|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Research Report GRTE-N-1 The Elk of Grand Teton and Southern Yellowstone National Parks |

|

ELK HABITS

Information on elk habits was obtained while covering established routes through the study area. Routes were covered under a system which employed periodic aerial flights, horseback and foot travel through roadless areas, and vehicle trips. Observations of elk numbers, activities, occurrences on different habitat types, and locations were recorded. Most observations were made during early morning or evening when the animals were more observable and feeding. Animal locations were determined from gridded topographic maps. Sex and age classifications and identifications of individually marked animals were made whenever possible. Binoculars and a variable 15 to 60 power spotting scope were used.

Movements

Spring Migrations

During January through March periods when they were being fed hay, large groups of 1,000 to 4,000 elk concentrated on two or three feed ground sites within the south half of the National Elk Refuge. As snow-free areas became available and new grass growth started during April and May, the animals dispersed from feed grounds and ranged into the north half of the refuge. Snowstorms or inclement weather halted or even reversed these spring dispersals.

First migrations of significant numbers of elk (500 or more counted) off the refuge and onto Grand Teton lands occurred on April 30 in 1963, May 14 in 1964 and 1965, May 2 in 1966, and May 9 in 1967. Numbers moving onto Grand Teton Park progressively increased once migrations started. Movements to limited snow-free areas in the northern portion of the valley occurred over extensive flats with up to 1 foot of snow and over much deeper drifts. Such movements took the animals from refuge areas where new vegetation growth was abundant into areas where new growth either had not started or was so short as to be unavailable. The rate of spring movements by elk which migrated through Grand Teton into southern Yellowstone and the use of particular areas by females for calving appeared to be strongly influenced by snow accumulations in mountain passes. Proportionately fewer females with calves appeared to be present in southern Yellowstone during late June in 1962 and 1965 when June 1 snow depths at a representative 8,000 foot mountain pass exceeded 60 inches (Table 10). The proportion doubled in 1963 and 1966 when June 1 snow depths were 28 and 20 inches respectively. The highest proportion in 1964, with a 43-inch snow depth, appeared to represent a situation where intermediate mountain areas had sufficient snow accumulations to hasten, but not prevent, movements to lower elevations in Yellowstone Park. Yorgason (1964) reported from aerial flight observations that large numbers of elk migrated into Yellowstone Park over at least 10 councontinuouses of snow cover between May 9 and June 13. Alternative, more snow-free, but less direct, routes up main drainage courses were available. These apparently did not serve as alternative migratory routes for the majority of the animals that habitually traveled through mountain areas.

| Period | Total elk observed |

Classified | Percentages |

Calves/100 other adults |

June 1 snow depths | ||

| Adult males |

Other adults |

Calves | |||||

| June 24, 28, 1962 | 268 | 241 | 30 | 63 | 7 | 10 | 61 |

| June 24-27, 1963 | 571 | 449 | 25 | 62 | 13 | 20 | 28 |

| June 26, 1964 | 673 | 476 | 14 | 65 | 21 | 32 | 43 |

| June 29, 1965 | 408 | 380 | 34 | 60 | 6 | 10 | 70 |

| June 27-July 1, 1966 | 872 | 781 | 15 | 71 | 14 | 20 | 20 |

Elevational Movements

Recorded locations from 16,103 elk observations showed that progressively greater numbers of animals moved from low to high elevation ranges above 8,500 feet in southern Yellowstone through June and July (Table 11). Peak numbers were observed on high ranges during the last half of July during 4 of the 5 years; during the first half of July in 1966. The animals used forest types at both high and low elevations to a greater extent during the first half of August and were generally less observable. Movements from high to low elevations and even greater use of forest cover occurred during the last half of August and September. Some animals moved back to high elevations during late September and October in years when fall storms were not too severe.

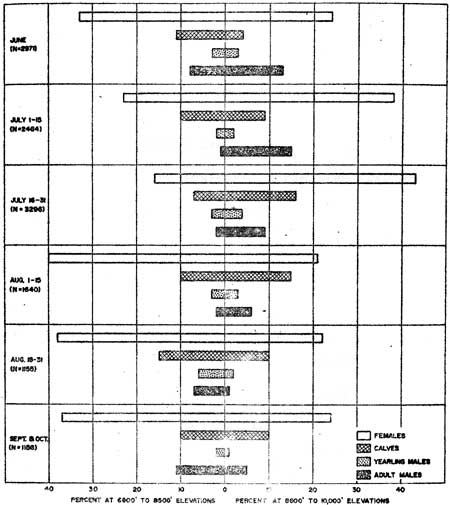

Sex and Age Differences

Classifications of 12,682 elk showed adult males and females not attending calves were most involved in initial June movements onto high elevation ranges above 8,500 feet (Figure 9). Females with calves or attached to female-calf groups was the population segment most involved in progressive movements to high ranges through July. Movements of adult males to high ranges appeared to be largely completed mid-July. Yearling males occurred in about equal proportions in early and late arriving groups. Adult males usually occurred in small groups apart from other population segments and at the highest elevations during late July. All sex and age classes were involved in early or mid-August dispersals into forest habitats and late August through September movements to lower elevations.

| Period | Total elk observed |

Elk above 8,500 feet | |

| Number | Percent | ||

| June 16-30 | 3,372 | 1,525 | 45 |

| July 1-15 | 3,126 | 1,824 | 58 |

| July 16-31 | 4,606 | 3,597 | 78 |

| August 1-15 | 2,521 | 1,800 | 71 |

| August 16-31 | 1,217 | 400 | 33 |

| September and October | 1,261 | 485 | 38 |

| 16,103 | 9,631 | ||

Insect Relationships

Midsummer aggregations of large numbers of elk at high elevations were influenced by molesting insects. Horseflies (Tabanidae) were obvious molesters of elk. Mosquitoes (Culicidae) caused avoidance reactions when very abundant. An unknown insect, possibly a heel fly (Oestridae), caused pronounced avoidance reactions in elk, but did not molest men or horses.

Numbers of elk observed on high elevation ranges during July and early August with different intensities of insect molesting activity are shown in Table 12. Intensities were considered high when elk almost solely occupied with avoiding or dislodging insects, moderate when such actions were secondary to other activities, and light when the animals appeared to be completely or almost unmolested. Peaks of molesting activity were through midday periods. High intensities caused obvious aggregations of elk on ridgetops and/or bedding in dense vegetation.

| Year | Relative abundance of molesting Insects |

Elk above 8,500 feet Number and average group size ( ) | ||

| July 1-15 | July 16-31 | August 1-5 | ||

| 1962 | Moderate late July, early August | 328 (27) | 650 (20) | 609 (24) |

| 1963 | Intense late July; moderate early August | 422 (23) | 1,036 (77) | 486 (20) |

| 1964 | Low all summer | 256 (21) | 671 (15) | 136 (8) |

| 1965 | Intense early August | 50 (27) | 990 (35) | 493 (19) |

| 1966 | Intense early July | 768 (18) | 250 (10) | 76 (7) |

Effects of molesting insects were most apparent in late July of 1963 and early July of 1966. This coincided with relatively high numbers of tabanids and the probable heel fly. The intense molesting action in early July caused the unusual occurrence of some females with young calves at elevations up to 10,000 feet. The habits of elk with the almost complete absence of insect molesting activity are reflected by the 1964 data. Elk remained scattered and in comparatively small groups throughout the summer. Similar scattered distributions occurred after early July of 1966.

Dispersals of elk into smaller groups usually occurred in early August. The effects of insect molesting activity occurring in or extending into August are illustrated by the 1962 and 1965 data. This suggests insects partially prevented elk dispersals into smaller groups. The relatively high elk numbers and group sizes seen during late July of 1965 appeared to result from the first migrations of large numbers of females with calves into Yellowstone National Park. These migratory groups dispersed and remained scattered in the absence of significant numbers of molesting insects through the remainder of the summer.

Intermingling Between Herds

The extent of intermingling between animals from the refuge and northern Yellowstone winter herds on the study area was indicated by 2,340 locations of marked elk (Table 13). Animals from these two almost 100-mile distant winter areas were shown to be intermingled to the greatest extent on Yellowstone summer ranges 50 to 55 miles from the south boundary of the refuge, to a lesser extent within 45 to 49 miles, and to a very limited extent on ranges south of Yellowstone Park. Simple proportion calculations, that related estimated herd sizes to numbers marked, suggested that at least 90 percent of the animals using the sampled central southern Yellowstone ranges were from the refuge winter herd during 1963 and 1964 (Cole, 1965). This figure may not be entirely applicable for the east and west portions of southern Yellowstone Park. A portion of the animals summering in the eastern Two Ocean Plateau and Thorofare regions were from the Gros Ventre winter herd and another herd which migrated east to winter ranges near Dubois, Wyoming (Murie, 1929; Anderson, 1958; Yorgason, 1964). A portion of the animals summering on the western Pitchstone Plateau region migrated southwest to Idaho winter ranges (Anderson, 1958) and possibly north to winter ranges along the Firehole and Madison Rivers inside Yellowstone Park.

| Month | Grand Teton valley |

North of valley |

Southern Yellowstone Park | |

| 7-25 miles | 26-44 miles | 45-49 miles | 50-55 miles | |

| April | 30 | |||

| May | 1,369 1 NY | 33 | ||

| June | 198 | 44 | 23 | 17 4 NY |

| July | 39 | 93 3 NY | 133 19 NY | |

| August | 45 1 NY | 50 6 NY | ||

| September | 11 | 19 | 7 1 NY | |

| October | 97 1 NY | 7 | 1 | |

| November | 45 | 43 | ||

| Refuge total | 1,739 | 177 | 181 | 207 |

| Northern Yellowstone total | 2 | 4 | 30 | |

In summary, the intermingling of elk from widely separated winter ranges, on and across mountain divide or plateau areas in southern Yellowstone Park, was a common occurrence. The presence of marked animals from two different winter ranges in a single group was also common during this study. Marked animals from three different winter ranges were occasionally seen together.

Despite this common intermingling on summer ranges, interchanges of animals between winter herds seemed to be less than would be expected. Over the 1962 through 1967 period, a maximum of three marked animals from the northern Yellowstone herd were present on refuge winter ranges during the winter of 1964-65. Numbers observed during other years ranged from none to two. Two marked refuge elk were observed on northern Yellowstone winter ranges in 1963-64; single animals, during each of the other 4 years.

Fall Migrations

The general pattern of fall and early winter migrations back to the National Elk Refuge is illustrated by the September through November locations of marked elk (Table 13). Other migration information was primarily from track counts on a 47-mile road transect and periodic counts of animals appearing on the refuge. The road transect started at park headquarters at Moose, extended through the west side of the park to Moran, and from here east to the top of Togwotee Pass (Figure 7). Elk track counts were started in 1945 by Cahalane (1949). They have been made cooperatively with Wyoming personnel since 1950, Park Service and Wyoming biologists alternate senior authorship in preparing annual migration reports. Interested persons are referred to these reports for detailed information on migrations.

Migration Chronology

Records over a 40-year (1927-1966) period date main migrations occurring 4 times in October, 24 times in November, and 2 times in December (Yorgason and Cole, 1967). Three of the four "main" October migrations occurred consecutively from 1960 to 1962. Combined numbers rating during November and December were actually greater than October. Track count records and aerial observations indicated most of the elk making early October migrations came from Grand Teton valley and mountain areas. Refuge counts indicate habitual October migrations by comparatively small numbers of elk started in 1958 (Table 14). Road closures within Grand Teton Park and specially designed hunting seasons aided in curtailing early migrations after 1964.

Tabulations of tracks crossing Grand Teton transects after snow fall and direct counts of elk within periods show the overall chronology of migrations for the majority of the animals summering in both national parks. Nine counts over the 10 years between 1957 and 1966 indicated that, on the average, about 5, 16, 28, 40, and 11 percent of these elk had migrated during October 1-15, October 16-31, November 1-15, November 16-30, and December 1-30 periods, respectively. These yearly track counts sampled the movements of an estimated 5,000 to 7,000 animals, depending upon the extent of early migrations before snow cover. Counts tallied between 40 and 80 percent of these animals. Low counts mainly resulted from snowstorms or mass movements obscuring tracks, or thaws that temporarily removed snow cover.

| 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | |

| Oct. 1-15 | 300 | 775 | 1,100 | 1,726 | 2,450 | 145 | 145 | 0 | 36 |

| Oct. 16-31 | 809 | 1,550 | 2,500 | 3,470 | 2,500 | 728 | 1,000 | 375 | 300 |

| Nov. 1-15 | 1,500 | 2,533 | 3,500 | 4,500 | 2,490 | 5,000 | 1,800 | 521 | 1,540 |

| Nov. 16-30 | 5,000 | 4,000 | 5,800 | --1 | 2,600 | 7,000 | 2,900 | 2,300 | 4,000 |

| Dec. 1-15 | 4,200 | 3,800 | 5,850 | 6,200 | --1 | 6,225 | 4,500 | 3,900 | --1 |

| Dec. 16-31 | 4,500 | 4,200 | 6,200 | --1 | 4,036 | --1 | 6,000 | --1 | --1 |

1 Elk scattered; count not possible.

Number Relationships

Accumulated track count records since 1949 show that the numbers proportions of elk crossing transect areas inside and outside Grand Teton have greatly changed over an 18-year period. Illustrative counts, at selected 6- and 7-year intervals, which sampled large numbers of elk are shown in Table 15. With the exception of the most eastern portion of the Four Mile Meadow to Togwotee Pass section (Figure 7), the transect mainly sampled animals migrating to the National Elk Refuge. The changes in numbers and proportions crossing different transect sections were generally progressive from about 1950 through 1958 and coincided with a period of relatively high hunting kills. Proportionately greater kills were apparently made on the more accessible migratory segments that crossed the eastern portions of Grand Teton (Buffalo and park boundary sections) and the transect sections outside park boundaries. Numbers decreased. Migratory segments that traveled through less accessible hunting areas (roadless or roads blocked by snow when migrations occurred) north of Grand Teton before crossing the Snake River and Pacific Creek transect sections were obviously less heavily hunted. These migratory segments increased. Increases in elk numbers crossing the Burnt Ridge section resulted from a buildup of a resident summer herd in Grand Teton after hunting eased on low security level valley habitats west of the Snake River.

In summary, the increases and decreases in particular migratory segments appeared to be in relation to their accessibility to hunters. Accessibility was largely determined by the presence of roads or the extent to which roads were blocked by snow during elk migrations.

| 1949 | 1957 | 1964 | |

| Park transects: | |||

| Burnt Ridge | 424 | 957 | 1,672 |

| Snake River | 1,285 | 1,091 | 2,122 |

| Pacific Creek Bridge | 700 | 1,025 | 1,416 |

| Buffalo River Bridge | 266 | 259 | 99 |

| Park Boundary | 842 | 626 | 371 |

| Park Total | 3,517 | 3,958 | 5,680 |

| Outside transects: | |||

| Blackrock | 3,492 | 1,159 | 395 |

| Four Mile Meadow | 3,146 | 1,112 | 1,028 |

| Togwotee Pass | 700 | 3,102 | 470 |

| Outside total | 7,338 | 5,373 | 1,893 |

| Grand total | 10,855 | 9,331 | 7,573 |

| Percent in park | 32 | 42 | 75 |

| Percent outside park | 68 | 58 | 25 |

Habitat Use

Patterns of elk habitat use within Grand Teton and refuge valley areas and mountain areas extending into southern Yellowstone Park were determined by recording the numbers of animals observed on the different vegetation types while covering routes. Multiple records were made when undisturbed animals moved from one type to another. Animals were about equally observable when they were using all but the forest types. Numbers observed in the forest types during the August through October period of greatest use were weighted by assigning the difference from maximum July counts to these types.

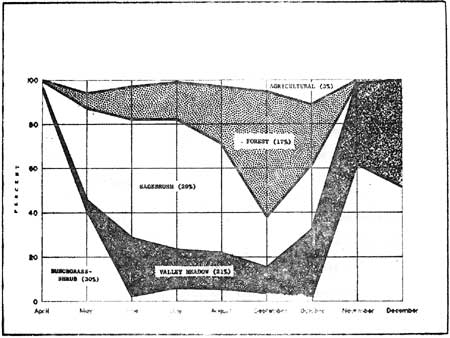

Valley Areas

General patterns of habitat use within valley areas were shown by 82,223 recorded elk observations between April and December (Figure 10). The sample included 42,237 May through October observations from 1963 and 1964 that were made by Martinka (1965). Additional observations were obtained within and on either side of this period from 1963 through 1966. The average sample size for monthly periods was 9,136 (5,525 to 19,398). April, November and December averages were from selected samples when large numbers of elk were freeranging off refuge feed grounds.

The recorded observations from late April illustrate the animals' maximum use of the bunchgrass-shrub type on upland slope sites after they dispersed from feed grounds and ranged over the northern portions of the refuge. Extensive areas of the type on an alluvial fan and hayfields were used to a greater extent when the animals first moved off feed grounds. May observations illustrate the animals' progressive shift to the sagebrush type as they migrated onto and used valley floor areas in Grand Teton Park. The bunchgrass-shrub type on south slopes remained important for its more advanced stages of vegetation growth. The predominant use of the sagebrush type for foraging is shown by the June through August observations.

Shifts to greater use of forest types occurred in August and increased during September. The October observations showed the animals increased their use of the valley meadow type and hayfields. This mainly occurred in October of 1962 and 1963 when large numbers of elk migrated to the refuge. Restrictions of human disturbances in Grand Teton areas closed to hunting and special hunting seasons reduced these movements in subsequent years and led to the greater use of the sagebrush type within the park.

November and December observations illustrate the animals' use of extensive bunchgrass-shrub and valley meadow types. Use at this time of year appeared to be almost exclusively on high producing bottomland sites or within swales on uplands. Variable additional use occurred on hayfields in some years. This appeared to depend upon whether fall rains caused regrowth or they had been left uncut. The start of artificial feeding in January caused the majority of the animals on the refuge to abruptly leave natural food sources and move onto feed grounds.

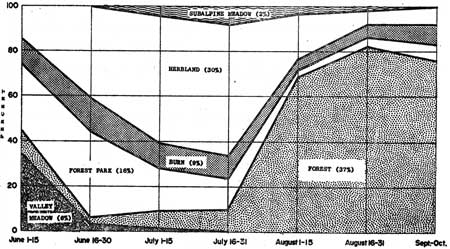

Mountain Areas

Patterns of use on different vegetation types in mountain areas were shown by 20,017 recorded elk observations between June and October of 1962 through 1966 (Figure 11). Sample sizes for periods ranged from 641 during the first half of June to 6,543 during the last half of July.

Figure 11 shows that the majority of the animals arriving in mountain areas in early June used the relatively low elevation valley meadow (willow-sedge stage) and forest park types. These were principally female-calf groups. Late June through July observations illustrate progressive shifts in elk use from the low elevation types to the intermediate elevation burn type and finally, the herbland type. Maximum use of the highest elevation subalpine meadow type usually occurred during late July. August through October observations illustrate the elks' dispersals into and predominant use of forest types.

In 1962, a late emergence of molesting insects appeared to hold substantial numbers of elk on the herbland and subalpine meadow types into the first half of August (Table 12). In late July and early August of 1964, molesting insects were scarce. Elk occurred in scattered small groups and used forest and low elevation forest park types to the greatest extent observed during the study. In 1965, snow accumulations along migratory routes appeared to preclude the usual use of lower elevation mountain areas for calving. Large female-calf groups moved directly onto Yellowstone's high elevation herbland types in late July. In 1966, an early July emergence of molesting insects caused concentrations on high elevation herblands comparable to late July and early August highs observed in other years. Subsequent late July and early August use of high elevation ranges was the lowest observed during the study.

Food Habits

Information on food habits was obtained by recording 262,602 instances of plant use at 473 elk feeding sites. The unit for recording one instance of use from April 16 through November 15 was a rooted stem for forbs and single-stemmed grasses, a leader for shrubs, or a distinct clump of stems for bunchgrasses. A unit recorded during this period could be considered roughly equivalent to a "bite."

During the November 16 through April 15 winter period, elk frequently grazed bunchgrasses closely. On sites where shrubs were also used the above system was modified. Recorded instances of use on bluebunch wheatgrass, or other grasses with a similar life form that were grazed to average heights of 1, 2, 3, or 4 inches, were multiplied by weight values of 25, 20, 15 or 10, respectively. Instances of use on needle-and-thread, or other comparable grasses that were grazed to 0.5, 1, or 2 inch average heights, were multiplied by weight values of 11, 8, or 5, respectively. These weight values made units of use on bunchgrass plants more equivalent in weight to units for shrubs and the few forbs used during this period.

The base weight values of 25 and 11 were obtained by dividing the average air dry weight of 100 2-inch shrub leaders (N = 400) into the air dry weight of 100 bluebunch wheatgrass plants clipped to 1 inch and 100 needle-and-thread plants clipped to 0.5 inch. Leader samples were from Douglas rabbitbrush and winterfat and weights were approximately equal. Weight values for other bunchgrass stubble heights were obtained from proportion calculations that utilized the "utilization gauge" developed by Lomason and Jenson (1938).

The only departure from the described method was that the side branches of tall larkspur and individual stems of giant wild rye plants were considered special units for recording one unit of use. Most feeding sites were examined while fresh use could be detected, but were allowed to accumulate use over known periods when elk were only animals involved. Examinations were purposely restricted to sites that had not been used to the extent that animal preference obscured.

Elk use was mainly on cured grass during the November 16 through April 15 winter season. New growth of grasses usually became increasingly availabile as a food source through the first half of spring; forbs, during the last half of the period (April 16 to May 16 or June 30). Variation occurred with late and early springs. Forbs were readily available on most habitat types through the summer (up to September 15), though some cured to the extent that they ceased to be used. The freezing or curing of forbs in fall (September 16 to November 15) resulted in elk shifting their use to other forage sources.

Plant terminology generally follows Davis (1952) and Booth and Wright (1959), except that grasslike sedge and rush species are included in the grass forage class. Grazed and vegetative forms of fleabane or aster plants could not be readily identified and are collectively called asters. Instances of elk use on plant species (or related groups) were calculated as percentages of the total recorded use at each feeding site. Percentages were averaged for the different vegetation types by seasonal periods. Results by forage classes are shown in Table 16. Plants that received 5 percent or more of the recorded use and/or were used at 25 percent or more of the sites are shown in Appendix Tables V through IX. An alphabetical listing of common and scientific plant names is given in Appendix I. Discussions of food habits by seasons follow.

Winter

Grasses were the predominant class of forage used by elk feeding on the upland bunchgrass-shrub and valley meadow types (Table 16). Bluebunch wheatgrass and Douglas rabbitbrush were the two most important plant species used on the upland type as a whole (Appendix V). Needle-and-thread or bluegrasses were additionally important food items within swales during the first half of winter and again on a variety of other upland sites as new growth started during late winter. Combined use on these four plant species averaged 79 percent of the recorded instances of use. Sedge, bluegrass, and willow were the most important species used on the valley meadow type (Appendix VI). Combined use averaged 76 percent.

Shrubs were the predominant class of forage used by elk feeding within forest types during winter. Willow, narrowleaf cottonwood, aspen, and silverberry in combination with bluegrasses were the most important items used in aspen or cottonwood stands (Appendix VII). Combined use was 70 percent. A variety of shrubs and sedge served as the main food source for animals feeding within coniferous forest stands (Appendix VII). Combined use was 72 percent.

| Seasons2 | Vegetation types | No. sites |

Instances of use |

Percent | ||

| Grass3 | Forbs | Shrubs | ||||

| Winter | Bunchgrass-Shrub | 51 | 163,837 | 72 | 2 | 26 |

| Valley-Meadow | 8 | 6,152 | 71 | 2 | 27 | |

| Forest (Deciduous) | 4 | 3,016 | 43 | 6 | 51 | |

| Forest (Coniferous) | 9 | 9,657 | 37 | 9 | 54 | |

| Spring | Bunchgrass-Shrub | 24 | 4,606 | 75 | 14 | 11 |

| Valley-Meadow | 19 | 7,836 | 60 | 36 | 4 | |

| Sagebrush | 43 | 8,257 | 54 | 44 | 2 | |

| Forest Park | 37 | 8,107 | 33 | 66 | 1 | |

| Burn | 5 | 1,422 | 57 | 42 | 1 | |

| Herbland | 5 | 1,102 | 48 | 52 | 0 | |

| Forest (Deciduous) | 16 | 4,127 | 50 | 49 | 1 | |

| Forest (Coniferous) | 18 | 3,053 | 40 | 39 | 21 | |

| Summer | Valley-Meadow | 9 | 1,484 | 23 | 7 | 70 |

| Sagebrush | 59 | 7.637 | 4 | 92 | 4 | |

| Forest Park | 33 | 5,369 | 14 | 82 | 4 | |

| Burn | 15 | 2,546 | 13 | 83 | 4 | |

| Herbland | 30 | 5,488 | 15 | 85 | 0 | |

| Subalpine Meadow | 14 | 3,351 | 50 | 50 | 0 | |

| Forest (Deciduous) | 17 | 3,256 | 25 | 50 | 25 | |

| Forest (Coniferous) | 26 | 3.960 | 10 | 47 | 43 | |

| Fall | Valley-Meadow | 3 | 2,632 | 93 | 5 | 2 |

| Sagebrush | 10 | 1,348 | 74 | 25 | 1 | |

| Forest Park | 6 | 1,265 | 56 | 29 | 15 | |

| Herbland | 3 | 165 | 45 | 55 | 0 | |

| Forest (Coniferous) | 9 |

2,929 | 52 | 8 | 40 | |

| 473 | 262,602 | |||||

1 Data for valley areas involving 5,361 instances of use included from 44 sites examined by Martinka (1965).

2 Winter, November 16-April 15; spring, April 16-June 15 in valley areas, May 16-June 30 in mountain areas; summer up to September 15; fall up to November 15.

3 May include grasslike sedge and juncus spp.

Spring

Grass continued to be the predominant class of forage used on most types over the spring season as a whole. Forb use about equaled or exceeded that on grass on half the types. The bunchgrass-shrub type was mainly used before forbs became readily available. Bluebunch wheatgrass and bluegrasses were the most important food items (Appendix V). Combined use averaged 58 percent.

Bluegrass and sedge species were the most important plants used on the valley meadow type (Appendix VI). Combined use was 55 percent. Bluegrass, Idaho fescue and balsamroot were the most important species used by elk moving onto or migrating over the outwash plain, sagebrush type during spring (Appendix VIII). Combined use on these species was 42 percent.

Sedge, mountain and nodding brome, geranium, dandelion and other forbs served as the main food items for elk feeding within the forest park type during spring (Appendix IX). Forb and grass use was 66 and 33 percent respectively. Mountain brome, sedge and geranium were the most important plants used on the burn type during spring (Appendix IX). Combined use was 58 percent. Mountain brome, slender wheatgrass, violet and agoseris were the most important items on the high elevation herbland type. Combined use averaged 65 percent.

Bluegrass and a variety of forbs served as the most important food for elk feeding in deciduous forest stands (Appendix VII). Sedge and pinegrass were the most important individual items in coniferous stands. Aggregate forb and grass use was about equal in both deciduous and coniferous stands, but shrubs continued to be used to a greater extent within the latter.

Summer

Forbs were the predominant class of forage used by elk on all but the valley meadow and the highest elevation subalpine meadow types. Willows were the most important food item on the former type, averaging 70 percent (Appendix VI). Sedge and aster species and lupine were the most important food items on the subalpine meadow type, aggregating 62 percent (Appendix IX).

Lupine was the most important single food item on the sagebrush type over the summer as a whole, averaging 50 percent (Appendix VIII). It was used to the greatest extent after other vegetation cured during late summer or was killed by frost. Agoseris, buckwheat, little sun flower, and balsamroot were more important during the early summer. Combined use on these and lupine was 79 percent.

Agoseris, potentilla, dandelion, and aster were the most important forb species used by elk feeding on the forest park, burn and herb land types during the summer (Appendix IX). Combined use averaged 55, 42, and 60 percent for each type, respectively. These were obviously highly preferred forage plants which were selectively used even on sites where they were a minor component of the vegetation. The species had widespread distribution. However, they were relatively abundant on sites that had been disturbed by pocket gophers (Thomomys talpoides) on immature soils, and on ridgetop sites that elk may have maintained in a disclimax stage.

Aster, dandelion, and agoseris were the most important forbs used in both deciduous and coniferous forest stands during the summer (Appendix VII). These three species, nodding brome, wheatgrasses, and aspen received 51 percent of the elk use in deciduous stands. They received 56 percent, in combination with lupine, spirea, and huckleberry, in coniferous stands.

Fall

Grass was the predominant class of forage used on most types during fall. Bluegrass was the most important single item on sampled valley meadow types, averaging 91 percent of the recorded use (Appendix VI). Junegrass, bluebunch wheatgrass, bluegrass, and lupine were the most important on the sagebrush type. Combined use was 70 percent (Appendix VIII). The increased use of grass on these types appeared to be in response to most forbs losing their succulence and fall rains causing new leaf growth on bluegrasses and junegrass.

Mountain brome and lupine appeared to be the main plants used by the relatively few elk that continued to forage on the herbland type during fall (Appendix IX). Combined use was 59 percent. Sedges and the aster-fleabane-goldenrod group of plants were most important food items within the forest park type. Combined use was 76 percent. Geyer's sedge, pachystima, spirea, and huckleberry were the most important plants used by elk feeding within coniferous forest stands (Appendix VII). Combined use averaged 79 percent.

Seasonal and Yearlong Averages

The two forest types used during winter were estimated to provide at least 10 percent of the November 15 through April 15 diet for free-ranging elk as a whole. Proportionately weighted grass, forb, and shrub averages for the two forest types and the nonforest types which provided the main source of winter food were 69, 2, and 29 percent, respectively.

Respective grass, forb and shrub averages were 50, 45, and 5 percent for the different habitat types used during spring; 19, 62, and 19 percent for summer. The unadjusted values would be expected to vary with late springs resulting in an increased use of grass and shrubs; early springs, an increased use of forbs. The unweighted summer values probably would not vary greatly during years when animals used certain habitat types to a greater extent than others. The general use of different habitat types through spring and summer was considered to preclude any meaningful weighting of averages.

Recorded observations of elk indicated that their relative use of forest and nonforest types may have been in a ratio of about 75 to 25 percent during the fall (Figure 11). By this relationship, fall use of grass, forbs, and shrubs averaged 56, 13, and 31 percent, respectively.

The winter, spring, summer, and fall forage class averages extended over about 5, 2, 3, and 2-month periods, respectively. Proportionate weighting of seasonal forage class figures gave an average yearlong food habit of about 51 percent grass, 26 percent forbs, and 23 percent shrubs for free-ranging elk. These values could be expected to vary with elk groups using particular vegetation types extensively, during years with extreme weather, or with animals that also used artificial food on feed grounds. What is perhaps best shown by the food habits study is that elk are extremely versatile and generalized feeders on all classes of forage and on a variety of plant species. Important winter food plants were major components in either seral stages or climax stands. This obviously enables the elk to contend with a broad spectrum of environmental change and persist as a faunal dominant in the Grand Teton and Yellowstone environments.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/8/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016