|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 2:

SITE HISTORY (continued)

Development and Completion of the Transcontinental Railroad: 1868-1869

By spring of 1868, both companies had progressed to the point where they needed to determine the best route through northern Utah. The debate focused on whether a route north of the Great Salt Lake that bypassed Salt Lake City altogether was preferable to one that passed through the city and then went south of the lake. The race to complete the railroad and the competition for the greater federal subsidy was still proceeding in earnest: Central Pacific surveyors were locating a line as far east as Fort Bridger, Wyoming, while Union Pacific surveyors had already staked a line to the Nevada-California border. The decision concerning the best route around the Great Salt Lake would influence, in turn, where the two lines would finally meet.

The Union Pacific's initial surveys in the Utah area had been conducted as early as 1864 by Samuel Reed. The proposed route through Salt Lake City ran either south of the Great Salt Lake or across it, although crossing it was ultimately considered technologically unfeasible at this point in time (Galloway 1950:135; McCague 1964:288; Reeder 1970:23; Strack 1997:47). By 1867 the Central Pacific had covered the area in a survey conducted by Butler Ives; he apparently looked at routes to both the north and south of the lake, although the preferred route in his view was the northern one, which was less plagued by the mudflats and sinkholes that characterized the southern route (Bain 1999:364).

The Union Pacific's Chief Engineer Grenville Dodge, for his part, also ordered a survey of the area north of the lake. For several months the surveyors and engineers sought to find a route that would either pass around the lake or across it and avoid the steep climb over the Promontory Mountains. During the summer of 1868, Union Pacific surveyor F. C. Hodges was called into the field and

dispatched to Promontory Point, on the west side of Bear River Bay, with instructions to explore the country thence westward to Humboldt Wells. His survey was commenced at Promontory Point on the 12th day of June [1868] and completed to the initial point of Bates and Reed, at Humboldt Wells, a distance of one hundred and ninety-eight miles on the seventeenth day of July [J. Blickensderfer, Jr., to G. M. Dodge, letter, Jan. 26, 1869, printed in Report of the Chief Engineer of the Union Pacific Railroad, February 11, 1870, 41st Congress, 2d session, House Executive Document 132:41 (Report of Chief Engineer)].

Another Union Pacific surveyor, James R. Maxwell, began a new line along the north side of Weber River through Ogden, around the north end of Bear River Bay, over the summit at Promontory, to finally connect with Hodges' line. Jacob Blickensderfer, who as engineer of the Utah Division, was in charge of locating the Union Pacific line west of Green River, explained that this line was almost the same as one that was first surveyed in 1867 by the Central Pacific surveyor, Butler Ives. It varied slightly from Ives' survey, especially on the west slope (Blickensderfer to Dodge, letter, Jan. 26, 1869, printed in Report of Chief Engineer 1870:41). Blickensderfer further explained:

Having by the end of July completed the location between Green River and Salt Lake Valley, and obtained a connected preliminary line from mouth of Weber Canon to Humboldt Wells, all the forces at my disposal were concentrated on the location of this line. The forces consisted of the parties under Messrs. Morris, Hudnutt, Maxwell, Hodges, and McCabe [Blickensderfer to Dodge, letter, Jan. 26, 1869, printed in Report of the Chief Engineer 1870:41].

With specific respect to delineating the line on the east slope of the Promontory range, Blickensderfer informed General Dodge that

On our way westward two lines had been traced on the east slope of Promontory, one at a grade of ninety feet per mile, and the other at a grade of eighty feet per mile. These lines were so nearly balanced in cost and commercial value, that it was difficult to decide which was preferable, but it was thought that the ninety-feet grade line was the better. On returning eastward Colonel Hudnutt reviewed the eighty-feet grade line, and came to the conclusion that it was superior to the ninety-feet grade line, in which view, on examination, I concurred [Blickensderfer to Dodge, Jan. 26, 1869, printed in Report of the Chief Engineer:42].

Another Union Pacific engineer, Theodore B. Morris, had the job of finishing the surveys and examinations at Promontory. After re-examining both lines and making an extended system of surveys, Morris showed "conclusively" and persuaded Blickensderfer "that the eighty-feet grade line on the eastern slope of this range was not only better than the ninety-feet grade line, but superior to any other over this summit" [Blickensderfer to Dodge, letter, Jan. 26, 1869, printed in Report of the Chief Engineer:42).

Assessing the survey efforts and selection of the line for the Union Pacific Railroad, Blickensderfer wished that the work had been better coordinated and less hurried:

In reviewing the season's operations, a feeling of regret occasionally arises that the allotted time within which it became necessary to determine questions of moment in the location of the road was often so short as to preclude the entire, complete, and minute determination of all the facts bearing on the subject which would have been desirable. . . Had the country between Green River and Humboldt Wells been carefully examined in 1867, and the results of such an examination been available when the operations of 1868 were commenced, the labor would have been greatly diminished. As it was, less than half the distance had never been examined by your company, and the lines which had been run were in most cases so meager as to afford little or no assistance. We were obliged to trace our own preliminaries, correct our own first efforts, and fix a final as best we could, from our own results, oftentimes in valleys overflowed for miles in length, in a barren country without inhabitants, with no means of crossing the streams, and with limited opportunities for returning to correct or readjust our work. Under such circumstances we located a line of more than four hundred miles in length, on more than half of which we had no previous survey of any kind to guide us, within less than four month's time; and while I am sure that no radical error exists, it is nevertheless quite probable that in the details of the work improvements could have been effected had more time been at our command [Blickensderfer to Dodge, Jan. 26, 1869, printed in Report of the Chief Engineer:42-43].

On June 10, 1868, the route that led from Echo Canyon over the Promontory range was staked and ready for grading. Between October and mid-December, the Union Pacific had succeeded in laying track to within 37 miles from the mouth of Echo Canyon. Because tunnel construction in Weber Canyon would proceed slowly, the Union Pacific decided to build a temporary track around the canyon so that the time spent building the tunnels would not impede construction farther to the west. By year's end, in addition to construction of the grade to Promontory, work remaining on the Union Pacific line included finishing tunnels, building bridges and grading in Echo and Weber canyons (Reeder 1970:41-42).

Needing to augment the labor force to make the final push to Great Salt Lake, especially in order to complete the grading work, the Union Pacific had negotiated a contract with Mormon President Brigham Young on May 21, 1868. The contract for more than $2 million provided that Mormon crews would do grading for a distance of from 50 to 90 miles; the discrepancy reflected the lingering possibility at the time that the southern route through Salt Lake City might be chosen. The work also involved bridge and trestle work in addition to the building of two tunnels, 300 and 500 feet in length. Young subcontracted the work to three of his sons and to Bishop John Sharp. In the span between June, 1868, and May, 1869, some 5,000 Mormons helped to build the Union Pacific road (Athearn 1969:18-19; Reeder 1970:30-33).

By early fall, 1868, General Dodge had determined that the northern route, even though it bypassed Salt Lake City, was far more advantageous than the southern. The Secretary of the Interior subsequently approved the northern route because of its more favorable alignments and grades, in addition to the greater availability of both wood and water along the northern route (Galloway 1950:131; Reeder 1970:40). Brigham Young and the residents of Salt Lake City were understandably disappointed over the Union Pacific's decision to bypass their city. This decision would require Young and his followers to later build a branch line to Salt Lake City in order to make connections with the primary transcontinental rail line. Although he had promised his full support to the Union Pacific and agreed to accept no contracts from the Central Pacific, Young referred the Central Pacific officials to several Mormon bishops when they inquired as to additional work forces needed by the company as contract labor. Young's referral to the Central Pacific came only a few weeks after the northern route was recommended and approved by the Chief Engineer of the Union Pacific. According to Dodge, Young had told Stanford that "he would not take any work from him himself, but would recommend him to proper persons to take it." Frustrated by Young's actions, Dodge quipped, "perhaps you can see the difference 'tween tweedle dum an' tweedle dee but I cannot" (Dodge to Oliver Ames, letter, Sept. 4, 1868, Grenville Dodge Collection, Council Bluffs Public Library, Council Bluffs, Iowa).

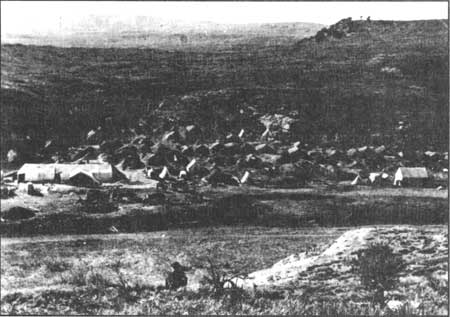

Mormon construction camps reflected the religious zeal of the crews. Twice daily, workers and their families assembled for prayers and on Sundays they attended religious services. The camps, located as near as possible to their work sites, were orderly and quiet. Neither swearing nor drunkenness characterized their construction camps (Arrington 1969:10; Pine 1871:345-346; Reeder 1970:33-35). In Echo Canyon, some 45 of these camps were temporarily established, each associated with a particular ward or Mormon community. Figure 3 is believed to be a photograph of a Mormon campsite in Echo Canyon taken in 1868. At day's end, the Mormons often found time for playing games and for singing as they gathered around campfires, singing such choruses as:

Hurrah! Hurrah! For the railroad's begun!

Three cheers for our contractor, his name's Brigham Young!

Hurrah! Hurrah! we're honest and true,

For if we stick to it's bound to go through [Reeder 1970:36].

|

| Figure 3. "Mormon village . . . Echo Canyon." Source: A. J. Russell photograph No. 109, 1868-1869 Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha, NE. |

Mormon crews worked for the Central Pacific under a contract negotiated in August of 1868 with Ezra Benson of Logan, Utah, and Mayor Lorin Farr and Chauncey West of Ogden. This contract called for the grading of 60 miles of roadbed between Ogden and Monument Point. A second grading contract was similarly negotiated between Mormon leader Lorenzo Snow and the Central Pacific. In mid-December, 1868, Snow reported that his crews grading in the Promontory area had nearly completed their work (Reeder 1970:45-46).

With the assistance of Mormon contracted labor, the Union Pacific built four tunnels through Echo and Weber canyons in the nine months between July 1868 and March 1869. Unlike the granite of the Sierra Nevada, the soft clay rock and sandstone of these canyons meant that every foot had to be reinforced with timbers as blasting progressed. Rushing beyond comprehension at times, the Union Pacific laborers worked through the night by lantern light. Perhaps in too great a hurry, track and rails were sometimes laid directly on snow and ice rather than on ballast or the grade beneath the track. As McCague has noted: "In such a driving rush to shove the iron forward, everyone worked on the thin edge of trouble" (1964:274).

Despite the difficulties of tunnel construction, despite the snow and harsh cold, the Union Pacific grading and track-laying advanced westward. Since the ground was by then frozen, grading also required blasting (Hyde 1895:112, 116). By mid-January, a new end-of-track town, Echo City, was open for its version of hellish business; on January 22, the Union Pacific track reached the 1,000-mile point from Omaha. Nearing winter's end, and after serious delays because of heavy snow in Wyoming, UP track-layers arrived in Ogden on March 8. They were greeted by cheering crowds and a happy procession, complete with artillery salutes and a banner that read "Hail to the Highway of Nations." By mid-March, the Union Pacific had broken ground "on the heavy work at the Promontory," as Leland Stanford put it in a letter to Mark Hopkins (Kraus 1969b:237-237). Describing the terrain at Promontory, Dodge pondered the level of effort it would take to build a railroad there:

Promontory Point, [1] the most difficult summit to make, and where the most intricate line, the heaviest work, the highest grades, and the sharpest curves occur, is a bold backbone running north and south, terminating at its southerly point, between Bear River and Spring Bays of Great Salt Lake, and for a distance of thirty miles dividing the waters of Great Salt Lake and forming these bays, and on the north joining the rim of basin between Blue Springs and Pilot Springs stage stations. The ridge is six hundred feet high, with scarcely four miles of direct ascent from the east, and twelve of descent on the west, devoid of natural ravine or water course. To approach the summit the line has to overcome the elevation by clinging to the rough sides of the ridge, and gaining distance by running up Blue Spring Creek Valley, and winding back again on its opposite side. . . . The six miles of line on the east slope of the mountain has heavy work and a few 6° curves as a maximum, and is by far the most difficult portion of the line west of Weber Canon [Report of the Chief Engineer 1870:9-10].

The Salt Lake City Daily Reporter expected that by the end of March, 1869, the Union Pacific would have 2000 workers building the railroad in the Promontory area (Kraus 1969b:236). In contrast, Central Pacific workers — some 300 to 400 of them — had been at work opening rock cuts on the east slope since early February (Theodore Morris to Grenville Dodge, Feb. 8 and Feb. 16, 1869, GOSP File 104-GMO, GOSP Research Files, Golden Spike National Historic Site). End-of-track construction for both companies simultaneously advanced: by April 6, working at a feverish pace, the Central Pacific track-layers had built track to a point 38 miles west of Monument Point (Silas Seymour to Grenville Dodge, April 6, 1869, GOSP File 104-GMO). Two days later, on April 8, the end of the Union Pacific's track reached Corinne (McCague 1964:286; Reeder 1970:42-44).

Parallel grading work also continued to proceed. Stanford thought that by "crossing us and at unequal grades," that the Union Pacific intended to deny the Central Pacific's right-of-way and to "claim it for themselves and that we must not get on it." On March 1, 1869, in its last days in office, a waning Johnson administration decided to release bonds to the Central Pacific for advance work all the way to Ogden — a decision that Central Pacific officials kept secret for as long as possible. Stanford strongly believed that "if it were known that we had the bonds for unfinished work that the UP would call off their graders." He noted further that the Union Pacific had "changed their line so as to cross us five times with unequal grades between Bear River and the Promontory" (Bain 1999:612-613; Kraus 1969b:237). In a March 13, 1869 telegram to Huntington, Stanford explained that the Union Pacific's grade varied as much as 50 to 80 feet from that of the Central Pacific (Bain 1999:618). For his part, Stanford planned not "to finish up our line, but keep men scattered along it until our track is close upon them." He reasoned that by doing so the Union Pacific would not "attempt to jump our line while it is unfinished and we are working it"(Stanford to Hopkins, March 14, 1869, in Kraus 1969b:237).

It is quite possible that when the UP and CP grading crews, moving respectively west and east, began building parallel grades in the spring of 1869, many of the crews were composed of Mormons working for the Mormon firms that had contracted with the rival companies (Bain 1999:658). Another story — perhaps apocryphal — contends that when the predominately Irish Union Pacific graders met the Central Pacific's Chinese grading crews, they strategically placed blasting powder to explode right when the Chinese workers approached, killing and maiming them horrifically. In retaliation, the story continues, the Chinese then laid their own "grave for their UP counterparts, inflicting similar damage (McCague 1964:294-295). [2] The price of the competition may have thus exceeded the combined costs of physical exhaustion, duplicated efforts and sometimes shoddy construction.

By early April, the need to determine a final connecting point was growing more and more obvious. Union Pacific's Silas Seymour wired railway operations superintendent Webster Snyder to inform him that by April 5 their track-layers had reached a point one mile east of Bear River and that grading was complete from there to the east base of Promontory. Seymour urged the necessity of laying 20 more miles of track quickly so that timber for the UP's large trestle on the east slope of the summit could be delivered. Seymour still hoped that the Union Pacific graders could finish their work over Promontory within a month and that the junction of the two lines would be at Monument Point to the west of the summit. "All this must be done within 30 days," he wrote to Snyder, "or we are whipped by Central for possession of Monument Point" (Seymour to Snyder, April 5, 1869, GOSP File 104-GMO, GOSP Research Files, Golden Spike National Historic Site). As the Senate took up this question, Ohio Senator John Sherman put it this way: "We all know that there is a dispute between the companies as to which shall build the road between Ogden and Monument Point" (1869:495).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr2d.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003