|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Mountain Goats in Olympic National Park: Biology and Management of an Introduced Species |

|

| The Olympic Peninsula |

CHAPTER 3:

Biogeography of the Olympic Peninsula

D. B. Houston, E. G. Schreiner, and N. M. Buckingham

Examination of the Olympic Peninsula's biogeography provides background necessary for understanding the mountain goat issue. The peninsula supports a unique assemblage of plants and animals; some points of interest are the evolution of endemic forms,3 the reduced mammalian species diversity compared to more mainland continental regions, and the presence of plant taxa with intriguing distributions. Features of the geographic setting and the landscape-level events that have strongly influenced evolution of the Olympic biota include

1. the mountainous peninsular landform, sculpted repeatedly by glaciers of different origins and coverages;

2. the temporally varying isolation of the area as a peninsula and the associated changes in land mass as sea level and ice cover fluctuated (the Puget Trough lacked a marine embayment and the coastline was farther west during glacial maxima);

3. the strategic location of the peninsula at the southwestern corner of the massive Cordilleran ice sheet during the Fraser glaciation;

4. isolation of subalpine and alpine areas for at least 10 millennia as habitat islands in the mountain range, surrounded by forest and water (Barnosky 1984);

5. sharp precipitation and elevation gradients that have yielded a broad array of habitats within a comparatively small area; and

6. the moderating influence that the Pacific Ocean has on climate.

3Endemics are organisms whose distributions are limited to one geographic area. We emphasize taxa that are endemic to the Olympic Peninsula or to the peninsula and Vancouver Island.

Endemic Organisms

Populations of plants and animals differing in appearance geographically and through time represent the substance of evolution. Assessing the degree of differentiation among populations is the substance of taxonomy and systematics. Differences between populations may be sufficient to warrant recognition of each as distinct biological species, the fundamental unit of evolution (Mayr 1963, 1970).4 Less pronounced variation among populations may be recognized by designating subspecies and varieties and, for still lesser variation, races, ecotypes (mainly plants; Harper 1981; Merrell 1981; Kruckeberg and Rabinowitz 1985), or stocks (fish; Ricker 1972). Most degrees of variation—endemic species, subspecies, varieties, races, and stocks—have been described for the biota of the Olympic Peninsula. We are concerned primarily with variation at the level of species, subspecies, and varieties but occasionally note other forms described in the scientific literature.

4In the Biological Sciences Concept, species are groups of interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups.

Assessing levels of taxonomic differentiation may be difficult. The validity and meaning of biological species, subspecies, and varieties are debated among scientists (e.g., Mayr 1982, 1992). Accepted definitions of these terms change periodically and may differ among scientific disciplines (Futuyma 1979; Merrell 1981; Kruckeberg and Rabinowitz 1985; Geist 1991; Mayr 1992). We recognize these complex scientific issues, as well as the likelihood that criteria used to differentiate taxa are themselves evolving, particularly as analytical techniques become more sophisticated (e.g., analysis of DNA patterns). Nevertheless, 35 endemic forms of plants and animals are currently recognized on the Olympic Peninsula (Table 1).

Table 1. Endemic fauna and flora of the Olympic Peninsula.

| Common name | Scientific name | Source |

| VERTEBRATES | ||

| Mammals | ||

| Olympic marmot | Marmota olympus | Hall 1981 |

| Olympic yellow-pine chipmunk | Tamias amoenus caurinusa | Hall 1981 |

| Olympic snow mole | Scapanus townsendii olympicus | Johnson and Yates 1980 |

| Olympic Mazama pocket gopher | Thomomys mazama melanops | Hall 1981 |

| Olympic ermine | Mustela erminea olympica | Hall 1981 |

Amphibians | ||

| Olympic torrent salamander | Rhyacotriton olympicus | Good and Wake 1992 |

Fish | ||

| Olympic mud minnow | Novumbra hubbsib | Wydoski and Whitney 1979 |

| "Beardslee" rainbow trout (lacustrine form) | Oncorhynchus mykiss irideusc | R. Behnked 1992 |

| "Crescenti" cutthroat trout (lacustrine form) | Oncorhynchus clarki clarkic | R. Behnked 1992 |

INVERTEBRATES | ||

Insects | ||

| Lepidoptera—butterflies and moths | ||

| Olympic arctice | Oeneis chryxus valerata | Burdick 1957 |

| Hulbirt's skipper | Hesperia comma hulbirti | Lindsey 1939 |

| Orthoptera—grasshoppers | ||

| Olympic grasshopper | Nisquallia olympica | Rehn 1952 |

| Coleoptera—beetles | ||

| Mann's gazelle beetle | Nebria danmanni | Kavanaugh 1981 |

| Quileute gazelle beetle | Nebria acuta quileute | Kavanaugh 1979 |

| Sylvan gazelle beetlee | Nebria meanyi sylvatica | Kavanaugh 1979 |

| Johnson's snail eatere | Scaphinotus johnsoni | Van Dyke 1924 |

| Tiger beetle | Cicindela bellissima frechini | Leffler 1979 |

Millipedes | ||

| Millipedee | Tubaphe levii | Causey 1954 |

Molluscs | ||

| Arionid slug | Hemphillia dromedarius | Branson 1972 |

| Arionid jumping slug | Hemphillia burringtoni | Pilsbry and Vanatta 1948 |

VASCULAR PLANTS | ||

| Pink sandverbenae | Abronia umbellata acutulata | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Olympic Mountain mitkvetch | Astragalus australis var. olympicus | Isely 1983 |

| Piper's bellflower | Campanula piperi | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Flett's fleabane | Erigeron flettii | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Thompson's wandering fleabane | Erigeron peregrinus peregrinus var. thompsoniif | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Henderson's rock spirea | Petrophytum hendersonii | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Webster's senecio | Senecio neowebsteri | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Olympic Mountain synthyris | Synthyris pinnatifida var. lanuginosa | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Flett's violet | Viola flettii | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Olympic astere | Aster paucicapitatus | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Magenta paintbrushe | Castilleja parviflora var. olympica | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Lance-leaf springbeautye | Claytonia lanceolata var. pacifica | McNeill 1972 |

| Blood-red pedicularise | Pedicularis bracteosa var. atrosanguinea | Kartesz and Kartesz 1980 |

| Tisch's saxifragee | Saxifraga tischii | Skelly 1988 |

CRYPTOGAMS | ||

| Liverworte | Porella roellii forma crispata | Hong 1987 |

aTrinomials indicate subspecies.

bOccurs south to Chehalis River. cFormerly considered a distinct species; currently considered a lake-adapted form of the subspecies. dR. Behnke, personal communication. eAlso occurs on Vancouver Island. fNot found in Olympic National Park. | ||

Fifty-eight species of mammals occurred historically on the Olympic Peninsula (excluding marine mammals but including the gray wolf [Canis lupus], which was extirpated by 1930 and the white-tailed deer [Odocoileus virginianus], which was apparently eliminated by 1900).5 Of these, five endemics are currently recognized, including one species and four subspecies. The three endemic rodents and the insectivore are associated with subalpine and alpine environments.

5Small numbers of white-tailed deer occurred historically in the Puget Lowlands; one specimen is known from the peninsula.

No endemic birds or reptiles are recognized, but one endemic amphibian, the Olympic torrent salamander (Rhyacotriton olympicus), has been recently described. Although the population of the Cope giant salamander (Dicamptodon copei) is centered on the peninsula, scattered, small populations also occur in southwest Washington and locally in Oregon streams that drain into the Columbia River Gorge (300 km distant). Consequently, the animal is not truly endemic (R. B. Bury, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Collins, Colorado, personal communication, 1992). The tailed frog (Ascaphus truei) in the Olympics may be sufficiently distinct to warrant recognition as a species, but additional genetics research is required (D. Good, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, personal communication, 1992).

Only one fish species is currently recognized as endemic—the Olympic mud minnow (Novumbra hubbsi). The resident cutthroat (Oncorhynchus clarki) and rainbow trout (O. mykiss) from Lake Crescent were described initially as species but are now considered lake-adapted forms of more widespread subspecies. Marked genetic differences separate stocks of anadromous salmon that spawn in the rivers of the peninsula (Reisenbichler and Phelps 1987), but these are not included in Table 1.

Endemism among Olympic invertebrates is difficult to assess because most groups are poorly known. We restrict consideration to several orders of insects and a few other groups whose taxonomy and distribution seem reasonably well understood. However, we regard even these interpretations as provisional. Currently, nine arthropods (eight insects, one millipede) and two mollusks are considered endemic to the peninsula or to the peninsula and Vancouver Island. The insects include five beetles (one species, four subspecies), two lepidopterans (subspecies), and one grasshopper (species). Five of the insects are associated with high montane or subalpine areas.

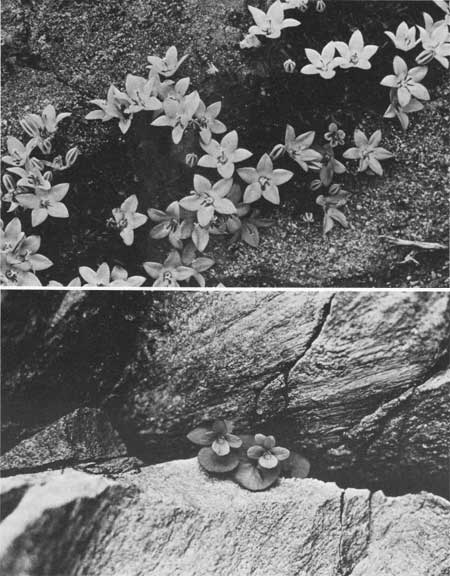

Fourteen vascular plant taxa are either endemic to the peninsula (eight; Fig. 11) or to the peninsula and Vancouver Island (six). Of these, Thompson's wandering fleabane (Erigeron peregrinus ssp. peregrinus var. thompsonii) occupies lowland swamps and bogs, and pink sandverbena (Abronia umbellata var. acutulata) was collected historically on the Olympic coast (now possibly extinct). All others (seven species, five subspecies or varieties) occur mainly in the alpine and subalpine zones.

|

| Fig. 11. The endemic Campanula piperi (bellfiower; upper) and Viola flettii (Flett's violet) occupy rock crevices in the subalpine and alpine zones of the Olympic Mountains. The bellflower is known to be eaten by mountain goats. (National Park Service photos) |

The taxonomy and distribution of nonvascular plants and fungi are poorly understood. We know of no cryptogams (mosses, lichens, liverworts) or fungi that are endemic to the peninsula; however, one liverwort form is limited to the Olympic Peninsula and to Vancouver Island (Hong 1987). Preliminary inventories of alpine sites suggest that cryptogam diversity is unusually high in the Pacific Northwest—it seems reasonable that endemic forms will be discovered eventually (J. A. Henderson, U.S. Forest Service, Mountlake Terrace, Washington, personal communication, 1992).

Species Diversity

Animals

The terrestrial mammal fauna (48 species, excluding bats and marine mammals) of the Olympic Peninsula is impoverished compared to the nearby Cascade Range in Washington. Early naturalists and mammalogists reported 12 species absent from the Olympic Peninsula, although suitable habitat seemed to be present (Table 2). Species noted as absent, at least during historic time, consist of five carnivores, four rodents, a lagomorph (pika [Ochotona princeps]), and two ungulates, including the mountain goat. The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and goat were introduced subsequently. The coyote (Canis latrans) reportedly colonized much of western Washington, including the Olympic Peninsula, during the early twentieth century—seemingly after gray wolf populations had been decimated (Dalquest 1948). Porcupines (Erethizon dorsatum) have been reported rarely during the past few decades; evidently a population has not become established.

Table 2. Mammal and bird species present in the Cascade Mountains but absent historically from the Olympic Peninsula.a

| Common name | Scientific name | Source |

| Mammals | ||

| Grizzly bear | Ursus arctos | D, J, M, Sb |

| Wolverine | Gulo gulo | M, S |

| Red foxc | Vulpes vulpes | M, S |

| Coyoted | Canis latrans | M |

| Lynx | Lynx canadensis | J, S |

| Water vole | Microtus richardsonii | M, S |

| Golden-mantled ground squirrel | Spermophilus lateralis | D, J, M, S |

| Northern bog lemming | Synaptomys borealis | D, S |

| Porcupinee | Erethizon dorsatum | M, S |

| Pikaf | Ochotona princeps | D, J, M, S |

| Mountain sheep | Ovis canadensis | D, M, S |

| Mountain goat | Oreamnos americanus | D, J, M, S |

| Birds | ||

| White-tailed ptarmigan | Lagopus leucurus | Sharpeg |

aScientific names from Honacki et al. (1982). bD = Dalquest 1948: J = Johnson and Johnson 1952; M = Merriam (no date, circa 1897, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, unpublished notes and manuscript): S = Scheffer, Mammals of the Olympic Peninsula. Olympic National Park library, unpublished manuscript, 1949. (Note: Merriam compared biota of Olympic Mountains to that of Mount Rainier. He also considered gray fox [Urocyon spp.] to be absent, but that species was absent from the entire state.) cSubsequently introduced (Aubry 1984). dColonized the Olympic Peninsula during the early twentieth century (Dalquest 1948). eOccasional dispersing individuals, apparently no established population (Johnson and Johnson 1952: NPS unpublished records; Scheffer, Mammals of the Olympic Peninsula, Olympic National Park library, unpublished manuscript, 1949). fMerriam found no pikas but was uncertain that they were entirely absent. gF. A. Sharpe, Western Washington University, Bellingham. personal communication, 1992. | ||

The avifauna of the Olympics also differs from that of the Cascades. The white-tailed ptarmigan (Lagopus leucurus) is absent, and seven other species common in the Cascades are currently known as either rare residents (spruce grouse [Dendragapus canadensis]) or as seasonal migrants and rare individuals without breeding populations, even though suitable nesting habitat seems to be present (dusky flycatcher [Empidonax oberholseri], mountain chickadee [Parus gambeli], mountain bluebird [Sialia currucoides], Nashville warbler [Vermivora ruficapilla], Cassin's finch [Carpodaciis cassinii], Lincoln's sparrow [Melospiza lincolnii]; F. A. Sharpe, Western Washington University, Bellingham, personal communication, 1992; R. A. Hoffman, Olympic National Park, personal communication, 1992). Most records of these rare migrants are from the dry northeastern corner of the Olympics where some habitats seem analogous to the east slope of the Cascades. Possibly the amount of such habitat is currently insufficient to sustain viable, breeding populations.

Plants

Comparing the vascular plant diversity of the Olympics (~1,200 native taxa) to other areas is confounded by taxonomic bias (i.e., lumpers vs. splitters) in the regional floras (e.g., Alaska—Hulten 1968; Washington, Oregon, and Idaho—Hitchcock and Cronquist 1973; Canada—Scoggan 1978). These biases limit our ability to make comparisons as we did with birds and mammals. Nonetheless, the Olympic flora is notable for the absence of species common in the Cascades, as well as the presence of species not found in the Cascades. We limited comparisons to plants at high elevations that were identified from a common taxonomic source and to the conifers—a taxonomically stable group that represents the dominant vegetation.

Subalpine and alpine vascular floras of the Olympics and the North Cascades differ, but neither is necessarily more diverse (Pike 1981). Twenty-four percent of 1,054 native Olympic species were not found in the North Cascades; conversely, 36% of 1,248 North Cascade species were not found in the Olympics. Hitchcock and Cronquist (1973) was used to identify plants in both areas.

As with mammals, the Olympic coniferous flora (15 species) is impoverished compared to the Cascades. Five coniferous tree species found in the Cascades are absent from the Olympics (noble fir [Abies procera], ponderosa pine [Pinus ponderosa], subalpine larch [Larix lyallii], western larch [L. occidentalis], western juniper [Juniperus occidentalis]).

Other Taxa

We are reluctant to carry comparisons of taxa much beyond mammals, birds, and selected vascular plants because other components of the biota are less well studied. We note, however, that the distribution of butterflies is comparatively well known and that they too show reduced diversity; about 70 species occur in the Olympics compared to 124 in Washington's Cascades (Scott 1986; tallied by G. Hunter, Olympic National Park, personal communication, 1992). Additionally, Leffler (1979a) reported that tiger beetle (Coleoptera:Cicindelidae) diversity of the Olympics was surprisingly depauperate compared to mainland areas of the Pacific Northwest.

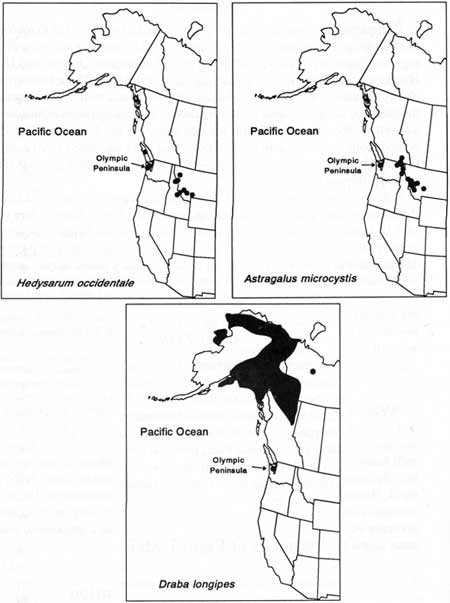

Patterns of Plant Distribution

Several plants found in the Olympics exhibit intriguing disjunct distributions, particularly some of those not found in the Cascades (Fig. 12). Western hedysarum (Hedysarum occidentale) occurs on the peninsula, on Vancouver Island, and 500 km east in the mountains of Idaho; least-bladdery milkvetch (Astragalus microsystis) occurs on the peninsula and from northeastern Washington (350 km east) into Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia; long-stalked draba (Draba longipes) is separated approximately 600 km from populations in northeastern British Columbia. The latter two taxa are known from only one or two locations in the subalpine and alpine zones in the dry northeastern Olympic Mountains.

|

| Fig. 12. Three examples of Olympic Peninsula plant species with disjunct distributions. |

Another phytogeographic pattern of interest includes plants at or near the southern extreme of their range along the Pacific Coast (Fig. 13). Deer cabbage (Fauria crista-galli ssp. crista-galli) occurs from the Olympics (and one point just south) along the coast to southeastern Alaska and the Kenai Peninsula. Cooley's buttercup (Ranunculus cooleyi) is present in the Olympics and in two populations in the Cascade foothills but occurs mainly from Vancouver Island north to the Queen Charlotte Islands. Large-headed sedge (Carex macrocephala) occurs along the coast from Oregon to the Alaska Peninsula and in Japan and China.

|

| Fig. 13. Olympic Peninsula plants at or near the southern extreme of their range. |

Preliminary investigations of the distrbution of lichens reveal at least one on the peninsula (Cetraria tilesii) that is disjunct from the Rocky Mountains (K. Glew, University of Washington, Department of Botany, Seattle, personal communication, 1993). Also, several fungi are apparently disjunct from eastern North America (J. Ammirati and T. O'Dell, University of Washington, Department of Botany, Seattle, personal communication, 1993).

Interpretation

The biogeography of the Olympic biota, including the historical absence of mountain goats, can be viewed within the broader geographical context of the entire glaciated west coast of North America. About 15,000 B.P., the Cordilleran ice sheet extended along coastal North America from Alaska's Aleutian Range south through British Columbia to the Olympics (Fig. 14). Sea level was some 85-130 m lower than at present; consequently, large areas of the continental shelf were exposed (but mostly ice covered). Ice-free areas occurred as coastal refugia and nunataks (isolated mountain peaks projecting above the ice); these areas provided sites where populations of some plants and perhaps animals persisted.

|

| Fig. 14. The maximum proposed extent of Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets. Modified from Denton and Hughes (1981) and Booth (1987). |

Locally, the Olympics were partially overrun by ice on the northern and eastern sides, and the coastal plain extended 20-50 km farther west (see Fig. 3). South of the mountains, enormous, braided outflow channels from the Puget lobe of ice drained west into the Chehalis River and Grays Harbor (Waitt and Thorson 1983). Consequently, although still peninsular during full glacial times, the Olympic area may have been more insular in character, especially related to the dispersal of terrestrial animals. This condition persisted even after the ice began to retreat. During glacial retreat, the Puget Trough was occupied by a dynamic complex of large, proglacial lakes that also drained to the southwest until the ice melted beyond the northeastern edge of the Olympics (about 13,000 B.P.), when the trough again became a marine embayment (Thorson 1980).

The familiar coastline of western North America did not emerge until 10,000-7,000 B.P. (most likely 8,400-8,000 B.P.; Mayewski et al. 1983) following melt of most of the ice and the consequent rise in sea level (Fig. 15). Before this, the currently existing islands along the coast (e.g., the Alexander and Queen Charlotte archipelagos, and Vancouver Island) were continental; today these are classed by biogeographers as landbridge islands because of the former connection.6

6The Kodiak archipelago in south-central Alaska apparently had no land bridge connection during late Wisconsin times (Karlstrom and Ball 1969; D. Mann, Department of Geology, University of Washington, Seattle, personal communication, 1992).

|

| Fig. 15. The Pacific Northwest coastline (dotted line) and the Cordilleran ice at approximately 10,000 B.P., before separation of the landbridge islands. Modified from Mayewski et al. (1981) and Pielou (1991). |

Endemism

Mammals

The degree of differentiation among terrestrial mammals on the Olympic peninsula (one endemic species, four subspecies) is roughly comparable to that of the landbridge islands. Thus, Vancouver Island has 1 endemic species (a marmot) and 11 subspecies; the Queen Charlottes had 1 species (extinct caribou) and perhaps 5 subspecies (others in dispute); the Alexander Archipelago has 11 subspecies (Hall and Kelson 1959; Cowan and Guiget 1965; Foster 1965).

Mammals are notoriously plastic genetically and, given a measure of isolation, are capable of differentiating into subspecies within just a few millennia or perhaps even centuries (Rausch 1969; Berry 1986). Much of the differentiation reported for the landbridge islands most likely occurred in less than 8,000 years. We do not know if any of the endemic mammals of the Olympic Peninsula persisted locally during the late Wisconsin glaciation or if all the differentiation occurred during post-Pleistocene time, which seems plausible.

Plants

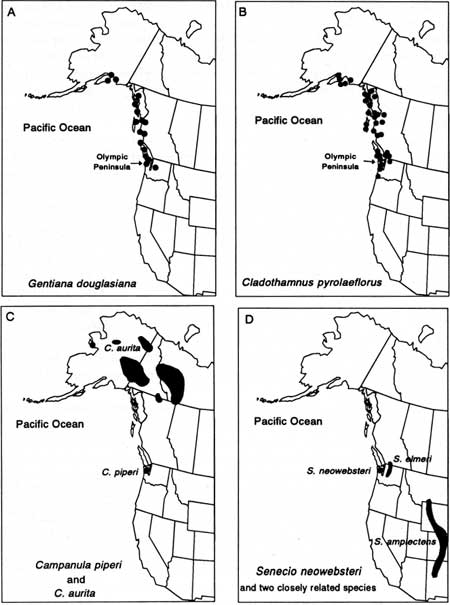

The Olympic Peninsula and the landbridge islands all have endemic vascular plants: the Queen Charlottes have two (Newcomb's groundsel [Senecio newcombei] and Queen Charlotte violet [Viola biflora ssp. charlottae]); Vancouver Island has two (Macoun's meadow-foam [Limnanthes macounii] and wood lily [Trilium ovatum forma hibbersonii]; Szczawinski and Harrison 1972; Straley et al. 1985); and the Olympics eight. However, patterns of vascular plant and mammal endemism differ in that some endemic plants are shared among landbridge islands and the peninsula. Vancouver Island shares four endemic plants7 with the Queen Charlottes and six with the Olympics. In addition, at least four coastal endemics occur within the area extending from southeastern Alaska to the Olympic Peninsula (swamp gentian [Gentiana douglasiana], copper bush [Cladothamnus pyrolaeflorus; Fig. 16], handsome shooting star [Dodecatheon pulchellum ssp. macrocarpum], and deer cabbage).

7Calder's lovage (Ligusticum calderi), isopyrum (Isopyrum savilei), Schofield's avens (Geum schofieldii), and Taylor's saxifrage (Saxifraga taylori: Straley et at. 1985).

|

| Fig. 16. Distributions of two Pacific Northwest coastal endemic plants (A and B) and two Olympic Peninsula endemics shown with their closest relatives (C and D). |

Plant geographers have categorized endemic plants as neoendemics (relatively new, like the peninsula mammals) or paleoendemics (relictual taxa that have existed for a very long, but indeterminate, time; Cain 1944; Stebbins and Major 1965; Daubenmire 1978; Kruckeberg and Rabinowitz 1985). The differences between the two types are believed to be tied to rates of evolution; rapidly evolving forms favor neoendemism, and slowly evolving forms favor paleoendemism (Daubenmire 1978). Debate continues as to how the two types can be differentiated (Kruckeberg and Rabinowitz 1985). We suspect that the Olympics contain plants in both categories, but detailed genetic and distribution studies are required before determinations can be made. Piper's bellflower (Campanula piperi), for example, may be paleoendemic because the closest related species occur more than 1,000 km north (Fig. 16). Conversely, Olympic Mountain groundsel (Senecio neowebsteri) may be a relatively new species because a closely related species exists in the nearby Cascade Range. In general, wide gaps in distribution are thought to characterize paleoendemics (Daubenmire 1978).

The evolutionary and biogeographical histories of the endemic vascular plants and animals on the peninsula may differ. Endemic forms of mammals may have evolved in situ on the peninsula. But the presence of endemic plants shared among the landbridge islands and peninsula suggests at least two other scenarios for plants: (1) taxa shared by two or more islands may have evolved on mainland North America as part of a larger metapopulation that was subsequently reduced, and (2) endemic plants evolved in situ in one location and dispersed to adjacent islands or the peninsula but not to the mainland. The first alternative may explain the overlapping flora of the Queen Charlotte and Vancouver Island archipelagos because the distance between the two is about 240 km, whereas from the mainland, the Queen Charlottes are only 80 km and Vancouver Island is less than 10 km. It is difficult to imagine plants dispersing 240 km and not crossing the shorter distances. The appropriate scenario for the shared Vancouver Island-Olympic endemics is not clear because all distances are comparatively short (20 km or less).

Regardless of which evolutionary scenario is correct, endemic plants likely survived the last glaciation on nunataks or a coastal strip laid bare by the lower sea levels. Plant endemism is virtually unknown from mainland British Columbia,8 which was covered by Cordilleran ice (Clague 1989). Nunataks and coastal refugia were important features on the Queen Charlottes and on Vancouver Island (Warner et al. 1982; Pielou 1991). The Olympic Peninsula was probably part of the same refugial system. Endemism in carabid beetles follows a similar pattern (Kavanaugh 1992).

8British Columbia has 14 endemic plants—10 occur on Vancouver Island and/or the Queen Charlottes; only 1 is found exclusively on the mainland (Straley et al. 1985).

Support for the nunatak—coastal refugium hypothesis also is found in the bimodal distribution by elevation of plants endemic to the peninsula. Two species occur at low elevations on the coast in areas thought to have been ice-free (Heusser 1977). The remaining endemics occur at elevations that exceed the maximum elevation of Cordilleran ice. We are uncertain of the extent of ice in the Olympics during the Evans Creek glacial period, but most high elevation endemics occur mainly on rock outcrops and ridge tops, which were likely free of ice and of persistent snow during that stade.

Species Diversity

Mammals

In common with the Olympic Peninsula, landbridge islands have impoverished faunas compared to the adjacent mainland (Table 3). Vancouver Island has 16 species of indigenous terrestrial mammals and 19 species that are absent (Cowan and Guiget 1965; Lawlor 1986). The situation on Alaska's Alexander Archipelago is more complex, but up to 18 species are absent from one or more of the islands compared to the mainland. The Queen Charlottes had only seven species of indigenous terrestrial mammals (wandering shrew [Sorex vagrans]; black bear [Ursus americanus]; marten [Martes americana]; short-tailed weasel [Mustela erminea]; white-footed mouse [Peromyscus maniculatus]; otter [Lutra canadensis]; and Dawson caribou [Rangifer dawsoni]; Cowan and Guiget 1965; Foster 1965).

Table 3. Terrestrial mammals absent from Vancouver Island and the Alexander Archipelago when compared to faunas on the adjacent mainland.a

| Vancouver Island | Alexander Archipelago |

| Cinereus shrew, Sorex cinereus | Water shrew, Sorex palustris |

| Coast mole, Scapanus orarius | Collared pika, Ochotona collaris |

| American pika, Ochotona princepsb | Snowshoe hare |

| Snowshoe hare, Lepus americanus | Hoary marmot, Marmota caligata |

| Mountain beaver, Aplodontia rufa | Northern flying squirrelc |

| Northwestern chipmunk, Tamias amoenus | Northern bog lemmingb,d |

| Bushy-tailed wood rat, Neotoma cinerea | Northern redback vole |

| Northern bog lemming, Synaptomys borealisb | Meadow vole, Microtus pennsylvanicuse |

| Boreal redback vole, Clethrionomys gapperi | Tundra vole, Microtus oeconomuse |

| Long-tailed vole, Microtus longicaudus | Muskrat |

| Muskrat, Ondatra zibethicusf | Meadow jumping mouse, Zapus hudsonius |

| Porcupine, Erethizon dorsatumb | Porcupineb |

| Coyote, Canis latrans | Coyote |

| Red fox, Vulpes vulpesb | Red foxb |

| Grizzly bear, Ursus arctosb | Wolverine, Gulo gulob |

| Fisher, Martes pennanti | Lynx, Lynx lynxb |

| Spotted skunk, Spilogale gracilis | Moose, Alces alces |

| Striped skunk, Mephitis mephitis | Mountain goat, Oreamnos americanusb |

| Bobcat, Lynx rufus | |

| Mountain goatb | |

| Northern flying squirrel, Glaucomys sabrinus | |

aData from Cowan and Guiget 1965 and Manville and Young 1965. bAlso absent historically from the Olympic Peninsula. cAbsent from Chichagof, Admiralty, and Baranof islands only. dOccurs only on Admiralty Island. eAbsent from Prince of Wales and Kuprenof islands only. fSubsequently introduced. | |

Mammals missing from the landbridge island faunas include species that were absent historically from the Olympics as well—the mountain goat included. As with the Olympics, the mammal absences mean either that the species failed to colonize because of environmental barriers or that earlier populations met extinction. The success of deliberate introductions suggests that unoccupied habitat may exist for additional species. Six mammal species have been introduced successfully to the Queen Charlotte Islands: beaver (Castor canadensis), raccoon (Procyon lotor), black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus), muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), elk (Cervus elaphus), and red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus). Three have been introduced to Vancouver Island: eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus), eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis), and muskrat (D. Eastman, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C., personal communication, 1992; D. Nagorsen, B.C. Provincial Museum, Victoria, B.C., personal communication, 1992). The mountain goat has been introduced to Baranof and Chichagof islands within the Alexander Archipelago and to Kodiak Island, and it has become established on at least Baranof and Kodiak (Ballard 1977) and in the Olympic Mountains.

Attenuated faunas characterize true islands, landbridge islands, and habitat islands worldwide (e.g., Heaney and Patterson 1986). Examination of the patterns of mammal distribution on islands has intensified during the past 2 decades. Most advances in understanding have resulted from testing observed patterns of distribution against the equilibrium model of island biogeography developed by MacArthur and Wilson (1967). Their model proposes that the number of species inhabiting an island represents a dynamic equilibrium between rates of colonization and rates of extinction and that the level of the equilibrium (species richness) may be predicted from knowledge of island size and degree of isolation. An enhanced understanding of mammalian biogeography occurred when the observed patterns refuted the predictions of the model (Brown 1986).

Generally, impoverished terrestrial mammalian fauna on landbridge and habitat islands are thought to represent nonequilibrium, relict faunas derived to a large extent from differential extinctions of formerly more widespread species (e.g., Brown 1971, 1986; Patterson 1984; Lawlor 1986). But questions remain, including the relative importance of extinction versus (failed) colonization in producing any particular assemblage of mammals, and the extent to which water and unsuitable terrestrial landscapes function as barriers to mammal colonization (Brown 1986).

The impoverished nature of the terrestrial mammalian fauna of the Olympics is to be expected. We do not know the relative contributions to the present fauna of extinction versus the failure to colonize. No obvious characteristics or relations have been identified that are common among species absent from the peninsula and from the landbridge islands that would similarly predispose populations to extinction (e.g., pikas [Ochotona spp.], bog lemming [Synaptomys borealis], porcupine, red fox, mountain goat). Density, demography, and ecological requirements differ widely among the five species. Failure to colonize might be as plausible an explanation as extinction in accounting for the absence of the four species (porcupine excepted) that occupy subalpine and alpine habitat; extensive bodies of water and forest may have represented effective barriers to colonization. Other regional examples of geographic barriers affecting mammal distribution include the greater richness of the terrestrial mammal fauna of western Oregon (10 additional species) compared to western Washington; the Columbia River apparently serves as an effective barrier to colonization (Dalquest 1948).

Plants

The overall diversity of vascular plants on the peninsula seems unremarkable when compared with the situation for terrestrial mammals. However, coniferous tree species diversity on the peninsula is reduced compared to the Cascade Range—a pattern of impoverishment similar to the mammals. We can not compare other taxonomic groups until the various floras are standardized.

Patterns of Plant Distribution

The disjunct and coastal distributions of vascular plants in the Olympics support geologic evidence for the occurrence of glacial refugia. We do not know how widespread these species were in the past, but their modern distributions seem to be limited to areas thought to have been ice-free during at least the Vashon stade of the Fraser glaciation. For example, the long-stalked draba occurs in the Olympics and in what was southeastern and southern Beringia (Guthrie 1990; Pielou 1991). Western hedysarum, a western North America endemic, occurs in the mountains of Idaho just south of the former Cordilleran ice, on Vancouver Island, and in the Olympic Mountains.

The distributions of closely related species also help interpret prehistoric events. Guthrie (1990) observed that the break in the distribution of closely related mammalian species such as pikas corresponded to the area covered by Cordilleran ice during the Vashon stade of the Fraser glaciation: He hypothesized that two species, Ochotona princeps and O. collaris, were a single taxon before invasion of the ice sheet and that they evolved into different species as a result of separation by the ice. A similar pattern is found in the distribution of species closely related to the endemic Piper's bellflower of the Olympics. The closely related bellflower (Campanula aurita) is found on the British Columbia—Yukon border and north—a distribution not unlike that of the pika. We do not know how long the Campanulas have been separated, but their distribution provides further evidence of glacial refugia in the Olympics.

Synopsis

Overall, species diversity and endemism characteristic of the terrestrial mammalian fauna on the Olympic Peninsula seem broadly comparable to landbridge islands along the glaciated west coast of North America. It is the particular assemblage of extant and endemic forms that renders the Olympic fauna unique. Species absent historically from the Olympics were also absent from landbridge archipelagos.

Endemism in vascular plants and the depauperate coniferous flora of the Olympic Peninsula is roughly similar to the patterns of mammals on landbridge islands. However, the shared endemism (among plants on the landbridge islands and the peninsula) and the occurrence of strongly disjunct plant species suggest that glacial refugia played an important role in phytogeography. Whitlock (1992) suggested that the Olympics could easily have provided the germ plasm for recolonization of the Puget Trough and points north as the Cordilleran ice receded. The Olympic biota is unique today and may well have served in the past as an important biological reservoir.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap3.htm

Last Updated: 12-Dec-2007