|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 2:

SITE HISTORY (continued)

Promontory Station: Post-Celebration, 1869, through Spring of 1870

Just one day after the driving of the golden spike, the first train arrived from the east carrying mists who had hoped to attend the ceremony on May 10 but who had been delayed by the eat of floods at Weber Canyon. The group had traveled from New York to Chicago on the New York Central & Hudson River and the Michigan Southern & Lake Shore railroads, then to Council Bluffs on the Chicago & Northwestern, then to Omaha by ferry across the Missouri River, where they boarded the Union Pacific to cross the plains and the Rockies. They arrived at Promontory during the early morning of May 11 where accommodations were almost non existent. A Central Pacific train to take them any farther west was not available until that night, so they waited all day without benefit of shelter. One of the travelers, a W. L. Humason of Hartford, Connecticut, later remembered of Promontory "nothing but sand, alkali, and sage brush" (McCague 1964:335-336).

On the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, at a station town called Colfax, Humason's group met another excursionist train headed for Omaha that would also change trains in Promontory. On May 15, less than a week after the ceremony at Promontory, both the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific began regular transcontinental passenger service. Trains left daily from Omaha and Sacramento on a trip that took five days to complete. After a 12-hour steamship ride up the Sacramento River from San Francisco and by making connections to Chicago and New York, a passenger could leave the Pacific Coast and arrive on the East Coast seven and a half days later. Until December of 1869, after Ogden had become the official terminus where passengers had to change rail lines, as the congressional resolution of April 10, 1869 had stipulated, Promontory grew livelier but, without sources of water and fuel, the station town was never able to wholly thrive (Anderson 1968:7-8; Section on Terminus, Historical Catalogue, Union Pacific Historical Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1951, pp. 14, 19). [15]

Another portrait of Promontory right after the wedding of the rails was painted by Isaac Morris, a commissioner sent to the area to examine unaccepted portions of the Union Pacific Railroad. According to the Union Pacific's congressionally sanctioned charter, every 40-mile section of completed road had to meet the criteria of a "first-class railroad" before the company could obtain legal title to the lands on each side of the finished road as part of its total federal subsidy. Assigned to report on sections of the UP line that had not met the criteria, Morris submitted his report on May 28, 1869. He described the Promontory area in this way:

This summit is a considerable plateau, covered with artemisia, and quietly resting between two mountain combs or crests. Some thirty tents and a few board sheds mark the spot. The trader had reached it with his wares as soon as the road itself. It is a lonely and desolate locality, without water or fuel, both of which have to be brought from a distance, and Promontory City, as it is called, is not likely to become a commercial emporium, while it will have some fame and a romantic interest attached to it as the place where the Atlantic and Pacific first embraced [Morris 1869:5].

Morris noted further that "no railroad buildings have been erected there, except one or two mere sheds for the storage of baggage and the use of the telegraph" (1869:5) [Figure 14]. Far from excusing some of the track in the road because of the race to complete it, Morris thought that the speed with which it was built had derived principally from abject greed. The result was a railroad poorer in quality than he believed the substantial congressional subsidy had warranted:

Evidently the first and, it may be said, natural object of the company was to extend the line of its road without regard to much, if anything, else than what was indispensable to the necessities arising out of its construction. Five hundred and thirty miles, as I was informed, were built within the past year, and, to repeat the idea just expressed, the whole road was pushed forward in too much of a hurry, both in regard to economy and durability. There was a temptation to do this offered by the subsidies and lands too great for poor, avaricious human nature to resist [Morris 1869:5].

|

| Figure 14. Looking east along the railroad grade through Promontory Summit — ca. late 1869 or 1870. Source: A. J. Russell photo No. 536, Union Pacific Railroad Archives, Omaha, NE. |

Because Congress had not predetermined a meeting point, and because whichever company built the most road would receive the greater subsidy, a desire for "pecuniary advantage" had driven the companies to an "almost superhuman effort. . . .Gangs of men were worked day and night, and on the Sabbath the same as any other day. Time was too precious to incur delay in procuring the best material or performing the work in the best manner. The great primary object of the companies was money," concluded Morris, a fact that would "be made more manifest by time. The road by the charter, was to be completed by the first day of July, 1876 but its completion is announced in May, 1869! This may be American enterprise," he pondered, "or it may be American recklessness" (Morris 1869:5-6).

Regarding the Union Pacific road from the foot of the Promontory Mountains to the summit, Morris observed that this section of road was "the most difficult of construction, except the tunnels," of any portion he had examined (1869:6). He traced the course of the line, noting some of its problems:

For a mile and a half the ties, it is true, are virtually laid on the ground, but the road then passes through several sand banks, some comparatively small and some of formidable proportions, with intervening spaces of nearly level surface; thence it passes through rock excavations, one being some forty feet deep and a quarter of a mile long through the heaviest body of the mountain, overlooking Salt Lake; thence it sweeps around the mountain's side to its base, describing in its course a succession of short curves, so sharp indeed that an ascending and descending train would collide before either would be aware of the proximity of the other [1869:6].

Morris found the trestles to be "very frail and dangerous," stating that the Union Pacific planned "to fill up these ravines so as to have a solid road bed over them." He questioned whether the grade was actually 80 feet to the mile, thinking that "it must be much greater than this a part of the way." The "partly finished" Central Pacific's grade down the east slope appeared to Morris to be "still greater, and its curves sharper. The engineers evidently did not agree in their surveys," he surmised. He further criticized the rails at "56 pounds to the linear yard" as too light and thought that the ties were not large enough "to insure safety" (1869:6).

General problems that Morris found in all portions of the Union Pacific road that he examined included the following: insufficient ballast; the need for greater regularity in how ties were laid on the roadbed; and the use of untreated white pine for ties (processing included either "burnettizing or kyanizing") (1869:10-11). The use of white pine, however, reflected the limitation in the choice of available materials, and, while the profit motive no doubt at times had led railroad officials to cut corners and to push construction forward at too rapid a pace, there was no refuting that the transcontinental railroad had been completed more than six years ahead of schedule.

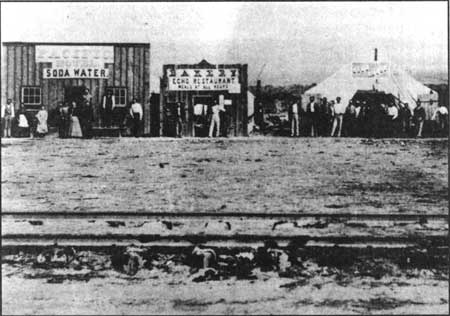

Photographs of Promontory Summit taken in 1869 show an assortment of establishments, such as the Pacific Hotel, and the Echo Bakery and Restaurant, which boasted "meals at all hours." These buildings, numbering around 30, were actually large canvas tents, some of which had wooden storefronts, lined up along a single street that ran parallel to the train tracks (Figure 15). A couple of weeks after the driving of the last spike, New York Tribune correspondent, Albert Richardson, described Promontory in this way: "It is bivouac without comfort, it is delay without rest. It is sun that scorches, and alkali dust that blinds. It is vile whiskey, vile cigars, petty gambling, and stale newspapers at twenty-five cents apiece. It would drive a morbid man to suicide. It is thirty tents upon the Great Sahara, sans trees, sans water, sans comfort, sans everything" (Bain 1999:653).

|

| Figure 15. Looking northwest to the tent city that developed north of the railroad tracks at Promontory Summit. Source: J.B. Salvias photo, 1869. |

During 1869, Promontory's saloons, cheap hotels and gambling businesses earned the place a rough reputation (Best 1969a:197). Customers included railroad construction workers who had stayed in the area and were waiting to receive their last pay (Anderson 1968:8). Englishman W. F. Rae, an early passenger through Promontory, recalled the gambling dens' practice of sending agents onto the trains to entice passengers to try their luck at the gambling table in Promontory. After typically stripping the passengers, many of them emigrants, of all their cash, the proprietors in a fit of charity would give them some of their money back to pay for the rest of their trip. "Although the small population of this place is composed for the most part of roughs and gamblers, with the admixture of a female element quite as obnoxious," explained Rae, "yet the peace is tolerably well kept on account of the awe felt for the railway officials. It is tacitly understood that open lawlessness or any serious disturbance would end in the clean sweep of the whole nest of scoundrels" (Rae 1871:185-186, 189-190).

In 1869, Crofutt's Transcontinental Guide described the journey from Blue Creek Station to Promontory:

Leaving the station, we cross Blue creek on a trestle bridge 300 feet long and 30 feet high. Thence by tortuous curves we wind around the heads of several little valleys, crossing them well against the hill side, by heavy fills. After passing some deep cutting and heavy work, we pass a trestle bridge 500 feet long, and 87 feet high. At and around this point the work is very heavy. Here we come close to the graded bed of the Central, which extends past Promontory to Ogden City.. . .Through more deep rock cuts and over heavy fills, we wind around Promontory Mountain until the [Great Salt] lake is lost to view. Up, up we go, the engine puffing and snorting with its arduous labors, until the summit is gained, and we arrive at the present terminus of the Union Pacific Railroad, Promontory Point [Summit] [1869:131].

Commenting on the source of water for Promontory at the time, Crofutt's guidebook explained that the "supply of water is obtained from a spring about four miles south of the road, one of the gulches of the Promontory Mountain[s]." The railroad brought water for its use from Indian Creek, also known as Kelton, as well as from other water stations along the line. Water trains ran daily. Commenting further on the agricultural potential of the area, the transcontinental guide observed that the "bench on which the station stands would doubtless produce vegetables or grain, if it could be irrigated, for the sandy soil is largely mixed with loam, d the bunch grass and sage-brush grow luxuriantly (Crofutt 1869:139). Given the difficulties in obtaining water, however, agricultural development involving irrigation proved unfeasible in the Promontory area.

On November 10, 1869, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific reached an agreement regarding the purchase of the UP's line between Promontory and Ogden, as the April 10, 1869 joint resolution in Congress had directed. For approximately $3 million, the Central Pacific bought 48-1/2 miles of UP track. During the course of negotiations, the Central Pacific threatened to build a separate track to Ogden if the Union Pacific would not accept its terms. In serious financial distress, the Union Pacific was not in a position to obtain a higher price, having originally asked for more than $4 million. As part of the settlement, the Central Pacific also agreed to lease the remaining 5 miles west of Odgen but this 999-year lease was not actually negotiated until June 13, 1875 (Best 1969a:67; Section on Terminus, Historical Catalogue, Union Pacific Historical Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1951:16, 20).

The April 10, 1869 resolution had also ordered the appointment of a commission to examine the condition of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, and to estimate the sums necessary to pay for any deficiencies in the roads. The goal was to ensure that the transcontinental railroad was "first-class," defined further as a road that "should be capable of transporting passengers and freight with rapidity, safety, and certainty — a road as good as the majority of those in the thickly settled States" (Letter of the Secretary of the Interior, May 23, 1870, 41st Congress, 2d session, Senate Executive Document 90:2).

Appointed to the commission were Hiram Walbridge, S. M. Fenton, C. B. Comstock, E. F. Winslow, and J. F. Boyd. They submitted their evaluation in a report dated October 30, 1869. They reviewed such specific construction features as: location, road-bed, tunnels, bridges, trestles, and culverts, snow sheds, track, sidings, ballast, station-houses, water stations, machine shops and engine-houses, equipment, and telegraph line. Minimal deficiencies were noted for the Central Pacific line. The modifications recommended for the CP line were limited to ballasting the track and widening the embankments. Echoing the earlier report of Isaac Morris, the commission noted a greater number of deficiencies, however, along the Union Pacific line. Because several of them were concentrated in the part of the line between Promontory and Ogden, the commission prepared a separate cost estimate for this short section. With regard to ballast used in the Promontory area, the commission found that, although a "considerable portion of the road is well ballasted with good material," still "quite a large amount" was needed to meet construction standards (Sen. Exec. Doc. 90:8).

Also requiring more work, according to the commission's evaluation, were the trestles near Promontory Summit: "Several of the high trestles between Blue Creek station and Promontory ought to be filled up at once. They were evidently intended as temporary expedients to gain time in opening the road" (Sen. Exec. Doc. 90:6). The report's cost estimate, designating all the work that needed to be done on the line between Promontory and Ogden, appeared as follows:

Estimates for Supplying Deficiencies, Union Pacific Railroad, Promontory to Ogden

| Ballasting track | $46,000 |

| Widening embankments | 6,400 |

| Filling high trestles between one thousand and seventy-sixth and one thousand and eighty-fifth miles, inclusive | $38,000 |

| Abutments and piers at Bear River bridge, in addition to materials on hand and work done | 5,000 |

| Abutments, Ogden River bridge, in addition to work done and materials on hand | 4,000 |

| Filling up and making permanent water-ways at forty-four short openings | ,000 |

| Filling up and making permanent water-ways at three larger openings | ,200 |

| Filling, putting in straining beam bridges and abutment, at three large trestles | 5,400 |

| Correcting construction and reducing grades to conform to accepted location between one thousand and eightieth and one thousand and eighty-fifth miles inclusive | 80,000 |

| TOTAL | $206,000 |

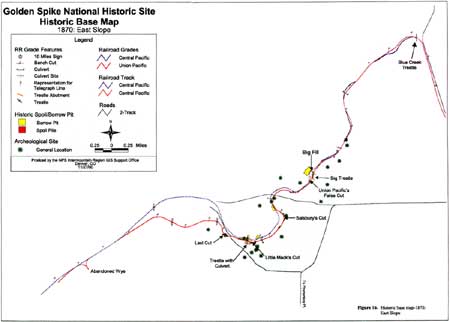

When the Central Pacific acquired the Union Pacific line, the company assumed the job of making these adjustments. The work resulted in the abandonment of some of the Union Pacific's line in order to relocate the track to the much better quality Central Pacific grade. The end result was a road that was some 1,200 feet longer between Promontory and Blue Creek. The track bypassed the UP trestles and ran instead on the solid fills constructed by the CP (Crofutt 1879: 132). East of the Big Fill, material from the redundant CP constructed grade was used to reconstruct the through grade so that the height and alignments of the various grade segments matched. The cost of the work greatly exceeded the estimates, totaling over $750,000 when completed (Gregory 1876:21; Section on Terminus, Historical Catalogue, Union Pacific Historical Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1951:17). [16] Figure 16 shows the conditions on the east slope in 1870, after the CP assumed control of the line between Promontory and Ogden and made changes to the alignment for both safety and ease of maintenance. (See Figure 13 to compare the differences between 1869 and 1870 alignment.)

|

| Figure 16. Historic Base Map—1870: East Slope. |

When Central Pacific took over the line between the summit and Ogden, it also became responsible for Promontory Station. In response to passengers' complaints, CP officials promptly evicted the proprietors of the tent city establishments and sent a special train to Promontory to take them as far as Corinne where they were summarily dropped. This ejection, coupled with the switch of the terminus to the station in Ogden, spelled the end of Promontory as a lively railroad stop (Best 1969a:138, 197).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr2h.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003