|

PIPE SPRING

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History |

|

I: BACKGROUND (continued)

Utah and the Arizona Strip: Ethnographic and Historical Background

The Coming of the Saints and the Call to Dixie

Joseph Smith, Jr., born in Vermont on December 23, 1805, was the organizer and first president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. On June 27, 1844, Smith and his brother Hyrum were murdered by a mob at Carthage, Illinois. Brigham Young (also born in Vermont) succeeded Smith as Church president at the age of 34. Less than two years after the murders of the Smith brothers, Young and his group of followers left Nauvoo, Illinois, in February 1946, fleeing religious persecution. They headed for the Great Basin with the main party arriving at the Great Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847. [18] This region was then part of Mexico. With no official Mexican presence closer than Santa Fe and Tucson, many Latter-day Saints may have dreamed of establishing a new empire in the Great Salt Lake Valley.

The United States declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846. Its victory in the conflict and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed February 2, 1848, resulted in Mexico's relinquishment of all claims to Texas above the Rio Grande, an addition of 1.2 million square miles of territory to the United States. While this put an end to any hopes the Latter-day Saints may have had for an independent empire, they wrote a memorial to the U.S. Congress in December 1848 for creation of a territorial government. Without waiting for a response to the petition, the new immigrants undertook to create a provisional government for the "State of Deseret," electing Brigham Young, president of the Church, as their governor. On September 9, 1850, President Millard Fillmore signed a bill creating the Territory of Utah, renaming it after the Ute Indians. Young was retained as governor until 1857.

Not long after the arrival of Brigham Young and the Latter-day Saints to the Salt Lake Valley, parties of men were organized and sent out to explore other regions. [19] On November 23, 1849, one such party of 50 men set out under the leadership of Apostle Parley D. Pratt to explore southern Utah. By January 1850, Pratt's party had reconnoitered the country as far south as the mouth of the Santa Clara River, beyond the rim of the Great Basin.

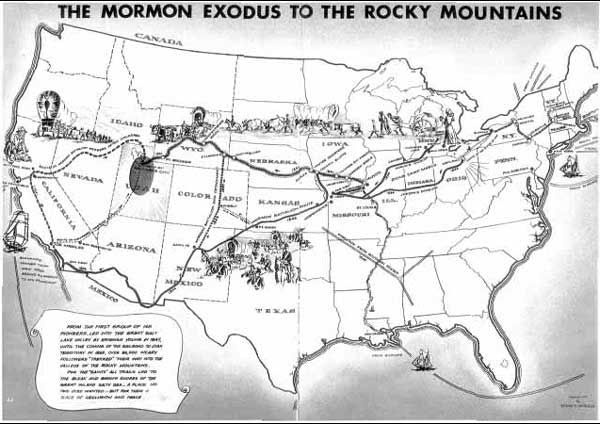

2. "The Mormon Exodus to the Rocky Mountains"

(Reprinted from Howells, The Mormon Story, A Pictorial Account of

Mormonism, 1964).

Kelly and Fowler report that slave raiding on the Southern Paiute ended soon after the arrival of the Latter-day Saints while noting that,

Initially the Mormons became unwilling participants in the trade, purchasing Indian children from the Utes who threatened to kill the children if the Mormons did not buy them. But active measures by Brigham Young and the territorial legislature ultimately ended the trade by the mid-1850s. [20]

While Mormon immigration to Salt Lake Valley went uncontested, resistance by native peoples began as soon as the colonizers headed south into the Utah Valley in 1849. The Walker War of 1853-1854 was precipitated by Mormon occupation of Ute lands. The war alerted the Church leaders that a more forceful Indian policy was needed. Five Indian missions were quickly dispatched between 1854 and 1856, all located on important trails within what were called the "outer cordon" colonies. [21]

Mormon settlers considered it their religious duty to influence the native peoples. They lived among Indians, baptized them, gave them Mormon names, and in a few cases married them. [22] By the end of 1858, only one mission survived, the Southern Indian Mission in southwestern Utah, where it served as a base for exploration, colonization, and Indian control. [23] Ironically, at the same time indigenous peoples in the Utah Territory were beginning to reel from the effects of Mormon colonization, the Latter-day Saints themselves felt their own way of life imperiled by the government of the United States. In 1856 President Brigham Young oversaw the formation of the Express and Carrying Company (also known as the Y.X. Company or the B.Y. Express Company). This business was the largest single venture undertaken to date by the Latter-day Saints in the Great Basin. It was designed to provide way stations for handcart companies and other immigration, to carry the United States mail between the Missouri Valley and Salt Lake City, and to facilitate the movement of passengers and freight between Utah and the East. In 1857 Anson Perry Winsor, an important figure in the history of Pipe Spring, was appointed to work for this company as wagon master. [24] Nearly all Mormon villages sent men to assist with the enterprise. The vast majority of them were called to work as missionaries. Their primary concern, of course, was the establishment of new settlements. [25]

On a trip to the Missouri River for Brigham Young's express company, Winsor arrived at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, on May 1, 1857. The year 1857 was marked by a serious political crisis in Utah, one that would hasten a movement of Latter-day Saints into the Arizona Strip and other areas far distant from Salt Lake City. The causes of this crisis and related events - known as the Utah War - are examined in detail in other Utah histories and will only be summarized here. [26]

In June 1857 President James Buchanan appointed a new governor for the Utah Territory. This move was designed to displace Church leaders with politicians closely tied to authority in Washington, D.C. An order directing troops to Utah was issued June 29, 1857, by the Commanding General of the Army and was justified as follows:

The community and, in part, the civil government of Utah Territory are in a state of substantial rebellion against the laws and authority of the United States. A new civil governor is about to be designated, and to be charged with the establishment and maintenance of law and order... [military action] is relied upon to insure the success of his mission. [27]

At the same time the new governor was appointed, the federal government cancelled all contracts with Brigham Young's Express and Carrying Company. Utah historian Leonard Arrington states that the activities of this company in carrying out the mail contract and in performing other economic chores for the Church figured prominently among the factors that led to the conflict with the federal government. [28] The desire of non-Mormons to impose national institutions and customs on Mormons (particularly with regard to the practice of polygamy) also played a role in the conflict.

The first of 2,500 federal troops left for Utah Territory from Fort Leavenworth under the command of Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston on July 18, 1857. The entire force committed to the expedition amounted to 5,606 men. "Express missionary" Winsor learned of the military action, known as the "Utah Expedition," while at Fort Leavenworth, and alerted Brigham Young of the impending advance of the U.S. Army. [29] Winsor sent a letter via Abraham O. Smoot who delivered the letter to Young on July 24, 1857, at Big Cottonwood Canyon, located near Brighton, Utah, about 20 miles southeast of Salt Lake City. [30] A reported 2,587 persons were gathered there that day to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Latter-day Saints' arrival in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. [31] Thus Young had many months to take defensive action against the expected arrival of federal troops. The Utah Territorial Militia — consisting of about 3,000 men - was mustered into full-time service. While they were instructed to "take no life," the militia considerably slowed the advance of troops through implementation of a "scorched earth" policy, destroying resources ahead of the Army's advance. [32]

The advance of federal troops on Utah was considered a threat and Utah Mormons considered it continuing "gentile" persecution. [33] While the troops were still en route, a tragic event occurred in southern Utah. On September 11, 1857, Mormon militiamen killed over 100 men, women, and children who were part of a group of Missouri and Arkansas emigrants; the incident is known as the "Mountain Meadows massacre." While the massacre involved many individuals, John Doyle Lee was the only person brought to trial much later. An all-Mormon jury found him guilty and sentenced him to death, a sentence carried out on March 23, 1877. [34]

On September 15, 1857, Brigham Young declared martial law and proclaimed, "Citizens of Utah - We are invaded by a hostile force." Federal troops, in fact, were still en route. As he made preparations to defend the Kingdom, Young ordered Latter-day Saints in Idaho, Nevada, California, and other western states to abandon their settlements to "come home to Zion." The same directive was issued to missionaries scattered throughout the world, resulting in the return of several hundred. [35] Anson P. Winsor was later sent to Echo Canyon, east of Salt Lake City, in October 1857 to make fortifications and to guard the area against federal troops. In the spring of 1858, Winsor was called back to Echo Canyon with 300 men to relieve troops who had been on duty there the previous winter. Outright war was averted when negotiations held in February and March 1858 led to an agreement that Brigham Young would relinquish his governorship of the Utah Territory. Alfred Cumming, a federal appointee from Georgia who had served as Superintendent of Indian Affairs on the Upper Missouri, arrived to take over the territorial government on April 12, 1858.

The military actions of the federal government and its subsequent takeover of official government functions by "gentiles" reinforced the Latter-day Saints' long standing sense of injustice and oppression. [36] Just prior to Cumming's arrival, Brigham Young called a "Council of War" in Salt Lake City on March 18, 1858, where he announced his plan "to go into the desert and not war with the people [of the United States], but let them destroy themselves." Four days later, Young wrote, "We are now preparing to remove our men, women, and children to the deserts and mountains..." What followed has been called "The Move South." The events that follow chronicle this southern migration as it pertains to the Arizona Strip region near Pipe Spring.

Brigham Young instructed missionary and explorer Jacob Hamblin to learn something of the character and condition of the "Moquis" (whom we now refer to as the Hopi) and to preach to them. On October 28, 1858, Hamblin and a small party of men were sent southeast from the young southern Utah settlement of Santa Clara to contact the Hopi. [37] A Kaibab Paiute referred to as Chief Naraguts served as the party's guide through the region. Their other purpose was to determine if the Latter-day Saints could retreat to this region should the conflict with the U.S. Army become unbearable, to establish a mission among the Tribe, and to explore the region. [38] On October 30, 1858, the men encamped at Pipe Spring. Hamblin's party is the first documented visit by Euroamericans to Pipe Spring. Their explorations revealed the general topography between the Virgin and Colorado rivers to other Euroamericans, opening the way for later colonization of northwestern Arizona. The name "Pipe Spring" was in use by the time a second Hamblin mission to the Hopi passed by Pipe Spring on October 18, 1859.

Protected by the Utah Territorial Militia (also known as the Nauvoo Legion), Mormon expansion moved quickly, occupying the richest river valleys, reducing game, and pre-empting forage and water holes. Serious friction continued between Indians and settlers as whites penetrated other areas of Utah. [39] Between 1858 and 1868, 150 new towns were founded, and the 1850 Utah population of 11,000 grew to 86,000 by 1870. [40]

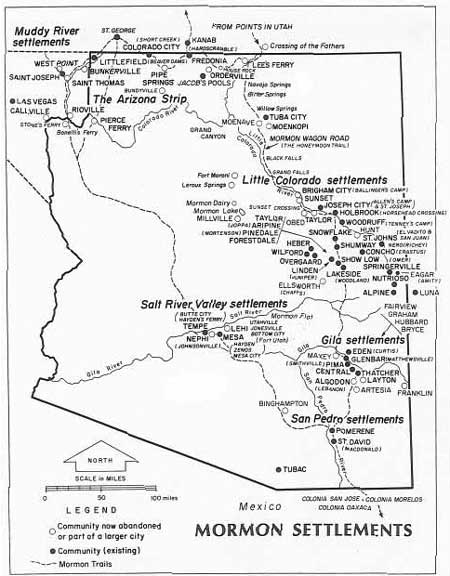

3. Erastus Snow, in charge of Arizona colonization (Reprinted from McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona, 1921). |

A move to relocate the Ute on the Uintah Reservation in the 1860s led to the Black Hawk Indian War of 1865-1868. [41] Initial fighting broke out between the Ute and the Latter-day Saints in 1865 in the Sevier Valley in central Utah. The war led the Church in 1867 to build Cove Creek Fort 200 miles south of Salt Lake City, located midway along the 60-mile stretch between Fillmore and Beaver. The fort's primary purpose was to protect the telegraph line that linked the area's settlements to Salt Lake City. [42] The Utah Territory's last major Indian conflict, the war forced the temporary abandonment of a number of southern settlements. Ute resistance was contagious, stirring some Southern Paiute into sporadic resistance. [43] However, no major confrontations took place between the Latter-day Saints and Southern Paiute. Some ascribe the non-combativeness of the Southern Paiute to activities of missionaries among them, most notably, Jacob Hamblin. [44] Perhaps, more likely, they simply lacked the numbers and resources with which to effectively stave off intruders, whether Euroamerican or Indian, such as the Ute and Navajo. [45]

The early 1860s mark the beginning of Mormon encroachment on Kaibab Paiute territory through the establishment of missions and permanent white settlements. At a semi-annual general conference of the Church held in October 1861, Brigham Young called 300 families to the Dixie Mission. [46] Utah's "Dixie" was in the Virgin River Basin, established to produce cotton, molasses, wine, and other warm-climate crops. On November 29, 1861, a group headed by George A. Smith and Erastus Snow left Salt Lake City to colonize the valleys of the Virgin and Santa Clara rivers. The town of St. George was surveyed and incorporated in 1861. Again on October 19, 1862, Young issued another call for 250 families to go south. Two other important events occurred earlier that year which would eventually spur colonization activity in southern Utah and northern Arizona, along with other western regions: passage of the Homestead Act on May 20, 1862, and President Abraham Lincoln's signing of the Pacific Railroad Act on July 1, 1862. The latter act authorized and provided financial aid for the nation's first transcontinental railroad. While the Civil War delayed its construction, the union of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, ended the isolation of Brigham Young's Kingdom. Young organized a company to build a trunk line between Salt Lake City and Ogden, completed on January 10, 1870. The railroads provided a transportation corridor that linked Utah commercially to other states while ensuring a continuing stream of new immigrants. The Homestead Act, on the other hand, added an incentive to land-hungry settlers to take their families into arid lands that would have otherwise been considered desolate and unpromising by most folks back east. Not until 1869 did federal officials open a land office in the Utah Territory. Prior to that time, Church officers supervised settlement and land distribution, issuing land certificates to settlers in both Utah and the Arizona Strip. [47]

4. Mormon settlements along the Arizona Strip and

in Arizona

(Reprinted, by permission, from Walker and

Bufkin, Historical Atlas of Arizona, copyright © 1979 by the

University of Oklahoma Press).

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window - ~125K)

Other events had more immediate effects on settlements. Kit Carson's 1863-1864 bloody campaign against the Mescalero Apache and Navajo in the Territory of Arizona (which at that time included New Mexico) resulted in the infamous "Long Walk" during the winter of 1863-1864 and subsequent incarceration by April 1864 of about 9,000 Navajo and 400 Mescalero Apache at Fort Sumner in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico Territory. Many there suffered from disease, inadequate food rations, and crop failures. Before being released to return to their homelands in 1868, 1,000 Navajo died at Bosque Redondo. [48]

White settlers in Arizona and New Mexico hoped that the creation of reservations in the 1860s would solve the "Indian problem" and end their war with the Apache and Navajo. For Indians, of course, white immigrants and their protectors, the territorial militias, and the U.S. Army created the problem. Pockets of Indian resistance to white encroachment persisted for decades in some cases. [49] Displaced by years of conflict with the U.S. Army and refusing to go to their assigned reservation, some Navajo took refuge in Monument Valley and other remote locations while continuing to raid villages and livestock in southwestern Utah and along the Arizona Strip. [50]

Manuelito was the last of the Navajo war chiefs who held out against forced incarceration, hiding with a small band of about 100 men, women, and children along the Little Colorado. Finally, he and 23 defeated and emaciated warriors surrendered at Fort Wingate on September 1, 1866. [51] The free Navajo not only lived in fear of capture or death by U.S. Army soldiers, but also of Ute and Mexican slave raiders who still trafficked in stolen children. The choice between going to the reservation and remaining free was difficult, with either alternative posing considerable threats to survival. Some resistance leaders finally chose to surrender, concluding a treaty with U.S. government representatives led by General William Tecumseh Sherman at Bosque Redondo in May 1868. The 1868 treaty did not end hostilities along the Arizona Strip, however. Navajo raids continued to be a problem, particularly during the winters of 1867-1870. During the 1860s, the Latter-day Saints in Kanab Creek area permitted some Paiute Indians to have access to water and land for farming. In turn, these Paiute warned members of the fledgling white communities of impending raids by the Navajo, who were also the traditional enemy of the Paiute. [52] Since both Latter-day Saints and Paiute were vulnerable to the Navajo attacks, they served for a time as mutual allies.

In September 1870 Jacob Hamblin, accompanied by Major John Wesley Powell, concluded a peace treaty on behalf of the church with the Shivwits Paiute at Mt. Trumbull, on the north side of the Colorado River. (Powell was an explorer and geologist who convinced the Smithsonian Institute and Congress to fund two exploratory expeditions he led down the canyons of the Colorado and Green rivers during 1869 and 1871-1872. He conducted other explorations in Arizona and Utah in 1874 and 1875. Powell became director of the Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region in 1875, director of the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1879, and director of the U.S. Geological Survey in 1881. [53] ) Soon after, Hamblin and Powell embarked to Fort Defiance, New Mexico Territory, on a peace mission. At the time 6,000 Navajo were gathered there to receive their annual government allotments. Their meeting with the Tribal Council, begun on November 1, concluded on November 5 with a peaceful settlement. One source reports that Hamblin wrote Erastus Snow details of the meeting in a letter dated November 21, 1870. [54] Another source states that Hamblin returned to Kanab with word of the treaty about December 11, 1870. [55] The raids on white settlements soon ended, allowing the development of existing towns and the establishment of new ones.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pisp/adhi/adhi1c.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006