|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 7 The Wolves of Isle Royale |

|

STUDY AREA

MICHIGAN'S Isle Royale, in Lake Superior, is 50 miles northwest of the Keweenaw Peninsula and about 20 miles southwest of the Canadian shore (89° west longitude, 48° north latitude). Forty-five miles long and 2 to 9 miles wide, the 210-square-mile island parallels the north west shore of the lake (figure 2). The nearest mainland is Prince Location, Ontario, 15 miles northwest of the southwest end of the island.

Figure 2—Isle Royale

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

In 1940, Isle Royale became a National Park, insuring the preservation of its wilderness character. Copper mining (prehistoric and modern) pulpwood cutting, hunting, fishing, and trapping had been carried on to some extent before 1940. Since then, however, Isle Royale has been protected from such disturbing influences except fishing (commercial and sport).

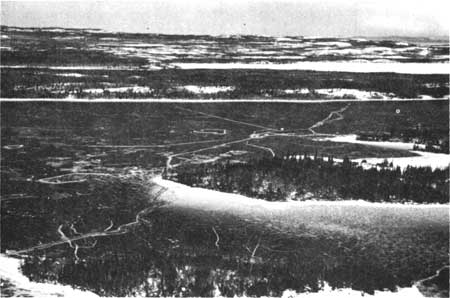

Although there are no roads in the park, approximately 100 miles of little-used foot trails provide access to most of the interior (figure 3). Bays and harbors enable boaters to explore some of the periphery, but much of the shoreline is rugged and unsuitable for mooring boats. Rock Harbor Lodge at the northeast end of the island and Windigo Lodge at the southwest end are the centers of tourist activity. (Summer headquarters of the National Park Service are on Mott Island.) Between these areas are two ranger stations, three forest-fire lookouts, and a few isolated abodes of commercial fishermen. The tourist season extends from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Park Service staff and resident commercial fishermen live on the main land from December to April.

Figure 3—Main foot trails of Isle Royale

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Physiography

The topography of Isle Royale is characterized by series of parallel ridges and valleys, narrow points and bays, numerous nearby islands, and slender lowlands and lakes. The island originated when a bed of pre-Cambrian lava and sedimentary layers faulted, tilted upward from southeast to northwest, and protruded from the sea. Erosion, submersion, and deposition of Cambrian sediment followed, and the process was repeated. "Similar processes continued until the marked elevation of the land, which took place at the close of the Tertiary, and which initiated the repeated glaciations of the Ice Age" (Adams, 1909:32).

The last (Wisconsin) ice sheet completely covered Isle Royale by several thousand feet. After it receded, Lakes Duluth and then Algonquin covered the island. Eventually, new outlets developed and the lake level dropped by steps, as evidenced by the ancient beach lines seen today on Isle Royale and the north shore of Lake Superior (Adams, 1909). The present lake level is 602 feet.

Because of the direction of the original tilting, the southeast sides of most ridges slope, whereas the north west sides form escarpments. One main central divide, the Greenstone Ridge, extends the length of the island. Its summit, Mount Desor (elevation 1,394 feet), is the highest point on Isle Royale. Minong Ridge and Red Oak Ridge parallel this on the northwest and southeast, respectively. These and numerous lesser crests produce a "washboard effect." At the northeast end of the island, ridges project for miles into the lake, forming points, peninsulas, and over 200 surrounding islands (figure 4).

Figure 4—Aerial view of northeast end of Isle Royale.

Figure 5 —Northward view of the south-central section of

Isle Royale, well used by wolves every winter.

The soil is shallow, sandy or stony loam; there is little glacial till. Postglacial disintegration of rock, plus deposition of organic remains, has produced most of the soil, but lacustrine clay and sand are present in isolated locations (Adams, 1909). Erosion has left many ridgetops bare or covered with thin, azonal soil, whereas deposition has built up many poorly drained valleys. Where accumulation has occurred in upland areas, there has been light podzolization (Linn, 1957).

Between the ridges there are hundreds of ponds, swamps, and bogs, and approximately 30 lakes. Siskiwit Lake, the largest, is 7 miles long and 1-1/2 miles wide. Most watersheds are small, so many streams are intermittent; the few permanent ones are slow-moving. Numerous narrow bays, harbors, and channels interrupt the shoreline, particularly along the northeast half of the island. In winter, these frozen waterways provide landing fields for the research aircraft and travel routes for wolves. The 200-mile shoreline is also a favorite wolf travelway.

Climate

The climate of Isle Royale is similar to that of the rest of the upper-Great-Lakes region. Some snow may be expected any time from September to May, but it accumulates only from mid-November to April. Temperatures are moderated by Lake Superior, especially on Isle Royale, where daily lows in winter may be 6° warmer than those of the mainland. In summer Isle Royale is much cooler than the mainland. Trees are not fully leaved until about June, and traces of autumn color appear in late August.

Weather records for Isle Royale are incomplete, for in most years no one is there from December to May. Table 1 gives the data recorded at Mott Island, near the northeast end of the park, from 1940 to 1952. Since snowfall records are unavailable for Isle Royale, data are presented from the nearest other U.S. Weather Bureau station, Grand Marais, Minn., approximately 36 miles west of the southwest end of the island (table 2).

TABLE 1.—WEATHER RECORDS FROM MOTT ISLAND, ISLE ROYALE, 1940-52

[U.S. Department of Commerce, 1956a]

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | June | July | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec.a | |

| Mean total precipitation (in.) | 2.31 | 1.86 | 2.12 | 2.27 | 2.19 | 3.58 | 2.81 | 3.34 | 3.99 | 2.35 | 2.68 | 1.52 |

| b(3) | (3) | (3) | (4) | (10) | (12) | (12) | (12) | (11) | (10) | (9) | (4) | |

| Mean snowfall (in.) | .... | .... | .... | .... | .8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .4 | .9 | 12.2 | .... |

| Mean temperature | .... | .... | .... | .... | 45.2 | 52.2 | 58.3 | 60.5 | 52.9 | 44.6 | 30.9 | .... |

| Mean maximum temperature | .... | .... | .... | .... | 54.4 | 61.1 | 67.5 | 68.1 | ? | 51.4 | 35.8 | .... |

| Mean minimum temperature | .... | .... | .... | .... | 35.8 | 43.0 | 49.0 | 52.8 | 46.1 | 37.8 | 26.0 | .... |

| Maximum temperature | .... | .... | .... | .... | 79 | 86 | 87 | 86 | 81 | 72 | 62 | .... |

| Minimum temperature | .... | .... | .... | .... | 19 | 33 | 37 | 38 | 29 | 12 | 7 | .... |

aAnnual precipitation 1941: 30.69; 1942: 35.68 (only years available) bNumber of years on which mean is based. All other figures based on 10 years. | ||||||||||||

TABLE 2.—WEATHER RECORDS FROM GRAND MARAIS, MINN., 1931-52

[U.S. Department of Commerce, 1956b]

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | June | July | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Annual | |

| Mean totala precipitation (in.) | 1.53 | 1.01 | 1.40 | 1.90 | 2.53 | 3.48 | 2.72 | 3.07 | 3.06 | 2.25 | 2.02 | 1.36 | 26.33 |

| Meanb snowfall (in.) | 14.3 | 12.8 | 9.4 | 5.4 | .1 | Tr. | 0 | 0 | .1 | .9 | 7.9 | 12.9 | 63.8 |

| Meanc temperature | 15.2 | 16.1 | 25.0 | 36.3 | 45.5 | 51.7 | 58.5 | 61.1 | 54.2 | 44.1 | 30.7 | 20.4 | 38.2 |

| Mean maximumc temperature | 24.4 | 25.4 | 33.2 | 44.5 | 55.0 | 61.9 | 69.2 | 9.8 | 62.2 | 52.0 | 37.7 | 28.6 | 47.0 |

| Mean minimumc temperature | 6.0 | 6.8 | 16.9 | 28.2 | 35.9 | 41.7 | 47.9 | 52.7 | 46.2 | 36.2 | 23.7 | 12.1 | 29.5 |

| Maximumd temperature | 48 | 51 | 63 | 70 | 85 | 88 | 94 | 96 | 86 | 72 | 62 | 55 | 94 |

| Minimumb temperature | -34 | -34 | -24 | 5 | 17 | 25 | 28 | 33 | 23 | 6 | -13 | -27 | -34 |

aBased on 21 or 22 years. bBased on 19 years. cBased on 20 years. dBased on 18 years. | |||||||||||||

Figure 6—Greenstone Ridge (in background) which runs

the length of the center of the island, as seen from the north.

Microclimates in the interior of Isle Royale differ significantly from those along the shore. Robert M. Linn (1957:96—97) in a study of the island's climax forests and their microclimatological differences found that ". . . in areas near to Lake Superior, temperatures are lower and have less range, and atmospheric moisture is greater than at the higher elevations in the center of Isle Royale. Here temperatures are highest and atmospheric moisture is lowest. These two extreme habitats possess climatic patterns which differ enough to be expressed by different climax vegetation types."

During the present study, the February—March snow depth on the level in wind-protected areas was 16 to 24 inches in 1959, 12 to 16 inches in 1960, and 20 to 26 inches in 1961. Drifts on the northwest sides of ridges were 3 to 6 feet deep, but exposed southeast slopes and thick swamps often had less than a foot of snow. Hakala (1953) reported snow depths of 18 to 36 inches for a similar period in 1953.

By January, extensive sheets of floating ice surround Isle Royale on calm days; during windstorms these break and wash up on shore. This action keeps the lake open south of the island, but a shelf forms along the shoreline and across the smaller bays. In 1959 and 1961 all the harbors and bays (including Siskiwit Bay) were frozen their entire lengths by February. Similar conditions were not encountered in 1960 until March.

During 1959 and 1960 ice often appeared to connect Isle Royale with Canada, but after each high wind the ice span disappeared. However, in 1961, the "bridge" remained intact from February 15 until at least March 21, despite several windstorms.

Flora

Isle Royale is in the Canadian biotic province (Dice 1943:Map I), just south of the arbitrary boundary of the Hudsonian province. Thus, it is actually in the transition zone between the two, and characteristics of both are evident.

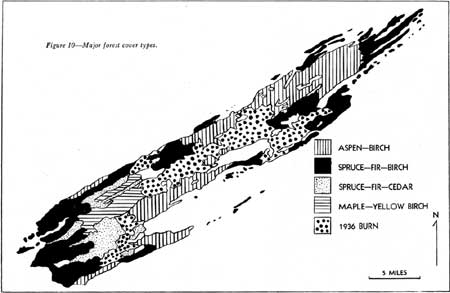

In the cooler, damper regions close to the lake, and in the narrow northeast section of the island, balsam fir (Abies balsamea) and white spruce (Picea glauca) comprise the climax forest; white birch (Betula papyrifera) forms small pockets in this type. According to Krefting (1951) the spruce-fir forest composes 29 percent of the island's cover. This climax is characteristic of the Hudsonian biotic province.

Typical of the Canadian province is the climax consisting of sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and yellow birch (Betula lutea), which predominates on the warmer, more mesic sites in the southwest third of the park. About 10 percent of the island's forest consists of this type (Krefting, 1951). Small local stands of northern red oak (Quercus rubra), white pine (Pinus strobus), red pine (P. resinosa), or jack pine (P. banksiana) occupy the most xeric ridges.

Swamps and lowlands support black spruce (Picea mariana), white cedar (Thuja occidentalis), and balsam fir.

About 56 percent of the forest cover is subclimax aspen (Populus tremuloides) and white birch, interspersed with conifer reproduction (Krefting, 1951). This type results from fires, and since most of Isle Royale has been burned over (Brown, n.d.), these subclimax stands are widespread. According to Hickie (n.d.), extensive fires occurred between 1870 and 1900. In 1936, fire swept approximately one-fourth of the island (Aldous and Krefting, 1946), and this area now supports predominantly white birch and some aspen. Willow (Salix spp.), fire cherry (Prunus pennsylvania), and choke-cherry (P. virginiana) also are scattered throughout the burn (figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7—Lush, second-growth hardwoods in the

1936 burn.

Figure 8—The 1936 burn in winter.

Figure 9—Heavily browsed birch and

aspen.

Figure 10—Major forest cover types.

Figure 10 shows the location and extent of the major cover types.

Shrubs and lesser trees are represented primarily by speckled alder (Alnus incana) along streams and in old beaver meadows; mountain alder (A. crispa) around lakes, bays, and rock openings; beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) in rock openings and old burns; mountain maple (Acer spicatum) in mixed woods and on rocky cliffs; mountain ash (Pyrus americana) on islands and in rock openings; black ash (Fraxinus nigra) in damp upland areas; serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) and wood rose (Rosa acicularis) on open ridges; red osier (Cornus stolonifera) along shores, bogs, and swamps; red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) in forest clearings, rock openings, and old beaver meadows; hush honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera) and thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus) in rock openings, mixed woods, and old burns. The latter probably is the most abundant and widespread shrub on Isle Royale.

Figure 11—American yew, a favorite moose

food, on Passage Island, one of the islands surrounding isle Royale.

Since there are no moose on this island, yew grow profusely, but on

Isle Royale this species is now very scarce.

Figure 12—Lush stand of young aspen making a return in the

Washington Harbor area.

Figure 13—Moose browse in winter.

One of the most common herbs is large-leaved aster (Aster macrophyllus), which grows in old burns, mixed woods, and rock openings in all parts of the park. Cow parsnip (Heracleum maximum) is widespread, in clearings and lightly shaded areas. Bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), twinfiower (Linnaea borealis), yellow clintonia (Clintonia borealis), and wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis) are also conspicuous in the understory. Open ridges support wood lily (Lilium philadelphicum), fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium), columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), bluebell (Campanula rotundifolia), self-heal (Prunella vulgaris), pearly everlasting (Anaphalis margaritacea), strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), goldenrod (Solidago spp.), and others.

Skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), marsh marigold (Caltha palustris), sedges (Carex spp.), and rushes (Juncus spp.) are typical herbs of Isle Royale swamps. The common aquatics are Nuphar, Nymphaea, Brasenia, Potamogeton, and Utricularia.

The most abundant and wide spread fern appears to be bracken (Pteridium aquilinum), which grows in old burns, along trails, on ridges, and in birch-aspen stands. Interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana) and several species of Dryopteris occupy the more shaded sites, and polypody (Polypodium virginianum) is widely distributed in shaded rocky areas.

C. A. Brown (n.d.) listed 671 ferns and flowering plants present on Isle Royale.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/7/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016