|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 7 The Wolves of Isle Royale |

|

HISTORY OF ISLE ROYALE MAMMALS

SINCE the study area is isolated, relatively few mammalian species are present. Furthermore, when a species disappears, it may not return for decades, if at all. Thus, significant shifts in species composition have been noted since Adams (1909) published the first list of mammals for Isle Royale. Man's role in these events is not fully known. However, he probably is responsible for exterminating the lynx and marten. The caribou and coyote apparently disappeared for other reasons. No attempt was made during the present study to complete a mammal survey, but incidental observations of mammals were made, and long-time summer residents of the island were interviewed regarding the past status of various species. (One cooperator first camped on Isle Royale in 1902!) Table 3 summarizes the information on shifts in the Isle Royale mammal community.

TABLE 3.—HISTORY OF ISLE ROYALE MAMMALS

[X=present; O=not observed]

| Species | Present in 1905 | Interim | Present status |

| Woodland caribou Rangifer caribou |

X | To about 1925. | O |

| Canada lynx Lynx canadensis |

X | To early 1930's. | O |

| Marten Martes americana |

X | O | O |

| Coyote Canis latrans |

O | X | O |

| Beaver Caster canadensis |

O | X | Common |

| Moose Alces alces |

? | X | Common |

| Red fox Vulpes fulva |

O | From about 1925. | X |

| Timber wolf Canis lupus |

O | From about 1948. | X |

| Snowshoe hare Lepus americanus |

X | X | Common |

| Red squirrel Tamiasciurus hudsonicus |

X | X | Abundant |

| Mink Mustela vison |

X | X | X |

| Long-tailed weasel Mustela frenata |

X | ? | X (Mustela sp.) |

| Short-tailed weasel Mustela erminea |

X | ? | X (Mustela sp.) |

| Muskrat Ondatra zibethica |

X | X | Scarce |

| Deer mouse Peromyscus manicutatus |

X | X | Common |

| Red-backed vole Clethrionomys gapperi |

X | O | Oa |

| Little brown bat Myotis lucifugus |

X | Xb | X |

| Keen's myotis Myotis keenii |

X | Xb | Xc |

| Big brown bat Eptesicus fuscus |

X | Xb | O |

| Silver-haired bat Lasionycteris noctivagans |

O | Xb | O |

| Hoary bat Lasiurus cinereus |

O | Xb | O |

| White-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus |

(12 introduced in 1906 eventually disappeared; Cole, 1956.) | ||

| Otter Lutra canadensis |

O | O | Od |

a A fragment of skull believed to be from Clethrionomys was found in a fox scat.

b Listed by Burt (1957) for Isle Royale.

c Reported by Johnsson and Shelton (1960).

d See page 20.

The lynx must have been plentiful on Isle Royale, for Adams (1909:413) reported: "Victor Anderson and son, John, secured 48 skins during the winter of 1903 and 1904. Most of these were from about three miles southeast [sic] of the head of Rock Harbor, in the vicinity of Lake Richie." Tracks or specimens were reported from most sections of the island.

Milford Johnson of Amygdaloid Island relates that lynx were being trapped by Bill Lively of the Michigan Conservation Department about 1925. Glen Merritt (Tobin Harbor) believes the species was present until about 1930, and Zerbey (1960:4) wrote that "In the early 1930's the Michigan Conservation Office trapped over 25 lynx." This is the last record of the species on Isle Royale.

Martens undoubtedly were common on the island at one time; Adams (1909:414) wrote: "During the past season [1905] Chas. Preulx took eleven Martens along the Desor trail . . ." Apparently, soon after this, the valuable and easily trapped furbearer disappeared. None of the interviewed early residents remembered the animal, and no other reports or mentions of it were found.

Adams also recorded that residents observed 2 woodland caribou near Blake's Point in the winter of 1904, and 9 on the ice near the Rock Harbor lighthouse in 1905; an ice fisherman about 5 miles out from Pigeon Point, Minn., spied 11 caribou on the ice toward Isle Royale. Julian G. Cross, whose father lived for many years at Silver Islet (near the tip of Sibley Peninsula, Ontario), wrote (personal correspondence, 1961) concerning the movement of caribou: "Previous to 1900, when caribou were abundant, they were often observed on the ice outside of Silver Islet singly, or in small herds. . . . These animals often could be observed traveling back and forth, apparently to Isle Royale, or following the shoreline in both directions."

Figure 14—Red squirrel. |

Pete and Laura Edisen observed a band of 14 to 16 on the ice near the Daisy Farm in 1922. Pete also noticed a single animal a few summers later in Conglomerate Bay. Milford and Myrtle Johnson saw caribou as late as 1925. This appears to be the last definite observation of the species on Isle Royale. Cole (1956:53), without giving details, reported that "small numbers of caribou or single animals were seen in 1904, 1915, 1920, 1921, and 1926." It is not known whether the caribou population was resident on Isle Royale or whether small bands merely migrated there from the mainland in winter.

The reason for the caribou's disappearance has not been ascertained. However, the history of the species on Isle Royale correlates well with that on the mainland. Before 1900 the caribou was common in northeastern Minnesota (Swanson et al., 1945) and in Ontario (de Vos and Peterson, 1951; Peterson, 1955), but it began to decline in numbers about the turn of the century (Hickie, n.d.). At present, it is rare along the north shore of Lake Superior. Perhaps the forest fires and invasion by man which occurred in the early 1900's altered the environment too drastically. If the Isle Royale herd was migratory, it also might have succumbed to these factors.

The most abundant mammal on Isle Royale in 1905 (possibly except for the deer mouse) was the snowshoe hare, according to Adams (1909). Commercial fisherman Sam Rude reported that hares were also plentiful in 1911 and 1922, but that since he settled in the southwest section of the island in 1927 he has seen none. Pete Edisen at the northeast end stated that in 1916, when he arrived, hares were abundant and remained so until the 1930's, but since 1936 he has seen very few. Murie (1934) reported hares very scarce in 1930. According to residents of Mott Island, the hare population there was high about 1950, but it decreased markedly by 1955. Cole (1956:53) observed that "the population level in the winter of 1955—56 was considerably below that of the winter of 1952—53."

The earliest record of the red fox on Isle Royale was furnished by Pete Edisen. He remembers seeing wild foxes outside the cages of black foxes raised by Bill Lively about 1925. Murie (1934), working in 1929 and 1930, also observed foxes. Later reports indicate that the population, although persisting, never was high.

Although Adams failed to mention the coyote, Glen Merritt of Tobin Harbor recalls that in 1902 "brush wolves" were plentiful. Mrs. William Lichte, also of Tobin Harbor, heard her grandfather, C. F. W. Dassler, speak of "wolves" on Isle Royale in the early 1900's, but her father, J. C. Dassler, informed her that these were coyotes. Pete Edisen said coyotes were present in 1916 when he arrived; Sam Rude remembers them in 1922; and Milford Johnson reported that they were common in 1925. Zerbey (1960) noted that coyotes were persecuted by residents from 1915 to 1935.

Murie (1934) found coyotes present in 1930, and Hickie (n.d.) stated that about 50 were taken in 1934—35. The occurrence of the species in 1945 was recorded by Aldous (1945), in 1946 by Gensch (1946b), and in 1949 by Krefting (1949b). Cole (1956:53) summarized more information:

Brush wolves trapped in the 1920's are believed to have been coyotes. A number were trapped in the winter of 1928—29 and from fifty to one hundred more the winter of 1934—35. During six months on Isle Royale, two observers saw 18 coyotes in the winter of 1941—42. They were reported plentiful in 1944 and scarce in 1945.

Cole, a National Park Service biologist, did much field work on Isle Royale from 1952 to 1957. During 3 weeks in the park in February 1957, he (1957:37) saw no coyotes and only one track, and concluded: "Apparently the Isle Royale coyote population has declined substantially the last five years." This is also the opinion of most island residents.

Beavers inhabited Isle Royale in the 1800's but apparently disappeared and then reappeared since. According to Adams (1909), the William Ives survey in 1848 indicated the presence of old beaver sign, and island residents in 1878 saw beaver dams and cuttings. Glen Merritt asserts that beavers were present in 1902. However, Adams obtained no recent evidence in 1905 and believed that trappers had exterminated the species. Pete Edisen saw no beavers from 1916 until the early 1920's, when they again were evident. In the southwest section of Isle Royale, Sam Rude noticed them first in 1927. Aerial photos taken in 1930 showed evidence of a small population (Gilbert, 1946).

According to Gilbert, beavers were trapped before the island became a National Park in 1940, and not until 1943 was an increase in the population noticed. "At that time the gradual spread of colonization could be easily discerned. Outlets to inland lakes began to show signs of beaver damming, a few isolated swamps showed beaver work, and dams began to appear in series along the streams." By 1945, beavers had colonized almost every stream, lake, swamp, and bay. Several worked-out colonies were found, and aspen had been depleted severely along many waterways; white birch was being resorted to.

Gensch (1946a) studied 57 beaver colonies and their food supplies in 1946, and Krefting (1963) studied 28 colonies in 1948. Many had been abandoned, and new ones had been established in almost every available location. The latter authors concluded that the food reserve in the center section and especially the southwest section was low; the northeast section had the best reserve. In 1951, Krefting again reported a dwindling aspen supply. Pete Edisen (Rock Harbor) and Sam Rude (Siskiwit Bay) noticed a decline in beaver numbers about 1950, and Cole (1954) found a significant decrease in the population in the Siskiwit Bay region from 1952 to 1954. All island residents interviewed agreed that the beaver population decreased sharply in the 1950's.

Although there is no definite record of the presence of otters on Isle Royale, it seems odd that such an aquatic mammal would not have found its way to the island. Indeed, certain circumstantial evidence was obtained during the present study indicating that otters are present. Milford Johnson reported that in the autumn of 1959 he found several 3- to-4-pound whitefish bitten into while in nets in the mouth of McCargo Cove and around Round Island. This damage sounded like something for which only an otter could be responsible. On August 23, 1960, I found mustelid-like tracks 2 inches long by 2-3/8 inches wide along the outlet of Hatchet Lake, and suspected they were otter tracks. Again, on June 14, 1961, I noted similar tracks on the beach at the head of Conglomerate Bay. These, too, looked like otter tracks I have seen on the mainland. A final piece of evidence came from Lt. Comdr. C. G. Porter, skipper of the U.S. Coast Guard's Woodrush, who observed what he believed to be an otter in Washington Harbor on June 17, 1960, for 10 minutes at a distance of 75 feet. Porter is familiar with both beavers and mink and was certain the animal was neither of these. Nevertheless, it remains for future studies to gather in disputable evidence.

Moose Irruption

Authors writing about the history of moose and caribou in the Lake Superior area (Hickie, n.d.; Swanson et al., 1945; de Vos and Peterson, 1951; Peterson, 1955) agreed that as the caribou population decreased from 1890 to 1910, moose, which had been scarce, became more common. By 1912 moose were "very common" in Lake County, Minn. (Johnson, 1922). Fires and logging probably benefited the moose at the caribou's expense.

Adams (1909) did not list moose as present on Isle Royale in 1905. He did mention an observation of some maples which had been broken down and stripped of leaves and bark and whose small branches had been eaten. He attributed this to caribou, but Murie (1934:10) wrote that it was probably ". . . the work of moose, for this type of feeding agrees exactly with the feeding habits of the moose and is not characteristic of the caribou." Hickie (n.d.) also believed that moose reached Isle Royale about 1905.

The popular theory is that the animals immigrated during the winter of 1912—13 when ice bridged the island with Canada. However, in 1915 the population size was estimated at 200 (Hickie, n.d.). Since moose are not herding animals, whenever they did reach the island, they probably did so in groups of one, two, or three. It seems unreasonable that there arrived enough separate groups to increase to any number near 200 in 2 years. Moreover, moose hesitate to cross even small stretches of ice, for it is difficult for them to maintain their footing there. Since moose are excellent swimmers and have been seen swimming in Lake Superior several miles from shore (Hickie, n.d.), it appears more likely that they reached Isle Royale by swimming from Canada. Indeed, P. M. Baudino of Calumet, Mich., told me that in the early 1930's in late June he observed a bull moose about half-way between Amygdaloid Island (part of Isle Royale) and Sibley Peninsula, swimming toward Canada.

Figure 15—Cow and calf swimming between islands in mid-July.

If the first moose which arrived on Isle Royale swam from Canada, they probably arrived in the early 1900's when the moose population increased substantially along the north shore of Lake Superior. By 1915, moose were well established on the island. Conditions apparently were ideal, for the herd increased to an extremely high density, as is shown in table 4. Most of the estimates presented are subjective and show only trends, but it is interesting that the figures (until 1930 when the peak was reached) fit the theoretical sigmoid curve expected when any species invades new favorable habitat.

TABLE 4.—ESTIMATES OF ISLE ROYALE MOOSE

| Year | Estimate | Source |

| 1915 | 200 | vide Hickie, 1936 |

| 1915-16 | 250-300 | vide Hickie, undated: 10a |

| 1917-18 | 300 | vide Hickie, undated: 10a |

| 1919-20 | 300 | vide Hickie, undated: 10a |

| 1921-22 | 1,000 | vide Hickie, undated: 10a |

| 1925-26 | 2,000 | vide Hickie, undated: 10a |

| 1928 | 1,000-5,000 | vide Hickie, 1936 |

| 1930 | 1,000-3,000 | Murie, 1934 |

| 1936 | 400-500 | Hickie, 1936 |

| 1943 | b171 | vide Cole, 1957: 8 |

| 1945 | b510 | Aldous and Krefting, 1946 |

| 1947 | b600 | Krefting, 1951 |

| 1948 | 800 | Krefting, 1951 |

| 1950 | 500 | Krefting, 1951 |

| 1957 | c300 | Cole, 1957 |

aBased on biennial reports of Michigan Game, Fish, and Forest Fire Department and from Department of Conservation. bDerived from aerial sampling. cAttempt at complete aerial census. | ||

Adolph Murie spent the summer of 1929 and spring of 1930 studying moose on Isle Royale. He (1934) found that all the winter browse species and several of the summer foods were overbrowsed and predicted that disease and starvation soon would cause an extensive die-off. According to Hickie (1936) this began in 1933. In the spring of 1934, approximately 40 dead moose were found on about 10 percent of the island; the few carcasses autopsied were emaciated. Hickie spent the winter of 1934—35 investigating the situation, and established that the browse was all but gone. Don R. Coburn, game pathologist, examined 24 carcasses, finding "little but malnutrition as the cause of death." In 1936, the population was estimated to be down to 400—500 animals. From 1934 to 1937, the Michigan Conservation Department live-trapped 71 moose and released them on the Michigan mainland. The starving animals were easy to lure into the traps (Hickie, n.d.).

Besides the harm to several species caused by overbrowsing, great damage to the balsam had been inflicted by the spruce budworm since 1929. In 1936 fire destroyed browse on more than a quarter of the island. Aldous and Krefting (1946) believed that the lowest moose population existed between 1935 and 1937.

A few years after the fire, browse was recovering in the burn, and the moose herd began increasing. In 1945 Aldous took an aerial sampling of the population and estimated that 510 moose were present (Aldous and Krefting, 1946). During the same study, an intensive browse survey led the authors to believe that Isle Royale's carrying capacity for moose had been reached.

Another aerial sampling, in 1947, produced an estimate of 600 moose (Krefting, 1951). A browse study in 1948 showed that browse was deteriorating, and another die-off was predicted (Krefting, 1951). Krefting believes that this occurred from 1948 to 1950. Several carcasses were found during these winters. The herd is estimated to have decreased from about 800 in 1948 to 500 in 1950 (Krefting, 1951).

During a month of browse investigation in the park during early 1953, Cole (1953) judged the moose food supply to be adequate. In 1956, he found that some of the browse was escaping, and he, too, believed that a marked moose reduction had started about 1949 (Cole, 1956). In early 1957, Cole attempted a complete aerial count of the moose. He observed 242 animals and estimated from tracks the presence of another 48 (Cole, 1957). (During the present study, this census technique was found to have serious limitations.)

Figure 16 —Washington Harbor. Winter

headquarters for personnel involved in wolf study is located at head of

harbor.

Advent of the Timber Wolf

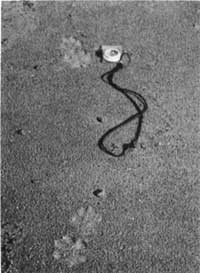

Figure 17—Wolf scats. |

The earliest claim we have of the presence of timber wolves on Isle Royale is from J. A. Lawrence. In correspondence of April 20, 1960, to D. L. Allen, Lawrence asserted that, from 1910 to 1920, timber wolves were hunted and trapped on the island and finally were exterminated. However, interviews with other residents of the same area and period indicate that the only wolves present at that time were brush wolves (coyotes).

Milford Johnson spent three winters (1924, 1925, 1931) on Isle Royale and believes he saw tracks of a single timber wolf each winter. During the 1930's or early 1940's Pete Edisen, who also overwintered three times on the island, reported that he saw wolf tracks during each. Ex-superintendent Charles E. Shevlin (1951) wrote:

Several years ago, two rangers on patrol observed what they believed to be a wolf, although, since neither was intimately familiar with the species, they could not be absolutely sure. They are, however, definite in their opinion that the animal was not a coyote. Other reports have been received from local fishermen to the same effect.

Milford Johnson reported hearing J. Cross, who lived all winter on Silver Island at the tip of the Sibley Peninsula, relate (about 1945) that he often watched wolves travel across to Isle Royale on the ice and could almost predict on what day they would return to the peninsula. However, Cross' son, Julian G. Cross, wrote (personal correspondence, 1961) that most of these wolves were of the "smaller or coyote variety." De Vos (1950:171) reported: "Mr. J. Cross saw a wolf pack from the air, several years ago, approximately south of Sibley, halfway between the peninsula and Isle Royale." Both Cross and de Vos noted that wolves crossed to Pie Island and Edward Island, and frequented Black Bay, Thunder Bay, and various other nearby bays and islands.

Figure 18—Wolf tracks in sand. |

If a wolf population had been established on Isle Royale during the 1930's or 1940's, it seems there would have been more positive evidence. None of the reports of studies conducted during this period mentions the possibility of timber wolves being present. In contrast, once wolves did become established, their tracks, scats, and howling became evident to anyone spending any period on the island. Thus, it appears that if there were wolves on Isle Royale between 1900 and 1945, they probably were single or visiting individuals.

During the late 1940's several reports of timber wolf sign culminated in the definite establishment of the presence of wolves on Isle Royale. Sam Rude relates that in the summer of 1948 he saw tracks much too big for coyote tracks, on a beaver dam on Little Siskiwit River. Cole (1952a) quoted from a report of N. W. Hosley concerning his trip to the island in September, 1949:

On the trails in the eastern part of the island droppings were found which were estimated to be 1-1/4 to 1-1/2 inches in diameter. Probably half of these contained moose hair. They were so large that the question was raised as to whether timber wolves had not reached the island.

Krefting (1949b) also reported discovering scats "unusually large for a coyote" in September 1949.

In November 1950, Hakala (1954) found tracks measuring 3-3/4 by 4-1/4 inches. These are within the usual range of wolf-track dimensions. (The largest measurement of coyote tracks given by Murie [1954] are 2-3/4 by 2-3/8 inches.) In May 1952, Cole (1952a) found wolf tracks and scats abundant.

Meanwhile, before the wolf was known to be present, a plan had gained impetus to establish a sanctuary for it. Murie (1934), Hickie (n.d.), Cahalane (vide Aldous and Krefting, 1946:308), Krefting (1951), and Neff (1951) had suggested introducing wolves on Isle Royale.

The original plan was to pay Michigan bounty hunters to secure two pairs of wolf pups, each pair from a different den. These pups were then to be released on Isle Royale with a wild-trapped adult female. However, the bounty hunters were unable to obtain wolves, so arrangements were made for the Detroit zoo to supply the animals. On August 9, 1952, four zoo-bred wolves were imported to Isle Royale. Since the creatures were not in the habit of fending for themselves, the plan was to keep and feed them in pens and allow them to come and go as they please, in hopes they would leave of their own accord and eventually revert to the wild.

Pens were built near the camp of Pete Edisen, Rock Harbor fisherman, who agreed to feed and care for the wolves while they were in his vicinity. This turned out to be a bit more of a chore than Pete had expected, for the wolves soon escaped their pens and began harassing the Edisens. The creatures tore up one of Pete's nylon fish nets and made off with several handmade rugs that his wife Laura had laid out to air. They began seeking food at various areas of civilization on the northeast end of the island, including Rock Harbor Lodge, the main tourist center of the park. Since the wolves were used to being fed by people, they fearlessly visited local residents and campers, scaring the wits out of most of them. One wolf approached a professor, who was out for a leisurely stroll with nothing but a camera to defend himself, and came so close that the prof ended up in a tree, swinging his camera at the persistent animal. He never did get a picture!

Figure 19—Resort area in Rock Harbor.

No one got eaten up, but many people were certain they had narrowly escaped such a fate. Thus Park Service personnel trapped the wolves and ferried them 30 miles away, but the next day the animals were back harassing tourists. Finally two of them were shot, one was trapped and returned to the mainland, and the fourth escaped. This individual, "Big Jim," had been reared at home by Lee Smits of Detroit and was an excellent retriever. He weighed 90 pounds when 8 months old and was about 15 months old when released. He never returned to the tourist lodge, but a year later, fishermen several times spotted a wolf swimming between islands and supposed it to be Big Jim, the retrieving wolf.

Figure 20—Cabin in Rock Harbor, where author and family spent summer of 1960 and 1961. |

Because of the wide publicity afforded the wolf-importation plan, many people still hold the misconception that the present Isle Royale wolf population is descended from the zoo-bred wolves. But, as has been stated, wild wolves were known to exist on the island before the tame animals were imported. Since the tame females were disposed of, the present Isle Royale wolf population must be free of any influence from the zoo wolves—with the possible exception of whatever stud service Big Jim may have performed.

On October 2, 1952, Hakala (1954) sighted one large and one small wolf on the Feldtmann Trail. Between February 17 and March 16, 1953, Hakala and Cole observed a pack of 4 wolves on Siskiwit Bay. They believed these to be an adult male, an adult female, and two pups (Hakala, 1953). (However, Stenlund [1955] and Fuller and Novakowski [1955] cautioned that winter size and weight of adults and pups overlap so much that age cannot be distinguished on such a basis.) Hakala and Cole also saw lone-wolf tracks which seemed too small to have been made by Big Jim. Thus, there were at least five wild wolves on Isle Royale in early 1953.

From February 9 to March 8, 1956, Cole (1956) found evidence of a pack of seven wolves (observed north east of Siskiwit Lake by his pilot), a group of two, a lone wolf, and at least one pack of four. He believes that there were two packs of four and another group estimated to contain four, all inhabiting the southwest end of the island. However, these estimates are based on tracks seen from the ground. The present study shows that wolves travel widely, and that even aerial observations of the animals themselves must be interpreted cautiously. Since Cole's estimated three packs operated in the same general area and each contained the same number of animals, the observed tracks probably could have been made by one pack of four. Nevertheless, it was quite definitely established that during early 1956 there were at least 14 wolves on Isle Royale (Cole, 1956).

From February 12 to March 2, 1957, Cole made an aerial survey of wolves and moose in the park. He observed a pack of seven wolves, a lone wolf, a pack of three, and tracks of a group of four. Although he believed that approximately 25 wolves existed on Isle Royale, he was certain only of the presence of 15 (Cole, 1957).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/7/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016