|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 2:

SITE HISTORY (continued)

Completing Construction at Promontory Summit: April-May 1869

On April 11, 1869, in response to the decision to join the rails at Promontory, the Union Pacific ordered a halt to all grading work west of the summit. Just a few days later, on April 14, the Central Pacific similarly stopped all work on its line east of Blue Creek. Despite the decision that specified a meeting point, "competition had become a habit," as historian George Kraus noted. Each company still wanted to win the race by being the first to reach the summit (Kraus 1969b:244).

Two major construction features in the Promontory area — the Central Pacific's Big Fill and the Union Pacific's Big Trestle — were nearing completion by mid-April. Both crossed a deep gorge located roughly halfway up the east slope. Leland Stanford of the Central Pacific had predicted that the Big Fill would require some 10,000 cubic yards of dirt to complete. Mormon workers, signed on with Benson, Farr and West, had been working on the Big Fill since February. Ultimately requiring the efforts of 500 men and 250 teams of horses, the Big Fill rose to a height of 170 feet when done (Kraus 1969b:244; Mann 1969:129). On April 14, 1869, as the job was almost finished, a Salt Lake City Daily Telegraph reporter noted the danger that accompanied this work:

On either side of this immense fill the blasters are at work in the hardest of black lime rock, opening cuts of from 20 to 30 feet depth. The proximity of the earth-work and blasting to each other, at these and other points along the Promontory line, requires the utmost care and vigilance on the part of all concerned, else serious if not fatal, consequences would be of frequent occurrence [Kraus 1969b:244].

Located about 150 feet east of, and parallel to, the Big Fill was the UP's Big Trestle. Over 400 feet long and more than 80 feet high, the trestle was then considered a temporary substitute for an earth fill to be constructed after the roads had met. Union Pacific trestle-builders under the direction of Leonard Eicholtz began work on the structure on March 28, even while Central Pacific crews continued to work on that line's Big Fill (Kraus 1969b:244-245).

By April 26, 1869, the Big Fill was completed and Central Pacific's track had reached a point some 16 miles west of Promontory. The Union Pacific workers, on the east side of summit, were still hurrying to finish the Big Trestle and also had smaller trestles and difficult rock cuts, including Carmichael's Cut and the Last Cut, yet to complete. Central Pacific's Charles Crocker had previously boasted that CP crews could lay 10 miles of track in one day. In response, Union Pacific Vice President Thomas Durant allegedly bet him $10,000 that they could not accomplish this feat. Crocker met the challenge, and at dawn on April 28, the Central Pacific track-layers went to work. Because of the short distance remaining to be covered until they both reached the meeting point — the UP end-of-track was already within 8 miles of the summit at that point — this meant that Union Pacific workers would not have a chance to best the Central Pacific record, should the CP crews prove successful (Best 1969a:46; Kraus 1969b:245; McCague 1964:304-305; Raymond and Fike 1981:19).

In 12 hours, the Central Pacific work gangs — Irish rail-handlers and Chinese support crews — laid 10 miles and 56 feet of track. Although the Central Pacific had identified a relief team, the original eight Irish rail-handlers — George Eliott, Edward Kelleen, Thomas Daley, Mike Shea, Mike Sullivan, Mike Kennedy, Fred McNamara, and Patrick Joyce — took only an hour's break at mid-day and then, refusing to quit, continued working. Relentlessly moving eastward, the crews laid the track at roughly the same pace as a leisurely walk — approximately 240 feet in just over a minute. A reporter for the Alta California presciently remarked that it matched the same pace "as the early ox team used to travel over the plains" (Kraus 1969b:248-250; McCague 1964:306).

The process involved first unloading 16 cars that hauled enough iron rails, spikes, fishplates and other materials for building 2 miles of track. In eight deafening and quick minutes, all of the track-building materials were on the ground. Then teams of six Chinese workers loaded 16 rails, a keg of bolts and a keg of spikes and the necessary fishplates onto iron hand cars. Horses pulled these cars to the end of the track. From here, more Chinese distributed the materials along the roadbed. Then, using nippers to grab each end, the rail-handlers lifted the rails and placed them on the ties, where a track gang bolted and spiked them down. The horses pulled the carts ahead and the process was repeated, over and over again.

Cross-ties had previously been delivered all along the 10-mile stretch. Ahead of the rail handlers, workers called "pioneers" had the job of butting the ties to a line of rope set at a distance from the track center designated by the surveyors. At the end of the track-laying, another crew shoveled ballast under the ties for support. Then came the track-straighteners. Finally, 400 some "tampers" followed to tamp down the ballast. Foremen on horseback shouted directions all up and down the track. As one 2-mile section was completed, the next material train moved as far up the track as possible to start the whole process again.

Keeping pace with the track-laying was the crew constructing the telegraph line. The material trains also carried telegraph poles; these were delivered along the roadbed in wagons. Laborers then fastened cross-arms to the poles. Another work gang dug the holes; a third group hoisted the poles. Another wagon brought the wire forward, which was slowly unwound from a reel as the wagon proceeded to move forward. Another crew quickly attached the wire to insulators. At day's end, the wires were connected to a telegraph set in order to communicate with supply points to the west (Galloway 1950:159).

At 1:30 that afternoon, Charles Crocker signaled it was time to break for dinner. By then, the CP crews had laid 6 miles of track. The dinner spot — now Rozel — earned the name "Victory" from workers who were confident that they could lay another 4 miles before quitting time. Camp train boss, James Campbell, served a much-appreciated hot meal to workers and audience alike. The Union Pacific had taken the day off to watch its counterparts race against time and exhaustion.

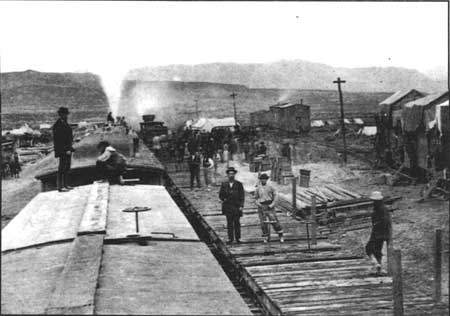

By 7:00 that evening it was time to quit, and the Central Pacific crews had done it —just over 10 miles in one day. The afternoon pace was a bit slower because rails had to be curved. To do this, workers placed the rails between blocks and hammered curves into them. The total job required the use of 25,800 ties; 3,520 rails, 55,000 pounds of spikes; over 7,000 poles; and nearly 15,000 bolts. The eight Irish rail-handlers had each lifted 125 tons. The same Central Pacific time book that lists their names indicates that they received four days' wages for the work. It is unknown if the Chinese workers received any additional pay for their efforts that day, but all could take enormous pride in the achievement (Bain 1999:639-640; Best 1969a:46-47; Kraus 1969b:252; McCague 1964:305-308; Raymond and Fike 1981:19-21). Figure 4 shows a railroad camp near Victory (Rozel) near the end of the Central Pacific's 10 miles of track laid in a day.

|

| Figure 4. "Railroad Camp near Victory [Rozel]." 1869. Source: Alfred Hart Photo No. 350, Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha, NE. |

Present to witness the 10-mile day and realizing how close the Central Pacific crews were to the summit, Stanford wired Huntington, imploring him to do whatever he could to convince the Union Pacific to cease its grading work and temporary construction on the east slope. Stanford hoped that Union Pacific officers would agree to adopt the Central Pacific's grade and build its track on it. Despite Huntington's assurances that the April 9 agreement stipulated that the Central Pacific line to Ogden would be adopted, Union Pacific contractors received no orders to that effect. Historian David Bain has concluded that "in this matter as in so many others inertia dictated; with Dodge and Ames against it, apparently the government commissioners and the interior secretary had decided on a status quo policy which would 'not require serious action by the Government,' as a Union Pacific lobbyist wrote Dodge" (1999:640).

Leonard Eicholtz also witnessed the Central Pacific's remarkable feat. In his diary that evening, he wrote: "Saw them lay their big day's work — ten miles of iron." With Eicholtz were UP's Sidney Dillon, Thomas Durant, and Grenville Dodge. Eicholtz noted that he and this party were on their way back to "Echo, but on reaching Corinne, came back and gave orders to haul iron and ties to [the] summit tomorrow and lay track from there east" (Eicholtz diary, April 28, 1869, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming). [3] As a result, Casement's crews hauled ties and rails in wagons around the Big Trestle and Carmichael's Cut to the summit and began building track eastward from that point. Railroad historian George Kraus explained that by doing so the Union Pacific track-layers could continue building track instead of waiting for the graders to finish their work (1969b:256), while another analyst, Maury Klein, contended that the Union Pacific intended to create a barrier so that the Central Pacific track would indeed end at Promontory Summit (1987b:219).

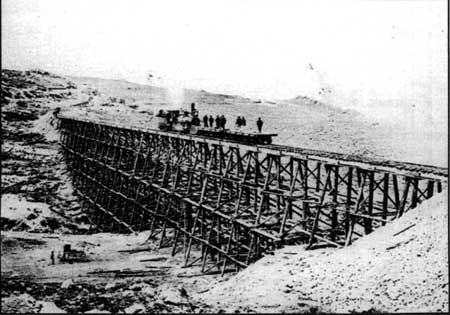

On April 30, 1869, the Central Pacific line reached the summit at Promontory. The Alta California announced: "The last blow has been struck on the Central Pacific Railroad, and the last tie and rail were placed in position today. We are now waiting for the Union Pacific to finish their rock-cutting." (Kraus 1969b:256). Additionally, the Union Pacific crews still needed to complete the work on their trestles. As the Alta California had reported a few days earlier: "Meantime, the Union Pacific road creeps on but slowly; they have to build a tremendous trestle work... .But their rock cutting is the most formidable work." Noting the inefficient duplicative effort, the newspaper continued: "It seems a pity that such a big job should be necessary when the grading of the Central Pacific is available and has been offered to them." Commenting further on the construction of the Big Trestle, the Alta California found the structure to be "like a frame gossamer; one would think that a carpenter's scaffolding were stouter" (Kraus 1969b:253). Referring to the structure in a May 4 letter to Huntington, Charles Crocker wrote that "the track passes over a piece of trestle which if we had possession we would not attempt to run over, but would immediately replace with new trestle or fill" (Bain 1999:640).

On May 2, the San Francisco Bulletin reported that "the great trestle-work four miles east of the Summit is nearly finished. Mr. Casement says it is only temporary, and will be filled up during the summer." The Bulletin further stated that the "track-layers of the Union Pacific Company will be kept working at either end as the graders get out of the way" (Klein 1987b:219; Kraus 1969b:256).

During the first week of May, working day and night, Union Pacific work teams made great strides to finish the remaining section of track. On May 5, they finished the Big Trestle and a train loaded with track-building materials powered across it (Figures 5 and 6). That evening they set off the last blast to complete Carmichael's Cut. The next day, May 6, they drove the last spike to finish a smaller trestle located between Carmichael's Cut and Clark's Cut. Grading crews then worked their way through both cuts, swung around the head of a ravine, then moved through a final cut to join the grading that had been previously finished in the summit's basin. Cross-ties and rails had already been positioned here to enable track-laying, and UP workers quickly installed a 2,500-foot side track at the summit (Eicholtz diary, May 5, 1869, May 6, 1869; Utley 1960:59).

|

| Figure 5. Overlooking north-northeast along the completed Big Trestle. Source: A.J. Russell, 1869. |

|

| Figure 6. Detail of west abutment—Union Pacific's Big Trestle. Source: A.J. Russell Photo No. 515, 1869, Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha, NE. |

By May 7, the Union Pacific crews were inching ever more closely to completion. The Alta California reported that "This afternoon the Union Pacific finished their track to a switch forty rods [660 feet] east of the end of the Central, on the new side track down to a point opposite the Central." To celebrate the near completion of the two lines, Union Pacific's Engine No. 66 pulled up next to the Central Pacific railhead, a mere 100 feet to the southeast, where the Central Pacific's Engine No. 62, named the Whirlwind, was sitting on its own track. When No. 66 let off steam, the Whirlwind responded with its own sharp whistle. As the Alta California reporter on the scene declared, this marked "the first meeting of locomotives from the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts" (Kraus 1969b:257; Utley 1960:59).

While all of this construction on the east and west slopes occurred during the spring of 1869, construction camps clustered around major work sites as each rail line progressed towards the meeting point at the summit. New "Hell-on-wheels" towns quickly mushroomed at the end of Union Pacific's track. The character of these towns contrasted sharply with that of the Chinese and Mormon camps. In late March, a reporter for the Salt Lake City Deseret News had noted the birth of Corinne, "built of canvas and board shanties. The place is becoming civilized," quipped the reporter, "several men having been killed there already, the last one was found in the river with four bullet holes through him and his head badly mangled" (Kraus 1969b:237-238; McCague:294).

"From Corinne west thirty miles," observed the same reporter, the grading camps present the appearance of a mighty army. As far as the eye can reach are to be seen almost a continuous line of tents, wagons, and men." The reporter continued: "Junction City, twenty-one miles west of Corinne, is the largest of any of the new towns in this vicinity. Built in the valley near where the lines commence the ascent of the Promontory, it is nearly surrounded by grading camps. . . . The heaviest work on the Promontory," the reporter additionally explained, "is within a few miles of headquarters. Sharp & Young's blasters are jarring the earth every few minutes with their glycerine and powder, lifting whole ledges of limestone rock from their long resting places, hurling them hundreds of feet in the air and scattering them around for a half mile in every direction." The reporter also believed there was "considerable opposition between the two railroad companies, both lines run near each other, so near that in one place, the U.P. are taking a four feet cut out of the C. P. fill to finish their grade, leaving the C.P. to fill the cut thus made, in the formation of their grade" (Kraus 1969b:238).

The same Deseret News reporter further observed that "several dance houses are now in full blast, astonishing the natives by the manner in which they are developing the resources of the Territory. I will venture the assertion that there is not less than three hundred whiskey shops between here and Brigham City." Noting the numbers of "heavy contractors on the Promontory," the "heaviest" appeared to be named "'Red Jacket' [a whiskey brand] . I notice nearly every wagon that passes have a great many boxes marked with his name" (Kraus 1969b:241).

Mormon pioneer J. L. Edwards later recalled the "old Carmichael Camp and Dead Fall camp" (Figure 7) on the east slope of the summit, "which were commonly referred to as having dead men every morning for breakfast, so wild and lawless were the members thereof All the scum of the earth used to gather there," Edwards continued, "and brawls were frequent. Cattle stealing was the rule and no man was safe when coming up with these ruffians." Yet, Edwards also remembered a pleasant evening when he had supper "in the large dining tent at the Dead Fall camp." Black waiters "in white aprons" served the meal "with as much pomp and ceremony as the service at the finest hotels in the country" (A Brief Biography, 1917:21, File:H1412, Central Files "H" — History, Golden Spike National Historic Site). This surely was the exception to prove the rule, however. Union Pacific photographer, C. R. Savage, counted the numbers of murders at Dead Fall and other camps in the vicinity since mid-April: "I was creditably informed that 24 men had been killed in the several camps in the last 25 days. Certainly a harder set of men were never congregated together before" (Kraus 1969b:258). Bernice Gibbs Anderson reiterated this depiction when she wrote:

Four of these camps were located about twenty miles west of Corinne . . . .Gambling tents where faro, roulette, Chinese fan tan and Mexican monte held sway, were numerous. Whiskey flowed freely, and blood almost the same . . . .Every form of vice was in evidence and it seemed as though all the toughs in the west had gathered here. The law made no attempt to pervade these camps. . . (Anderson 1965:353-354).

|

| Figure 7. Union Pacific's Camp Dead Fall — east slope of the Promontories. Source: A. J. Russell photo No. 533, Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha, NE. |

On May 8, 1869, an incident in one of the Chinese camps turned uncharacteristically violent. A Chinese "tong war" erupted between two rival companies involving several hundred laborers of the See Yup and Teng Wo companies. Idle at Victory [Rozel] since their work was complete, the groups argued over a $15 debt. The argument escalated into a fight in which the combatants used "every conceivable weapon. Spades were handled, and crowbars, spikes, picks and infernal machines were hurled between the ranks of the contestants. Several shots were fired, and everything betokened the outbreak of a riot." Then cooler heads prevailed when some of the more influential Chinese workers, Superintendent James Strobridge and others stepped in to break up the fight (Kraus 1969b:257).

As construction neared completion on the summit, however, crew bosses started ordering their workers to vacate the area. Accordingly, the lines of white canvas tents began to disappear over the eastern and western horizons, although a few Chinese groups did remain in the area in order to complete work on the line after the rails were joined. On May 5, the Alta California reported that:

The Central Pacific force are nearly all gone already, and that of the Union is going fast. Ninety of the latter left for the East this morning, and a hundred more go tomorrow, and the rest will soon follow. Between six and seven hundred graders and one hundred track layers are working on the Union Pacific, and now only twenty-five feet of rock-cutting remains to be finished in the Promontory Range at this moment, that is nearly all drilled and ready for blasting. Work will be carried on all night, and by tomorrow noon the grading will be entirely completed [Kraus 1969b:256].

At Blue Creek, Savage noted the "returning 'democrats'" who were "piled upon the cars in every stage of drunkenness. Every ranch or tent has whiskey for sale." "Verily," Savage concluded, "men earn their money like horses and spend it like asses." At Promontory Summit, where a few workers remained, Savage counted a "1/2 doz. tents and Rum holes"(Savage, diary entries, May 8 and 9, 1869, File:119-Say, GOSP Research Files, Golden Spike National Historic Site).

Initially, May 8 had been set for the day to celebrate the joining of the rails. But, an unforeseeable event literally held up Union Pacific Vice President Thomas Durant as he headed west for the occasion. Two days earlier, on May 6, as Durant's train pulled into Piedmont, a mob of some 300 disgruntled armed men — all tie-cutters and graders who had been laid off with back pay owed them — stopped the train. They uncoupled the official car, swarmed around Durant, and demanded the pay that had been due them for four months. Durant was not carrying anything close to the demanded sum — anywhere from $12,000 to more than $200,000, according to different sources, and so wired Oliver Ames in Boston to send the money. Instead, Ames quickly replied by telegram, asking Dodge in Salt Lake City to send troops to rescue Durant. Dodge complied, ordering a company of infantry from Fort Bridger, but another UP official in the area, Sidney Dillon, insisted that the troop train pass by Piedmont without stopping. On May 7, Dodge again wired Ames: "Tie outfit at Piedmont hold . . . Durant under guard as hostage for payment of amount due them. You must furnish funds on Dillon's call." The following day, May 8, Dodge sent a second telegram to Ames, stating that the best amount to send would be $500,000 so that others besides the 300 at Piedmont could be paid what was owed them. Ames somehow scraped together this sum out of the company's straitened assets and wired it west so that the workers could be paid and Durant could be set free (Ames 1969:322-323; Bain 1999:649-650; Kraus 1969b:260-261; McCague 1964:309-311). [4]

Other Union Pacific officials were delayed a day at Weber Canyon when the trestle-bridge at Devil's Gate needed to be repaired before the train could proceed westward. They finally arrived at the summit on May 9. While Stanford together with other Central Pacific officers and invited guests — who had arrived two days earlier — waited for the UP officials, they enjoyed dining and toasting the occasion with the Union Pacific's track-laying contractor, General Jack Casement. Accepting an invitation to inspect part of the Union Pacific's line, they also rode to Weber Creek Station, some 26 miles east of Ogden. On Sunday, May 9, they returned as far west as Monument Point and visited the shore of Great Salt Lake (Best 1969b:73; Kraus 1969b:258; Utley 1960:63).

Final construction also proceeded on May 9. On that day, a rainy one, Union Pacific track layers finished the last 2,500 feet of track, except for the length of rail to be laid during the next day's celebration of the joining of the two lines. They also constructed a "wye" where locomotives could turn around on the track (Utley 1960:63). [5] That evening, the clouds started to lift and nothing remained to do except prepare for the driving of the last spike.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr2f.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003