|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 2:

SITE HISTORY (continued)

Central Pacific and Union Pacific Labor Forces

Hiring a sufficient labor force posed a serious problem for the Central Pacific as most men could easily earn higher wages by working the relatively nearby mines. When the company did manage to assemble the necessary crews, company officials were always in fear of the men going on strike in an effort to obtain yet higher wages. Utley notes that in an effort to break a strike, Charles Crocker sent for some Chinese workers. Pleased with how hard they worked and the quality of their workmanship, the Big Four were soon sending ships to China for recruits. By 1865 there were 7,000 Chinese employed in construction of the Pacific Railroad. By 1868, this number had grown to 11,000 (Utley 1960:25). Leland Stanford described the Chinese workers as "quiet, peaceable, industrious, economical — ready and apt to learn all the different kinds of work required in railroad building" (Saxton 1966:144).

The Chinese were organized in work groups or gangs of about 12 to 20 each. Each group had a head man, usually someone with a fairly strong command of English, who at the end of each work day negotiated with a foreman to record how much time the gang had worked; this head man then kept track of how the time broke down per worker to ensure that each was correctly paid. He was also responsible for buying provisions for the gang because the Chinese workers, unlike other laborers on both lines, were expected to pay for their own food out of their wages.

Each gang also had its own cook who prepared meals and kept water hot so that each worker could wash off the day's labor with a hot sponge bath at the end of the day. The evening meal differed greatly from those of the other Central Pacific laborers and from those of the Union Pacific workers who basically stuck to meat, beans, potatoes and bread. In contrast, the Chinese feasted on dried oysters, dried abalone and other dried fish, dried bamboo shoots, salted cabbage, dried mushrooms, vermicelli, dried seaweed, dried fruit, rice, pork and poultry. The Chinese drank tea, which — because the water had been boiled — had the distinct advantage of preventing the intestinal distress that other workers suffered when they drank cold water of varying degrees of purity (Chinn 1969:43-48).

Also in stark contrast to Union Pacific workers, the Chinese did not drink any alcoholic beverages. Thus, the Central Pacific never had to contend with any "blue Mondays" on their account. Neither Central Pacific's superintendent of construction, James Strobridge, nor Leland Stanford would abide drinking in the Central Pacific construction camps. Strobridge in fact would routinely send someone to destroy the tent of anyone who had set up shop to sell whiskey along the Central Pacific construction line (Anderson 1974:17-18; Galloway 1950:162). Workers on the Union Pacific, on the other hand, were notorious for their consumption of alcohol. As Bernice Gibbs Anderson succinctly put it, the "Union Pacific was built on whiskey" (Anderson 1974:18).

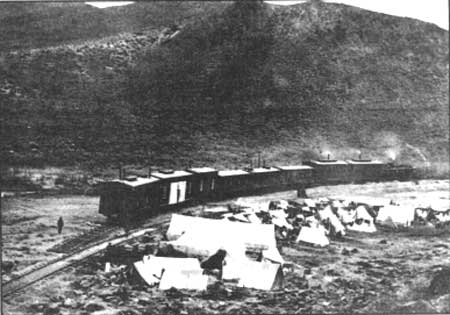

The Central Pacific work week was six days long; the workday stretched from sunrise to sunset. As the race approached Promontory, the workers even continued working past sundown, working by the light created by burning sagebrush. Initially the Chinese workers' wage was set at one dollar per day, or $26 a month. Later this was increased to $35 per month. After subtracting expenses, most or them netted between $20 and $30 for each month of work. On Sunday, the Chinese laborers typically washed and mended their blue smocks and other clothes. For living quarters, the Central Pacific issued low cloth tents but many Chinese preferred instead to live in dugouts (Chinn 1969:43-48; Kraus 1969a:53-54) [Figure 2]. The Chinese largely kept to themselves, apart from the other Central Pacific employees. These included Irish and Cornish workers, in addition to Paiute and Washo Indians who were employed to build the line in Nevada (Kraus 1969a:51-52).

|

| Figure 2. Chinese construction camp at end-of-track, eastbound construction train just west of Powder Bluff, Nevada. Source: Alfred Hart photo No. 327, 1868-69, Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha Nebraska. |

The Caucasian workers on the Central Pacific ate their meals at dining facilities on the camp train. This train provided living quarters for Strobridge and his wife, described by an Alta California correspondent as a "home that would not discredit San Francisco." It also included a store, a kitchen, sleeping quarters and a telegraph office (Kraus 1969b:216-217).

With the Union Pacific waiting until the close of the Civil War to actively begin work on the construction of the railroad, finding a ready and able labor pool was not a problem. Utley (1960:25) notes that "veterans of the Union armies, mostly Irish immigrants, flocked to Omaha to enlist in Casement's grading and track gangs." In addition to Irish laborers, the Union Pacific hired Germans, Englishmen, American Indians, and a 300-man force of freed Blacks (McCague 1964:117).

The numbers of Union Pacific laborers grew from some 250 when construction out of Omaha began to roughly 10,000 near Promontory. Only about one fourth of the total worked as track-layers. Other positions included bakers, cooks, herdsmen, blacksmiths, teamsters, carpenters, bridge-builders, masons and clerks. Averaging $3 a day, they earned more and worked fewer hours than their Chinese counterparts. Also in contrast to the Chinese, they tended to bathe if and when a stream was nearby (Combs 1986:630). Still attired in portions of their old Civil War uniforms, the Union Pacific workers were known for their hard-drinking and rowdy ways.

Somewhat similar to the Central Pacific's camp train, at the end of the UP track, four "house cars" — each twice the length of a regular boxcar, formed the camp's headquarters. One car served as kitchen and dining room. Another functioned completely as a large dining hall. A third was divided in half, providing both dining and sleeping facilities while the fourth was wholly used for sleeping in 3-tiered bunk beds on both sides of the car. The camp literally functioned as a "town on wheels" (McCague 1964:118). Other boxcars contained all sorts of supplies. The end of-track camp train also carried a car for storing beef as cattle were butchered from among the herd of some 500 that followed the train. Two cars together served as a bakery while another carried grain for the horses and mules. The camps for the graders were much simpler, less accommodating affairs: these workers either built dugouts or lived in tents that were pitched closely together in orderly rows both for convenience and as protection against hostile Indian attacks. If the camp were a big one, a temporary shack was sometimes built to provide space for an office, kitchen and storage. Like the work day on the Central Pacific, work for graders, track layers, and everyone else began at dawn and concluded at sunset (McCague 1964:118-120).

The editor of the Baltimore American described the Union Pacific work force by noting its semi-military system of organization:

Nine out of every ten men who are now working on the line of this railroad have been in the army, and from there have brought the habits of discipline, the temper of hardy reliance and the love of an adventurous open air life which has made them the best railroad builders in the world. One can see all along the line of the now completed road the evidences of ingenious self-protection and defence (sic) which our men learned during the war. The same curious huts and underground dwellings which were a common sight along our army lines then, may now be seen burrowed into the sides of hills or built up with ready adaptability in sheltered spots. The whole organization of the force engaged in the construction of the road is, in fact, semi-military. The men who go ahead, locating the road, are the advanced guard. Following these is the second line, cutting through the gorges, grading the road and building bridges. Then comes the main line of the army, placing the sleepers, laying the track, spiking down the rails, perfecting the alignment, ballasting the rail, and dressing up and completing the road for immediate use [Union Pacific 1868:8-9].

Nearly a century later, railroad historian James McCague also likened the Union Pacific's work crews to an army: "Like an army in itself— hard-bitten, sinewy, honed to rawhide resilience, profane, brawling, alcoholic and altogether unstoppable — the work force moved westward... .In a very real sense, in fact, these Union Pacific men were an army, with Major General Grenville Dodge at the top and the likes of Brigadier General Jack Casement for corps commanders." More than this, however, the work gangs were welded together "with the glue of military training and elan. The five-year War Between the States had left in these men a sturdy sense of organization and discipline, and leaders like Dodge and Casement knew how to use it to the fullest" (McCague 1964:126, emphasis in original).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr2b.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003