|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 1 A Preliminary Survey of Fauna Relations in National Parks |

|

ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TYPES OF WILD-LIFE PROBLEMS THEIR CAUSES AND TREATMENT

THE BASIC CAUSES OF PRESENT FAUNAL MALADJUSTMENTS

When a roster of typical wild-life problems from the whole national park system was assembled, a very wide range of maladjustments was revealed. A systematic analysis was made to trace each problem back to the basic disturbance which brought it about. For if any common denominators could be found, that knowledge would be a key to devising a betterment plan. Early in the work it became apparent that the fundamental causes were relatively few. If a number of problems could be traced to a common origin, more rapid and orderly progress in wild-life administration would be possible than if each problem were dealt with as an isolated instance.

From this analytical study the conclusion was reached that present complications in the status and environmental relations of park animals have come from these three general sources:

1. Adverse early influences – The present unsatisfactory status of an animal may be the result of a destructive force which itself is no longer active. These are problems caused by early influences. It is convenient to think of them as the problems of historical origin. Problems of this class fall into two groups, according to whether the influence was one which destroyed these fauna directly or one which operated indirectly by altering some part of the environment upon which the fauna depends.

2. Failure of parks as independent biological units. – A park is an artificial unit, not an independent biological unit with natural boundaries (unless it happens to be an island). The boundaries, as drawn, frequently fail to include terrain which is vital to the park animals during some part of their annual cycles. The smaller the total area of a park the more its animal life may be endangered by external influences. Problems caused by the failure of parks as biological entities have to do with their geographical aspects, such as size and boundary location. It is easy to think of them as problems of geographical origin. They logically fall into two groups, according to whether they have come from failure to include all habitats required by park animals or from external influences which do not find the boundaries a natural barrier.

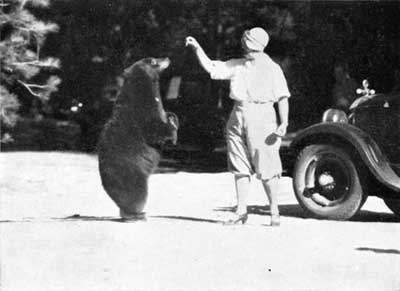

3. Conflict between man and animal in the park. – Troublesome situations inevitably arise when men and certain animals with conflicting interests try to occupy the same places at the same time. These complications come in spite of the human ideal that the wild life of the parks shall remain in a primitive state unmodified by civilization. Disturbances of this origin constitute the third class, the problems caused by conflict between man and animal through joint occupancy of the park areas. For brevity's sake they may be designated as problems of competitive origin. And once more it is profitable to make two divisions, this time according to whether problems are due to injury of man by the animals or due to man's occupation of the area affecting the fauna adversely.

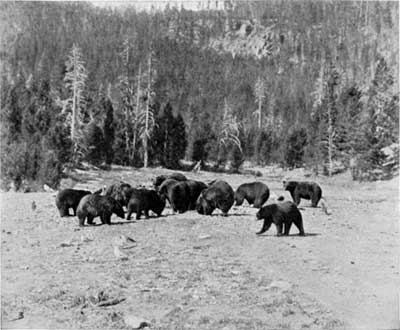

FIGURE 9. – Occasionally the interests of men and animals conflict. A bear profited in this foray to the extent of one roast of lamb. Photograph taken September 11, 1929, at Canyon Lodge, Yellowstone. Wild Life Survey No. 452 |

These three basic causes are responsible for the multitude of problems which must be solved with at least fair success if the faunal resource of the national parks is to be conserved.

The administrative measures invoked in every instance must he analysis gaged by accurate analysis of the causative factors which bred the problem. This is important. It is the key to proper practice in the program of wild-life administration upon which the parks have unavoidably embarked. In the end the Service either will be praised for intelligently conserving the last fragments of primitive America or condemned for failure to hold to the real purpose by shooting clear over the mark and practicing game farming instead.

The rigors of civilization have injured the fauna of the country as a whole. In a national park the damage can not be undone by policing a boundary line. This is protection and it is necessary, but it does not correct conditions already operative within the park. These must be sought out where they are doing damage and dealt with there. This is management, and the danger that it may be overdone is not sufficient reason for doing nothing.

Recognition that there are wild-life problems is admission that unnatural, man-made conditions exist. Therefore, there can be no logical objection to further interference by man to correct those conditions and restore the natural state. But due care must be taken that management does not create an even more artificial condition in place of the one it would correct.

If each problem is carefully analyzed as to its cause, and the type of management appropriate to problems caused in that way is then applied, management will not destroy its own purpose. Admittedly, the tool is a dangerously sharp one to use in a national park. That is why it must be handled within skill in biological engineering, a science which itself is in its infancy.

It is important in every case that the hand of interference should not be exercised beyond the point that is necessary to do the work. In some instances if the situation responsible for the maladjustment of a species can be corrected, that bird ear mammal will come back to its former status. Failing this, additional measures may be temporarily necessary to help it recuperate its strength. But where the basic disturbance can not be eliminated, management to counteract the evil effects may have to be instituted to continue so long as the harmful influence continues.

All of the problems which the survey has encountered to date are believed to be of historical, geographical, or competitive origin. The following outline lists major types of problems in each of these causative groups.

TYPE PROBLEMS LISTED BY CAUSE

| CAUSE | PROBLEM | |

|---|---|---|

| I. Earlier influences (historical) | ||

| a. Operating directly ------ |

1. To re-establish an extirpated species. 2. Treatment of a species reduced to danger point. 3. To restore a depleted habitat. | |

| b. Operating indirectly ----- | 4. Treatment of a species become unnaturally abundant. | |

| II. Failure of parks as independent biotic units (geographical) | ||

| a. Lack of complete animal habitat in park -- | 5. Lack of winter range. | |

| b. Encroachment of external influence ------ |

6. Reduction of park animals black-listed outside. 7. Invasion of exotics into the park. 8. Dilution of native stocks by hybridization. 9. Exposure of native animals to diseases and influences of alien faunas. | |

| III. Conflict between man and animal within the parks (competitive) | ||

| a. Animals interfering with man ------ |

10. Unusual damage to landscaping. 11. Conflicts with fish culture. 12. Animal injury to life or property. | |

| b. Human developments harmful to wild life -- |

13. Disturbance in development centers. 14. Effects of pasturing saddle horses. 15. Disturbances on breeding grounds. 16. Altered status because of manner of presentation. |

The scope of this report prevents discussing at length every problem encountered. Consequently the plan has been adopted of discussing the essential elements of each type of problem listed above and illustrating each with one or more examples treated in detail. These examples will serve as type problems to which others resulting from similar causes can be referred for comparison and study. Then in later sections dealing with the vertebrate life of each park as a unit, only those problems on which the survey has accumulated special data have been accorded more than outline treatment.

Where it seemed that more than one of the major causes entered into a certain problem, close inspection revealed that one of them was dominant in producing the present situation. These have been handled by allocation under their dominant cause.

The type problems given in the next three sections are arranged in accordance with the foregoing outline. They have been numbered to conform with the Arabic numerals in the outline merely to facilitate reference and to further emphasize the relation of problem to cause.

PROBLEMS OF HISTORICAL ORIGIN

THE RESULTS OF EARLIER INFLUENCES

All depending upon the history of development of the region, the fauna of a park at the time of establishment was either much the same as it had been originally or it was greatly altered. The scheme of wild-life administration should meet the latter condition by corrective measures. Maladjustments caused by factors which have been eliminated from the park area will not necessarily correct themselves because these original causes are no longer operative. Where the status of species which have been adversely affected continues without showing improvement for a number of years after full protection has been established, management should be applied.

CONDITIONS CAUSED BY DIRECT EFFECT OF EARLY INFLUENCES

The status of wild life was impaired directly and immediately where animal populations were decimated by trapping, shooting, or poisoning. Some species were actually exterminated from the areas before they became parks. Others had been reduced to small numbers and recuperation has not resulted from park protection. Drains on a species from natural causes which are not ordinarily fatal because of an ample breeding stock may be overwhelming when it has been reduced to a few mated pairs per unit area.

TO REESTABLISH AN EXTIRPATED SPECIES (1)

Restoration of an animal which has been exterminated is desirable not only because it will bring back that species itself, but because it will fill once more the niche that was deserted, and so help to restore the life of the park to its primitive dynamic balance. If the extirpated species is still present in the region, reoccupation of the park by natural spread should be encouraged. This is the best answer from the standpoint of expense and likelihood of lasting success. If on the other hand, there are natural or artificial barriers in between the park and the present occupied area, restocking must be the answer. If the animal is decreasing everywhere, this step must be taken promptly.

Thus the procedure adopted for meeting the individual problem will be largely determined by the status of the animal outside the park, as is illustrated in the following examples:

Grizzly bears in Sequoia. – The grizzlies of California are extinct. The suggestion has been made a number of times that replacement be made with a Rocky Mountain grizzly. This would be such an obvious mistake that it has never been seriously considered, yet in other instances of this same kind the incongruity might be just as great though not so immediately apparent. If an animal is extinct, the situation is beyond remedy. Attempt to replace the original with a related form would merely serve to create a new problem, the introduction of an exotic with different characteristics and, more especially, different ecological requirements than its extinct relative.

Mountain sheep in Yosemite. – The Sierra Nevada mountain sheep (Ovis canadensis sierrae) disappeared from Yosemite before the close of last century. Old horns and skulls are still found about high cliffs. There is a living remnant of this bighorn in the southern Sierra near Mount Whitney, where it is reported to be slowly increasing under protection. Two other related subspecies are the Lava Beds bighorn to the north, which is probably extinct, and the Nelson bighorn, which is still extant on some nearby desert mountains to the south.

Many have already expressed a wish to see Yosemite National Park restocked with mountain sheep, there being even some indication that private support might be forthcoming for such a project. The waiting policy adopted by the Service is the only justifiable course for the present. So long as the Sierra Nevada form still exists, it is the only source which can even be considered for reintroduction purposes. A gradual return of the southern remnant is the ideal solution, and there is a fighting chance that this will take place if it continues to increase and reoccupies its range northward along the crest of the mountains. Continued heavy grazing by domestic sheep between Yosemite and Mount Whitney will be a serious obstacle here.

Even though natural reestablishment should be considered too remote a possibility, waiting would still be a necessity for practical reasons. The southern band is still small and the sheep are rarely seen. They should not be disturbed; but if they were, success in capturing the necessary number and transporting them to Yosemite would be very unlikely. It would not pay to release such costly animals as these would be near the crest of the mountains. The park unfortunately does not include the east slope, which is the habitat preferred by the sheep. They are particularly dependent on this side during the period of heavy snow, and would be without the benefit of park protection at such times.

To sum up, the conclusions in this problem are: Return of the mountain sheep to Yosemite should be planned for, because the native form is still in existence; the procedure indicated by the elements of the case is to do nothing now except to watch the Mount Whitney sheep until either they work back naturally, or, failing that, become sufficiently abundant for a restocking experiment to have a chance of Success.

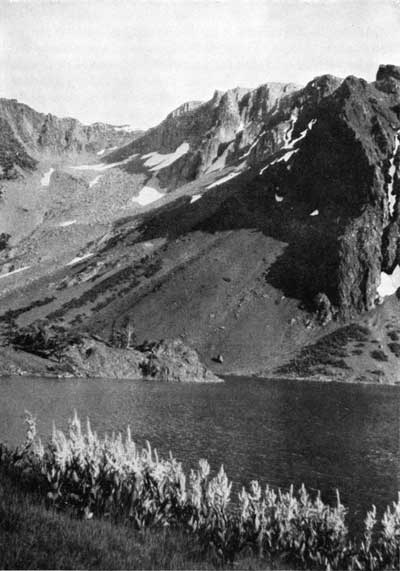

FIGURE 10. – Mount Dana. The eastern slope of the range, now outside Yosemite boundaries, would be needed by mountain sheep in winter. Photograph taken July 30, 1929, at Tioga Pass, California. Wild Life Survey No. 296 |

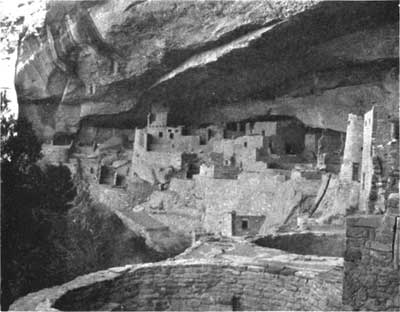

Wild turkey in Mesa Verde. – In the foregoing example the return of the mountain sheep to Yosemite is shown to be desirable, providing it can be accomplished under the proper conditions. Let us examine a second case – one in which the basic action itself is in question.

The problem is: Should the Merriam Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo merriami) of the Southwest be placed in Mesa Verde National Park ?

The Cliff Dwellers kept turkeys confined in the caves behind their dwellings. Turkey-bone implements and pieces of turkey-feather robes have been recovered, as well as many other evidences that the wild turkey was present and was an essential part of the Cliff Dwellers' economic, and possibly religious, life. There are no definite records or indications of the presence of turkeys on the mesa to-day. It would be of unusual interest and of educational value if these wonderful birds were occasionally seen, or, at least were known to be present, hidden in the forest and canyons of the mesa. In the thoughts of the visitor, these birds would be as a far cry back to that earlier life and culture, a symbol to link him more closely to that civilization as a reality. Their presence would lend a further charm and color to the wild life of the mesa to-day. But there are other considerations.

Is this the native habitat of the wild turkey ? "It is significant that by choice we find them in or near the yellow-pine type and always where living water – springs or streams – is available. Nowhere, in the memory of the oldest citizens of the State, have turkeys been resident where pine was not in evidence. If for no other reason, the adult birds seem to insistently choose pine trees in which to roost."7 There is almost no yellow pine on the mesa, and water is very scarce.

Did turkeys ever exist here naturally, or were they brought here in a semidomesticated state by the Cliff Dwellers ? If they were brought here, from where did they come ? Probably the nearest representatives of the Merriam turkey are those found in the Chusca Mountains between Arizona and New Mexico, north of Gallup. However, they are in an extensive yellow-pine country, which is their native habitat. Since they are found so close to Mesa Verde, it would not be surprising to find that they were at one time native to the mesa, except for the scarcity of yellow pine and water.

The following note on the wild life of the Chusca Mountains region is given by Vernon Bailey: "The Navajo Indians in their religious reverence for feathered spirits have made their great reservation to some extent a bird preserve. Ducks are unmolested in the lakes and doubtless breed there in considerable numbers. Wild turkeys have held their own unusually well, but have suffered somewhat from hunting by outsiders and Christianized Indians."8

Were turkeys left here after the Cliff Dwellers departed ? If so, what has become of them ?

If turkeys were not native to the mesa, would it not be confusing the whole significance of their part in Mesa Verde culture to place them there, and give the impression that they were native to the mesa? The significance of a visit to Mesa Verde is that it acquaints one with an earlier civilization through the actual remnants of that civilization, and it shows how that civilization was modified by, and adapted to, its particular environment. If we introduce an alien factor into the immediate setting, we are destroying the significance of the whole complex relationship between culture and environment.

These thoughts are not given to oppose the reintroduction of wild turkeys into this park. They are given simply as a preliminary analysis of the complexity of such a problem, and as an indication of some of the interactive factors which have to be considered before there can be a proper decision.

Once the desirability of reintroducing an exterminated species has been demonstrated, there are the practical problems to be worked out in the field, such as:

(a) Where the nearest representative of the species may be found.

(b) Practical means of securing pairs for reintroduction.

(c) The matter of cost.

(d) Practical measures, if necessary, for temporarily protecting the new stock until it establishes itself.

7 Wild Life of New Mexico, by Ligon, J. Stokley. State Game Commission, Department of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, N. Mex., 1927, p. 113.

8 Life Zones and Crop Zones of New Mexico, by Bailey, Vernon. North American Fauna, No. 35, 1913, p. 61.

TREATMENT OF A SPECIES REDUCED TO DANGER POINT (2)

In discussing the problem of a species whose numbers have been reduced to the danger line by the pioneer depredations of man, it is admitted that possibly nothing can be done to bring that animal back to its former status. Yet even this knowledge can not be had without first making a thorough investigation of the question, including, perhaps, experiment with some betterment measures. On the other hand, many species might be brought back if their plights and all the governing factors were sufficiently understood. A temporary program of special protection to bring about recuperation might include securing greater immunity for the young against enemies on the breeding grounds, or augmenting the food supply at a critical period, or some other measure, depending entirely, of course, on the individual circumstances of the case. In any event, every precaution should be taken against endangering the status of any other species while trying to help one; and, always, the special protection must be discontinued just as soon as the species is out of danger.

Trumpeter swan in Yellowstone. – This is perhaps the best example for this type of problem, not only because the number of trumpeter swans in the Yellowstone region was reduced to a few birds but because these represent the entire known breeding stock in the United States.

Though the trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator) and the whistling swan (Cygnus columbianus) are so much alike in appearance as to be almost indistinguishable in the field, the first has all but succumbed, while the latter continues to flourish. Comparison of the two forms is valuable in analyzing the present problem.

The whistling swan bred mainly north of the Arctic Circle, its nesting grounds unaffected by civilization. The trumpeter swan bred in Canada and the great interior valley of the United States, where it was subject to every adverse influence, even to the draining of many of the small breeding lakes.

As winter visitants in the south the whistlers were very shy, so that few were taken by gunners. They came down along the coasts and kept to open waters. The trumpeters, on the other hand, were much less wary, frequenting smaller bodies of water and coming in close to the hunters' blinds.

A whistler might weigh 18 pounds; a large trumpeter, 33. Consequently, the trumpeters made more desirable skins and must have been at a premium in the great swan trade of the Hudson Bay Fur Co., which destroyed the bulk of these birds, even to the northern part of their range, long before permanent settlement came along to do the rest.

As a result of all these influences the trumpeter swan nearly passed from the picture. Its present status is as follows:

In Canada : For conservation reasons, the Canadian Government keeps its data on this species a secret. It is known that a few winter in southern British Columbia, but their breeding grounds have not been discovered. They are believed to be in the northern part of the Province, where, if any colony is found out by Indian or prospector, it is sure to be destroyed.

in the United States : Though the trumpeter may possibly occur south of the international boundary in migration, it is gone as a breeding bird except in the immediate Yellowstone region. All recent nesting records are within the park except for two stations – Jackson Lake, Wyo., and Red Rock Lake, Mont.

The latest breeding census made by the survey party in 1931 showed 5 breeding pairs and 10 birds not breeding. The 5 nests are known to have hatched 18 cygnets, of which 5 were certain losses in the summer, leaving a potential crop of 13. Probably there were further reductions before flying time in late fall, and still others before the winter was over. What this means for perpetuation becomes more significant when one takes into account that breeding age is not attained until the fourth or fifth year.

In captivity : Mr. F. E. Blaauw, of Holland, secured five trumpeters over 30 years ago. Though he has been successful with them, his present stock consists of only 10, of which 5 are immature. In the past few years 12 of Blaauw's birds went to the Kellogg Bird Sanctuary at Battle Creek, Mich. It has not been ascertained that these have bred there.

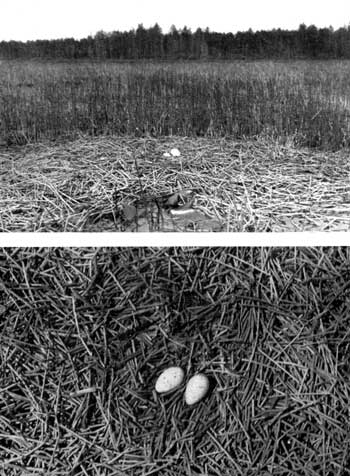

FIGURE 11. – Only the watchfulness of the parents deprived ravens of a feast on the four large eggs of this trumpeter swan nest. Photograph taken May 30, 1931, at Trumpeter Lake, Yellowstone, by G. M. Wright. Wild Life Survey No. 2353 |

So much for the general picture. What can be done to perpetuate and increase the trumpeter swan in Yellowstone Park ? Report was received in 1929 that a pair on a small lake in the Lamar Valley had failed to raise any young in the four or five summers they had been observed. In the spring of 1930 the survey party found two nests – the one mentioned above and a second on Mirror Plateau. Each clutch was composed of six eggs. Yet there was but one living cygnet by late autumn.

Suspicion fell upon a number of possible enemies, but only one was convicted. A raven broke an egg in the nest on Mirror Plateau and tried to fly off with the embryo. There were frequent raids by the ravens at the other nest, but they were successfully resisted.

Potential enemies of the cygnets were the coyote, otter, horned owl, eagle, and possibly even the badger. Coyote tracks were abundant around the margins of the lakes, and badgers lived all around. The entire swan families frequently took to the land to feed or to cross to near-by ponds, and they would be easy prey at such times. When the cygnets were small, an otter visited the Lamar Lake. Coots within 6 or 8 feet of the otter showed curiosity, but no fear, and were ignored in return. Neither was the swan family hurt. In the fall, when the cygnets were disappearing one by one, an otter family came to stay in the lake for a time. Coot and ruddy duck remains were found in the feces, but no sign of a cygnet. The otters were not proved guilty.

One night in the following summer a member of the party slept at the very edge of the lake so that he might hear any unusual sound. In the morning one cygnet was missing. Horned owls were in the air that night, but this was not hanging evidence.

This season was a dry one. Several lakes reputed to harbor swans were found to be so low that even beaver houses were left dry. This suggests that in certain years swans attempting to nest on shallow waters may have their lakes vanish, or at least shrink until the nests are accessible to land enemies.

FIGURE 12. – Shallow lake in the Bechler district in a dry season. Trumpeter swan nests may suffer the same fate as this beaver house. Photograph taken July 24, 1931, in Yellowstone, by G. M. Wright. Wild Life Survey No. 2292 |

Winter status of the trumpeters was an open question because their movements after they were frozen out of the home lakes were not known. But during a cold spell early in 1932, 28 swans appeared on thermally warmed waters in the park. At the end of February the count totaled 41. This was good news, for, if the Yellowstone birds remain in or near the park in winter as well as summer, the hope of saving them is greatly increased.

The present indication is that the swans are at least hanging on. This permits of a little more time for intensive research to discover the critical factors during the periods of incubation, of raising the cygnets, and of absence from the breeding ponds in winter.

Many protective measures have been suggested, but it seems inadvisable to try much without better knowledge of the basic facts unless a tendency to further decrease becomes apparent. That would be an emergency justifying drastic action, such as removing all suspects from around the nesting lakes or raising a portion of the cygnets in semicaptivity where conditions could be definitely controlled. Measures in addition to the above which have been proposed are : Fencing coyote-proof lanes for swan travel between lakes, ranger detail to keep ravens cleared out during the incubation period, prohibition of entry to the breeding lakes by park visitors, enlistment of public support to wipe out the vandalism which is known to affect the swans when they are outside the park, and other suggestions.

The partial conclusions from investigations made to date are that whereas the trumpeter swan was decimated as the result of civilization's influence, and whereas the species may not be able to come back under ordinary park protection, it is desirable in consequence that there should be a program of careful study with a view to resorting to intensive management if further developments prove the necessity. This does not fail to recognize that low survival rate of cygnets may be normal for this species, inasmuch as the swan is long-lived and has relatively few natural enemies when full grown. But when the trumpeter is nearly extinct, it is important for as many cygnets as possible to survive, at least until such time as the breeding stock is restored to numerical safety. It is a case where special protection is amply justified as a temporary measure.

FIGURE 13. – Adult trumpeters and six cygnets (one hidden in tules). The grown birds are powerful and capable of protecting their young in the water, but all are at a disadvantage on land. (Note rubber boat used by Survey in distance.). Photograph taken June 20, 1930, at Lamar River, Yellowstone. Wild Life Survey No. 880 |

FIGURE 14. – Two trumpeter swan cygnets from the same brood. Do young of the gray phase have a better chance of escaping enemies than those of the white phase ? Photograph taken June 12, 1931, at Trumpeter Lake, Yellowstone by G. M. Wright. Wild Life Survey No. 2268 |

CONDITIONS CAUSED BY EARLY INFLUENCES OPERATING INDIRECTLY

Major influences responsible for injuring wild life indirectly were stock raising, agriculture, and lumbering. These human activities which affected the fauna adversely through altering essential elements in its environment have left behind them problems of very complicated nature. The ramifications of the upsets they caused are great, and, consequently, difficult to disentangle. One of the worst influences, that of grazing, has not yet been completely eliminated. That is an objective which must be consummated at the earliest possible date. From the wild-life standpoint, an area is not a national park in fact until all domestic stock is permanently removed. The policy of not renewing permits when they expire seems to be the fairest method of meeting this situation.

But with the above exception, the original influences have been removed from the parks proper. The first step, then, in solving the problems which they have left behind them is to restore the altered environment to its original state, which was known to have been favorable to the species in question. Because this restoration may take a long time to accomplish, the species suffering may have to be sustained by a temporary program of assistance. If it is a case of a depleted range, the range itself may have to be temporarily protected against the animal until its grazing capacity is restored.

TO RESTORE A DEPLETED HABITAT (3)

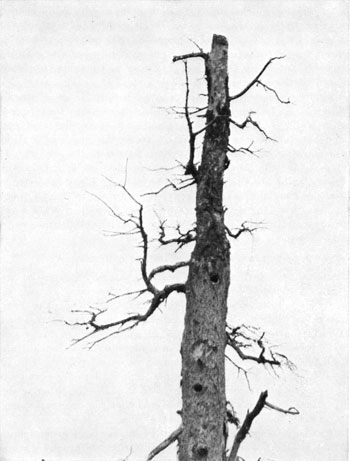

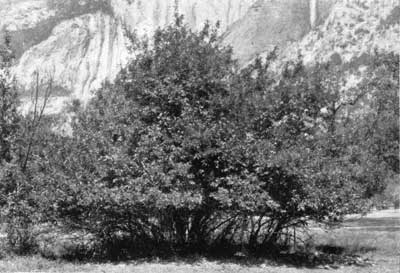

It is hardly necessary to point out the close relationship between animal life and food supply. This refers not only to the grazing and browsing areas of the ungulates, but includes the food supply of every type of animal life; i. e., if rodents and other forms of marten food have been destroyed, the marten's range is just as truly depleted as that of the elk when palatable herbage and browse are gone. And again, if wild life is managed along the all-too-thrifty and enterprising lines of a game farm, the range of the scavengers is apt to be empty. It is necessary that the trees be left to accumulate dead limbs and rot in the trunks; that the forest floor become littered; and that the wild life be left to prey upon itself in order that the range may not be destroyed for any species and that vigorous, healthy animals may be left in every niche.

Turning to the most obvious and important type of depleted food supply due to early conditions, we note especially that almost every range suitable for big game was overgrazed by sheep, cattle, and horses before 1900. In order to get some idea of the condition of the grassland ranges in their primitive condition, even when the great herds of buffalo and antelope roamed them, the following account from Coronado's explorations in 1540 through the territory now embracing the Southwest and prairie States is enlightening : "Who could believe. that 1,000 horses and 500 of our cows and more than 5,000 rams and ewes and more than 1,500 friendly Indians and servants in traveling over these plains would leave no more trace where they had passed than if nothing had been there – nothing – so that it was necessary to make piles of bones and cow dung now and then so that the rear guard could follow the army."9 There was rank growth of the tall grasses then, whereas now the tall grasses are mostly gone, and even the short grasses are gone from many parts of the western range. In their places have come the unpalatable species that inevitably follow overgrazing. So that even where a range seems to be well covered, it may be with the unpalatable and undesirable types which leave little food for the game. This is the condition which exists in nearly all our parks to some extent, and especially in the Southwest parks and monuments.

Deer range in Zion Canyon. – In Zion National Park, the story as told by Ranger Harold Russell is essentially this : In 1909-10 about 3,000,000 board feet of yellow pine were logged off the east-rim country. Young pines are coming back, but the forest is replacing very slowly, as it does everywhere in this arid country. Mr. Russell said that forage conditions within the park are much better than they were formerly. The region had been grazed for 40 years before he saw it, and he was first at Zion in 1902. In the early days, settlers farmed the river bottom below Zion and up on the canyon floor. Owing to erosion started by overgrazing on the headwaters of the Virgin River, floods washed away the farm lands below, and they had to be deserted. Livestock, however, still ranged in the canyon. In 1915 a hard winter found the animals without feed. Every bit of forage was gone from the canyon. The settlers were forced to come up into Zion Canyon and cut down the cottonwoods so that their stock could eat the bark.

It is evident that conditions in Zion are much improved. Unfortunately, the watershed above the canyon is still badly overgrazed, and erosion and floods are taking their toll from the valley floor each season. But in the park itself, a thorough investigation of the range – degree of palatable forage, carrying capacity, etc. – needs to be worked out before large numbers of deer are allowed to come back. The same is true of Bryce, south rim of the Grand Canyon, the Indian reservations, the Guadalupe Mountains by Carlsbad, and of many of the winter-forage areas in the Rocky Mountain parks. Such areas should be lightly grazed for a number of years to give them chance to recover. Especially should horses be kept off these areas during the summer time in order to allow them to produce winter feed. The tendency to restore the ungulates at the expense of range and other forms of animal life should be guarded against for a number of years, thereby giving the range time to recover its normal carrying capacity. Unless this is done, the damage is apt to be permanent.

9 Castaneda's narration, "Relacion," Winship translation. Fourteenth Annual Report, Bureau of Ethnology, 1892-93.

ABNORMAL ANIMAL POPULATIONS DUE TO EARLIER REMOVAL OF NATURAL CONTROLS (4)

Problems of this type that trace back to pre-park conditions are usually found to have been by-products of the stock-raising industry. Predatory animals, which normally controlled the undue increase of the wild ungulates, were eliminated to protect stock on the ranges and incidentally to provide more game for hunting. So long as they were open areas, the gun more than took the place of the predators, but the situation was reversed when they became parks. The large game increased without check until it further destroyed ranges which had already been impoverished by sheep and cattle. Worse than that, this unusual protection not only permitted the healthy animals to survive but also failed to take off the diseased and unfit, leaving them to reproduce and deteriorate the breeding stock. The local situation produced by an abnormal density of impoverished ungulates in conjunction with forage of greatly subnormal density and quality is like a bad fire hazard. All it requires is a bad season to precipitate a calamity. Only in one case the critical factor is a dry summer, in the other it is a snowy winter. In general, the solution of problems of this type is to be sought in the restoration of the natural control factor in environment. Yet in many instances this may take place so slowly that artificial control may have to be substituted as a temporary measure. Shooting for sport is unsatisfactory because it is selective of the finest specimens instead of the poor ones which, by rights, should be removed first.

Mule deer on north rim of the Grand Canyon. – This is a park question but, in its larger aspect, it is the Kaibab deer problem, which is so well known that it only needs to be mentioned here to serve as an excellent illustration.

Mule deer in Yosemite Valley. – Because the mountain lion was gone and other conditions altered, deer increased until the once famous wild-flower show on the floor of Yosemite Valley became a thing of memory, and even the brush was threatened with destruction. Deer were so common and so goat-like – having no need to be alert, and hence losing their charming wild behavior – that their interest to the visitor was greatly lessened. Crippled and diseased individuals which do not last long under natural conditions dragged around and added to the ugliness of the picture.

FIGURE 15. – Deer are particularly fond of the flower beds of Evening Primrose (Oenothera hookeri). They did not overlook one in these three clumps, though the plants grew inside a supposedly deer-proof fence. Photograph taken July 20, 1929, in Yosemite Valley. Wild Life Survey No. 186 |

The first protective move made was to fence a few acres around the Ahwahnee grounds to preserve the plant life. This was not really compatible with national-park ideals.

Physically incapacitated deer were dispatched, and this helped one aspect of the problem.

A third measure was tried with success. Deer had been practically exterminated from the Tuolumne watershed in a successful campaign to stamp out hoof-and-mouth disease in 1924. Two purposes could be accomplished by transferring deer from Yosemite Valley in the Merced watershed to the Tuolumne drainage, and this has been done for several seasons, the method being to entice the animals into a corral, then load them on trucks for immediate release at the destination. The transplanted animals have not tended to drift hack, so that the deer population of the valley is now more nearly within bounds.

Because a return of the mountain lion to the area is unlikely, due to the fact that all lions ranging in the park can be, and are, taken outside the boundaries, transplanting of deer may have to be more than a temporary measure of relief. However, throughout the park system the Service's policy of strict protection for predatory species is doing much to avert similar problems.

PROBLEMS OF GEOGRAPHICAL ORIGIN

FAILURE OF PARKS AS INDEPENDENT BIOLOGICAL UNITS

The preponderance of unfavorable wild-life conditions confronting superintendents is traceable to the insufficiency of park areas as self contained biological units. In the present era of park development, this geographical cause ranks as the most important of the three major causes of wild-life problems. If the influx of visitors were to increase in the future at the same rate that it has in the past 15 years, competition between man and animal in the park could easily become more influential in faunal maladjustments than the geographical factor.

At present, not one park is large enough to provide year-round sanctuary for adequate populations of all resident species. Not one is so fortunate – and probably none can ever be unless it is an island – as to have boundaries that are a guarantee against the invasion of external influences. To all this the practical-minded will immediately retort that an area with artificial boundaries can never be a true biological entity, and obviously this is correct. But it is equally true that many parks' faunas could become self-sustaining and independent if areas and boundaries were fixed with careful consideration of their needs. Already many parks are being improved in this regard, and there is a vast amount more that can be done.

When all advisable enlargements and boundary corrections have been made, there will still be external influences and probably some range in adequacies to be reckoned with and some management measures will be necessary for the protection of the affected species. Whereas both general types of problems due to the inadequacies of parks as independent biological units must be met primarily by changing the boundaries, as the only means of dealing with the fundamental cause, success can not be as great in one instance as the other. By his action, man can restore a needed range to a park provided he is willing to do it, but there is absolutely no way he can keep every unfavorable influence out of that park – not so long as boundaries are artificial, and some of them must always be that.

CONDITIONS CAUSED BY FAILURE TO INCLUDE THE COMPLETE ANIMAL HABITAT

Unfortunately, most of our national parks are mountain-top parks. During the summer, game retreats to the higher elevations. With the coming of winter the game drifts down below the park, away from protection. For a wild-life preserve this is obviously an unsatisfactory condition. It is utterly impossible to protect animals in an area so small that they are within it only a portion of the year. It is just as fundamental to protect the whole range of the resident fauna of any park as it is to protect the watershed of any stream for its water supply. One would not think of just protecting a narrow zone across which the water flows, but would extend the protection to the natural boundaries of the watershed. In like manner, it is useless to draw up imaginary and arbitrary boundaries for a park and expect to protect the animal life drifting through. This is exactly what has been done in creating the national parks – a little square has been chalked across the drift of the game, and the game doesn't stay within the square. In order that our parks may be able to adequately protect and preserve their wild life as part of our national heritage, it is essential that they be formed principally of natural boundaries, and not arbitrary boundaries. Natural boundaries in this case mean natural barriers limiting the range of the wild life concerned. While the natural boundaries are not definite lines, they are sufficiently tangible in character to be capable of practical establishment. It is now, perhaps, too late to establish natural boundaries completely around all parks, but that is no reason why they should not be established where it is still possible.

If natural boundaries are natural barriers limiting the range of the wild life of any particular area, more definite designation of what these natural barriers should be is necessary. The natural barriers are different for each park, and must be treated as individual problems in each case. But if there is any value in a generalization, this much might be said: As a natural barrier, a mountain crest is better than a valley or stream, but the lowest zone inhabited by the majority of the park fauna is probably the best of all.

All of the western parks are mountain areas. Some of them are a fringe around a mountain peak; some of them are a patch on one slope of a mountain extending to its crest; and some of them are but portions of one slope. All of them have arbitrary boundaries laid out to protect some scenic feature. But our national heritage is richer than just scenic features; the realization is coming that perhaps our greatest national heritage is nature itself, with all its complexity and its abundance of life, which, when combined with great scenic beauty as it is in the national parks, becomes of unlimited value. This is what we would attain in the national parks. In order to attain it, their boundaries must be drafted to meet the needs of their wild life. The entire complexity of wild life can be protected only within natural barriers. In establishing the boundaries, natural barriers should be followed.

Because so many of the national parks are in the high mountains, the seasonal habitat usually lacking is winter range. One exception where the reverse is true is Grand Canyon; but as it is such an uncommon case, it is discussed under that park only. Lack of summer habitat is not one of the major types of wild-life problems.

ANIMALS CUT OFF FROM WINTER RANGE (5)

Situations where park animals are suffering from lack of winter range must be met by extending the area to include the needed habitat if there is any possible way of doing so. There is an alternative in management, but it is a poor expedient at best, having several unfortunate consequences of its own. Artificial feeding is expensive. Concentration at feeding stations is a potential for the spread of disease. There are unguessed possibilities for harm in wild animals. Besides, holding game herds in the higher altitudes of deep snows exposes them unduly to carnivores. This means that additional management to protect them against the unnatural and excessive exposure to their enemies is required; and it is always undesirable to create a condition which necessitates interference with the predatory species in a park. The so-called northern elk herd in Yellowstone is an example containing all the elements of this type of problem, but it has been ably covered elsewhere by William Rush 10 in his 3-year study of this herd. Consequently, another example has been chosen for treatment here.

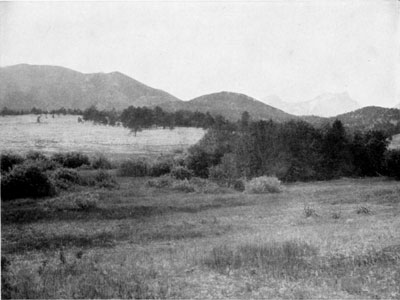

FIGURE 16. – One of the meadows in Beaver Park frequented by the park elk and a necessity to them in winter. Photograph taken June 26, 1931, in Rocky Mountain. Wild Life Survey No. 1895 |

Elk range in Rocky Mountain. – American wapiti were so abundant in this section in early days that market hunters took them out in wagonloads. They were almost exterminated and were later reintroduced from Yellowstone. There are now believed to be approximately 350 in the area, and Rocky Mountain National Park is already faced with an elk problem.

Elk on the east slope require the grasses at the edge of timber and above for summer range, the forested middle slopes for protection and calving, and the open valleys lower down for winter range.

The present park has suitable area for the first two requirements, but none for the third, which is, of course a critical one.

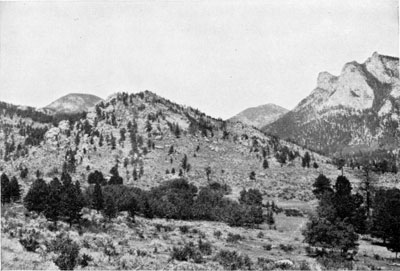

FIGURE 17. – The mouth of Black Canyon supports stands of antelope brush (Purshia tridentata), aspen, and other browse vital to elk and deer in winter. Photograph taken June 26, 1931, in Rocky Mountain. Wild Life Survey No. 2425 |

The eastern boundary is intersected by a series of open mountain valleys which are privately owned and therefore lie outside of the park proper. These valleys, including Estes Park itself, are the natural and only available winter range for the elk. They drift down into these parks in winter, destroying fences, gardens, hay stacks, etc. Consequently, they are very much disliked locally. In harboring the animals the Park Service accepts a responsibility that they should not be a nuisance to the countryside. If the problem is not met squarely, and, as a result, the elk are looked upon as a liability instead of an asset, both the elk and the cause of conservation will suffer.

The crest of the foothills just east of Estes Park would be the most nearly ideal natural boundary for the park; but for a long time to come the best that can be hoped for by way of a solution is to purchase the private holdings in the small higher valleys, namely, Moraine, Beaver, and Horseshoe Parks and Black Canyon. The program of enlarging this section of the park is being carried on at the present time. This is the first and most important step in the solution of the problem, but it is by no means the last. The meadows in these parks have been heavily grazed by domestic stock, mostly horses, for years. As the lands are acquired, a range-management plan is being formulated for the restoration of the range to its former high carrying capacity.11

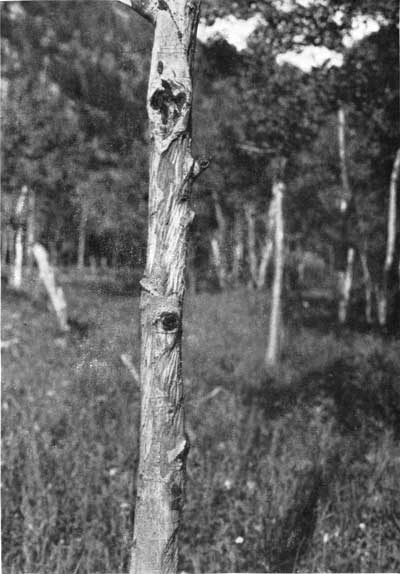

During the winter of 1930 aspen was extensively barked by the elk. This was the first indication that the elk herd was reaching the limit of its food supply and that range abuse and starvation were in the offing. If this is happening when there are only 350 elk in the park, it is indication that even with the addition of the valleys above mentioned there will be a definite limit to the population of this species that Rocky Mountain National Park will be able to support without endangering both park and elk. The situation will have to be carefully watched, and increase beyond the allowable maximum checked if natural balances are not effective.

To sum up, this problem is caused by failure of the park to include all the seasonal habitats of the elk. The basic cause will be largely corrected by extension of boundaries to include winter range. This will have to be followed, as a second step, by a temporary range-management plan to restore the vegetative cover on the added lands to their vigorous primitive condition. Beyond that, a third step in the form of artificial control may be necessary if the elk continue to increase without reaching a natural balance. Within an area as small as Rocky Mountain Park it is unlikely that a natural balance ean be established, hence the excess above a safety point will have to be disposed of in some way.

FIGURE 18. – Aspen barked extensively by elk for the first time indicate that shortage of winter forage is beginning to be felt. Photograph taken June 24, 191, at Fall River Lodge, Rocky Mountain. Wild Life Survey No. 1928 |

10 Final Report on Elk Study, Northern Yellowstone Herd, by Rush, W. M. Yellowstone Park, Wyo., 1932.

11 Report on Conditions of Portions of Elk and Deer Winier Range in Rocky Mountain National Park, by McLaughlin, John L. Rocky Mountain National Park, Colo., Jan. 15, 1932.

CONDITIONS CAUSED BY EXTERNAL INFLUENCES

The extent to which the fauna of any particular park suffers from adverse external influences depends upon three factors, namely:

(a) How much the fauna in the surrounding territory has been altered from its primitive condition.

(b) How adequate the area of the park is.

(c) How nearly the park boundaries follow natural barriers.

Every park is surrounded by territory in which the wild life has been greatly changed, but in some cases the aridity of the faunal life in such regions has become so great that the vitality of the park fauna is sapped at every boundary. Inasmuch as the external factor itself can not be generally controlled, resort must be had to improving the other two conditions. Increasing the size of the area and bounding it by natural barriers will help in many cases, but some encroachments, such as the spread of certain exotic plants or animals into a park, can not be stopped by any of these methods. Management measures to counteract these influences may be worked out in some instances, but there will be others where nothing that can be done is likely to correct matters.

FIGURE 19. – River otter is one of the fur-bearers that can only be perpetuated in parks of large area. There are few places where the otter trusts man enough to play in the waters of a small lake while people watch from shore. Photograph taken July 10, 1931, at Bear Paw Lake, Grand Teton, by B. H. Thompson. Wild Life Survey No. 2424 |

CARNIVORES DRAINED FROM PARK BECAUSE BLACKLISTED OUTSIDE (6)

As regards their faunas, the parks stand in a peculiar relationship to the surrounding regions. Local residents in one breath praise the park as a breeding refuge for game to stock the countryside and in the next condemn it as a nest for the predatory species which they call vermin. The park standpoint is quite different. It has a special duty to protect the carnivorous forms which are blacklisted everywhere else. Game species do receive some consideration elsewhere, but the carnivores are insistently destroyed.

The draining away of the normal predator population is a more complex problem than just the loss of a member or two of the native fauna. It involves the danger of an abnormal increase in the ungulates which, in turn, involves abuse of the flora, and so on.

Because of their wide ranging habits and scarcity per unit area, it is relatively easy to almost completely deplete the smaller parks of these blacklisted species. Consequently, solution of this type of problem is to be sought in enlarging the size of the park. As the predators are generally less restricted by natural barriers, little can be done for them by merely changing boundaries without greatly extending the protected areas. In the case of mountain lions and wolves, especially the latter, it is doubtful if there is at present any park large enough in which they may be saved. The mountain lion is tenacious and may hang on in this country for a long time, but the wolf is already close to extermination. There is little likelihood that protection would be granted to wolves in areas adjacent to the parks, so they probably will go entirely. The coyote, on the other hand, prospers in spite of man and does not constitute a problem in this regard. Some of the smaller carnivores, including many fur-bearers, such as wild cat, fisher, wolverine, badger, otter, etc., may be saved by enlarging the parks and perhaps by providing some other protective management measures.

Wolverine in the parks of the United States. – As the example selected for problems of this type, the wolverine can be best treated by considering its status in all the parks of the United States in which it was a native. Comprehension of this question depends upon appreciation of the relation the parks bear to the status of the species as a whole.

Among our animals the wolverine is one of the most unique and interesting. On the other hand, it has been one of the most persecuted because of its fur value and also because of its annoying habit of robbing trap lines. This persecution continues in the areas surrounding the parks where wolverines are still found and, owing to their wandering habits, keeps them drained away so that they will soon disappear from these last stands.

According to records of past conditions, the wolverine was never so abundant in the United States as in Canada, being restricted to the higher life zones. It is almost gone from this country now. There are a few wolverines in Sequoia National Park (estimate of nine in superintendent's 1931 report), perhaps more than in any other of our western parks. The wolverine of Sequoia is a different species than the Canadian wolverine. In Yosemite, Grinnell and Storer report the capture of two wolverines at the upper end of Lyell Canyon in July, 1915. At several other places in the park, tracks were seen which they ascribed to wolverine.12 In July 1929, a wolverine track was seen in moist sand near Saddlebag Lake, just outside the boundary, by our party.

There seems to be no indication or record of wolverine in Lassen Volcanic or in Crater Lake National Parks. At Mount Rainier tracks of wolverine are occasionally seen. October 3, 1930, our party saw tracks of wolverine on Burroughs Mountain, by Sunrise Park. In Glacier National Park, Vernon Bailey13 reports a few trapped and killed at various places in the park between the years 1895 and 1910, but doubts whether any are present now, although he stresses the possibility of their wandering in from elsewhere. In the Yellowstone-Teton region, a few wolverines may still be present. They have been trapped outside of the parks, and occasionally tracks are seen. In Rocky Mountain National Park they were present in moderate numbers during the pioneer days of that region, but none has been seen in or near the park for many years, and they are believed to be gone from the region.

The foregoing data give a general picture of the present status of wolverines in those western parks where they should naturally be. It is evident in each park that their numbers have greatly decreased, this decrease being primarily due to trapping, the direct agency of man.

What can be done? There are several things which would help the wolverine to come back.

(a) Consciousness of the problem is the first step. Without being aware of the plight of our fauna, nothing could even be tried.

(b) Since wolverines are great wanderers, it would be well to consider the requirements of their range in establishing or completing boundaries. Enlargement of park areas in the upper Canadian and Hudsonian zones would increase their chances greatly.

(c) As most of the parks concerned could not be made large enough to be ideal in this respect, a protective zone, free from all hunting and trapping, might be established around each park as a further safeguard.

(d) Special attention could be paid to the matter of protection from poaching for this and other species known to be in danger. This does not mean that the parks are not patrolled; it merely means that an added emphasis should be placed on protection in these cases.

(e) If all means of encouragement and protection should fail, then in some instances it might be possible to procure and liberate a few pairs for breeding stock. This would be especially desirable in the Rocky Mountain parks, where the common wolverine (Gulo luscus) could be planted. In the Cascade-Sierran parks, no introduction of stock should be even considered until the ranges of the common and southern (Gulo luteus) forms are more definitely worked out. If an intergradation of these two forms should occur in this region, it would be especially valuable, scientifically and educationally, to do nothing that would disturb this natural blending of species. If the wolverines in this area should continue to decrease, then it might be justifiable and necessary to choose breeding stock from the nearest range of the native species for reintroduction into the parks concerned. The feasibility of trapping and transporting wolverines has been demonstrated in the securing of a number of these animals from Alaska for the zoological gardens at St. Louis, Mo.

12 Animal Life in the Yosemite, by Grinnell, Joseph, and Storer, Tracy I. University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif., 1924, pp. 85-86.

13 Wild Animals of Glacier National Park, by Bailey, Vernon, and Bailey, Florence Merriam. National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, 1917, pp. 90-91.

ENCROACHMENT OF EXOTIC SPECIES UPON THE NATIVE PARK FAUNA (7)

This is a situation which is not apparent in many parks at present, but which is apt to become more and more difficult. There are three ways in which man has brought about the introduction of exotics.

(a) Many imported species of animals, notably game birds and fishes, are liberated all over the country each year in the interests of sportsmen.

(b) Exotic species are constantly being liberated by accident.

(c) Certain animals native to one part of the country actually flourish with civilization and invade new ranges in the wake of man. These are exotic in their newly occupied ranges, too.

If any animal introduced by any of the above means takes hold and spreads into a park, serious complications are bound to ensue, for such an animal would not increase if it were not able to displace another form or compete successfully in the utilization of a valuable food supply. Aside from the direct competitive effect, such introductions may have indirect influences, such as disease introduction and production of crossbreeds, but these are treated separately below.

Fortunately, most of the foreign game introductions have not been notably successful. However, captive animals which are liberated, perhaps accidentally, and do take hold are a real danger. Their vigorous adaptive qualities are a menace to native wild life. The opossum, which has recently arrived in Sequoia National Park, is an example. The same is true of the animals which thrive and spread where man goes. They are exceptionally adaptive and aggressive, or they would not have been able to go with him. Certain ground squirrels and the coyote are notable examples.

Effective ways of dealing with this type of problem remain to be discovered. The size of a park is of no avail and such species do not recognize many natural barriers. It is to be hoped that some practical means of preventing encroachments will be found before it is too late.

Coyote in Mount McKinley. – The spread of the coyote is a difficult and insidious problem. The reasons for its sudden spread over vast new territories are too controversial to be discussed here, but this outward movement is certainly associated with the changes which human populations have wrought. In Mount McKinley National Park its invasion is looked upon with great alarm.

Regarding the spread of the coyote, E. A. Goldman14 says:

"Formerly they occupied the western plains and basal mountain slopes from western Canada and the United States south over the tableland of Mexico, and the tropical savannas along the Pacific coast as far as Costa Rica . . .

"In recent years coyotes have pushed northward, however, from British Columbia and Yukon Territory into the Yukon Valley and are reported to have reached Point Barrow, Alaska, and the mouth of the Mackenzie River in Canada . . .

"According to a resident of Telegraph Creek near the Stikine River, Canada, no coyotes were known in that section prior to 1899 . . .

"The movement into new territory evidently began in early days. Vernon Bailey states that coyotes were absent from parts of southeastern Minnesota prior to 1875 when they first appeared in Sherburne County, presumably from the great prairies west of the Mississippi River. When they became common, the red foxes, formerly numerous, practically disappeared . . .

"Coyotes entered the upper peninsula of Michigan about 1906, and have even gone into forested sections near the coast in Oregon . . .

"They are also being reported from localities east of their former habitat on the western plains. . . . Small colonies are reported in western, central and southeastern Alabama."

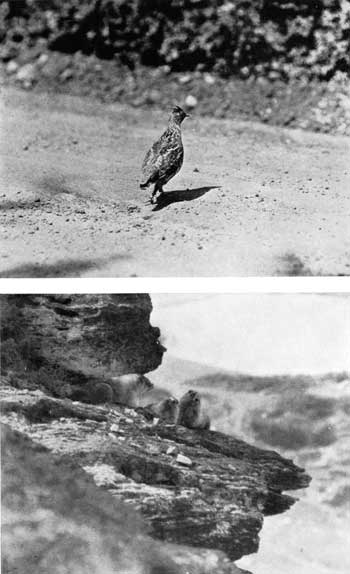

In his field notes, Dixon reports the skull of a coyote which was killed at Mount McKinley Park in 1926. Since that time the coyote has been gradually encroaching on the park. Similar experiences elsewhere indicate that it will tend to displace the abundant Alaska red fox, and perhaps the wolf, too, in the only national park where that animal still figures. The effect of a new and formidable enemy upon ptarmigan, curlew, mountain-sheep lambs, caribou calves, etc., can only be conjectured.

Mr. Stokley Ligon's analysis of the problem, which applies here very well, is essentially this: The coyote is beneficial in its own range and habitat; but when it gets outside of its own range, as it has done many times, it becomes a different animal and is destructive.

First of all, it is the aim of the National Park Service to maintain primitive conditions in the national parks. If this is to be accomplished, the coyote, where it is native to the park (it is clearly not native to Mount McKinley), has as much right as any other member of the park fauna. It is to be considered just as worthy and desirable as elk, moose, or deer. Indeed, when it is seen, it is a great attraction. There is sometimes a tendency in men in the field to hold any predator in the same disreputable position as any human criminal. It seems well to comment that no moral status should be attached to any animal. It is just as natural (just as much a part of nature) for coyotes to prey upon other animal life as it is for trees to grow from the soil, and nobody questions the morality of the latter. This is one angle of the situation.

The other side is that in relatively small areas, such as Mount McKinley and Yellowstone, where the wild life is of greatest importance, it is impossible to preserve that wild life and allow the encroachment of exotic predatory species or of abnormal numbers of the native ones from the outside. The antelope and mountain sheep of Yellowstone could be easily exterminated and the loss would be great, whereas the coyote is of such wide distribution that its extermination in Yellowstone is not probable. Even if it were exterminated in that particular area, it would soon reinvade. Actually it is remarkably abundant, though some control work is carried on.

The logical course of action seems to be this: If coyotes are present in a park in greater numbers than formerly but give no indications of unusual damage, they should not be molested. We do not know enough about the causes of their increase yet to justify steps against it. In Mount McKinley, where the animal life is of great importance and where the coyote does not belong, every safe step should be taken against its encroachment as an exotic and an alien. In Yellowstone, where certain species such as antelope, mountain sheep, trumpeter swan, and sandhill crane need special protection, the coyote must be controlled. Mount McKinley and Yellowstone are at present the only parks where circumstances clearly justify coyote control.

Inasmuch as there is no way of preventing the invasion of the park at the boundary line, the word control is used advisedly. It is the only way to meet the coyote problem. The solution could be a satisfactory one if there were any practical selective method which could be used. Shooting is selective, but it is costly and not sufficiently effective for the coyote. Trapping is the next best. It is effective but not selective. In Mount McKinley the prized foxes and wolves, as well as wolverines and others, would suffer, too. Poisoning, of course, could not be allowed. It would be better to have the coyote. When a satisfactory method for taking coyotes without harming anything else is discovered, one of the most puzzling of all wild-life problems will be solved.

14 The Coyote–Archpredator by Goldman, E. A., Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. XI, no. 3, August, 1930, pp. 327-329.

DILUTION OF NATIVE STOCKS BY HYBRIDIZING (8)

The distribution of vertebrate life and correlation of speciation with geographic range is one of the most fascinating of zoological studies. The ranges of some forms were not even worked out before those animals were exterminated. This is true of the grizzlies. So many of the grizzlies are extinct that the taxonomy of the species will never be fully known.

But this is only part of the story. There is a great and growing tendency to transplant animals from one part of the country to the other without any regard to the native range of each form. This means hybridization of one subspecies with another and a gradual muddling until many forms are lost.

In the national parks it is especially desirable to preserve the pure native strains. This can not be done if related subspecies of the park animals are introduced in adjacent territories, and consequently the only solution for problems of this type is to seek for a reform in restocking practices. The only way to secure protection would be to designate a Federal commission or agency through which all stocks for transplanting purposes would have to be cleared.

Elk transplants from Yellowstone. – This needed reform in restocking practice might well start with the National Park Service itself. The elk of Yellowstone (Cervus canadensis canadensis) have been planted widely within the range of the other species and subspecies of this animal. There are Yellowstone elk in Rocky Mountain, Mount Rainier, Crater Lake, and the Guadalupe Mountains by Carlsbad. At the time the Yellowstone elk came to Rocky Mountain there were probably still native elk in the park. While it is true that they were supposedly of the same species, nevertheless any possibility of studying intergradations or races which might have existed is now lost. The Yellowstone elk in Mount Rainier have drifted in from the Cascades east of the park.15 Probably the original elk of Mount Rainier were the Roosevelt elk, and therefore any reintroduction should have been of this species. If there were ever elk in the Guadalupe Mountains, they were probably the Merriam elk, a southwestern species now extinct. In any event, there would be little value in having Yellowstone elk down in the Guadalupes. There are many who believe that the educational value of seeing an animal lies in the significance of that animal's relation to its environment and past history. When the species are mixed or replaced, there is nothing left but just another elk.

The purpose of this discussion is to bring up the question of Park Service policy on shipping breeding stock to alien localities. It so happens that none of the elk plants discussed above was made in the parks where the elk now exist. But they were distributed in response to outside requests. Because of their proximity, they drifted into the parks, and the results were the same.

The situation seems to indicate that the Park Service, in order to protect its different faunas, would be justified in establishing the policy of shipping animals only to points within their native range (museums and zoological gardens, of course, excepted).

Caribou and reindeer in Mount McKinley. – This is a striking illustration of the danger that an outstanding native park animal may be lost through hybridization with an exotic variety introduced in the surrounding region.

Ten reindeer from eastern Siberia were introduced into Alaska in 1891. By 1902, 1,280 reindeer had been imported. To-day these animals number about 200,000 in Alaska. Being very closely related to the caribou, they hybridize readily; so that the future status of the caribou is questionable. The reindeer industry has spread eastward across Alaska until reindeer are now at Broad Pass, just outside of Mount McKinley National Park. The caribou of Mount McKinley are one of its great values. While the Mount McKinley caribou are separate from the main caribou migration in the north and east, they are nevertheless a considerable band, of about 50,000, with a local seasonal migration, and they are so situated as to be on the reindeer frontier unless some measure is taken to keep reindeer away from the Mount McKinley area. In 1926 Dixon and Wright saw reindeer, caribou, and hybrids in the park. Now, with the stated aim of the industry to hybridize caribou and reindeer and the natural tendency for this hybridization to occur anyway, it becomes increasingly valuable to maintain the Mount McKinley caribou as a pure strain. The Park Service, the Biological Survey, and many others recognize this situation and are trying to prevent its unfortunate consequences. Whether anything can be done to save the Mount McKinley caribou, ultimately, is a question.

Aside from hybridization or driving out native forms, the great danger in all such introduction of exotics lies in the possibility of bringing in some pest on disease which would prove fatal to the native species. No reindeer plagues have occurred in Alaska yet, but we do not know the potentialities.

15 Mammals and Birds of Mount Rainier National Park, by Taylor, Walter P., and Shaw, William T. National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 1927, p. 116.

EXPOSURE OF NATIVE SPECIES TO DISEASES AND INFLUENCES OF ALIEN FAUNAS (9)

One of the fundamental principles governing the distribution of animal life is that when the faunas of two different continents meet, the fauna of the larger continent will be the survivor. There is abundant paleontological as well as present-day evidence substantiating this fact. When we bring domestic stock, particularly sheep and cattle, in contact with native game, we are exposing the native game to members of the Asiatic fauna. This brings in new diseases and new conditions with which the native fauna has not had to cope before, and the results are apt to be disastrous.

All livestock and wild game are subject to many different diseases and parasites. If an outbreak occurs in domestic stock, there are chances of its being controlled. If it gets into the native wild life, it is apt to run its course, with irreparable damage. There is one important exception to the foregoing statement, and that is the control of the hoof-and-mouth epidemic among deer in California, 1924. The plague was stamped out by killing 22,214 deer. But it is obvious that any such remedy would be fatal to mountain sheep, mountain goats, antelope, elk, moose, or any other rare forms of animal life.

It is not actually necessary for domestic stock and native game to come in contact for the damage to be done. Even use of the same range may be just as effective, for some of the most viable disease germs may be carried in the soil for years to start a new outbreak.

Because of the above circumstances, it is clear that the only way to treat problems of this type is to prevent possibility of their occurrence. This can be accomplished for species occupying a restricted range by keeping domestic stock out of a neutral zone between the two. This would work with mountain sheep or antelope, but not so well for deer or elk. Fortunately, the rarer species are the ones to which it is most feasible to extend this sort of protection.

Where a disease has already been contracted by a park animal there is but little that management can do so far as is known at the present time. The first step is to adjust the park boundaries so as to prevent reinfection through the same avenue. The spread of disease may sometimes be checked by destroying carcasses of infected animals. In another case the disease might be eliminated by destroying the alternate host where that host was not a rare form and could be counted upon to reinvade the territory later on when the disease had been conquered.

Sheep scab in Rocky Mountain. – There is some dispute concerning whether the wild sheep of America were subject to sheep scab before the introduction of domestic sheep, but the evidence seems to point to the fact that they were not. Numerous accounts tell of heavy losses of mountain sheep from sheep scab in the pioneer days of the sheep industry in the West. Merritt Cary16 says: "A danger which threatens mountain sheep in Colorado, as well as in other Western States, is the introduction of scab from domestic sheep allowed to graze on the higher mountain slopes." Warren17 says: "C. F. Frey tells me they suffer much from scab in the West Elk Mountains, and that a party told him in 1902, at one place near the head of Sapinero Creek, 75 head were counted which had died of scab. Domestic sheep had been run in that locality, and the wild sheep doubtless contracted it from them."

Aside from the question of origin of the disease, the fact remains that whereas domestic sheep may be treated and cured of sheep scab, there is no known way of dealing with it in mountain sheep. When the survey party was in Rocky Mountain in 1930 and in 1931 the mountain sheep were scabby. Reports of local residents indicated that scab had been present for many years, being worse in some periods than others. Domestic sheep had been run in these mountains for so long that it was not possible to determine definitely that the wild sheep were not subject to an endemic form of sheep scab.

The sheep situation in Rocky Mountain should be investigated thoroughly. In the meantime reinfection should be prevented by removing the domestic sheep as far as possible from the mountain-sheep range. The Never Summer Mountains addition has already been an improvement in this regard.

16 A Biological Survey of Colorado, by Cary, Merritt. North American Fauna No. 33, 1911, p. 62.

17 The Mammals of Colorado, by Warren, Edward R., 1910, p. 238.

PROBLEMS OF COMPETITIVE ORIGIN

CONFLICT BETWEEN MAN AND ANIMAL IN THE PARKS

Since he is in the parks permanently both as resident and seasonal visitor, man must henceforth be considered an integral part of those microcosms. The significant difference between himself and all other ecological factors is that he is conscious of his relationship to the other elements of the park world and hence can regulate, or at least modify, his influence to suit his own purpose. It happens that in the parks the purpose dominating man's relations to his environment is the maintenance of all the animal and plant life in an unmodified wilderness state. In order not to defeat his own ends, he contrives that his presence shall disturb the wild life to the very smallest degree that his ingenuity can manage.

This means that painstaking consideration for the welfare of the fauna must accompany the development of every phase of human occupation of the parks. Yet developments in the era just closed have not always been characterized by as much restraint as a delicate situation required. This was only natural in a time when the principal preoccupations were making the parks accessible, attracting the visitors to them, and making them comfortably at home while there. But in the era opening ahead, the critical faunal maladjustments that have already been created, as well as those just raising their heads, must be dealt with in a farsighted manner. For if the wild life continues to give back before the growing pressure, man will presently find that he has unwittingly destroyed the very thing which he came to the national parks above all other places to enjoy.

In considering the effects of man's intrusion in the total environment which is the park, it is apparent at once that certain faunal complications are inevitable, if for no other reason than the quantitative displacements which must take place. These problems are rooted in the conflict of the more fundamental needs of man and animals in the parks. As their cause is man's presence and that presence is not only continuing but constantly increasing, they must be treated accordingly. These problems are essential by-products of the sharing of a common habitat by man and animal.

There are other complications, however, which are not caused so much by man's actual needs as by his ideas of what wild animals are and how he should see them. Inasmuch as these are problems caused by human concepts which can be changed, they are subject to control at their sources. It is necessary to analyze these problems to fully realize that they arise from man's efforts to force the animal life to actually fit his concept instead of developing his concept to fit the wild life as it really exists in its natural setting.

These difficulties are more truthfully problems of human nature than of animal nature. In dealing with them it becomes necessary to enter the fields of philosophy and psychology, because, after all, the national parks are an experiment in these fields. Wherever he goes, man unconsciously tries to surround himself with the things to which he is accustomed. He abhors change. Consequently almost any labor in transplanting whole environments is found preferable to the effort of reconditioning to new circumstances and concepts. Coming from the city, man tries to approximate in the park the conditions he left behind. If his eye is met by a planting of his home flowers arranged in garden pattern, he praises it as a beautiful improvement unless his viewpoint has been reeducated to an appreciation of the park's own distinctive wild gardens, and then it becomes a jarring note on the landscape.