|

Golden Spike

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

CHAPTER 2:

SITE HISTORY (continued)

The Transcontinental Railroad and Promontory Station: 1870-1904

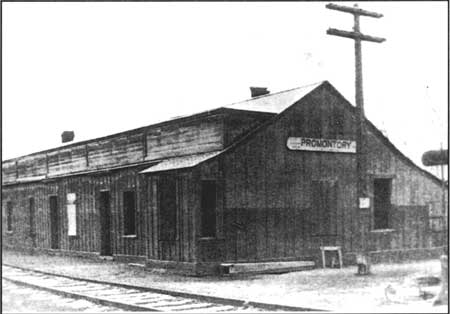

Rather than a burgeoning railroad town, then, Promontory Station became a "freighting town" and a maintenance station for the railroad. Buildings associated with its railroad functions included a freight depot from which freight was loaded onto wagons for transport to mining camps to the north and to other destinations. Other structures that served the railroad and railroad and train employees included a turntable, which had tracks running fanwise into a roundhouse built on a brick foundation. Estimates of the capacity of this roundhouse range from four to eight engines (Ayres 1982:107-109). To the south and west of the track were built a section house, tool sheds and bunk houses for workers, all painted a dark red at this point (Figure 17). Some of these buildings used cross-ties in their construction. A water tank, measuring 24 feet by 24 feet, stood near these structures (Ayres 1982:106, 108). [17] Tank cars delivered water here from the Bear River at Corinne. Water used at the Golden Hotel, described as "a more permanent frame building," was also pumped from these tank cars and stored in nearby cisterns. Water pipelines ran from the cisterns to the tracks. Promontory residents planted box elder trees — where water could reach them — to add a little green and shade to their surroundings, two of which have survived into the present (Anderson 1968:8; Owens 1974:7; Raymond and Fike 1981:22-27).

|

| Figure 17. Promontory ticket and telegraph office. Photo pre-dates 1900. Source: GOSP Historical Photo Collection, GOSP NHS. |

During the 1870s and 1880s, and for some time afterward, the Central Pacific continued to stop at Promontory for a short dinner break. T. G. Brown, proprietor of Promontory's Golden Hotel (Figure 18) as of the early 1890s, had handbills distributed on all the transcontinental trains advertising his "first-class meals, 50 cents — Don't fail to treat yourself to a first class meal at this celebrated point" (Ayres 1982:108, 113; Best 1969a:197). The Golden Hotel possibly also served as the passenger depot and post office as well as a home for the Brown family (Anderson 1968:8). Brown's daughter, Marion Woodward, recalled that her father operated a restaurant, which had a small store at one end (Ayres 1982:78, 113; copy of Woodward's remembrance available at Golden Site National Historic Site).

|

| Figure 18. The old Golden Hotel—used as the Houghton Store after 1909. Photo taken in 1947. Source: GOSP Historic Photo Collection, C-409, GOSP, NHS. |

By 1872, Crofutt's description of Promontory had changed, reflecting the reduction in activity there since the terminus had switched to Ogden. "The town was formerly composed of about 30 board and canvas buildings including several saloons and restaurants," the guidebook noted, "but now is almost entirely deserted" (1872:116). Also by 1872, passengers on the trains could look out their window to see a sign that read "Ten Miles of Track Laid in One Day, April 28th, 1869." This sign, located at a spot on the south side of the track roughly 4 miles west of Promontory Station, marked the east end of the portion of track where the Central Pacific workers had accomplished that unexcelled feat (Crofutt 1872:121).

Because of the steep slopes east and west of the station, nearly all trains coming through Promontory required the use of "helper engines." These engines met the trains either at Blue Creek or Rozel (Anderson 1968:8). In its 1876 issue, another transcontinental guidebook of the helper trains out of Blue Creek: "If we have a heavy train a helper engine is here awaiting our arrival, and will assist in pulling us up the hill to Promontory." Describing the route as it wound farther up the slope, the guide continued:

Between this and the next station, are some very heavy grades, short curves and deep rocky cuts, with fills across ravines. . . .Leaving this station [Blue Creek], we begin to climb around a curve and up the side of the Promontory Range. The old grade of the Union Pacific is crossed and recrossed in several places, and is only a short distance away [Williams 1876:163].

By 1870, the Central Pacific had altered the track between Blue Creek and Promontory Station. The 1874 issue of Crofutt's guidebook explained that the "track along here," climbing the slope out of Blue Creek, "has been recently changed, to avoid passing over several high trestle bridges built by the Union Pacific when they extended their track to Promontory" (Crofutt 1874:91). Gradually ascending to the summit from the east, The Pacific Tourist noted the "grand" view of Great Salt Lake, Corinne, Ogden, and the Wasatch Mountains. Traveling west out of Promontory, this guidebook pointed out that "a sugar-loaf peak rises on our right, and as we near it, the lake again comes into view, looking like a green meadow in the distance." Regarding Promontory Station, The Pacific Tourist observed that "its glory has departed, and its importance at this time, is chiefly historic," well known as it was "as the meeting of the two railroads." The guidebook lamented the fact, however, that, because the trains passed through Promontory at night, passengers could not "catch even a glimpse" of the historic junction site (Williams 1876:164, 166).

In 1876, the House of Representatives passed a resolution requesting a careful and exact survey of the distances on the Union Pacific and Central Pacific lines. Captain James F. Gregory with the Army Corps of Engineers was in charge of measuring the distance of the Central Pacific Railroad between Ogden and Battle Mountain, Nevada. Specific measurements that applied to the Promontory Summit area show changes in the line since 1869 and identify two places where "old and new grades" crossed. On the east slope the "eastern junction of [the] old and new grades" was at a point 47 miles and 2089.3 feet west of Ogden. Still on the east slope, at a distance of not quite 5 miles from the previous meeting of the grades, the "western junction of [the] old and new grades" was found to be 52 miles, 1187.8 feet west of Odgen. Promontory depot was 53 miles, 443.8 feet west of Ogden. "Promontory, switch 1" was located at a point east of the depot, at a distance of 52 miles, 4007.8 feet from Ogden. Just 264 feet west of the depot was another switch, at the 53-mile, 707.8-feet mark. The "original junction" of the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific was spotted at a distance of 53 miles, 892.8 feet west of Ogden. Just 415 feet west of there was a third switch, located at a point 53 miles and 1307.8 feet west of Ogden. A fourth switch was spotted at a point 1770 feet farther west. Between the Blue Creek depot and the Rozel water tank, the surveyors identified the locations of 10 culverts and spotted the sign-post that indicated the eastern end of the 10-mile-day at a point 56 miles, 4115.8 feet west of Odgen (Gregory, 1876, in House Executive Document 38, 44th Congress, 2d session, Feb. 1, 1877:23). [18]

Specifics concerning grades and curves on the line are as follows: The ascent of the west slope required a grade of 1.62 percent, or 1.62 feet of rise over a distance of 100 feet. On the steeper east side, the grade was "a grueling" 2.21 percent. The entire line, from Ogden to Lucin, included 31 miles of track that lay on curves less than 6 degrees; another 2 miles contained curves greater than 6 degrees; and some curves over a short stretch of the line measured 10 degrees. (A curve of 3 degrees on a main line is considered a sharp curve; a curve of 6 degrees is considered very sharp.) The speed of all trains along the route was restricted to 15 miles per hour (Strack 1997:49).

By the early 1880s, ranching was becoming an increasingly important aspect of the Promontory area's economy. Charles Crocker, one of the Central Pacific's Big Four, had been principally involved in organizing a huge livestock operation, the Golden State Land and Cattle Company (which later became the Bar-M). Crocker also oversaw the building of a large mansion that served as headquarters of the livestock company and as a place to entertain guests of the railroad. Located about a mile north and visible from Promontory Station, the "Big House" contained eight bedrooms, each with a private bath. Water from nearby springs was piped into the house. Ranch workers stayed in bunk houses with large dining rooms. Chinese cooks were hired to prepare the food for both ranch hands and guests (Anderson 1968:9).

Crocker ran as many as 75,000 cattle on open range that extended eastward from the Nevada border to the Bear River and northward through western Box Elder County, Utah and into southern Idaho. During the fierce winter of 1888, when so many ranchers throughout the West were wiped out, Crocker's outfit lost approximately 10,000 head. Around 1900, the "Big House " was moved to another Bar-M ranch, the Sorenson Ranch located in Howell, Utah. Other ranches in the Promontory area, many of which were eventually bought by Bar-M, included the Davis ranch, Connor Springs ranch, Dilly's ranch, and Hillside ranch. (Anderson 1968:9).

By the 1880s, many of the key Central Pacific officers had also incorporated the Southern Pacific Railroad Company in order to build a railroad from San Francisco to San Diego and to other points to the east. In business since late 1865, the Southern Pacific system was initially leased to the Central Pacific. In the mid-i 880s this lease arrangement was reversed. During a six-week period between late September and early November, 1884, officials of both companies held a series of meetings in New York City to agree on the terms of a new leasing agreement. On February 17, 1885, the lease was signed. The Southern Pacific Company, newly organized and incorporated in Kentucky, agreed to lease the Central Pacific railroad for a term of 99 years dating from April 1, 1885, and to pay an annual rent that could vary from $1.2 million to $3.6 million, depending on the earnings of the Central Pacific (Daggett 1922:148-151; Raymond and Fike 1981:22; Section on Terminus, Historical Catalogue, Union Pacific Historical Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1951:26; Strack 1997:45-46).

Remaining an entirely separate corporate entity until 1959 when it formally merged with Southern Pacific, the Central Pacific underwent a reorganization in 1899 — the timing of which reflected the coming due of the 30-year bonds issued by the federal government as part of the railroad's subsidy. After the reorganization, the Central Pacific was more able to attend to improving its railroad. Of significant concern was the objective of eliminating the route over Promontory Summit, which had become "an operational bottleneck," because the sharp ascent over the summit added both time and distance to the route. Passenger trains typically had to be divided into three sections, each of which required a helper train in order to get to the summit. The "bottleneck" moreover added expense: the frequent use of helper engines cost the railroad some $1,500 per day (Mann 1969:129; Strack 1997:47).

Planning for what would be called the Lucin Cutoff began in November, 1899. At the time, six million tons of railroad traffic — ten trains a day, each consisting of thirty-three 50-ton cars — was annually passing over Promontory Summit. The cutoff over the Bear River and Spring Bay arms of Great Salt Lake shaved 43 miles off the trip between Nevada and Ogden. In transit time, it saved an average of 24 hours. On November 13, 1903, the last rail of the Lucin Cutoff was laid. Several months later, on March 8, 1904, freight trains began taking the cutoff route, but because some parts of the fill into the lake were still settling, passenger trains continued to pass through Promontory until September 18, 1904. Finally, on January 1, 1905, the Lucin Cutoff was officially opened (Strack 1997:47-48). Subsequently, the frequency of trains through Promontory Station gradually diminished and the economy of the area increasingly depended on agriculture.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/gosp/clr/clr2i.htm

Last Updated: 27-Jul-2003