|

PIPE SPRING

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History |

|

PART X - PIPE SPRING NATIONAL MONUMENT COMES ALIVE (continued)

Monument Administration (continued)

Geerdes and the Neighborhood Youth Program, 1968

Supervisory Historian Raymond ("Ray") Geerdes arrived with his family on April 25, 1968, to oversee the Pipe Spring National Monument. Right away, Geerdes began filing a monthly log of significant events upon his arrival. Just prior to coming to Pipe Spring, Geerdes had worked at Sitka National Historical Monument in Alaska, and earlier at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. [1912] One of Geerdes' first actions was to contact local Forest Service and BLM officials for their advice on native grass revegetation. Soil Conservation Service personnel visited in May to offer their advice. [1913] On May 18, 1968, the community of Moccasin held a picnic at the monument and extended its customary hospitality to newcomers by inviting all monument personnel. The month's culminating event was the birth of a sorrel colt to Geerdes' mare at Pipe Spring on May 27. Both horses sported Hawaiian names, Lani (the mare) and her colt, Kamehameha - surely a rarity on the Arizona Strip!

The two and one-half year period that Geerdes supervised Pipe Spring National Monument was one of great challenge and change. During this period, the plans of the Kaibab Paiute Tribe to develop a tourism complex that would provide jobs for its members posed difficult problems for Park Service administrators. Geerdes saw those problems as opportunities to forge a new relationship with the Tribe, one that would benefit both it and the Park Service, and to incorporate additional lands and cultural resources into the monument. Those events, and examples of earlier monument cooperation with the Tribe, are discussed in a later section, "Planning and Development with the Kaibab Paiute Tribe and Associated Water Issues."

Thanks to Geerdes' past experience and persistence, the summer of 1968 transformed Pipe Spring National Monument's interpretive program. If Bozarth planted the seed for the living history program, it must be said that under Geerdes it took root and sprouted, mainly due to his familiarity with government-funded youth employment programs implemented under President Johnson's "War on Poverty" policy. Geerdes had worked directly with the Neighborhood Youth Corps program for a year and one-half while at Sitka National Historical Monument where he supervised the program for the Borough of Sitka. [1914] During his first month at Pipe Spring, Geerdes contacted Fredonia High School officials to begin laying the groundwork for the monument's participation in the NYC program, traveling to NYC offices in Flagstaff and Phoenix. He also met frequently in May (and again in June) with Vernon Jake to discuss employing Paiute youths at the monument. A background on the program is provided below.

The Neighborhood Youth Conservation program was handled by a sponsoring agency, which in this case was the State of Arizona, under the federal government's Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). The State handled financing, payrolls, insurance, apportionment of openings, and dealt directly with the OEO. Youth could work up to 26 hours per week. Once the school year started, the in-school program allowed employment of about 12-16 hours per week, fitted into weekends. Under the out-of-school program (during the school year), youth could work up to 32 hours per week. [1915] Rules required that enrollees meet an income criteria, thus it favored enrollees from low-income families as well as "at risk" youth, such as high school dropouts. For its part, the recipient agency was to contribute "in-kind" services to the youth. At Pipe Spring such services included assisting with their transportation, providing work experience, remedial education, as well as guidance and counseling. In addition, Geerdes or his staff helped the youth find jobs, assisted them when they got into legal jams, and interacted with social workers and schools on their behalf. [1916] Enrollees working as guides also received instruction in Western history. Compared to other Indian tribes that ran their own NYC programs (such as the Navajo), the Kaibab Paiute obtained a program on their reservation quite late, in 1974. [1917]

Geerdes felt that relations with the Kaibab Paiute Tribe in particular would be improved by hiring some of their youth under the NYC program, and several were hired. [1918] Not all Indians hired under the program were Kaibab Paiute, however. Many were Navajo. Geerdes estimated about 30 or 40 Navajo families lived on the outskirts of Fredonia in the late 1960s. Many were impoverished and living "in wooden shacks," he reported. [1919] These families relied heavily on employment at the Fredonia lumber mill. VISTA enrollees in Fredonia played an important role in locating eligible Navajo youth and getting them enrolled in the area's NYC program. [1920]

The monument's first student enrollee, Steve Tait of Fredonia, started working weekends at Pipe Spring in early May 1968. [1921] In late May Geerdes spoke with the NYC Area Coordinator Andrew ("Andy") Sandaval in Flagstaff by phone about getting enrollees at Pipe Spring. Sandaval oversaw a five-county area, designated the Northern Arizona District Action Council in 1969. On June 11 Geerdes was informed that he would be able to get NYC workers for the monument that summer. He spoke with the program's contact in Colorado City on June 14, but by the time Park Service authorities in the regional office and Zion National Park approved his involvement with the program, enrollees there had already found other assignments. By June 14 nine enrollees were signed up to work at Pipe Spring, three girls and six boys, all from either Fredonia or Moccasin (the latter primarily from the reservation). More boys and girls were added during the summer. Enrollees worked 26 hours per week, up to 10 weeks.

Geerdes had no trouble selling Zion's Superintendent Karl T. Gilbert on the idea of employing youth under the government programs. For one thing, staff at Zion National Park already had experience using NYC workers since 1965. Formal approval from the regional office was still needed, however. When Gilbert forwarded Geerdes formal proposal to Regional Director Frank F. Kowski in late June 1968, he pointed out that

... aside from the benefits of the work projects, it is a mutual undertaking linking the National Park Service with local organizations and people. At Pipe Spring this is a much-needed public relations factor and has our approval even if only on this basis.

The planned period-costumed attendants within the fort follows recent thinking on that subject, and this experimental project will be an inexpensive method of determining its feasibility and value.

This office is giving approval to his [Geerdes'] program, which will be under our continual scrutiny as it progresses. [1922]

Kowski later congratulated Gilbert and Geerdes for proceeding with setting up the NYC program at Pipe Spring. He asked that monument staff play particular attention to visitor reaction to the costumed attendants in the fort and added, "As you know, this approach is in complete accord with the director's desire to experiment further with park attendants in period costume. Please furnish us with pictures when possible and an evaluation of the effectiveness of this part of the program so that we may send them to Washington." [1923]

Ultimately, in 1968 a total of 15 NYC enrollees was assigned to the monument over the course of the summer allowing to test out the living history program concept on a limited basis as well as to accomplish special project work. Of the 10 NYC boys enrolled that summer, four were local Paiute and five were Navajo: Russell Tom, Clarence Tom, Timothy Rogers, Gerald Jake, Corwin McFee, Johnnie Manymule, Keith Yazzie, Rex Tsi, Larry Stephenson, and Johnny Simpson. [1924] At the beginning of the summer, two white girls from Fredonia and one Paiute girl from Moccasin signed on with the NYC program: Gina Henrie and Shirla Bundy from Fredonia, descendents of "pioneer" Mormon families, with villages in southern Utah named after them (Bundyville and Henrieville); and Claudina Teller, a Paiute girl, whose family of course had even older ties to the area. Henrie and Bundy had period dresses they made at home with the help of older ladies in the community "to conform to the type of dresses worn by Mormon Pioneer young ladies of the period of the 1870s and 1880s," Geerdes later reported. [1925] It was initially planned for all three to be in period dress, but Teller could not obtain a Paiute costume as she (and Geerdes) had hoped, thus the Fredonia girls were the ones who worked in costume and escorted visitors that summer. Teller assisted in cleaning the fort and with office duties such as answering the phone, typing, and filing. (The other girls also performed these chores as time allowed.)

Claudina Teller appears to have initially preferred office work to working as a guide. Geerdes wrote that when she first came to the monument to work, while both intelligent and attractive, she was also "extremely shy, withdrawn, and introverted." During that summer, Geerdes felt she "developed poise, responsibility, and initiative." [1926] Teller mastered the Park Service filing system and took on many routine office chores. Precisely because she was Indian, monument visitors displayed a keen interest in talking to her, and gradually she grew more comfortable speaking with strangers.

At the beginning, Geerdes planned for the girls just to act as "greeters," meeting visitors at the parking lot, giving them the monument's informational leaflet, and escorting them to the visitor contact station. Then uniformed guides were to take them on the fort tour. Park Service staff, however, discovered early on that the visitors preferred to tour the fort with the costumed girls! (Those visitors who were more historically oriented or who had more in depth questions were escorted by a uniformed historian, Geerdes reported.) In addition to guide service, the girls also sometimes demonstrated how the rug loom worked. After the girls finished guiding visitors through the fort, they brought them back to the contact station where monument staff talked with them about their experience and answered questions. The costumed guides were so popular that Geerdes received permission from Sandaval to hire two more girls in early August, Helen Jensen and Patty Tait. [1927] Geerdes wanted to "break in" two more girls for the first two would not meet the age requirement to participate in the NYC program the following year. Geerdes later estimated the NYC program saved the Park Service $3,718 that year; the volunteer women from Moccasin contributed services worth at least $400.

NYC boys performed an entirely different function during the summer of 1968: hard, physical labor. All the Navajo boys assigned to Pipe Spring were from Fredonia and rode to work with seasonal guide Paul C. Heaton. Heaton interacted a great deal with the young enrollees working on the monument. [1928] The first project the boys worked on was the construction of the long-planned nature trail. (See "Nature Trail" for details on trail development.) For their next project in late July, the NYC boys began clearing a seven-acre area on the west side of the monument to prepare for seeding to native grasses. Geerdes' goal was to recreate "historic range conditions" on several areas. [1929] The general area the boys were working in, of course, was the Civilian Conservation Corps' Camp DG-44 site. The boys removed remnants of CCC-era foundations as well as brush and willows. Check dams were constructed to retard soil erosion. In less than a one-month period, the boys contributed 700 man-hours to this project. By late August the west side area was cleared and ready for disking and harrowing. By early October this area was hand-seeded with a variety of native grasses purchased by the Zion Natural History Association. [1930] "Native Grass Restoration Project I" had been completed. The savings to the Park Service by using NYC labor for the construction of fencing, corrals, and native grass restoration was estimated at $4,500. (See "Nature Trail" section for other work performed under NYC labor.)

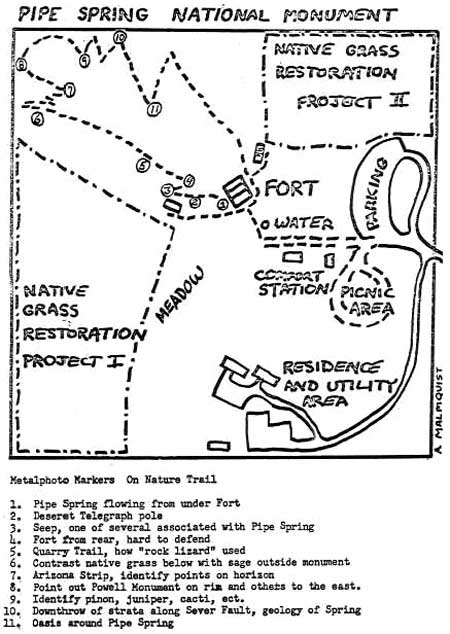

114. Map showing nature trail and native grass

restoration project areas, 1968

(Pipe Spring National Monument).

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window - ~142K)

Allen Malmquist prepared the site map shown in figure 114. The map was included in an Environmental Study Area Inventory that Geerdes submitted to Zion's Superintendent Gilbert on July 13, 1968. In addition to the nature trail, it depicts the areas originally planned for native grass restoration. (Reports of the period suggest that the NYC boys worked only on the area labeled Project I.) The numbers along the nature trail indicate sites where metalphoto markers were placed.

Geerdes held several summer picnics, which helped build camaraderie between workers at the monument and the community. The first was on June 27, to which all employees and their families were invited. A total of 60 people attended. Geerdes held another all-employees' picnic on August 19. By the time their summer appointments ended on August 24, 1968, the NYC girls had contributed a total of 1,119 hours of work; the boys had contributed 1,302 hours. [1931] Considering that six rattlesnakes were found and killed during that July and August, it's rather amazing that all the enrollees stuck around for the entire summer! [1932] In addition to the threat of snakes, on August 7, 1968, a lightning bolt struck between the visitor contact station and the east cabin near a large group of 30 visitors being escorted by NYC enrollee Gina Henrie. The work did have its hazards!

Geerdes complied with Kowski's earlier request for an evaluation of using costumed attendants in the fort in early August 1968. After two months, Geerdes judged the program as an "unqualified success." The girls giving tours, he reported, "became rapidly knowledgeable as [to] the details of the fort and the history of the area," although Geerdes does not describe precisely how they were trained (presumably they were given the monument's historical handbook for starters). [1933] While it was not originally intended for the girls to act as fort guides, due to their popularity, about 90 percent of their time was spent with visitors. Often, visitors discovered they had some family ties with the girls' families, adding to their mutual enjoyment of the tour. Visitors were "enthralled" by the girls, Geerdes wrote. He reported,

The period dress format fits in very well with the idea of a living history ranch (farm) idea. In short, these young ladies have given the old fort and our interpretation of it a living, vital dimension, pleased and benefited several thousand of our visitors, and have not involved any direct expense except the time of their training and supervision.mcm [1934]

Moreover, Geerdes added, "An unforeseen advantage in the program was the involvement of all of the NYC enrollees in the monument values and, by extension, through their parents and families to the entire Fredonia and Moccasin community." [1935] Geerdes intended to continued the NYC program in order to build on the new program. As he had predicted, it increased the monument's interaction with the Indian community of Moccasin, and Tribal Chairman Vernon Jake reportedly dropped by the monument several times a week to informally discuss business with Geerdes during this period. [1936]

In the fall of 1968, four Youth Conservation Corps program youth were hired: Bulah Hosey, Lynn Ballard, Delaine O. Cox, and Rudy Johnson. They were all terminated at various dates during November. Geerdes received permission from Sandaval to hire NYC youth during the 1968-1969 school year, and several were hired in November and December 1968, one being Fredonia high school student Heber Heaton (Mel Heaton's brother) who worked 10 hours per week at Pipe Spring as part of the NYC's in-school program. In November that year, Joe Bolander was promoted from laborer to park guide, subject to furlough. Once Bolander was converted to park guide, the monument had no permanent maintenance person on staff for the remainder of the decade. Also that fall, Zion staff Joe Davis, Keith Wilkins, and Jim Schaack visited the monument to study the fort's lighting and wiring systems. In December 1968 the monument was forced to close on Saturdays and Sundays due to government cutbacks. Geerdes reported the monument received no adverse criticism about the closure that month.

In January 1969 Geerdes met with Andy Sandaval in Flagstaff to discuss the effectiveness of the NYC program at Pipe Spring in 1968. He was promised a tentative allotment of 12 NYC enrollees for the summer of 1969. This, Geerdes later reported to Superintendent Gilbert, would allow the fort to be continuously staffed with two girls in period dress while a crew of three to five boys assisted staff with outdoor jobs. Sandaval granted Geerdes permission to employ up to six Navajo boys that winter under the out-of-school program, on the basis that Geerdes met the qualifications of a counselor. (Geerdes had formerly been both a school counselor and high school principal.) That month Geerdes hired three boys, Herman Tso, Norman Curley, and Herbert Haskie, all Navajo living in Fredonia, ages 16-21. Two other Navajo boys were hired later, but their names are not known. Timothy Rogers was hired under the NYC's out-of-school program during part of the 1968-1969 school year.

Claudina Teller also worked during the fall of 1968. Geerdes helped her get into the Phoenix Indian School for its second semester, so she left the monument at the end of 1968. She planned to return and to work at Pipe Spring during the summer of 1969, and talked of making a Paiute costume out of four deer hides before that time. In May she wrote Geerdes from Phoenix and asked if her friend Glendora Snow (then attending school in Phoenix but also from Moccasin) could work at the monument with her that summer. Geerdes replied that he would be happy to have Glendora. [1937] The two girls started working together at Pipe Spring on May 26. Once Teller completed training Snow, their schedules were split so that they usually worked together only one day a week that summer. Teller and Snow were originally supposed to work in the visitor contact station but they ended up also working as guides. [1938] Geerdes reported in early August, "The Kaibab Paiute have been included in our new interpretation with three girls in Indian dress working as guides this summer. Although the Paiute didn't play any direct role in the history of Pipe Spring, the girls are encouraged to discuss their heritage with visitors." [1939] The girls wore buckskin dresses with beads and other fringed ornaments, Geerdes later reported. [1940]

Geerdes also reported on his experience working with Navajo NYC youth at the monument:

These Navajo boys are good workers and are bilingual. One of them is a highly skilled carpenter and has made several bookcases for us and will do other carpentry work. The other boys are doing men's work in helping us finish our corrals to be used for our historic ranch branding program this summer.

We are helping these boys in many ways. We have conducted a driver's class so that they can learn the Arizona highway laws and qualify for a driver's license. We have gone to the judge for several of them when they had to appear for driving without a license.... One day a week the entire crew is sent over to the [Kaibab] Indian village to help on the Indian housing project which has fallen behind. [1941]

The increased work force that winter enabled the monument to enlarge the corral below the east cabin and to construct a fence around the meadow area at very little cost. [1942] This work expanded on the "living ranch" theme Geerdes was promoting. Work was done on the meadow-fencing project in January and was completed in February 1969. Juniper posts for both the meadow fence and corral were obtained by permit from nearby BLM lands. A half-mile of five-strand barbed wire fence was obtained by permission from Forest Service land near the Grand Canyon and reused in the meadow fence. Four sections of horizontal rails made of quaking aspen were placed on the side of the juniper post fence nearest the fort so that visitors could sit or lean on the rails "Western style" while watching or petting saddle horses kept inside the area. In late February work began on the main corral complex below the east cabin. The reconstructed corral was enlarged into a corral complex, using old corral materials donated by area ranchers. [1943] Under Mel Heaton's supervision, NYC boys (all Navajo from Fredonia) erected both the meadow fence and the corral complex. While the boys were bilingual, Heaton also spoke Navajo, having served his two-year Church mission on the Navajo Reservation.

In March 1969 Anthony G. ("Tony") Heaton of Moccasin donated an old chicken coop, in keeping with the "living ranch" goal of including more farm animals in the fort's setting. Heaton reported the coop was made from lumber taken from a blacksmith shop formerly located at Pipe Spring. [1944] In addition to chickens and the traditional pond ducks (as well as his own horses), Geerdes introduced geese into the scene in either 1969 or 1970. (At some point locals began referring jokingly to Pipe Spring as "Geerdes' Goose Ranch!") Fowl were fed the corn grown in the monument's "historic garden," and eggs from the chickens were distributed to the "poor and needy," reported Geerdes. [1945]

During part of March and April 1969, Geerdes was away from the monument attending two courses at the Mather Training Center. By the end of April, the corral complex was completed enough for the monument's first branding events, and three branding demonstrations were given on May 3, 24, and 30. [1946] It is not known who originated the idea, but these events were widely advertised. Geerdes described the program as "an unqualified success." [1947] Both white and Indian stockmen from the Moccasin area demonstrated the branding and sorting, branding their own calves. [1948] The Navajo NYC boys, all good horsemen, helped local ranchers round up the cattle and also participated in the branding event, along with Park Service employees. [1949] Geerdes described the vivid sights and smells during a demonstration and the manner in which the activity was interpreted to those watching:

The branding is for real. The blue smoke arises as hot irons touch cowhides. The piercing brawl of the branded calf, the acrid smell of burnt hair, the dust swirling in the corral, and the milling herd all testify to its reality. Explanations are given to the visitor on state laws regulating branding, the why and how of branding, the purpose of branding and dehorning, and the historical continuity at Pipe Spring back to the Winsor Castle Stock Growing Company. It has gone over big...

Yet with all its dramatic sights, smells, and sounds branding is not a sideshow at Pipe Spring. It is an integral, gut function of our living ranch. It is Living Interpretation here at its best. [1950]

The branding events were well publicized in Salt Lake City, Las Vegas, and Flagstaff newspapers. Out-of-state visitors talked about it when they returned home, prompting one call from the New England area asking when the next branding would be scheduled! The popular demonstration was held again with more than 200 attending on August 15, 1969, when David Johnson branded about 40 head of calves. On September 15 Moccasin's Bishop Owen Johnson and his two sons, David and Ronnie, demonstrated cattle branding for several hours for the benefit of 40 Albright Training Center trainees and their instructors. The branding demonstrations were another step in the direction of the "living ranch" theme Geerdes strove to put into effect at Pipe Spring.

Geerdes wanted to expand the program and also yearned for a full-time NYC supervisor to oversee the boys' project work during the summer months. He also wanted a full-time community aid to perform clerical duties in the office (he had Rosetta Teller, a Paiute girl, in mind for the latter position). The monument staff was "strained to the breaking point," he wrote program directors in Kingman and Phoenix in May 1969. He asked for their help in getting a work-crew supervisor and community aid, without which, he informed them, the interpretive program at the monument might be discontinued or curtailed. [1951] Not to cut political corners, Geerdes had already written to Senator Barry Goldwater in early April to ask for his support of Pipe Spring's NYC program. Goldwater assigned one of his staff to provide Geerdes assistance in acquiring the supervisor and park aid.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pisp/adhi/adhi10c.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006