|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 2:

SITE HISTORY (continued)

The Wedding of the Rails at Promontory Summit: May 10, 1869

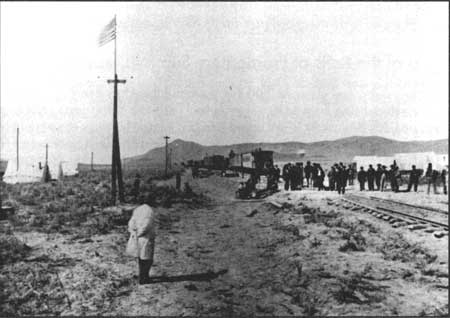

The day dawned sunny and clear. At 7:00 that morning, the American flag — somewhat oddly, a 20-star version dating from 1819 — was hoisted onto one of the nearby telegraph poles (Ketterson 1969a:64-65) [Figure 8]. The Central Pacific Chinese laborers who would be responsible for preparing the last few feet of roadbed and laying the final track began to get ready for the day. The setting for the ceremony was situated in a basin at the summit at approximately 5,000 feet above sea level. Stretching for 3 miles in width, the basin was surrounded by higher rounded mountains. Typical of a dry climate, the limited vegetation included sagebrush, greasewood, bunch grass, and a few cedars in the drainages on the surrounding mountains. The junction point, located at the eastern end of the basin, also lay about 3-1/2 miles east of the place where the Central Pacific crews had completed their feat of building more than 10 miles of track in one day (Bowman 1969:92; Kraus 1969b:270). Describing the setting, a reporter for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper on the scene that day wrote:

After a pleasant ride of about six miles we attained a very high elevation, and passing through a gorge of the mountains, we entered a level, circular valley, about three miles in diameter, surrounded on every side by mountains. The track is on the eastern side of the plain, and at the point of junction extends in nearly a southwest and northeast direction.

Two lengths of rail are left for today's work. We arrived on the ground twenty minutes past eight A.M., and while we are waiting we will look about us a little. A large number of men [are] at work ballasting and straightening the track, also building a "Y" switch. Fourteen tent houses for the sale of "Red Cloud," "Red Jacket," and "Blue Run," are about evenly distributed on each side of the track [Kraus 1969b:270-272]. [6]

|

| Figure 8. Image early in the day — May 10, 1869. Looking southwest along the grade. Note the irregular Union Pacific ties on the grade east of the Last Spike Site. Source: A.J. Russell photo No. 538, Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha, NE. |

Some twenty minutes later, at about 8:45, carrying many passengers from Nevada and California as guests of the CP, a Central Pacific train arrived, pulled up to a siding to join James Strobridge's construction train and to await the arrival of the Union Pacific train. Just a while later the Union Pacific's train, pulled by locomotive No. 119 with Sam Bradford at the throttle, arrived. The group aboard this train included: UP officials Thomas Durant, Sidney Dillon, and John Duff; Chief Engineer General Dodge and consulting engineer, Silas Seymour; the Casement brothers; construction superintendents Sam Reed and James Evans; Leonard Eicholtz, and a number of guests, including Reverend John Todd of Pittsfield, Massachusetts who would provide the benediction to bless the union of the two roads. Behind Durant's train came another carrying officers and men of the 21st regiment of the U.S. Army, en route to the Presidio in San Francisco. The army brought its own band; also on the scene was the Tenth Ward Headquarters Band from Salt Lake City, resplendent in colorful uniforms. Other invited guests included Mormon Bishop John Sharp and Ogden Mayor Lorin Farr, officially representing Brigham Young at the ceremony, scheduled to begin at noon (Bain 1999:660; Best 1969a:50-51; Kraus 1969b:272).

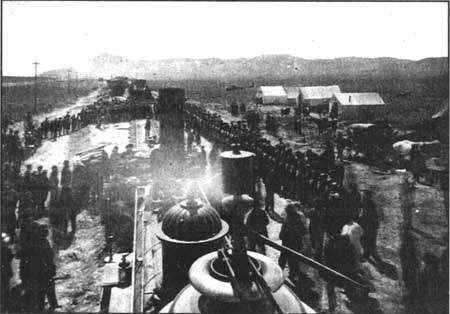

A few minutes after 11, the Central Pacific's engine, Jupiter, No. 60, driven by George Booth, brought Leland Stanford's special train from the west. Joining Stanford were: California Chief Justice S. W. Sanderson; Governor A. P. K. Safford of Arizona; F. A. Tritle, soon to be governor of Nevada; several of Stanford's personal friends, including Dr. J. D. B. Stillman of Sacramento; Dr. W. H. Harkness, editor of the Sacramento Press; and photographer A. A. Hart (Best 1969b:71-73; Section on Golden Spike, Historical Catalogue, Union Pacific Historical Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1951, p. 17) [Figure 9].

|

| Figure 9. Looking east along the completed grade — May 10, 1869. Source: Alfred Hart Photo No. 288, Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha NE. |

For about an hour and a half before noon, Chinese workers did the grading for the remaining rails, laid the necessary ties, and made final preparations for the ceremonial driving of the last spike. Because of a plan to connect telegraph wires to the maul to signal when the final spike in the transcontinental railroad had been struck, wires were strung from the nearest CP and UP telegraph poles down to a small table alongside the gap between the two rails. Here, much like twentieth-century television reporters announcing that the Eagle had landed on the moon, telegraph operators W. N. Shilling, W. R. Fredericks, Howard Sigler and Louis Jacobs waited to sound the union of the rails across a rapt and excited nation (Bowman 1969:94; Kraus 1969b:273).

By noon the temperature had risen to almost 70 degrees. Some news accounts estimated that the crowd numbered as many as 3,000; others reported a much lower figure of 500. The group, which included a few children and perhaps as many as twenty women, mostly wives of military officers and other visitors, including Sam Reed's wife and daughter, began to mill closer to the site where Durant and Stanford would drive the last spike. The Jupiter and No. 119 were uncoupled from their trains and pulled forward towards the end of the tracks (Figure 10). Soldiers stood at parade-rest on the north side of the tracks. Jack Casement asked everyone to withdraw a bit so that all could see the ceremony. At about 20 minutes after 12, the key operator alerted the Western Union system that in another 20 minutes, the last spike would be driven and that all wires should be kept clear in anticipation. Then, the construction superintendents for both companies, James Strobridge and Sam Reed, carried a polished laurel tie to the connecting point. The ceremonial tie had been presented by West Evans, tie-contractor for the Central Pacific. Measuring over 7 feet in length, it had an 8-by-6-inch silver plate on the top and at its center. Earlier, auger holes had already been bored into it. The inscription on the tie read: "The last tie laid on the completion of the Pacific Railroad, May, 1869." Inscribed also was a list of railroad officers and directors (Bowman 1969:87; Kraus 1969b:273). [7]

|

| Figure 10. Promontory Summit immediately prior to the Last Spike ceremony. View is to the southwest towards Promontory Hollow. Source: Alfred Hart photo, #357. |

Led by their boss, H. H. Minkler, Chinese workers carried the first of the two remaining rails to the last gap in the tracks. An Irish team under foreman Michael Guilford then brought the final rail. The engines blew their whistles and the crowd cheered. One soldier exclaimed: "We are all yelled to bust." At about half past 12, the telegraph sent the following message:

To everybody. Keep quiet. When the last spike is driven at Promontory Point [Summit], we will say "Done!" Don't break the circuit, but watch for the signals of the blows of the hammer. Almost ready. Hats off; prayer is being offered [Kraus 1969b:273].

Edgar Mills, a banker from Sacramento, in the role of master of ceremonies, announced the order of events. Reverend Todd then asked for a blessing upon the wedding of the rails: "We desire to acknowledge thy handiwork in this great work, and ask thy blessing upon us here assembled, upon the rulers of our government and upon thy people everywhere; that peace may flow unto them as a gentle stream, and that this mighty enterprise may be unto us as the Atlantic of thy strength, and the Pacific of thy love." Various guests then spiked the last rails with iron spikes, prior to the driving of the golden spike. These included F. A. Tritle, railroad commissioners J. W. Haines and William Sherman, and Henry Nottingham, president of the Michigan Southern & Lake Shore Railroad (Bowman 1969:95; Kraus 1969b:274).

At 12:40, the telegraph operator informed his many listeners: "we have done praying. The spike is about to be presented." Dr. Harkness of Sacramento then presented Thomas Durant with the golden spike, the first of several ceremonial spikes, including a second gold spike, used to mark the occasion. A San Francisco businessman, David Hewes, had donated the first and more valuable of the two golden spikes. Made by Schulz, Fischer & Mohrig, also of San Francisco, it was nearly 6 inches long, weighed over 14 ounces and was cast from 350 gold dollars. On all four sides the golden spike was inscribed with the names of the railroad officers and directors and the name of the donor. The spike's top read: "The Last Spike." Attached to the tip of the spike was a gold sprue, or an unfinished piece of gold, that was detached and later made into momentoes for several of the principal railroad officials. The smaller second gold spike, donated by Frank Marriott of the San Francisco News Letter, was worth about $200. [8] Durant then placed both the golden spikes in the previously bored auger holes (Bowman 1969:95-96).

Tritle from Nevada then presented Leland Stanford with a silver spike. E. Ruhling & Co., assayers in Virginia City, donated the silver and directed the making of the spike. In size it matched the Hewes golden spike. Rough forged at the time of the ceremony, it was later inscribed with the words: "To Leland Stanford President of the Central Pacific Railroad. To the iron of the East and the gold of the West Nevada adds her link of silver to span the continent and wed the oceans." Stanford placed this silver spike in another auger hole in the laurel tie at the west rail (Bowman 1969:82, 96). [9]

Next, the fourth ceremonial spike was presented by Arizona Governor Safford to Stanford. Made of a combination of iron, silver and gold, it carried the inscription: "Ribbed with iron, clad in silver and crowned with gold [,] Arizona presents her offering to the enterprise that has banded a continent, dictated a pathway to commerce. Presented by Governor Safford." Upon receiving it, Stanford placed this spike in the last holes of the ceremonial laurel tie. There may also have been two other gold and silver spikes given by Montana and Idaho for the occasion but reports are inconclusive concerning these additional ceremonial pieces (Bowman 1969:82-85, 96).

On behalf of the Central Pacific, Stanford offered his thanks for the "golden and silver tokens of your appreciation of the importance of our enterprise to the material interests of the whole country, east and west, north and south." Emphasizing the transcontinental railroad's significance especially to commerce and transportation, Stanford continued: "The day is not far distant when three tracks will be found necessary to accommodate the commerce and travel which will seek a transit across the continent." Chief Engineer Grenville Dodge offered these words on behalf of the Union Pacific: "the great [Thomas] Benton proposed that some day a giant statue of Columbus be erected on the highest peak of the Rocky Mountains, pointing westward, denoting that as the great route across the continent. You have made that prophecy today a fact. This is the way to India" (Kraus 1969b:278-279).

After the presentation of the ceremonial spikes, L. W. Coe, president of Pacific Union Express Company, handed Stanford a silver-headed maul. This maul, or sledge, as it was also called, had a hickory handle made by a San Francisco firm, Conroy & O'Connor. Another San Francisco business, Vanderslice & Company, had provided the heavy silver plating. [10] With the silver maul, Stanford most probably gave only token light blows to the group of ceremonial spikes. He then used a regular maul — the one that had been wired — to hit the last spike. He stood on the south side of the laurel tie while Durant stood outside of the rail on the north side of the tie waiting for his turn to also strike the last spike (Bain 1999:662-663; Bowman 1969:86, 96). [11]

As evidence of their nervousness perhaps and no doubt their inexperience with using a maul to pound in railroad spikes, both Stanford and Durant missed hitting the golden spike with their first blows. Regardless, the Union Pacific telegraph operator, Watson Shilling [12] tapped the three dots signifying the blows anyway, until at 12:47 "d — o — n — e" shot across the wires. The Union Pacific had built the railroad from Omaha to Promontory for a distance of 1,086 miles; the Central Pacific had built the road for a distance of 690 miles from Sacramento to Promontory, for a total length of 1,776 miles.

A magnetic ball on the dome of the capitol in Washington, D.C., then fell to note the joining of the rails. Symbolizing the accomplishment's unifying effect, cities all over the country exploded in celebrations. In San Francisco, the fire-bell in city hall rang while 220 guns saluted the event at Fort Point. In New York City, another 100-gun salute was fired. Bells were rung in Philadelphia. A huge crowd in Buffalo sang "The Star Spangled Banner." A 4-mile-long procession gathered in Chicago. In Sacramento, where crowds had also celebrated on May 8, when the ceremony was originally scheduled to be held, cannon, bells and whistles filled the air along with the shouts of thousands of excursionists brought on free trains to the city from the surrounding valleys and mountains. Addressing the California Assembly, E. B. Crocker, brother to Charles and himself a director of the Central Pacific, proposed a toast to the "greatest monument of human labor." One of the few to also honor the contribution made by the thousands of Chinese workers, he added: "I wish to call to your minds that the early completion of this railroad we have built has been in large measure due to that poor, despised class of laborers called the Chinese — to the fidelity and industry they have shown" (Bowman 1969:96-98; Kraus 1969b:281; Saxton 1966:151).

Closer to Promontory, in Ogden guns were fired for 15 minutes straight from the courthouse, city hall and Arsenal Hill. All businesses had closed in order to celebrate. Within a little more than an hour, 7,000 people had gathered at Ogden's new tabernacle to hear speeches and music — a program that ended with "Hard Times Come Again No More." In Salt Lake City, the Mormon Tabernacle overflowed with people, cheering the event (Kraus 1969b:281).

Yet more features of the ceremony remained: General Dodge and the CP's Samuel Montague next struck the gold and silver spikes. Military officers and some of the women then took their turn. When all the spikes were in place, the two engines nosed forward to touch. Engineers Bradford and Booth each christened the other's engine, smashing bottles of champagne over them, and then shook hands (Kraus 1969b:282). Photographers tripped their camera shutters to capture the moment, providing another testament to the role technology had played in the entire enterprise of building the transcontinental railroad and in celebrating this union.

Lastly, to conclude the festivities, the two engines crossed over the final link in the line. First, the CP's Jupiter backed up and the UP's No. 119 crossed over the connecting spot. Then No. 119 returned to the siding while the Jupiter moved across the junction, thereby signaling the new ability to traverse the nation by train. The ceremonial spikes were then lifted and the laurel tie removed. They were replaced by a regular tie, spiked with regular iron spikes. [13] Representative of a different ethos regarding preservation, relic hunters immediately splintered the last tie into pieces for souvenirs. Even the last rail was reportedly broken into keepsake pieces. As many as six "last ties" and two "last rails" may have been finally laid before the appetite for momentoes was sated. Perhaps in the end it was Chinese workmen who laid the final tie and drove the last spike (Bowman 1969:100; Kraus 1969b:282-284; McCague 1964:332; Rae 1871:194).

In the meantime, Stanford and Durant and the other railroad officials had begun sending and receiving congratulatory telegrams. To President Ulysses Grant they wrote:

Promontory Summit, Utah, May 10, 1869

The last rail is laid, the last spike driven. The Pacific Railroad is completed. The point of junction is 1,086 miles west of the Missouri River, and 690 miles east of Sacramento City.

Among the telegrams that they received was the following from the mayor of New York City, addressed to the presidents of both companies: "To you and your associates we send our hearty greetings from the great feat this day achieved in the junction of your two roads and we bid you God speed in your best endeavors for the entire success of the trans-atlantic highway between the Atlantic and the Pacific for the new world and the old" (Dodge, n.d., "Data Chronologically Arranged for Ready Reference in Preparation of a Biography of Grenville Mellon Dodge," Grenville Dodge Collection, Council Bluffs Public Library, p. 952).

After the ceremony, Stanford invited all the UP principals for a luncheon in his car where fresh California fruit was served and the champagne continued to flow freely. Dodge remembered a speech that Stanford gave in which he criticized the federal subsidies as being more of a detriment than a benefit. According to Dodge, the statement "struck everyone so unfavorably that Dan Casement, who was feeling pretty good, got up on the shoulders of his brother, Jack," and stated the following: "If this subsidy has been such a detriment to the building of the roads, I move you sir that it be returned to the United States Government with our compliments." This roused a great cheer, but as Dodge acknowledged, "put a very wet blanket" over the remainder of the luncheon. He recalled also that those who were present remembered Dan Casement's response "for years and years afterwards" (Dodge, n.d., "Data Chronologically Arranged for Ready Reference in Preparation of a Biography of Grenville Mellon Dodge," Grenville Dodge Collection, Council Bluffs Public Library, pp. 953-954).

Between 5 and 6 o'clock, the parties dispersed and the wedding celebration was over. In Promontory itself that evening, however, the festivities continued. These involved a "torchlight procession, banquet, and 'grand ball' for which the Central Pacific would later pay the bill — three thousand dollars all told" (McCague 1964:332). A few years later, when John Erastus Lester passed through on the transcontinental train, he noted that the rails had joined at Promontory. "Interest will always attach to this place," he wrote, "as being the scene of the ceremonies, grand yet happy, solemn yet full of gayety, which took place at the driving of the last spike. The lightning sounded the stroke which welded the iron bands uniting the oceans" (Lester 1873:47-48).

Although other rail lines would be built that also joined the Atlantic and the Pacific, there could only be one "first" transcontinental railroad and Promontory Summit marks the place where what many hold as the greatest engineering feat of the nineteenth century was completed. The train brought speed and ease of travel. Building a rail line that connected East to West facilitated settlement and commerce and changed transportation in ways that perhaps a late twentieth-century mind — growing accustomed to the possibilities of space travel — cannot fully apprehend. By spurring the settlement and economic development of the West this rail line also hastened the end of the American Indians' way of life. Congress had said that the transcontinental railroad must be completed by 1876. The Central Pacific and the Union Pacific had done it in less than half the time, in just six and one half years. Reflecting on the accomplishment over 20 years later, Union Pacific's Sidney Dillon wrote:

People who thought for a long time that the whole scheme was wild and visionary began after a while to realize that out there on the "Great American Desert" an extremely interesting enterprise was afoot, and that whatever came of it one thing was certain, the world had never seen railroad building on so grand a scale under such overpowering disadvantages and at such a rapid rate of progress [Dillon 1892:257].

Remembering the ceremony held on May 10, 1869, Dillon noted its simplicity and the remoteness of the location. "But our feeling was that however simple the ceremony might be," he recalled, "the people of the whole country, who had kept in such close touch with us and had given us such sympathy and encouragement from the beginning, should be with us in spirit at the culminating moment and participate in the joy of the occasion" (Dillon 1892:258). The telegraph had made that possible. Photographs would also help celebrate and preserve the moment and the image of the place where technology and resources — both natural and financial — had joined with human brawn and ingenuity to span the continent with iron rails. After the ceremony at Promontory Summit, Sidney Dillon and the other Union Pacific officials "started on their return, and the next day, May 11, 1869, trains began running regularly over the whole line. New York was in direct rail communication with [Sacramento], and a new empire was thrown open in the heart of the continent" (Dillon 1892:259). [14]

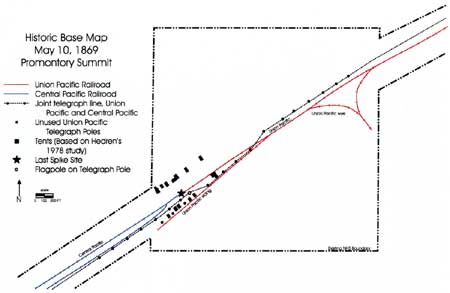

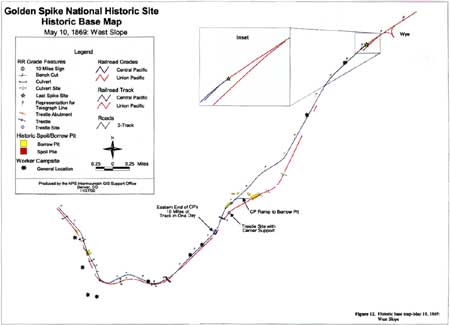

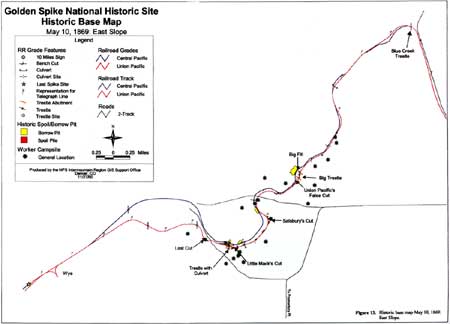

Figures 11, 12, and 13 show the configuration of historic resources within the NHS boundaries as of May 10, 1869.

|

| Figure 11. Historic Base Map—May 10, 1869: Promontory Summit. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Figure 12. Historic Base Map—May 10, 1869: West Slope. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Figure 13. Historic Base Map—May 10, 1869: West Slope. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr2g.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003