|

PIPE SPRING

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History |

|

I: BACKGROUND (continued)

Utah and the Arizona Strip: Ethnographic and Historical Background

Moccasin Ranch and Spring

Because the settlement of Moccasin, its residents, and the main spring there are so closely tied to the history of Pipe Spring (as well as to the Kaibab Indian Reservation), a brief history of Moccasin is included here.

The Mormon settlement of Moccasin is located four miles north of Pipe Spring, just a few miles south of the Utah line. Histories of Moccasin vary in detail, particularly with regard to its earliest years. The following is an account by historian James H. McClintock:

The place got its name from moccasin tracks in the sand. [203] The site was occupied some time before 1864 by Wm. B. Maxwell, but was vacated in 1866 on account of Indian troubles. In the spring of 1870, Levi Stewart and others stopped there with a considerable company, breaking land, but moved on to found Kanab, north of the line. This same company also made some improvements around Pipe Spring. About a year later [1871], a company under Lewis Allen, mainly from the Muddy, located temporarily at Pipe Springs and Moccasin. To some extent there was a claim upon the two localities by the United Order or certain of its members. The place was mainly a missionary settlement... [204]

Historian C. Gregory Crampton wrote that Maxwell established his claim at Moccasin at "about the same time" that Whitmore acquired Pipe Spring. [205] As mentioned earlier, Maxwell also owned a ranch at Short Creek, 25 miles west of Pipe Spring, where he lived. According to Crampton, Maxwell sold the Moccasin claim in 1864 to one Rhodes, who moved to the spot with Randall and Woodruff Alexander (and possibly others). [206] As mentioned in the section pertaining to the organization of the Winsor Castle Stock Growing Company, sometime between 1870 and 1872 the Church negotiated the purchase of one-third interest in Moccasin Spring. This interest was transferred to the Winsor Company soon after organization in January 1873. While the water at Moccasin Spring may have provided water for the Church herds, it also served an additional purpose. As cited earlier, it was noted at the Winsor Company's organizational meeting that "Some 15 acres of land have been irrigated by the one-third interest in Moccasin Springs." In August 1869, John R. Young had reported four tons of hay being harvested "on the Moccasin spring creek" just 2.5 miles north of Pipe Spring. It appears that prior to 1870 either Maxwell or the second owner(s) of Moccasin Ranch was irrigating land with water from Moccasin Spring to produce winter feed for livestock. It is obvious then why the Church had a strong interest in purchasing one-third interest in Moccasin Spring.

12. William B. Maxwell, first Mormon claimant of Moccasin, undated (Reprinted from McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona, 1921). |

In later years some conflict would emerge in the historical record over the question of when the Kaibab Paiute began to live at Moccasin Spring, so it is helpful to note some of the recorded memories of the early white settlers. [207] Emma Seegmiller (1868-1954), mentioned earlier, was one of the women who hid at Pipe Spring during the "Raid" of the late 1880s. She wrote, "Since my earliest recollection, Moccasin Springs, or near vicinity, has been the home of a tribe of Ute [sic] Indians, and for many years an Indian reservation has adjoined the Moccasin Ranch property." [208] While the federal government did not withdraw land in the area for Indian use until 1907, her "earliest recollections" would most likely date to the 1870s. Emma Seegmiller also recalled good relations between the Paiute and local Latter-day Saints, including melon feasts, the two groups joining together for dances, and the Indians praying for Church and U.S. leaders, such as George Washington. [209]

Emma Seegmiller is not the only person who recalled the Paiute living at Moccasin Spring from an early date. Silas Smith Young, born in 1863 and the son of John R. Young, later told Edwin D. Woolley, Jr., that Indians were living at Moccasin when he was there, and that it was not yet claimed by white men. [210] The boy, who would have been only seven or eight years old at the time, was probably unaware of William B. Maxwell's 1865 claim. As Maxwell's primary ranch was in Short Creek, he may have spent little time at the Moccasin claim. What is most important to note about the memories of Emma Seegmiller and Silas Smith Young is that their record is the earliest available Euroamerican acknowledgment of native people living in the immediate area at least by the time of the fort's construction in 1870.

To return to the chronology of ownership of the Moccasin ranch, according to Leonard Heaton, Christon Hanson Larson purchased the Moccasin property in 1874. Larson owned the ranch for two years. Heaton reported that Larson then sold it to Lewis Allen and Willis Webb, along with two-thirds of the water rights from Moccasin Spring. Canaan Cooperative Cattle Company Cattle Company owned the other one-third of water. (Brigham Young and the Church controlled this company, like the Winsor Company, thus the Church was still preserving its one-third rights through the Canaan Company.) Heaton wrote that on March 4, 1887, Allen and Webb joined the United Order at Orderville and turned over to the Order their land and rights to two-thirds flow of the spring. [211] Emma Seegmiller gives a slightly different account, writing that Lewis Allen (also known as "Moccasin Allen") acquired Moccasin Ranch as a result of his joining the United Order. Like James H. McClintock, she makes no mention of Willis Webb. [212]

John R. Young, nephew to Brigham Young, organized the United Order at Mt. Carmel, Utah, on March 20, 1874. It was a communitarian effort that emerged after the economic Panic of 1873. Promoted by Brigham Young, the program was designed to spur spiritual and communal economic revival and, for a time, was particularly successful in southern Utah. The town of Orderville, located two miles north of Mt. Carmel, was surveyed on February 20, 1875. It was situated on the Virgin River in Long Valley, in southern Utah. The heyday of the Order was 1880 when its adherents numbered nearly 600. Farming lands were expanded to include areas scattered through Long Valley and Kanab. [213] By 1881 the Orderville Order "owned 5,000 head of sheep and the cattle had increased ten-fold." [214] Such success led the Church to put this Order in charge of the Pipe Spring ranch in 1884. [215] Leonard Heaton reported in 1961 that his great-grandfathers were among the early settlers who had moved to Long Valley in 1870, after having spent five years on the Muddy River in Nevada trying to raise cotton and to "be peace makers among the Indians along the California road." [216] The Heaton family was thus a part of the Orderville communitarian experiment from beginning to dissolution.

Either in late 1879 or early 1880, the Church "bought" the water rights to one-third of the flow of Moccasin Spring from the Canaan Company (which the Church controlled) and established an Indian mission at Moccasin Ranch for the Kaibab Paiute. [217] It has been reported that at this time the Church gave the one-third water rights of the spring to the Kaibab Paiute. In February 1880, the Orderville United Order sent C. B. Heaton to oversee the Indians at the mission. The Kaibab Paiute are reported to have numbered 150 at the time the mission was established. During this period of Moccasin's history, sorghum, fruits, and grapes were cultivated. The site was particularly well known for its sorghum and melons. Leonard Heaton later reported, "It was when the United Order was in operation that the Paiute Indians were first introduced [sic] to take up farming, as the Mormon Church gave the Indians one-third of the spring and 10 acres of land and had the foreman of the ranch teach them the arts of farming." [218] The gift of land and one-third rights to the spring to the Paiute would have accomplished a number of Church objectives, as mentioned earlier.

When the federal government began intensive prosecutions of polygamists in 1885, Church authorities counseled dissolution of the United Order. Sources report a wide variety of dates for the dissolution of the Orderville Order. One states that the United Order of Orderville began in 1875 and was practiced for 11 years, suggesting dissolution in 1886. [219] Leonard Heaton also reported that the Order dissolved in the 1880s. [220] Angus Woodbury wrote that the dissolution was gradual, hastening after 1885. (According to Woodbury, the United Order of Orderville did not officially dissolve until 1900. By that date, however, the only property it held was a woolen mill. [221] ) Prior to then, the Order sold its farm lands, livestock, ranches, tannery, and sawmill to members, with each man allowed to use his work credits to buy property. Common possessions of all were distributed among the 100 or more families that remained. [222] Five Heaton brothers, all members of the Order, had been working at the Moccasin ranch for a year or so, and received the 400-acre property as their share of the common property in 1893. [223] One of the brothers, Jonathan Heaton, later bought out his brothers' interest in the property. [224] It was Jonathan Heaton and his plural wife Lucy who would sire the population of the village of Moccasin in the first three decades of the 20th century, including son Charles C. Heaton, father of C. Leonard Heaton, future custodian of Pipe Spring National Monument. [225]

A school building was constructed in Moccasin in 1904-1905. The building was used for Church services on Sundays by special permission of the school board. For a time, the Kaibab Paiute continued to farm the small piece of land given to them by the Church and to live in the community of Moccasin. As late as 1908, when the Indian camp was relocated 1.5 miles to the southeast, Leonard Heaton could remember the Kaibab Paiute using tepees as homes and moving from Moccasin to the mountains in the summer. They returned in the winter, he stated, "...leaving the white men to care for their crops while they were gone during the summer, coming home with their horses loaded with dried venison and pine nuts which they would trade for fruits and vegetables and flour." [226] While Buckskin Mountain at the northern part of the Kaibab Plateau was the closest, some Kaibab Paiute regularly made their summer hunting and gathering excursions to other areas on the Kaibab Plateau. Heaton wrote that another name used to refer to the Kaibab Paiute was the "... Moccasin Indians, a name applied to the Indians by the Mormon people who tried to get them to settle down at Moccasin, Arizona, four miles north of the monument, and live like white people, farming and cattle raising, instead of roaming over the country in search of a living." [227]

By 1921 the white population of Moccasin was 39, made up of 14 adults and 25 children. Sugar cane, corn, alfalfa, and potatoes were grown on the acreage that was cultivated. Possibly as much as 150 to 200 acres were irrigated with water supplied by Moccasin Spring, which its residents claimed had been "highly improved by white settlers." [228] Five hundred head of cattle were grazed in the area, 100 year-round and the rest during the winter months. The patriarch of the family, Jonathan Heaton, died in 1928 at age 72 from injuries sustained in a farm accident. [229]

13. Kaibab Paiute Indians at Moccasin, 1904. From

left to right: Charles Bulletts and Toby John, on horses; Minnie

(Soxoru) Tom, wife of Indian Tom; Mammie (Wuri) Frank, her child Maroni,

and her husband Mustach Frank; Young Williams (Na'apiv), Dave Cannon;

Indian Tom (Naap) and son, Tommie Tom (Oaisin), Tappio Dick; Annie

(Wiuys) Frank; Tunanita'a (John Seamon's father); Adam Commadore, his

wife Fannie (Punuv) Commadore and their two grandchildren

(Photograph by Charles C. Heaton, Pipe Spring National Monument, neg.

2476).

During the early 1920s, residents of Moccasin rallied to defend their rights to settled lands that lay within the bounds of the Kaibab Indian Reservation. Local residents and their attorneys described the early Kaibab Paiute as "roving bands of Indians who had no permanent place of abode," who only settled down once they were given the "care and attention of the white settlers." [230] (The story that the Paiute never lived in the area until the establishment of the Church mission there is contradictory to reports by other sources, cited earlier.) The Kaibab Paiute had long utilized the resources most valued by settlers, land and water, as well as native plants and animals. Perhaps because their use was dictated by a seasonal, semi-nomadic tradition, or perhaps out of pure self-interest, some white settlers chose to deny any prior use or rights of Indians to these resources, particularly after the lands were withdrawn from settlement for Indian use.

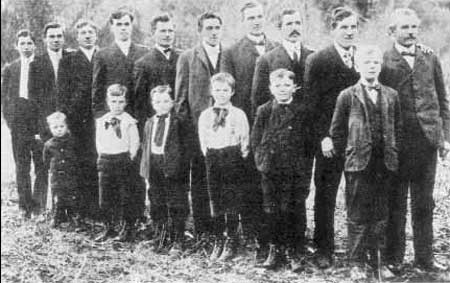

14. Jonathan Heaton and his 15 sons, Moccasin, 1907

(Reprinted from McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona,

1921).

By the early 1940s, Moccasin's white population totaled 63, all reportedly descendants (by birth or by marriage) of Jonathan and Lucy Heaton and their 11 children. As the children grew up and married, they were allotted a share of the land. [231] A small store was located in Moccasin, patronized mostly by the Kaibab Paiute living on the reservation. In 1928 it was agreed among the Heaton family that none of the land would be sold to an outsider. A problem arose when, during the 1941 restoration of the fort at Pipe Spring, men needed to be hired as laborers. Custodian Leonard Heaton hired 40 men, who all listed their address as Moccasin. When the payroll was submitted to the chief clerk of Southwestern National Monuments, a few eyebrows must have been raised. Of the 40 men listed, the last names of 37 were "Heaton." (The other names, Brown and Johnson, were related to the Heatons by marriage.) [232] Federal rules against employing relatives appear to have been ignored in Pipe Spring National Monument's early years, perhaps because the Heatons of Moccasin supplied such a close and capable labor pool.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

pisp/adhi/adhi1g.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006