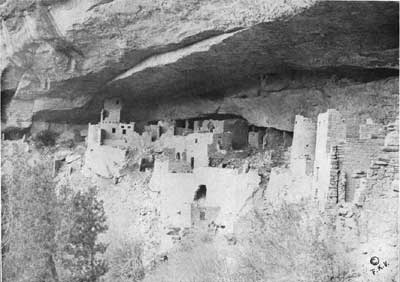

Plate 4. CENTRAL PART, BEFORE REPAIRING

(photographed by F. K. Vreeland)

|

Dr. W. R. Birdsall,a who in 1891 gave an

account of the cliff-dwellings of the canyons of the Mesa Verde, which

contains considerable information regarding these buildings, thus

refers specially to Cliff Palace:

Richard Wetherill discovered an unusually large group

of buildings which he named "The Cliff Palace," in which the ground plan

showed more than one hundred compartments, covering an area over four

hundred feet in length and eighty feet in depth in the wider portion.

Usually the buildings are continuous where the configuration of the

cliffs permitted such construction.

aJour. Amer. Geog. Soc., XXIII, no. 4, 598,

New York, 1891.

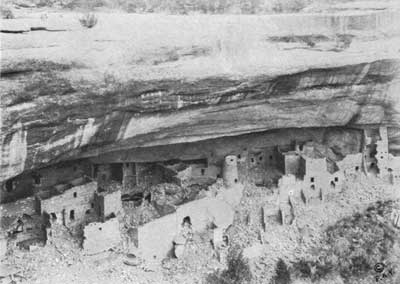

Plate 5. GENERAL VIEW OF THE RUIN, BEFORE REPAIRING

(photographed by F. K. Vreeland)

|

In the following account Baron Nordenskiöld has given

us the most exhaustive description of Cliff Palace yet

published:b

In a long, but not very deep branch of Cliff Cañon, a

wild and gloomy gorge named Cliff Palace Cañon, lies the largest of the

ruins on the Mesa Verde, the Cliff Palace. Strange and indescribable is

the impression on the traveller, when, after a long and tiring ride

through the boundless, monotonous piñon forest, he suddenly halts on the

brink of the precipice, and in the opposite cliff beholds the ruins of

the Cliff Palace, framed in the massive vault of rock above and in a bed

of sunlit cedar and piñon trees below (Pl. XII). This ruin well deserves

its name, for with its round towers and high walls rising out of the

heaps of stones deep in the mysterious twilight of the cavern, and

defying in their sheltered site the ravages of time, it resembles at a

distance an enchanted castle. It is not surprising that the Cliff Palace

so long remained undiscovered. An attempt to follow Cliff Palace Cañon

upward from Cliff Cañon meets with almost insurmountable obstacles in

the shape of huge blocks of stone which have fallen from the cliffs and

formed a barrier across the narrow water course, in most parts of the

cañon the only practicable path between the steep walls of rock. Through

the piñon forest, which renders the mesa a perfect labyrinth to the

uninitiated, chance alone can guide the explorer to the exact spot from

which a view of Cliff Palace is possible.

The descent to the ruin may be made from the mesa

either on the opposite side of the canon, or on the same a few hundred

paces north or south of the cliff-dwelling. The Cliff Palace is probably

the largest ruin of its kind known in the United States. I here give a

plan of the ruin (Pl. XI) together with a photograph thereof, taken from

the south end of the cave (Pl. XII). In the plan, which represents the

ground floor, over a hundred rooms are shown. About twenty of them are

estufas. Among the rubbish and stones in front of the ruin a few more

walls, not marked in the plan, may possibly be distinguished.

Plate XIII, as I have just mentioned, is a photograph

of the Cliff Palace from the south. To the extreme left of the plate a

number of much dilapidated walls may be seen. They correspond to rooms

1-12 in the plan. To the right of these walls lies a whole block of

rooms (13-18), several stories high and built on a huge rock which

has fallen from the roof of the cave. The outermost room (14 in the

plan; to the left in Pl. XIII) is bounded on the outside by a high wall,

the outlines of which stand off sharply from the dark background of the

cave. The wall is built in a quadrant at the edge of the rock just mentioned,

which has been carefully dressed, the wall thus forming

apparently an immediate continuation of the rock. The latter is coursed

by a fissure which also extends through the wall. This crevice must

therefore have appeared subsequent to the building operation. To the

right of this curved wall (still in Pl. XIII) lie four rooms (15-18

in the plan), and in front of them two terraces (21-22) connected

by a step. One of the rooms is surrounded by walls three stories high

and reaching up to the roof of the cave. The terraces are bounded to the

north (the left in Pl. XIII) by a rather high wall, standing apart from

the remainder of the building. Not far from the rooms just mentioned,

but a little farther back, lie two cylindrical chambers (21 a,

23). The wall of 21 a is shown in Pl. XIII with a beam resting against

it. The beam had been placed there by one of the Wetherills to assist

him in climbing to an upper ledge, where low walls, resembling the

fortress at Long House (p. 28), rise almost to the roof of the cave. The

round room 23 is joined by a wall to a long series of chambers

(26-41), which are very low, though their walls extend to the rock

above them. They probably served as storerooms. These chambers front on

a "street," on the opposite side of which lie a number of

apartmentsc (42-50), among them a remarkable estufa (44)

described at greater length below. In front of 44 lies another estufa

(51), and not far from the latter a third (52).

The "street" leads to an open space. Here lie three

estufas (54, 55, 56), partly sunk in the ground. Much lower down is

situated another estufa (57) of the same type as 44. It is surrounded by

high walls.d South of the open space lie a few large rooms

(58-61). A tower (63 in the plan; the large tower to the right in

Pl. XIII) is situated still farther south, beside a steep ledge. This

ledge, north of the tower (to the left in the plate), once formed a free

terrace (62), bounded on the outside by a low wall along the margin.

South of the tower is an estufa (76) surrounded by an open space,

southeast of which are a number of rooms (80-87). In most of them,

even in the outermost ones, the walls are in an excellent state of

preservation. The wall nearest to the talus slope is 6 metres high and

built with great care and skill.e South of these rooms and

close to the cliff lies a well-preserved estufa (88), and south of the

latter four rooms are situated, two of them (90, 92) very small. The

walls of the third (91) are very high and rise to the roof of the cave.

At one corner the walls have fallen in. This room is figured in a

subsequent chapter in order to show a painting found on one of its

walls. Near the cliff lies the last estufa (93), in an excellent state

of preservation. The rooms south of this estufa are bounded on the outer

side by a high wall rising to the rock above it. An excellent defense

was thus provided against attack in this quarter.

Two of the estufas in the Cliff Palace deviate from

the normal type. This is the only instance where I have observed estufas

differing in construction from the ordinary form described in Chapter

III. The northern estufa (44 in the plan) is the better preserved of the

two. To a height of 1 meter from the floor it is square in form (3X3 m.)

with rounded corners (see figs. 35 and 36). Above it is wider and

bounded by the walls of the surrounding rooms, a ledge (b, b) of

irregular shape being thus formed a few feet from the floor. In two of

the rounded corners on a level with this ledge (a little to the right in

fig. 36) niches or hollows (d, d; breadth 48 cm., depth 45 cm.)

have been constructed, and between them, at the middle of the south-east

wall, a narrow passage (breadth 40 cm.), open at the top. At the bottom

of one side of this passage a continuation thereof was found,

corresponding probably to the tunnel in estufas of the ordinary type. At

the north corner of the room the wall is broken by three small niches

(c, c, c) quite close together, each of them occupying a space about

equal to that left by the removal of two stones from the wall. The

sandstone blocks of which the walls are built are carefully hewn, as in

the ordinary cylindrical estufas. Whether the usual hearth, in form of a

basin, and the wall beside it, had been constructed here I was unfortunately

unable to determine, more than half of the room being filled with

rubbish. I give the name of estufas to these square rooms with rounded

corners, built as described above, because they are furnished with the

passage characteristic of the round estufas in the cliff-dwellings.

Perhaps they mark the transition to the rectangular estufa of the Moki

Indians. Besides the estufas there are some other round rooms or towers

(21 a, 23, 63), which evidently belonged to the fortifications of the

village. They differ from the estufas in the absence of the

characteristic passage and also of the six niches. Furthermore, they

often contain several stories, and in every respect but the form

resemble the rectangular rooms. The long wall just mentioned, built on a

narrow ledge above the other ruins, and visible at the top of Pl. XIII

was probably another part of the village fortifications. The ledge is

situated so near the roof of the cave that the wall, though quite low,

touches the latter, and the only way of advancing behind it is to creep

on hands and knees.

A comparison between Pl. VIII and Pl. XIII shows at

once that the inhabitants of the Cliff Palace were further advanced in

architecture than their more western kinsfolk on the Mesa Verde. The

stones are carefully dressed and often laid in regular courses; the

walls are perpendicular, sometimes leaning slightly inwards at the same

angle all round the room—this being part of the design. All the

corners form almost perfect right angles, when the surroundings have

permitted the builders to observe this rule. This remark also applies to

the doorways, the sides of which are true and even. The lintel often

consists of a large stone slab, extending right across the opening. On

closer observation we find that in the Cliff Palace we may discriminate

two slightly different methods of building. The lower walls, where the

stones are only rough-hewn and laid without order, are often surmounted

by walls of carefully dressed blocks, in regular courses. This

circumstance suggests that the cave was inhabited during two different

periods. I shall have occasion below to return to this question.

The rooms of the Cliff Palace seem to have been

better provided with light and air than the cliff-dwellings in general,

small peep-holes appearing at several places in the walls. The doorways,

as in other cliff-dwellings, are either rectangular or T-shaped. Some of

the latter are of unusual size, in one instance 1.05 m. high and 0.81 m.

broad at the top. The thickness of the walls is generally about 0.3 m.,

sometimes, in the outer walls, as much as 0.6 m. As a rule they are not

painted, but in some rooms covered with a thin coat of yellow plaster.

At the south end of the ruin lies a estufa (93) which is well-preserved

(fig. 37). This estufa is entered by a doorway in the wall, one of the

few instances where I have observed this arrangement. In most cases, as

I have already mentioned, the entrance was probably constructed in the

roof. The dimensions of this estufa were as follows : diameter 3.9 m.,

distance from the floor to the bottom of the niches 1.2 m., height of

the niches 0.9 m., breadth of the same 1.3 m., depth of the same 0.5

to 1.3 m., height of the passage at its mouth 0.75 m., breadth of the

same 0.45 m. Five small quadrangular holes or niches were scattered here

and there in the lower part of the wall.

I cannot refrain from once more laying stress on the

skill to which the walls of Cliff Palace in general bear witness, and

the stability and strength which has been supplied to them by the

careful dressing of the blocks and the chinking of the interstices with

small chips of stone. A point remarked by Jackson in his description of

the ruins of Southwestern Colorado, is that the finger marks of the

mason may still be traced in the mortar, and that those marks are so

small as to suggest that the work of building was performed by women.

This conclusion seems too hasty, for within the range of my observations

the size of the finger marks varies not a little.

Like Sprucetree House and other large ruins the Cliff

Palace contains at the back of the cave extensive open spaces where tame

turkeys were probably kept. In this part of the village three small

rooms, isolated from the rest of the building, occupy a position close

to the cliff; two of them (103, 104), built of large flat slabs of

stones, lie close together, the third (105), of unhewn sandstone (fig.

38), is situated farther north. These rooms may serve as examples of the

most primitive form of architecture among the cliff people.

In the Cliff Palace, the rooms lie on different

levels, the ground occupied by them being very rough. In several places

terraces have been constructed in order to procure a level foundation,

and here as in their other architectural labours, the cliff-dwellers

have displayed considerable skill.

One very remarkable circumstance in the Cliff Palace

is that all the pieces of timber, all the large rafters, have

disappeared. The holes where they passed into the walls may still be

seen, but throughout the great block of ruins two or three large beams

are all that remain. This is the reason why none of the rooms is

completely closed. At Sprucetree House there were a number of rooms

where the placing of the door stone in position was enough to throw the

room into perfect darkness, no little aid to the execution of

photographic work. It is difficult to explain the above state of things.

I observed the same want of timber in parts of other ruins (at Long

House for example). In several of the cliff-dwellings it appears as if

the beams had purposely been removed from the walls to be applied to

some other use. Seldom, however, have all the rafters disappeared, as

in the Cliff Palace. There are no traces of the ravages of fire. Perhaps

the inhabitants were forced, during the course of siege, to

use the timber as fuel; but in that case it is difficult to understand

how a proportionate supply of provisions and water was obtained. This

is one of the numerous circumstances which are probably connected with

the extinction or migration of the former inhabitants, but from which

our still scanty information of time cliff-dwellers cannot lift the veil

of obscurity.

bIn The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde (a

translation in English from the Swedish edition, Stockholm, 1893), (pp.

59-66), unfortunately not accessible to most readers on account of

the limited edition and the cost. For this reason the description is

here reproduced in extenso. (The references to illustrations and the

footnotes in this excerpt follow Nordenskiöld.)

cThe room marked 48 in the plan is visible in

Pl. XIII. Almost in the center of the plate, but a little to the right,

two small loopholes may be seen, and to their right a doorway, all of

which belong to room 48; the walls of 49 and 50 are much lower than

those of 48. Behind 48 the high walls of 43 may he distinguished.

dThey are shown in the plate just to the left

of the fold at its middle, rather low down.

eA part of this wall may be seen to the

extreme right of Pl. XIII, and also in fig. 34 behind and to the right

of the tower.

Plate 6. CENTRAL PART, AFTER REPAIRING

(photographed by R. G. Fuller)

|

In addition to his description Nordenskiöld gives a

ground plan of Cliff Palacea (pl. XI); a magnificent double page

view of the ruin from the west (pl. XI1I); a fine picture of

Speaker-chief's House (pl. XII); a view of the Round Tower (fig. 34); a

figure and a plan of an estufa of singular construction (T); a view of

the interior of Kiva C and of a small room at the back of the main rows

of rooms. No specimens of pottery, stone implements, and kindred

antiquities from Cliff Palace are figured by Nordenskiöld. In various

places throughout his work this author refers to Cliff Palace in a

comparative way, and in his descriptions of other ruins the student will

find more or less pertaining to it.

aThe Illustrations referred to in this

paragraph are in Nordenskiöld's work.

In his book The Cliff Dwellers and Pueblos,b

Rev. Stephen D. Peet devotes one chapter (VII) to Cliff Palace and its

surroundings, compiling and quoting from Chapin, Birdsall, and

Nordenskiöld. No new data appear in this work, and the illustrations are

copied from these authors.

bAs stated in a note (Pest, p. 133) Chapter

VII is a reprint of Doctor Birdsall's article in the Journal of the

American Geographical Society, op. cit.

Dr. Edgar L Hewettc briefly refers to Cliff

Palace as follows (p. 54):

Il suffira do décrire les traits principaux

d'un seul groupement de ruines, et nous choisirons Cliff Palace, qui en

est le spécimen he plus remarquable (pl. I b). Il est

situé dans un bras de Ruin Canyon. La vue

présentée ici est prise d'un point plus

elévé, an sud, d'ou l'on contemple les ruines d'une ville

ancienne, avec des tours rondes et carrées, des maisons, des

entrepôrts pour le grain, des habitations et des lieux de culte.

Le Cliff Palace remplit une immense caverne bien défendue et

à l'abri des rave-ages des éléments. Un sentier

conduit aux ruines. Le plan (Fig. 2) représente les restes de 105

chambres an plain-pied. On ne salt combien il y en avait dans les 3

étages supérieurs, mais il est probable que Cliff-Palace

n'abritait pas moins de 500 personnes.

Nous remarquons à Cliff-Palace de grands

progrés dans l'art de la construction. Les murs sont faits de

grés gris, taillé avec des outils de pierre, dont on volt

encore les traces. Lorsqu'on se servait de pierres irrégulieres,

les crevasses étaient remplies avec des fragments ou des

éclats de gres, puis on plâtrait les murs avec du mortier

d'adobe. On prenait de grosses poutres pour les plafonds et les

planchers, et l'on peut voir que ces poutres étaient

dégrossies avec des instruments peu tranchants.

cIn Les Communautés Anciennes dans le Désert

Américain. In this work may be found a ground plan of Cliff Palace by

Morley and Kidder, the interior of kiva Q (pl. VIII, c). and a

large view of the ruin taken from the north (pl. I, b).

(Plate and figure designations from Hewett.)

Many newspaper and magazine accounts of the Mesa

Verde ruins appeared about the time Mr. Chapin's description was

published, but the majority of these are somewhat distorted and more or

less exaggerated, often too indefinite for scientific purposes.

References to them, even if here quoted, could hardly be of great value

to the reader, as in most cases it would be impossible for him to

consult files of papers in which they occur even if the search were

worth while. Much that they record is practically a compilation from

previous descriptions.

The activity in photographing Cliff Palace has done

much to make known its existence and structure. Many excellent

photographs of the ruin have been taken, among which may be mentioned

those of Chapin, Nordenskiöld, Vreeland, Nusbaum, and others. Oil

paintings, some of which are copied from photographs, others made from the

ruin itself, adorn the walls of some of our museums. Almost every

visitor to the Mesa Verde carries with him a camera, and many good

postal cards with views of the ruin are on the market. Negatives of

Cliff Palace taken before its excavation and repair will become more

valuable as time passes, because they can no longer be duplicated. From

a study of a considerable number of these photographs it seems that

very little change has taken place in the condition of the ruin between

the time the first pictures were made and the repair work was begun.