|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 1 A Preliminary Survey of Fauna Relations in National Parks |

|

CONSPECTUS OF WILD-LIFE PROBLEMS OF EACH PARK

As desirable as it would have been to make the preliminary study inclusive, circumstances did not permit visits to every one of the national parks. Therefore there are a few which do not appear in this section. Most emphatically this does not mean that they are not significant as regards wild life nor that they have no faunal problems. Some of the parks which were said to have no important vertebrate animals were found, on the contrary, to have unusual interest from this standpoint. Nearly every park can add some forms to the quota which will some day give the national parks a full representation of all the fauna of our country. The assumption should be that every park and monument shall be carefully studied for the animal life that it either has or, by restoration, should have.

Lest the wrong significance be accredited to the treatment of faunal problems by parks in this section, the reassertion is made that the survey did in no case make a complete study of the thoroughgoing sort outlined in the chapter on Methods Adapted to Faunal Investigations. Where only weeks were available in any one place for the preliminary survey, it will take months and years to make the exhaustive studies. However, it was possible to get a general picture of the status of wild life in each of the parks visited. Some of the basic conditions causing faunal maladjustments in each park were noted and some suggestions on how to attack the problems were formulated. These observations are recorded here not to take the place of further work but to stimulate it and perhaps to serve as a prospectus.

It is because there is a useful significance to the arrangement, from a biotic standpoint, that the parks have been grouped here by regions. The Southwest parks are alike to the extent that analysis of faunal relationships in one of them will be helpful to a study of others in the group. Eastern parks show a greater disparity, yet even here there are similarities of topography and climate which give them a unit character and the grouping has administrative value.

SOUTHWEST PARKS

Bryce Canyon, Carlsbad Caverns, Grand Canyon, Mesa Verde, and Zion are the national parks of the desert. They are characterized by plants and animals which are highly specialized to cope with the rigors of arid climate. Their special adaptations and their triumph in a portion of the world that, to us at least seems hostile to life are constant sources of interest to the traveler.

On the other side, the relations between fauna and environment are so critical that even slight disturbances may be disastrous. For instance, the mammals and birds of many square miles are sometimes dependent on a single water hole. If this is destroyed or preempted for human use, the wild life of that particular area will suffer accordingly. Bunch grasses are easily destroyed by grazing, and the forces of erosion readily loosed so that floods carry away the necessary and all-too-scarce green bottoms and leave the precious springs to go dry the rest of the year.

FIGURE 39. – The Bailey collared lizard is one of the specialized forms of animal life which are found in the desert. Photograph taken May 31, 1931, in Zion Canyon, Zion. Wild Life Survey No. 1842 |

It behooves man, because of these things, to tread lightly in developing these parks. The greatest circumspection must be used in order that the wonderful desert life which is one of their distinctive attractions shall not be destroyed.

BRYCE CANYON

At Bryce Canyon the situation is such that protection of animal life is a virtual impossibility at present. The park is about 3 miles wide by 20 miles long. Sheep and cattle are grazed all around it. And on these grazing lands the predators are trapped, hunted, and poisoned. Even though the park embodies only a narrow strip of cliffs, it is charged by the stockmen in the vicinity that it is the breeding ground of mountain lion, coyote, wild cat, and other predators, and the extermination of these animals in the park is demanded. The lands recently added to the park still carried the signs posted by field men of the Biological Survey, and on the trail leading up to Bryce Natural Bridge could be seen the remains of a mountain lion trapped on the rim in 1930. Under such circumstances it is impossible to have primitive conditions in the park. The question is not the justice or injustice of the stockmen's point of view; it is merely a presentation of the fact that animal life can not be effectively protected at Bryce under the present circumstances.

Overgrazing has long been apparent in the region all around Bryce. Readjustments will come inevitably in the sheep industry in this section because the poverty of the range will check the industry. If the range within the park can be preserved from further destruction, much can still be accomplished toward restoration of animal life in the park. Sheep and cattle must be excluded from the park as soon as possible. Cattle drift into the park along the west-entrance road and along the entire west boundary. Immediately west of the park a long, narrow, grassy valley, through which a branch of the Sevier River flows, parallels the park line. Cattle and horses are grazed in this valley. The park boundary is an artificial line following the section lines zigzag fashion up through the timber just above this valley. Obviously there is nothing to prevent domestic stock from entering the park. An attempt was made to establish a game preserve down to the stream in the center of the valley, but was defeated by local opposition. There seems to be only one other course; that is, to acquire this valley for the park, and move the boundary to the crest just west of this little Sevier Valley. Such a course is the only way to protect both the fauna and the flora of the park.

CARLSBAD CAVERNS

A cursory examination of the interesting animal and insect life of the caverns gave us the impression that on the whole it remains unhampered by the introduction of the human factor. The bats, ring-tailed cats, spotted skunks, cave mice, crickets, spiders, and flies were all about their dark and devious businesses.

The surface area of the park is insignificant, offering small asylum for the wild life of the region. After hours of isolation from the living world, the green plants and moving creatures of sunlight were hungrily sought for. We were entertained by the nesting activities of a pair of cactus wrens close by. A rock wren dined on delicatessen fare, cold-storage insects from the radiator of an old Cadillac bus. A horned toad sat blinking in the center of a white-pebbled ant hill. Curve-billed thrashers, black-throated sparrows, and rock squirrels were seen within a radius of 500 feet of the cave entrance.

FIGURE 40. – A pair of cactus wrens were building this nest near the mouth of Carlsbad Caverns. After the visitor has spent hours in the still dark cave, the bustling activity and lively calls of these wrens and other surface dwellers provide a welcome contrast. Photograph taken April 25, 1931, at Carlsbad Caverns, by G. M. Wright. Wild Life Survey No. 2411 |

The cavern, however, is located at the very edge of a wonderful game country. The valleys and canyons of this region tap the great faunal reservoir of the Lower Sonoran Zone, which spreads away to the south and down into Mexico. Immediately adjacent rise the Guadalupe Mountains, a high desert range intersected by deep, hidden canyons and wild gorges where there is haven for many of the rare animals now gone from the more settled localities. This was the natural habitat of peccaries, mountain sheep, deer, mountain lions, wild cats, wolves, coyotes, grizzlies, black bears, and the colorful birds of the desert, such as the pyrrhuloxias and phainopeplas, and even the rare zone-tailed hawk and Aplomado falcon of the arid tropics. The plants range in type from the sotol, lechuguilla, and narrow-leaved yucca of the desert up through the junipers and straggling hardwoods to the yellow pine forest on top of the mountain.

The Carlsbad region takes on added significance in the enlarged concept of the national parks to include the preservation of representative and outstanding examples of the biotas of the country. Fauna and flora of this section belong principally to old Mexico. Yet in the northern forms which have found a haven on the cooler walls of the north slopes there is seen a striking mingling of austral and boreal types.

In consideration of flora and fauna, it would be a fine thing to supplement the underground feature of Carlsbad with the addition of the eastern watershed of the Guadalupe Mountains southeastward to their culmination in Guadalupe Peak in Texas. The present park is located in the northeastern foothills of this range.

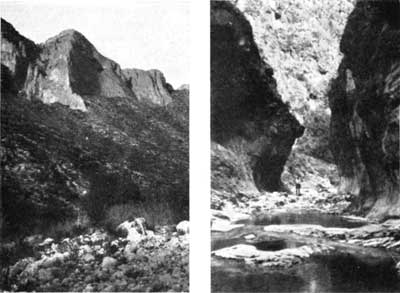

FIGURES 41a, 41b. – Immediately adjacent rise the Guadalupe Mountains, a high desert range intersected with deep, hidden canyons and wild gorges where there is haven for many of the rare animals now gone from the more settle localities. Photographs taken April 25, 1931, in Guadalupe Mountains, New Mexico, by G. M. Wright. Wild Life Survey Nos. 2415 and 2416 |

Four outstanding species native to the Guadalupes have not at the present time a place in the national parks. They are:

MERRIAM TURKEY (Meleagris gallopavo merriami). – This great bird is present in the Guadalupes to-day through reintroduction a few years ago and is reported to be doing well. Mr. J. Stokley Ligon, who assisted in this task, hunted turkeys in these mountains 20 years ago when they were still common.

TEXAS BIGHORN (Ovis canadensis texiana). – The Guadalupe Mountains are the type locality of this rare form. In spite of protection, under the present set-up the Texas sheep is barely holding its own. Estimates indicate that there may be 100 in these mountains. The only other places in the United States where Texas bighorns arc found are the Big Hatchet Range, supporting a few, and the San Andres Mountains, which still harbor a bare remnant.

"It is highly desirable that the main portion of the Guadalupe Mountains, from the Carlsbad Cavern, south to the point of the mountains in Texas, be made a permanent mountain sheep sanctuary and nature wonderland. In order to do this, the area should be set aside as a national park or a wilderness area and left in its natural state, except for saddle-horse and pack-animal trails. This is one of the most interesting, rugged, and picturesque mountain ranges of the country, and is of little use to the State for grazing or other economic purposes; but as a mountain sheep sanctuary and a public reservation, it is of prime importance. There is ample overflow range both in New Mexico and Texas for surplus game and by establishing such a reservation, the citizens of both of these States would be creating a lasting monument of beauty and interest."19

COLLARED PECCARY (Pecari angulatus). – These so-called wild pigs used to roam in the foothill country of the Guadalupe Mountains near Carlsbad Caverns. Years ago they were wiped out of this area by the encroachment of civilization. But they still exist in the desert east of the Pecos River, whence a small supply for reintroduction into the Guadalupes might be procured. This would introduce a very rare and interesting animal to many who would otherwise never see it. It would provide a sanctuary for an animal which is rapidly disappearing. And it would restore to its native habitat an animal which is a unique product of the desert foothills and ravines, to increase the interest and pleasure in this wild and fascinating country.

MEARNS QUAIL (Cyrtonyx montezumae mearnsi). – This bizarre little quail is to be found in the lower places along the Guadalupes where it digs its favorite food, the bulbs of the nut grass. Its numbers are becoming rapidly decimated through the destruction of cover by grazing. In an enlarged Carlsbad Park the Mearns quail would find real protection.

Besides the species noted above which would be of exceptional interest, there are many other forms of wild life, such as kangaroo rats, prairie-dogs, band-tailed pigeons, and scaled quail. The Merriam elk of the Southwest has vanished forever, but the American wapiti has been planted in the southern end of the Guadalupes and is reported to be spreading northward already. The grizzly was exterminated long ago, but the black bear remains.

There is real scenic grandeur in the Guadalupe Mountains and canyons, although the range looks like a barren mesa when viewed from the highway far off in the desert. The Guadalupes are the nearest mountains to a large population south and east of this section of the country, and therefore have a high potential recreational value.

19 Wild Life of New Mexico, by Ligon, J. Stokley. State game commission, department of game and fish, Santa Fe, N. Mex., 1927, p. 92.

GRAND CANYON

Grand Canyon National Park is laid out like most of the Southwest national monuments; that is, a boundary line drawn about the object of interest, the canyon, without regard for faunal requirements. While it is true that the canyon itself is the main attraction of the park, it is also true that nowhere else in the Southwest is there such a varied and interesting intergradation and division of faunal types. Each year the interest in the faunal story of the canyon region is growing. Back of the present status of wild life at the canyon stretches the paleontological story into the distant past. It is this great panorama of the development and adaptation of life as depicted in the canyon which gives it its meaning. We can not think of the canyon as one thing and its meaning as another. They are inseparably and integrally one experience. There is no break between the life of to-day and the primitive life which first left its imprint in the rocks of the canyon. The wild life of to-day is the most vivid part of that story; without it the rest would be colorless and lacking in both significance and reality. It is absolutely essential to the significance of the canyon that its native life be preserved. This means that the park must be made adequate for wild-life requirements.

The greatest danger to the park fauna is along the south boundary. In many places the boundary comes to the very rim of the canyon, so that grazing and lumbering are immediately adjacent to the canyon itself. This rim country is essential as summer range for park animals. To some extent the Grand Canyon situation is the exact reverse of that which obtains in the mountain-top parks of the Northwest: In winter certain animals withdraw into the park; in summer they move out of the park. The territory immediately south of the park has been so severely overgrazed in the past that for miles at a stretch there is almost no forest reproduction, and deer forage has been practically destroyed. This is an arid region which recovers so slowly that it will take many years, even under absolute protection, to recover and again be a suitable faunal habitat. This region should be added to the park to protect its wild life.

The ideal Grand Canyon unit would include the Coconino Plateau and a portion of the grasslands southwest of the present park. That would provide suitable antelope range and include a faunal unit cut off from adverse influences by the desert lying between the Coconino Plateau and the San Francisco Mountains. At present this is impossible of accomplishment, and, therefore, the minimum faunal requirements must be met instead. This would require moving the south boundary back to a line at least 10 miles from the canyon rim at every point. All grazing should then be prohibited in this area to allow it to recover, and deer should not be encouraged.

It would seem inadvisable to extend the north boundary at this time because of the complications on the Kaibab Plateau. Due to the present policy of total protection for all predators in the Kaibab forest and the attempt to restore the range, there is no adverse influence threatening from that side.

FIGURE 42. – Mule deer wintering on this point have browsed the cliff rose (Cowania mexicana) until it presents an excellent example of an abused range, a fringe of the Kaibab Plateau deer problem. Note browse line on cliff rose at far right. Photograph taken June 1, 1930, at Point Sublime on the north rim of the Grand Canyon. Wild Life Survey No. 1128 |

Predatory-animal control has been recently discontinued. There is, therefore, nothing to be said about coyotes, wild cats, and mountain lions until sufficient time has elapsed to form judgment concerning these animals and their effects.

Within the last few years over 1,200 feral burros have been removed from the canyon. Until the vegetation recovers somewhat from the depleted condition which they caused, not much can be said about the animal life of the canyon. Perhaps the mountain sheep will increase as their range improves. They are still scarce.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN MULE DEER (Odocoileus hemionus). – The deer on the north rim of the canyon have been affected by the same causes which resulted in the superabundance of Kaibab deer. While forage conditions within the park are much better than they are on the Kaibab Plateau as a whole, it is evident that there are still too many deer for the range. This statement is made exclusive of the few denuded points along the north rim, which probably are local winter retreats and might be overgrazed any winter if a few deer were forced to remain on such points. But considering a large area such as Powell Plateau, where the "high-water" line shows overgrazing as severely as at any point on the Kaibab, it becomes evident that the range needs special protection until it recovers. Probably the open season each year on the Kaibab Plateau will drain enough deer from the canyon region to relieve this situation.

Deer on the south rim have always been scarce because of lack of forage and water. The south-rim country is essentially a desert country in which the larger forms of wild life are never abundant as they are in more favored regions. It would never be natural to see large herds of game along the south rim. To transplant large numbers of deer or other animals from the Kaibab to the south side of the canyon would be to invite disaster. Even if sufficient water holes were artificially formed, the sparse vegetation would never support many deer, and the south-rim range is already subnormal. Beyond that, it would be destroying all of the significance of the canyon as a natural barrier between related forms of animal life. The significance of wild life on the south rim is that it is in a rigorous niche of nature where only the forms of animal life which could adapt to a desert region are to be found. It is normal in such a region to find few deer, many rodents, coyotes, wildcats, and mountain lions. There would be no point to any move which tended to change this harsh desert life to the sylvan type of forested Kaibab. Every effort should be made to keep these two regions as separate and distinct as they were when white man first found them. Even the bridges at the bottom of the canyon should be guarded in some way to prevent the faunas of the two regions from mingling.

AMERICAN PRONGHORN (Antilocapra americana americana). – The introduction of antelope into the canyon, at Indian Gardens, is still in the experimental stage. Its outcome will be awaited with interest. Whether the antelope will be able to adapt to the confined quarters of the narrow plateau down in the canyon is a question. The antelope is a plains form of animal, dependent upon flight to escape its enemies. This would not be possible in the canyon; hence it would be at the mercy of predators. It would be undesirable if the antelope should successfully increase and spread in the canyon, because where forage is scarce the competition becomes keen even between animals of diverse food habits, such as sheep and antelope. Mountain sheep belong in the canyon and are adapted to it. It would, therefore, be preferable if no alien member were introduced into the canyon, thereby giving the native animal life full benefit of all available range. So long as the antelope of Indian Gardens remain in their present status, they are no menace to other forms of canyon life, but neither do they measure up to the Park Service aim of presenting animal life in its natural habitat.

MERRIAM TURKEY (Meleagris gallopavo merriami). – Wild turkeys were at one time abundant in the San Francisco Mountains region, and are still present in reduced numbers. Whether they ever crossed the intervening desert to the Grand Canyon region is not recorded, to our knowledge. According to Mr. Edward Hamilton, who has lived near the Grand Canyon for more than 40 years, turkeys were never found along the south rim. There is an abundance of food and yellow pine, but a lack of water. If it could be found that they ever existed along the south rim, their reintroduction would add greatly to the interest of the Grand Canyon forest.

MESA VERDE

The logical faunal unit for Mesa Verde National Park would include the whole of the mesa north and west of the Mancos River Canyon. In order to avoid the usual complications of an unprotected winter range, the south and east boundary should not stop with the Mancos River in the bottom of the canyon, but should follow the east and south cliffs of the canyon. Then the entire Mancos Canyon, as winter range, would be within the park. The north and west boundaries of the faunal unit, so outlined, would follow the base of the cliffs where the mesa terminates abruptly on the north and west.

Within this area it would be possible to preserve ail the existing forms of animal life which were of such great importance to the Cliff Dwellers a thousand years ago. This would give reality and color to the desert country as nothing else could.

The present park includes only a portion of the mesa north and west of the Mancos River. Animal life in the region is not now abundant, and it probably pays some toll to the Ute Indians. On the south and west sides of the park there are no present natural boundaries. It is like a house with two sides left open.

Considerable historical research will be necessary before the original (i. e., before white men came) status of animal life on the mesa can be determined. The fauna of the mesa is complex in that it is predominantly Great Basin, but is in close proximity to Rocky Mountain forms.

GRAY WOLF (Canis nubilus). – The gray wolves are probably gone permanently. They were in the mesa region formerly. "According to Mr. Steve Elkins, of Mancos, none have been reported in that region since the winter of 1904-5, when four or five were seen between Cortez and Mancos."20

BLACK BEAR (Euarctos americanus). – Black bears may have been on the mesa in the past, although we know of none now. Merritt Cary reported that "an old female and cub were killed on Middle Mancos River, 10 miles east of Mancos."21

PORCUPINE (Erethizon epixanthum). – See pages 61-63.

BROAD-TAILED BEAVER (Castor canadensis frondator). – Nordenskiöld22 reported beavers in the Mancos Canyon in 1891. Although they would never be abundant in these desert streams, they could still be maintained if sufficiently protected. If Mancos Canyon were included in the park, and the grazing of domestic sheep discontinued, there would be not only more beaver habitats but more forage for all forms of animal life which drift down the canyon in winter.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN MULE DEER (Odocoileus hemionus). – Deer are present, but not abundant, upon the mesa. They are wary and, consequently, not so commonly seen, although their tracks indicate their presence. Water is scarce, but there seems to be evidence that deer can and do go for weeks without it. Forage is abundant. It is thought that deer are taken by the Ute Indians whenever they can get them. However, aside from the question of providing suitable winter range for the deer, no other protective steps are necessary at present.

In 1927 four mule deer were shipped from Yosemite Valley to Mesa Verde. One of them died soon after shipment. Superintendent Finnan reports that the other three have had no fawns. The Yosemite deer are different from the Mesa Verde deer. It is to be hoped that no mixing of the forms will occur from this transplant.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN BIGHORN (Ovis canadensis canadensis). – Mountain sheep may have been on the mesa at sometime in the past. The question of reintroduction of sheep is quite analogous to the wild-turkey question discussed in relation to Mesa Verde on pages 26-27. If mountain sheep could exist on the mesa, they would be a most attractive feature of the park. This question, however, is raised for what it is worth. Since it is the tendency of mountain sheep to bed down in the shade of cliffs and to climb all over the cliffs, how much would this accelerate the destruction of unrestored cliff ruins?

GAME BIRDS. – Wild turkeys have been discussed on pages 26-27. Dusky grouse (Dendragopus obscurus obscurus) are present and seem to be holding their own. Scaled quail (Callipepla squamata) is the native quail of the region. Gambel quail, California quail, bobwhite, and pheasants have all been introduced into the regions surrounding the park. It is hoped that the scaled quail will maintain its range on the arid mesa, and that the exotics will not become established.

In general, the faunal picture at Mesa Verde is a favorable one. Just how much the vegetation and, consequently, animal life have been modified by the early years of cattle grazing and the adverse influences from outside the park is yet to be determined. With exception of the porcupine situation, there are no problems of conflict between animal life and human occupation. The chief difficulty at present lies in inadequate boundaries.

20 A Biological Survey of Colorado, by Cary, Merritt. North American Fauna No. 33, 1911, p. 196.

21 Ibid.

22 The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, by Nordenskiöld, G., 1893, p. 5.

ZION CANYON

The topography of Zion National Park is such that the animal life enjoys a natural protection. The chief difficulties are in the surrounding region. About 60,000 head of domestic sheep are grazed above the park on the Virgin River watershed. This region has been grazed for more than 50 years. The forage is greatly injured, and the erosion severely accelerated. The effect of this grazing upon Zion National Park is evidenced in the enlarged and changing stream bed in Zion Canyon. Old farms which used to lie along the river have been washed away, and the floor of the valley has been cut away to a depth of 15 to 20 feet in many places. If the floor of Zion Canyon is destroyed – it is apt to be if the present tendency is not corrected – the park will be ruined, to say nothing of the damage already done to the winter range.

The greatest danger to wild life, however, is the destruction of the water supply. In overgrazed places the water rushes off the denuded mountain slopes with no time for percolation into the soil; then the water holes are dry when water is most needed. It is also destructive of fish and all other forms of life in the streams. Every effort should be made, in cooperation with the Forest Service, to limit and regulate this grazing above the park. In its present tendency the industry is suicidal, and the damage to the park and range will be irreparable.

Grazing of domestic sheep is carried on dangerously close to the east rim of the canyon, and there is some poaching upon the summer range in that portion of the park. It would be very desirable if the east boundary could be moved a few miles further east in order to give a more effective protection to the wild life of that region.

Within the park a resident of Cedar City owns 540 acres near the Temple of Sinawava. This tract of private land is so vital to the heart of the park that the owner has been given the privilege of grazing an equal portion of land in the northwest corner of the park, in the region of Potato Valley, in lieu of his grazing privileges on the Sinawava holding. The northwest corner of the park is badly overgrazed by sheep, and erosion is severe. Sheep carcasses have been strychnined and left in this portion of the park to poison predators, chiefly mountain lions. It is evident that such a situation is inimical to the wild life of the park. The private holding within the park should be acquired as soon as possible.

BROAD-TAILED BEAVER (Castor canadensis frondator). – Beavers were in the park when the region was first settled by the pioneers. but no beavers have been there in recent years. It has been suggested that they be reintroduced into Zion Canyon, along one of the west tributaries of the canyon, where they could have some seclusion and still be seen from the trails. The reintroduction of beaver, however, seems inadvisable because of the freshet character of the streams due to overgrazing on the watershed, and because the narrow valley floor is now largely occupied by human developments.

MOUNTAIN LION (Felis oregonensis). – Mountain lions are controlled in the region around the park, and the park is scarcely large enough to protect them. The sheepmen in the region consider that the mountain lions in the sheep territory above the park, on the headwaters of the Rio Virgin, are park lions driven out of the park by highway blasting. A sheep herder of a lessee in the park said that on May 24, 1931, a lion killed six sheep two miles east of Potato Valley. Last fall the same sheep herder found two fawns killed in the same region, supposedly by lion. The herder poisoned the carcasses and left them. Ranger Russell reported that a mountain lion and two kittens had been killed in the northeast section of the park about March 1, 1931. Above the park, between Cedar Mountain and Zion, the sheepmen each fall distribute poisoned horse carcasses, but report that they do not get many lions in this way.

The very few mountain-lion depredations about which we could get information do not seem to warrant further control within the park.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN MULE DEER (Odocoileus hemionus). – Deer are plentiful within the park. We saw deer tracks in every section of the region traversed. There is a hint of possible complication for the future if the number of mule deer frequenting the canyon increases materially. Fifteen years ago Yosemite Valley had no more deer than Zion has at the present time. To-day the deer constitute an important problem, having done considerable damage to the flora of Yosemite Valley. Apparently the vegetation in Zion Canyon has not suffered as yet. By careful management such a situation may be definitely averted.

A few deer are killed each fall just below the south entrance to the park. Coyotes are few, and constant warfare is waged against mountain lions in the region. Consequently, the deer are increasing and can afford the losses around Springdale and Rockville, just south of the park, even though this is the natural winter range for park deer. Should the effect of hunting become too serious in this area, protective steps might need to be taken. No such measure seems necessary at present.23

ROCKY MOUNTAIN BIGHORN (Ovis canadensis canadensis). – Mountain sheep are present in the park. They have been seen in bands numbering up to 18 along the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway, and are to be found in the valley behind Bridge Mountain. They are in protected country and seem to be maintaining themselves. However, there are some indications of poaching.

In general, range conditions at Zion have greatly improved since 1900. The outlook is favorable for most forms of wild life. Certain features, as outlined above, need adjustment, but any moves must be made advisedly, with due regard for the sheep industry of the region as well as for the park.

23 See p. 34.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN PARKS

Glacier, Rocky Mountain, Grand Teton, and Yellowstone are the national parks of the United States proper which are most important in the conservation of large numbers of big game. Grizzly bear, bison, moose, and American wapiti, otherwise threatened with extermination, have been preserved within their boundaries. A herd of American pronghorn is receiving full and adequate protection at present in Yellowstone. Glacier has the finest representation of mountain goats, and it is the only place where this strange inhabitant of the highest crags is seen by large numbers of people. Bighorns are found in other parks, but only in this Rocky Mountain group are they abundant and frequently seen. Here are the beaver parks and the places where such fur-bearers as badgers and river otters are actually observed by visitors.

The west side of Glacier is a rain forest and resembles Mount Rainier in the Pacific Coast group, but the rest are typical of the Rocky Mountain region in general character and in flora and fauna.

GLACIER

That part of the Selkirk Mountains from which Glacier National Park has been carved is exceptionally rich in wild life. The lavish flora provides varied and abundant food and there are a wealth of animal habitats. Before it was reached by civilization this region contained representatives of all the large game mammals of temperate North America, inclusive of antelope, bison, caribou, mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk, moose, mountain goat, mountain sheep, mountain lion, wolf, and grizzly and black bears.

The history of human development has been kinder here than in many other parks. The region was inaccessible and remained relatively unknown for a long period. Consequently, its rich fauna did not suffer long hard years of exploitation such as decimated that of Rocky Mountain before it was rescued for park purposes.

The other side of the story is that Glacier suffers from poaching to a greater extent than any other national park, and under such circumstances that it can not be justly stopped. Under present conditions, a majority of the transgressors have a moral if not a legal right to what they take. The whole question is greatly complicated by lack of winter range and by the large number of private holdings within the park. Each side of the park has conditions peculiar to itself, and the solutions to the problems of one locality are in no way applicable to the others.

To the north, where the international boundary is the park line, the outlook is very favorable. When the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park24 becomes established, a real opportunity will be provided for administration of the combined parks as one faunal area. The boundary cuts arbitrarily through the heart of mountains which, from every natural consideration, are a unit area. The favorite goat haunts, bottoms frequented by moose, and habitats where caribou are most likely to occur lie astride this line. As it is the existence of Waterton Lakes Park has been a most fortunate circumstance for the wild life of Glacier. Much greater benefit would derive from the closer linking of the two as an international park, particularly as the favorable situation thus created might be expected to lead to a closer conformity of boundaries on the east and west.

The present eastern boundary of Glacier is also the west boundary of the Blackfeet Indian reservation. This line more or less severs the park game from its natural winter range on the Indian lands and cuts off the Indians from their ancestral food supply – the game in the mountains of the parks. The very designation of the boundary was the portent of trouble. Circumstance must take the blame. It would not be fair to place it upon either party to the conflict. Certainly the Indians who face starvation with the coming of every winter are not to be condemned if they step across the line and take for the gratification of hunger what the white man tries to conserve for the satisfaction of aesthetic longings.

From the park viewpoint there is no panacea for the wild-life problems along the eastern face. The boundary can not be pushed eastward to impinge much more heavily on the lands of the impoverished Indians. However, as an obvious administrative necessity it should be moved out to take in the small areas between its present position and the road which parallels this side from Glacier Park Station to the Canadian line. Such a boundary could be patrolled. It would be recognizable to everybody. All domestic stock could be effectively kept off park lands, thus giving the game the maximum use of winter forage within the park.

A second approach to the problem, and one which the superintendent has been ably forwarding, is that of conciliation of the Indians. In this undertaking he has become pioneer in a new and promising field. Looking into the future, the interests of park and reservation, far from being at variance, are seen to be surprisingly akin. It is to the greatest interest of the park that the Indians continue to contribute their presence with all the valuable appurtenances of their culture. They will degenerate and their arts crumble unless they can prosper and be self-sustaining. Hence the influence of the park should be directed in their favor wherever it is consistent with policy.

If the interest of these Indians can be stirred on the side of perpetuating the game for them and their descendants, and the danger of starvation among them can be averted, not only will they no longer be driven to poaching in the park but any that do transgress can be prosecuted with a free conscience. Best of all, the sympathies of their leaders will be with the law, without which there never can be effective enforcement.

The south boundary from Glacier Park Station to Belton is Theodore Roosevelt Pass, which follows these streams: Summit Creek east of the Continental Divide, and Bear Creek and the Middle Fork of the Flathead River down on the west side. The rule that streams make the poorest boundaries for wild life is nowhere better exemplified than here, where the railroad accentuates the evil. The whole length of the pass is occupied by the Great Northern Railway, and it can not be expected that all persons who travel have knowledge of national-park ideals.

Snows force the park game of this section down to the river bottom and the railroad, where it is greeted by poachers even before it crosses the line. Whereas the railroad practically limits the boundary from extension to its natural course along the crest of the Flathead Range and the headwaters of the South Fork of Two-Medicine Creek, the answer to this problem must be sought in a rigid system of patrol and perhaps feeding in an emergency to keep animals on the park side of the line.

On the west, the boundary follows the North Fork Flathead River from Lake McDonald to Canada. Again the disadvantage of bounding a faunal unit by a river which cuts through the winter range becomes evident, but this time there is another more immediate concern in the ranches which are privately owned and operated within the park.

These mountain ranches are not self-sustaining. The stock formerly ranged on the domain adjacent to the farms themselves, and the Park Service has been obliged to issue permits for the continuance of this practice. Not to do so would be to starve the ranchers out. Still, this use of the natural forage of the winter range has resulted in artificial feeding of the game, which is detrimental to the animals and a burden upon the park besides.

Further, these same ranchers were used to piecing out their living by utilizing the game for food in winter and by trapping for fur. It is not to be wondered that they have continued to reach for what they once considered part of their right of homestead. For this reason it is hard to secure a conviction even if a poacher is apprehended in this district. Existence on these marginal farms was always slim and the coming of the park has undoubtedly made it more precarious. There never will be a satisfactory solution of the problem until these private holdings are extinguished. This should be done promptly in fairness to all concerned. Otherwise, either the game must continue to suffer because of the incomplete adherence to park rules or the ranchers must be unavoidably harmed because of strict enforcement of those rules.

If this situation can be cleared up, the river may serve at least passably well as a boundary because it happens that a large part of the winter range of its drainage is on the park side. It only remains to make the forage on this range in the park properly available to the park's game.

AMERICAN BISON (Bison bison). – Abundant skeletal remains place the range of the bison well within the limits of the park. A skull and a number of leg bones were found by a member of the party near the head of Red Eagle Lake. The bison was the principal factor in the economy of the Blackfeet Indians and without it the pageant of life on the east side is sadly incomplete.

As a project undertaken by the park alone, the bison could never be brought back except as a paddock display. But there is genuine hope of building up a herd in joint ownership which will range in the park in summer and on the reservation in winter. If the Indians felt that the bison belonged to them, too, and knew that the annual increase would feed them in winter and provide them with the buffalo robes so dear to their lives and even to their religion, they might well be expected to guard the herd jealously.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN BIGHORN (Ovis canadensis canadensis). – The status of this species is generally satisfactory though its numbers fluctuate from time to time. They are choice food and there is no doubt that the Indians take some toll from them each year. Unless there should be an alarming decline in the total mountain-sheep population of the park, it would seem unnecessary to take any more drastic step than to guard as carefully as possible against poaching.

Certainly artificial feeding should be avoided entirely unless it becomes an absolute necessity. One of the many likely consequences of this practice was manifested at Many Glacier during the winter of 1931-32, according to a report of the superintendent. A band of sheep was being fed hay by the keeper of the hotel. They were enticed by the feed to abandon their usual caution and their safe retreats, with the result that a number of them fell prey to coyotes. There is no end to the complications when wild animals are made dependent upon man.

FIGURE 43. – A number of mountain sheep from this Many Glacier band fell prey to coyotes at the feed yard. This is one of the many complications resulting from artificial feeding. Photograph taken September 1, 1931, at Many Glacier, Glacier. Wild Life Survey No. 2394 |

MOUNTAIN GOAT (Oreamnos americanus missoulae). – This animal seems to be as secure in Glacier as could be desired. Its relationships in the matter of presentation to the visitor are ideal. Everyone who so wishes can see these strange creatures on the precipitous rocks that are home to them. Yet there is just enough uncertainty as to where and when to go to give zest to the chase. Exercise afoot or on horseback is required, and the successful hunters have stories to tell in the hotel lobby at night.

FIGURE 44. – Mountain goats at Cracker Lake. Presentation here is ideal, as everyone willing to walk or ride can obtain views of this animal on the rugged cliffs that are its native home. Photograph taken September 3, 1931, in Glacier. Wild Life Survey No. 2071 |

AMERICAN PRONGHORN (Antilocapra americana americana). – Vernon Bailey25 believes that antelope were originally present in this vicinity. There would be no likelihood of having them in the present park in a free state, and their presentation in an inclosure would be subversive of national park standards.

MOOSE (Alces americana). – Moose are not common in the park now, but, whereas they were very scarce a few years ago, they are reported by everyone as steadily increasing. The best moose country is on the west side in the vicinity of the private ranches discussed above. Their improving status is undoubtedly due to the decrease of poaching, but they still suffer somewhat from this cause. That they are still hunted was attested by their wildness when sought out by a member of the party. When the private holdings are eliminated, this problem will be solved and moose will undoubtedly become one of the familiar sights of the park.

AMERICAN WAPITI (Cervus canadensis canadensis). – As is the case in each of the parks where elk are found, the critical factor is one of winter range. There are two herds in the park which probably intermingle in the summer in the vicinity of Triple Divide. The smaller St. Mary herd of the east slope, now comprising about 70 head, is in constant danger of being annihilated whenever a heavy winter forces the animals out onto the Indian reservation. This very occurrence brought about a slaughter a few years ago and the herd has not fully recuperated since. The situation would be greatly helped if all domestic stock could be kept off the winter range around St. Mary Lake in the park to restore its full carrying capacity for the native game.

The larger herd of elk, numbering perhaps 300, is in the Nyack district. It suffers from poaching along the railroad when it is forced down from the heights in winter. These elk were found frequenting a lick on Coal Creek within 2 miles of the boundary in August. As suggested above, patrol will have to deal with this problem as well as it can. The boundary is bad for game and can not be moved to the top of the watershed to the south.

WESTERN WHITE-TAILED DEER (Odocoileus virginianus macrourus) and ROCKY MOUNTAIN MULE DEER (Odocoileus hemionus hemionus). – Both forms are found in the park in numbers, though the white-tailed deer are by far the commoner. The mule deer belong more to the interior high country and there is no question concerning their status.

The white-tails are the common deer of the west side, which contains many square miles of ideal habitat for their kind. At Logging Creek, where they are artificially fed, some 300 were reported in the winter of 1930-31. The reason given for this practice was the scarcity of forage due to heavy grazing of the range by ranchers in the park. As suggested above, there is only one real solution and that is to buy out the ranchers.

Even under present conditions there is question as to the advisability of the winter feeding, with its tendency to accentuate yarding of large numbers of deer, to concentrate coyotes, etc. The deer are, if anything, too abundant in this section, considering that the forage is used by domestic stock as well. If deer continue to increase, serious damage to the range may ensue. It would be better to keep their numbers even below normal to preserve the carrying capacity of their range until such time as the domestic stock is removed.

MOUNTAIN CARIBOU (Rangifer montanus). – Caribou can not be considered as a member of the Glacier Park fauna at the present time its occurrence being limited to an occasional straggler in the Kintla district in the extreme northwest corner. Undoubtedly mountain caribou have frequented the area to a greater extent in the past, but it is the very fringe of their range. A few are still found in the United States further to the west in Montana and northern Idaho near the Canadian line.

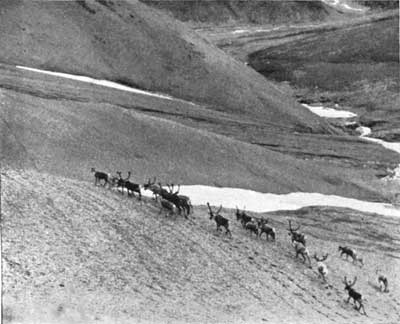

There is little likelihood that this wandering animal of the north can ever be made a permanent resident of the park, but there is a hope that rigid protection in the adjacent national forests, including the Kootenai, Pend Oreille, and Blackfeet, will favor its increase in this country. If the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park is established, a cooperative effort to improve the status of this caribou on both sides of the international boundary would be a worthy project. If successful, the mountain caribou might be a frequent enough visitor in Glacier Park to merit a real place in its fauna.

CANADIAN BEATER (Castor canadensis canadensis). – That the beaver population is kept to the minimum, particularly on the west side, is evidenced by the large number of old workings and the very small amount of fresh cutting. Because of the manner in which they are taken, it can not be expected that poaching of beaver will ever be stopped until private holdings are eliminated, and an improved sentiment toward the park wild life is adopted by the inhabitants of the surrounding regions.

PREDATORS. – The status of these secretive animals in this park is not very well understood and should be carefully investigated. The coyote is abundant, probably more so than in primitive times. But if mountain lion, wild cat, Canada lynx, and gray wolf are no longer present in normal numbers, then the coyote is filling their place as the natural control of the herbivores and should not be controlled except in the event of an emergency. The ultimate goal should be to have all the native predators present in reasonable numbers, which would probably mean an increase of mountain lions, a restoration of that rare animal, the wolf, and a decrease of the coyote in proportion. The present situation should not be interfered with until adequate studies are made.

MUSTELIDS. – All members of this family should be encouraged and protected as carefully as possible, the more because they are persecuted everywhere outside the parks. Mink, marten, and weasel are probably safe. Badgers do not find suitable habitats in the park, though two were observed in an old burn on the west side near the North Fork Flathead River. The wolverine is probably gone. If it fails to come back it could be reintroduced some day. The fisher is native and may still be present, though no one could tell us anything about it. It is so insistently trapped and has become so rare in the United States that a valuable service would be rendered if it should came back in Glacier under rigid protection.

BLACK BEAR (Euarctos americanus). – Whereas black bears are fairly common, they are not encouraged to become tame. Hence there is no serious bear problem. On the other hand, they are thoroughly enjoyed by the visitors. For instance, when a bear appeared at McDermott Lake all the occupants of the dining room at Many Glacier Hotel rushed to the windows. Bears are most attractive when the contact is not too intimate.

GRIZZLY BEAR (Ursus horribilis sp.). – These occur at high altitudes and are rarely seen even by the rangers. This is the only park in the United States besides Yellowstone where this vanishing species is found, and it should be jealously guarded.

TRUMPETER SWAN (Cygnus buccinator). – Though trumpeters nested in this part of Montana until very recently, no suitable nesting lakes were seen within the park boundaries. One of the few specimens of trumpeter swan in existence is from St. Mary Lake,26 but the park waters probably never figured except in the migrations of this species. It can not be hoped that Glacier Park will be one of the places where the trumpeter can be saved.

SANDHILL CRANE (Grus canadensis tabida). – The sandhill crane has gone from the park as a nesting species. Its return is most unlikely.

FISH-EATING BIRDS. – This question has been discussed in relation to Glacier on pages 65-66.

24 Since this manuscript was prepared, the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park has been established.

25 Wild Animals of Glacier National Park, by Bailey, Vernon, and Bailey, Florence Merriam, 1918, p. 31.

26 Life Histories of North American Wild Fowl, by Bent, Arthur Cleveland. United States National Museum, Bulletin 130, 1925, p. 295.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN

Rocky Mountain is another of the mountain-top parks. The failure of the east boundary to provide winter range was discussed as a typical example of this class of problem on pages 40-41. A similar situation exists on the west side of the park.

The west boundary, until recently, lay along the Colorado River, which is no more than a mountain brook a few feet across at this point. Deer and elk naturally drifted down the Colorado River valley in the fall, where they were easy prey during hunting season. The river could be easily crossed and was no barrier. It was like having stock in an open field, in one-half of which they were protected and in the other half of which they could be shot. A portion of this boundary has been improved by extending it to the crest of the Never Summer Range on the west side of the Colorado River. This mountain crest is a natural barrier to the wild life of the park. However, the Never Summer Range extension covers only about one-third of the western boundary. To complete the protection of the winter range on the west side of the park, the west boundary should be continued from the crest of the Never Summer Range south along the crest of Parika Peak, Cascade Mountains, and the Blue Ridge, to include the sage fiat down by Table Mountain. The sage fiat country would serve as the "lowest zone inhabited by the majority of the park fauna" in this section of the park. Of course, members of the mountain fauna may have migrated farther down the valleys on both east and west sides of the park in earlier days, but the extensions outlined here for both sides of the park would greatly alleviate the present unsatisfactory condition.

The protest is apt to be made at this point that the process of establishing natural boundaries, as outlined above, is a vicious logical process without an end. That is, the boundary was first along the Colorado River, then it was moved to the crest of the Never Summer Range in order to protect the fauna along the Colorado River; next, there would be a clamor to extend it to the west base of the Never Summer Range in order to protect the fauna of the Never Summer crest, and so on ad infinitum – or as long as anyone wanted to enlarge the park. It would be argued that whatever boundary was ultimately chosen would be an arbitrary choice, and, therefore, why not be satisfied with the present arbitrary boundary?

| FIGURE 45. – Accelerated erosion is one of the harmful effects of overgrazing. In this valley of Estes Park, the fertile bottom is being carried out bodily and at a rapid rate. Photograph taken June 22, 1931, in Estes Park, Rocky Mountain. Wild Life Survey No. 1992 |

While it is true that any boundary chosen is an arbitrary boundary, the only justifiable arbitrary boundary is one which follows a natural boundary. Nor is this a vicious process of territorial acquisition. Its purpose is to adequately safeguard the park fauna as the minimum cross-section of a biological unit which can be safely maintained. Beyond that, there is no need for further extension along the arguments just developed.

The necessity for extending park territory in certain places is not limited to the need for winter range alone. It is closely tied up with all the difficulties arising from influences external to the parks. In areas so small as our individual national parks, unless they are adequately protected by natural boundaries it is impossible to preserve the species blacklisted outside. It is impossible to preserve the valuable fur-bearers. It is impossible to check the encroachment of exotic species or to preserve intact the species native to the park. In fact, the nature of boundary difficulties is of such fundamental character that without adequate territory in our national parks and proper natural boundaries to protect them the whole national-park project must fail to fulfill its purpose.

BLACK BEAR (Euarctos americanus). – Black bears are increasing in the park. With their increase in numbers and further development of the region for summer homes, their depredations are bound to increase. There has been no problem in the past because bears, as well as many other forms of wild life, wore almost exterminated in this region 30 years ago. Under park protection the wild life is coming back, and in its old haunts summer homes and commercial developments are to be found. It is inevitable that difficulties will arise where bears and elk are placed in the highly complex and fragile environment of the summer resort. Houses and fences are flimsy; they are not built to withstand the attacks of bears and elk. People are not accustomed to these wild animals in their civilized communities, and they do not know how to defend themselves under such unusual circumstances. For the future there seem to be but two courses from which to choose – either bears and all other large animals must be kept to the minimum or else the private holdings in the heart of the park must be acquired and converted into natural park territory. If a national park is to be there at all, the latter course is the only justifiable one as well as the only ultimate solution. Other reasons for the acquisition of this territory have already been presented in the discussion on providing adequate winter range.

Fortunately, there is no bear feeding at Rocky Mountain, and the bears are still wild. It is hoped that this condition can be maintained.

GRIZZLY BEAR (Ursus shoshone). – (The type locality of this grizzly is Estes Park, but there may have been other forms in the park.)

The grizzly bear is probably gone from this region. There has been a recent report, unconfirmed, that grizzly tracks were seen in the Never Summer Mountains in the northwest corner of the park. Under present conditions, it would be undesirable to reintroduce the grizzly bear, even if such were possible.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN MARTEN (Martes caurina origenes). – Martens are not scarce in the park, but they need absolute protection from poaching. Trap lines have been found within the park, and martens actually found in the traps. Poaching is persistent in Rocky Mountain and will be difficult to eliminate completely.

FISHER (Martes pennanti pennanti). – There is no record of fisher. Probably the park is south of its range.

WOLVERINE (Gulo luscus). – See pages 44-46.

OTTER (Lutra canadensis sp.). – Otters may have been transients in the park at one time. They are gone now. There are records of their having been taken at various points throughout the State, including a record near Grand Lake, but nowhere in Colorado have they ever been abundant. The reason for this scarcity is not definitely known. But with these facts in view, it would not seem advisable to attempt to reintroduce them in the park until more definite information is gathered concerning their suitability to the region.

TIMBER WOLF (Canis nubilis). – In former years wolves were abundant throughout the State. For many years they have not been seen or heard of in the park. Recently, a few reports from various sources would indicate that perhaps a few have persisted or migrated into the park. All carnivores, except weasels and coyotes, are very scarce in the park, for which reason the wolves, if present, should not be discouraged.

MOUNTAIN LION (Felis oregonensis hippolestes). – Mountain lions have been systematically hunted in the region for many years. Perhaps a few remain. There has been a double bounty paid for mountain lions, amounting to $75 per head. Given the complete protection of the park, they should be able to reestablish themselves over a period of years. It should be noted here that the park administration has carried out no control of predators for many years, and is in full accord with the desire to have them reinvade to the carrying capacity of the range.

CANADA LYNX (Lynx canadensis canadensis). – We could get no recent records of lynx in the park, although they were abundant at one time throughout the high mountains of the State, even south into the San Juan and Sangre de Cristo ranges. They have been greatly reduced – a few may still remain in various parts of the State. They belong naturally in the park fauna. The problem at present, however involves the status of all the other high mountain forms of life – valuable and scarce forms such as grouse, ptarmigan, mountain sheep, and snowshoe rabbit. It is not known why ptarmigan and grouse, for instance, are so scarce. However, the present status of the lynx in the park must be reckoned as a change from the original picture.

GROUND SQUIRREL (Citellus elegans). – This little ground squirrel has profited by civilization to the extent that it has invaded the Estes Park country by the thousands. It has become a nuisance around buildings, gardens, and in fields, and appears to be displacing the native and more colorful golden-mantled ground squirrel (Callospermophilus lateralis). This is one of the outside factors affecting the park fauna and should be thoroughly studied for solution.

BROAD-TAILED BEAVER (Castor canadensis frondator). – Beavers are abundant throughout Rocky Mountain National Park. They cause no difficulty except where they obstruct the local water supply on one of the private holdings. One private resort trapped six beavers from its domestic water supply three years ago, and has had no difficulty since. While this is not exactly in accord with park aims, it is obviously necessary where private holdings are within the park. It is only one of the complications which ensue so long as a park embodies private lands within its boundaries. This type of difficulty arises from the inadequacy of the park rather than from the presence of the animal itself.

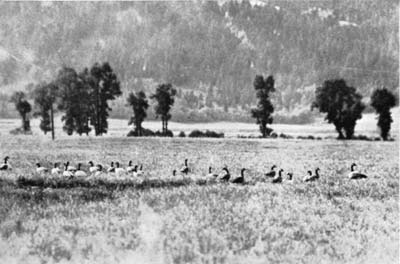

FIGURE 46. – Many different forms of wild life, ranging from small aquatic insects to waterfowl, muskrat, mink, and even moose, follow the successional habitats produced by the beaver cycle. Photograph taken July 13, 1931, at Jackson Hole, Wyo. Wild Life Survey No. 2130 |

Another problem which has arisen is in connection with the presentation of animal life. Beavers have been present in Hidden Valley for at least 30 years. Recently, the new Transmountain Highway has been developed through Hidden Valley, passing the beaver lakes en route. This provides an excellent opportunity for visitors to see beaver colonies from the highway. It so happens that the beavers have nearly exhausted their food supply – the aspens and willows – by their lakes. In a few years they must desert these lakes by the new highway and go elsewhere. The opportunity of seeing these particular beavers will be lost to thousands of visitors. Only the dried and revegetating lake beds will remain to tell the story. It has, therefore, been suggested that the beavers be limited to one family in order that the food supply may be adequate to maintain them, and that they may always be present to be seen from the road.

If the suggestion is worth making, it is worth considering.

A beaver is not just an animal which builds houses and dams. It is an animal which moves into a region increases in numbers until it exhausts its food supply, then moves elsewhere. Vegetation gradually reinvades the deserted pond, and the whole cycle of plant succession is repeated until suitable beaver food is once more produced, beavers move in again, and the whole cycle starts over. This is the way much of our meadow land has been formed. Many different forms of wild life, ranging from small aquatic insects to waterfowl, muskrat, mink, and even moose, follow in succession the changing habitats produced by the beaver cycle. No individual phase of the beaver cycle is more destructive or more climax than the rest; it is a continuous chain of plant and animal succession, each phase of which leads naturally to the succeeding steps; any one moment in the cycle signifies all the rest. It is this marvelous change, variety, and orderly succession of nature which makes nature what it is. It is this for which man comes. It restores in him a certainty, which he needs. This is recreation, and it is the great value of the national parks. While this may seem a long step from the beavers of Hidden Valley, they nevertheless are an integral part of the complex chain, and they have been considered so important a part that it has been suggested that they be changed and controlled for the sole purpose of enhancing their value in the chain. But if they were controlled, there would be nothing left except the interesting animal which builds houses and dams in its picturesque lake – a new thrill on the new mountain road. If there is to be any permanent value in our parks, they must be allowed to run their orderly succession of change which produces the marvelous variety of life.

FIGURE 47. – Beavers at Hidden Valley have utilized the aspen near at hand and now travel a well-beaten path to a more distant grove. The farther they must go overland the greater exposure to natural enemies. It is at least possible that the balance between population and food supply is assisted by this relationship. Photograph taken July 1, 1931, in Rocky Mountain. Wild Life Survey No. 1823 |

AMERICAN WAPITI (Cervus canadensis canadensis). – The elk situation has been presented, pages 40-41.

One other range extension, treatment of which was not necessary to the former discussion, is suggested here. About 100 elk summer above Cow Creek Canyon and winter on the ranch and below it. If the park boundary were extended to include the ranch and about 3 miles of the valley territory south of the ranch, this would be the one place along the east side of the park where the necessary winter range could be provided without bringing elk around the centers of human habitation.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN MULE DEER (Odocoileus hemionus hemionus). – The deer winter range is so closely related to the elk winter range that it needs no further treatment here.

AMERICAN PRONGHORN (Antilocapra americana). – Antelope ranged up into the foothills and mountain parks in the past. The fringe of their range may have extended into the present park territory, but there seems to be no suitable all-year range for them within the park at present.

BISON (Bison bison). – Skulls have been found even up to timber line in the park. There would be no possibility of maintaining bison on the present limited range of the park. They are also gone from the original faunal picture of the park.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN BIGHORN (Ovis canadensis canadensis). – See pages 51-52. The mountain sheep of the park are adequately protected. They have suffered heavily from scab in the past, and some of them appear to be still infected. Their situation needs careful investigation. They seem to be maintaining themselves.

In general, Rocky Mountain is a park which suffers greatly from problems due to early influences, problems of geographical origin such as improper boundaries and inadequate winter range, and problems of human and animal conflict. Yet it is a park with tremendous possibilities for faunal development. But before these possibilities can be fully realized, the boundary adjustments will have to be made, and the private holdings eliminated. Even one last unfortunate claim must be removed some day, and that is the canal which takes the normal supply of water from the Never Summer Mountains and Specimen Mountain so that even fishing is spoiled in the streams below.

YELLOWSTONE AND GRAND TETON

These two parks are treated together because their animal problems are not separate. It is to be greatly regretted that Yellowstone when originally established did not include the Thorofare Plateau and the intervening territory to the Teton Mountains, as well as sufficient winter range on both north and south sides of the park. Perhaps this seems an extravagant concept. But let it be recalled that Jasper Park in Canada has an area of 5,380 square miles – the approximate equivalent of Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Grand Canyon National parks combined. More than this, Jasper is contiguous with three other national parks, forming, in reality, one large park with an approximate area of 10,000 square miles, extending continuously along the Canadian Rockies for a distance of over 250 miles. There is not one national park in the United States which provides adequate range for its animal life. In a country expanding and developing as fast as ours there is great need for at least one area which will be adequate to protect and maintain a sample of our native wilderness life as a national heritage for all time.

FIGURE 48. – One of the newest parks takes steps to prevent destruction of the natural lake shores. Note old auto tracks now cut off by log barriers. Photographs taken July 9, 1931, at String Lake, Grand Teton. Wild Life Survey No. 1920 |

The wild life of the Yellowstone-Teton area could be served best if the park were composed as follows:

From Eagle Peak, continue the east boundary of Yellowstone along the crest of the Absaroka Range to the point at which the Wind River highway, U. S. 87-W, crosses this crest; follow said highway westward to the Buffalo Fork of the Snake River; follow Buffalo Fork westward to the west boundary of the Teton National Forest; then continue southwestward along the west boundary of the Teton National Forest to a point approximately east of the southmost point of Grand Teton National Park; then west to the Idaho-Wyoming boundary, and north along this boundary to the Bechler River corner of Yellowstone Park.

In addition to the present Yellowstone and Teton Parks, this unit would include the Thorofare Plateau, the intervening summer game range west to Jackson Lake; the great wild fowl and moose breeding grounds in the Jackson Lake region itself, and would provide protection for fur-bearers and winter range for mountain sheep in the Tetons. More than this, it would provide one park unit in the United States sufficient in area and habitats to maintain the forms of animal life which can not exist anywhere else nor under any other conditions.

For many years the absolute necessity of providing winter range on the north side of the park has been so apparent that there is no need of treating it here. It is to be hoped that the purchase of this winter range will be consummated without delay because of the pressing need for winter forage and the maladjustments resulting from congestion of game at the present feeding stations.

It would be useless to detail each species of animal in the park more has been published about the wild life of the Yellowstone region than for any other park. The main types of faunal problems affecting the park as a whole have been treated throughout the previous part of this report. In fact, there is not a single type of problem discussed thus far which does not apply to Yellowstone. Nowhere in the national-park system is the unit character of the area more evident. To make the park coextensive with this unit faunal area would be to remove the fundamental cause of most of the difficulties. Then there should be a thorough investigation of the status of each species to determine the immediate factors operating to the detriment of the animal, and to devise means of correcting them. Of course, the problems of conflict between man and animal would still persist, though not to the same extent. To outline every type of faunal problem in Yellowstone would be to recapitulate discussion which has gone before. But an indication of the most immediate work to be done might be advantageous.

The bear problem was outlined, pages 68-70 and 82-84. In accord with the suggestions given there, an investigation is to be inaugurated.

FIGURE 49. – In our experience, the grizzly will not leave its path to harm a human being; neither will it brook interference with its family life. Photograph taken September 13, 1929, at Canyon Lodge, Yellowstone. Wild Life Survey No. 509 |

The fur-bearers can be advantageously treated as one problem. The status of the wolverine has already been outlined (pages 44-46), but there should be a thorough investigation of all the factors affecting the fur-bearers of the two parks to determine whether they are increasing or dwindling, and why; what effect they have upon rare wild fowl of the parks; whether they themselves need assistance or whether they are menacing some other form of life which is in danger of extinction (for instance, sandhill crane or trumpeter swan). In general, the fur-bearers' plight should be known thoroughly in order that they may be maintained in their normal position among the fauna of the region.

The spread of the coyote has already been treated (pages 47-49) and its present control in Yellowstone advocated. However, there is need of definite information about the coyote to know exactly what it is doing to the rest of the park game, i. e., the extent of its winter kills, its menace to all ungulates and ground-nesting birds during breeding season, whether it is responsible for the precarious status of antelope and mountain sheep in the park, whether it is displacing other fur-bearers, or whether its damage is greatly overestimated. The complete role of the coyote in relation to the park fauna should be definitely known as soon as possible.

The wolf is gone; but if suitable range and protection could be procured for all native animals of the park, the wolf might then have a place.

Mountain lion and lynx have been controlled in past years until their present status is doubtful. The same investigation outlined for the coyote should be undertaken in relation to mountain lion and lynx, with the view of determining exactly what their status is in order that any further management may be conducted advisedly.

The white-tailed deer is gone. Before any attempt is made to bring it back, there should be thorough study of its habitat in and near the park. If the park was only the fringe of its range, it might be very unwise to attempt to reestablish it unless it could be self-sustaining, or until enough of its range could be procured.

Elk, deer, sheep, and antelope, as well as the buffalo, are all sustained in winter by artificial feeding. The undesirable phases of this practice and the possibility of its harm to the animals have already been pointed out. Nevertheless, winter feeding is absolutely necessary as a present emergency measure and until adequate winter range is provided. The present available winter range already shows unmistakable signs of overgrazing. It would be inadvisable under these circumstances to increase the elk herds until range conditions can be improved. The carrying capacity of the range must be ascertained and the elk held within this limit. Mr. M. W. Talbot, senior forest ecologist, California Forest Experiment Station, and Mr. George F. Baggley, chief ranger, Yellowstone National Park, have both pointed out the necessity of an immediate range reconnaissance being conducted in the Yellowstone winter-range area. With the original character of the range becoming more obscure each year, the urgency of this investigation can not be overemphasized.

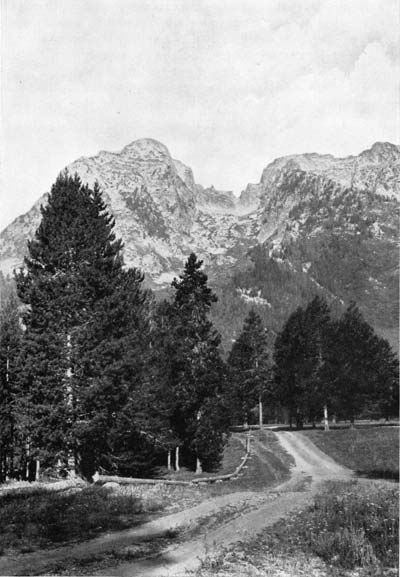

FIGURE 50. – Canada geese adjust themselves to man's presence in Yellowstone and flourish in large numbers. The wary sandhill crane, on the contrary, shun the developed sections. Photograph taken September 18, 1929, in Lamar Valley, Yellowstone. Wild Life Survey No. 385 |

Concerning the animals themselves, Mr. W. M. Rush, formerly in charge elk study, and Mr. O. J. Murie, biologist, Bureau of Biological Survey, have both conducted extensive investigations of the elk herds in the region. But further research is necessary to determine the factors limiting mule deer, antelope, mountain sheep, and moose in these two parks. Especially is the status of the latter three obscure. They are so rare over most of their former range in this country that their protection in this region is vital. The mountain sheep of the Tetons, according to Superintendent Woodring, normally range on the west side of the peaks because the prevailing winds keep this side free from snow. However, this area is occupied by domestic sheep, and the mountain sheep are forced to exist in the remaining unsuitable range. If the Teton boundary extended to the Idaho line, as has been suggested, this unfortunate situation would be corrected.

FIGURE 51. – The pronghorn stands on the horizon in Yellowstone. At present it barely holds its own under adverse winter range conditions. Photograph taken June 26, 1930, at Lamar River, Yellowstone. Wild Life Survey No. 852 |

The status and investigation of the trumpeter swan is outlined, pages 28-31.

Five pairs of sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis tabida) were seen in the region last summer. Two pairs were known to nest in Yellowstone Park. A nest with two eggs was found in the Bechler River region, and a pair of adult cranes with one young were seen by Tern Lake. This is by no means a complete census, but it is at least a definite record. The same research outlined for trumpeter swans should be conducted for sandhill cranes.

The problem of the American white pelican in Yellowstone has been outlined, pages 78-79. There should be a complete investigation of the fish-parasite relations in Yellowstone Lake. Notable work has been done by Maurice C. Hall, Henry B. Ward, and Lowell A. Woodbury. But the importance of mergansers, ospreys, gulls, cormorants, grebes, bears, and other fish-eating animals has not yet been determined in relation to the pelican problem. Further work needs to be done. After all, the parasite problem might not be solved by removal of pelicans from Molly Island.

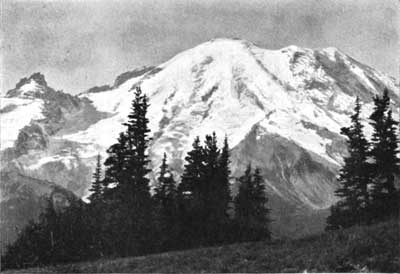

PACIFIC COAST PARKS

Crater Lake, Lassen Volcanic, Mount Rainier, General Grant and Sequoia, and Yosemite are the national parks of the high mountain ranges that fringe the Pacific Ocean. Except for Mount Rainier, which is in the humid north coast belt and is consequently clothed with dense rain forest, the parks of this group have striking biotic similarities. This in turn is due to broad similarities in geography and climate.

Coastal forms occupy their gentle western slopes, which have a moderate and moist climate because of exposure to oceanic influences. The eastern slopes of these mountains are more rigorous in every aspect. The escarpments are precipitous. Temperature fluctuations are extreme and the country is arid. In short, the eastern slopes are typically Great Basin, and Great Basin forms predominate.

The faunal problems of all parks in this group are alike: First, because many of the same species are concerned; second, because the history of human development has been much the same for all of them; third, because they show the same geographic limitations in failure to include the lowest life zone occupied by their faunas; and, fourth, because they are all subject to the same type of development for human use.