CAPE LOOKOUT

Barrier Island Ecology of Cape Lookout National Seashore and Vicinity, North Carolina

NPS Scientific Monograph No. 9

|

|

CHAPTER 3:

OVERWASH STUDIES AT CAPE LOOKOUT NATIONAL SEASHORE (continued)

INLET DYNAMICS

Inlets, permanent or temporary, are an integral part

of the barrier-island environment. Permanent inlets are usually opposite

the mouths of major rivers and let river water into the sea. Temporary

inlets shift position frequently, depending on storms and sand movement.

Fisher (1962) described the historical patterns of both kinds of inlets

on the Outer Banks and showed that nearly all the islands have been

broken by inlets, even though only a few existed at any one time; 14

have been present at various times between Ocracoke Inlet and Barden's

Inlet. Temporary inlets form when a storm first drives high water across

an island. As the storm passes and the wind blows from the opposite

direction, water in the sound is forced back over the island at low

places, and may divide the beach on the way. Water can then flow back

and forth until sand carried by the littoral drift eventually plugs the

inlet. While the inlet is open, exchange between the sound and the sea

benefits both ecosystems. The life of the new inlet depends on tidal

flow, the depth of the sea and sound waters, the frequency of storms,

and the amount of littoral transport. Broad shoals build up in the sound

behind the inlet until they impede tidal scouring. The updrift side of

the inlet usually migrates in the direction of the littoral flow while

the downdrift side erodes. If migration of one side is faster than

erosion of the other, the inlet eventually closes. The shoals behind are

then invaded by salt marsh grass, and new marshes appear over a wide

area that was once open water. Overwash and dune growth build up the new

land and soon all superficial traces of an inlet disappear.

Such a pattern may be seen on Core Banks where Drum

Inlet used to be. This inlet, opposite Atlantic, N.C., has had the usual

history of opening and closing. It was open in the early 1800s and

closed in the mid-1800s, only to open again in 1933 during the great

hurricane of that year. It remained open until 1971, migrating southward

nearly a mile, and building broad shoals in the sound (Fig. 38). The

tides no longer regularly flooded these shoals, and small dunes started

in the middle of the shoals where sand blown off the bare flats

accumulated around sprigs of Spartina patens (Figs. 39, 40). The

shoals are now being colonized rapidly by Spartina alterniflora

(Fig. 41). Figure 44 is a map of the areas being colonized by plants and

the locations of cores which demonstrate that the shoal material was

definitely marine. In December 1971, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

opened a new inlet about 4.5 km south of the old inlet and reestablished

a regular tidal cycle in Core Sound.

|

|

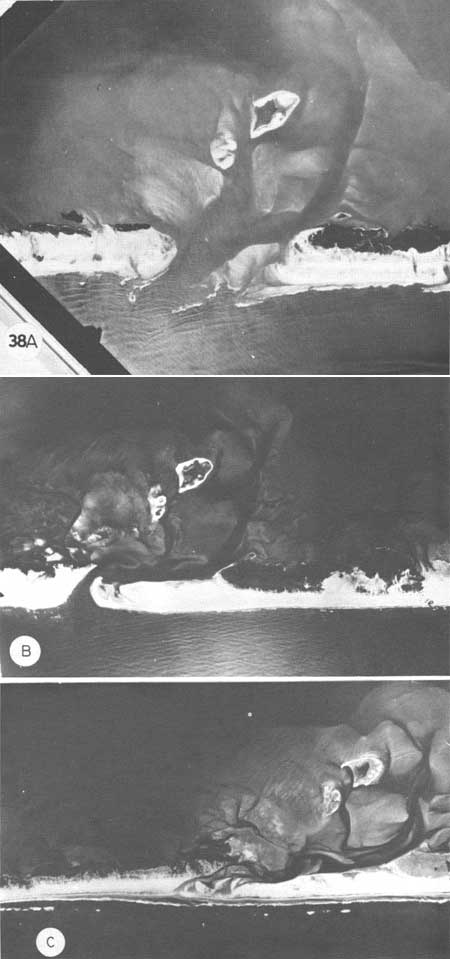

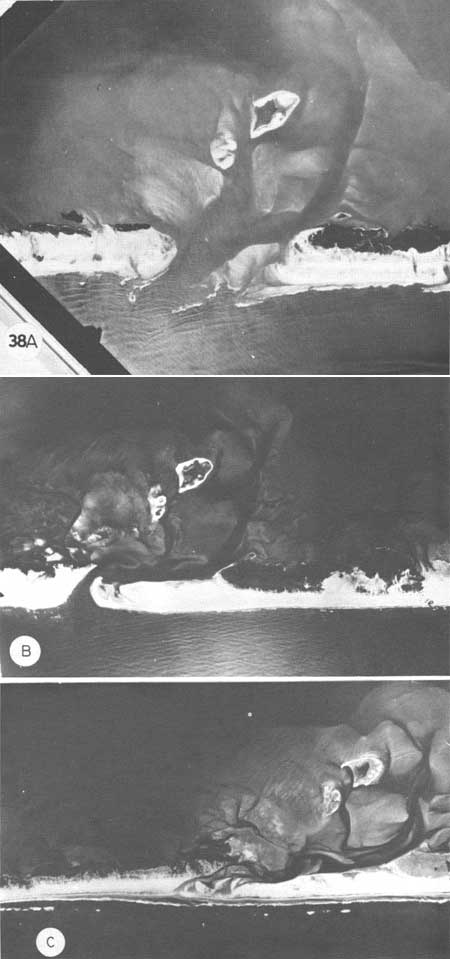

Fig. 38. Drum Inlet closing. (A)

28 October 1958, Drum Inlet was opened by the great 1933 hurricane and

was then dredged from time to time. When this photograph was taken,

several severe storms created numerous inlets which soon closed.

Littoral drift is from the right to the left. A spit can be seen forming

on the updrift side of the inlet; large deltaic shoals have appeared.

Southwest is to the left in this photograph. (B) 24 August 1963.

The updrift spit has migrated nearly all the way across the inlet. Tidal

channels have become sinuous and shoals have continued to build. The

downdrift side has been eroded. Buried layers of marsh peat were

exposed where the channel cut through the berm, as well as on the beach;

this is further evidence of general barrier island retreat. (C)

11 February 1971. The updrift spit migrated faster than the downdrift

side eroded, and finally sealed off the inlet in January 1971. Overwash

began filling in the low areas behind the former channel. With the

growth of the updrift spit, the inlet channel migrated 2 km southwest

since 1958, following the normal pattern of inlet migration toward the

south or west depending on the orientation of the islands.

|

|

|

Fig. 39. View of Drum Inlet in June

1971, halfway down the spit which closed the inlet. Much of the berm is

barren, although dunes are growing up along the backside. Dunes are well

established where the spit is oldest. Beyond the old channel are broad

shoals exposed at low tide. The towns of Atlantic and Cedar Island.

North Carolina, are on the horizon.

|

|

|

Fig. 40. The older shoals associated

with the Drum Inlet tidal delta are being invaded by Spartina

alterniflora (in the foreground) and low dunes with Spartina

patens, Fimbristylis spadicea, and Erigeron pusillus to the

left. The broad, bare shoals provide sand for dune growth when they dry

out at low tide.

|

|

|

Fig. 41. Large shoals behind the former

inlet are being colonized by saltmarsh cordgrass, Spartina

alterniflora. and blue-green algae, the dark patch in the

foreground. In time, these shoals will become highly productive salt

marshes. They are already heavily populated with fiddler crabs and are

important feeding grounds for birds.

|

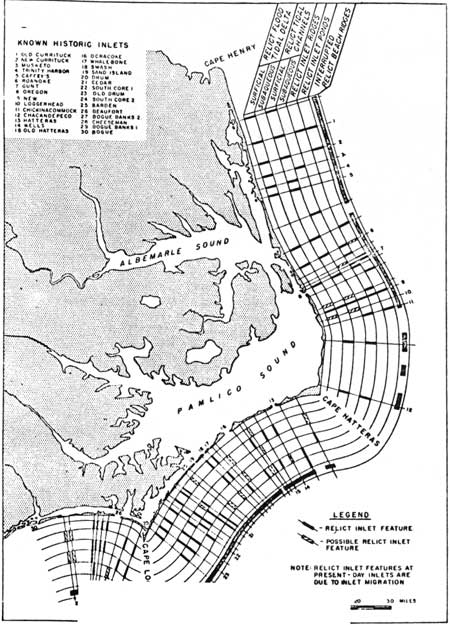

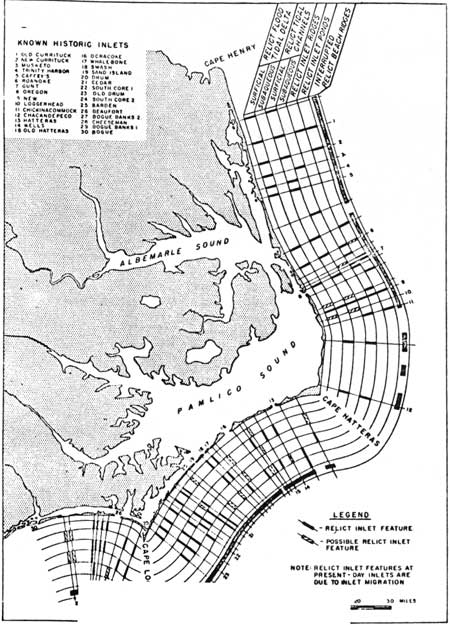

Maps of the early 1800s and local documents show the

site of Cedar Inlet a few miles south of the Drum Inlet area. By 1850,

this inlet was completely closed, although its location was marked on

the map (Fig. 45). We were able to locate Cedar Inlet (Fig. 42) and make

several cores through three of the marsh islands in Core Sound behind

the old inlet. The layers of peat were relatively shallow; underneath we

found surf shells, so these marshes had their beginnings on shoals that

formed when sand and shells from the beach were carried into the inlet.

From the direct evidence of Drum Inlet and Cedar Inlet, with the

patterns of marsh islands behind the barriers and the deep channels

between these islands that end abruptly behind the barrier (Fig. 43), it

seems clear that various parts of Core Banks contained inlets at one

time or another (Fig. 46), and that the closing of inlets rapidly widens

low barrier islands by a factor of 2 or 3. Overwash then fills in the

low places, connects marshes as the island retreats, and continues the

building process. Dunes constantly form, are knocked down, and then

reform. Thus inlets, overwash. and dune growth are processes by which

the barriers are built, maintained, and migrate as the sea rises (Fig.

46A). Much of what we see today on the Outer Banks is of very recent

origin and definitely marine, even though the islands may have been

formed originally by some other means. A stump we found in place on the

seaward side of Shackleford, visible only at high tide, turned out to be

less than 200 years old by Carbon-14 dating (Sample W-2307, U.S. Geol.

Survey) (Fig. 14).

|

|

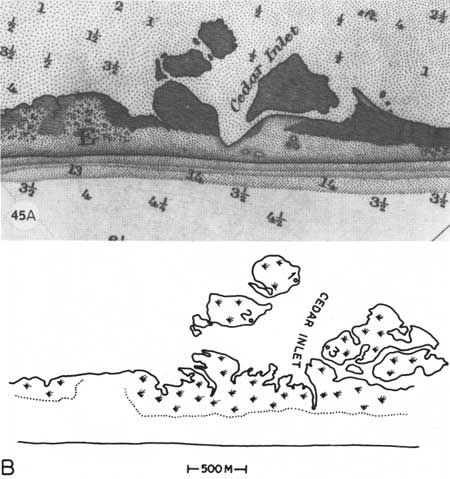

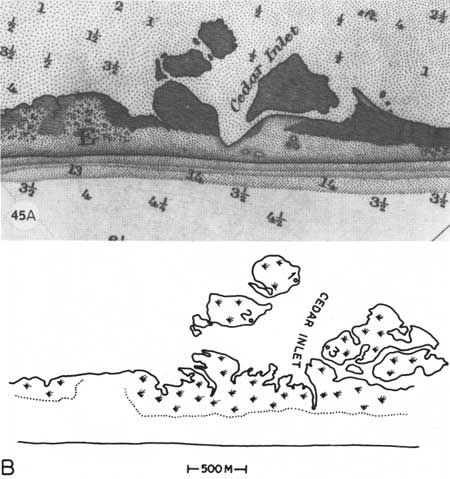

Fig. 42. Site of Cedar Inlet, open from

the 1700s to the early 1800s, The marshes and creeks follow a pattern

which suggests that they developed on former tidal delta shoals. Cores

from these marshes showed peat layers about 50 cm thick underlain by

fine sand and shells. The shells included the same surf species as were

found in the Drum Inlet shoals, which is direct evidence that the Cedar

Inlet marshes developed on sand and shells that moved down the beach in

the littoral drift and then into the inlet, much as at Drum Inlet. When

the inlet closed, marsh growth proceeded unhindered by tidal surges. The

dark areas are underwater beds of widgeon grass (Ruppia maritima)

and eelgrass (Zostera marina).

|

|

|

Fig. 43. Guthries Hammock seems to be

located at a former inlet, although there is not yet any direct evidence

for this. The former channel is probably the creek at the upper left. A

migrating spit sealed off the inlet on the right side and a continuous

berm built up. The dark patches are stands of live oak (Quercus

virginiana), holly (Ilex opaca), and other forest species

growing on old dunes. It seems likely that these old dunes may have

started on barren shoals much like the present sequence at old Drum

Inlet. In time the dunes were colonized by the tree species, thus

culminating the successionary sequence from tidal delta shoals, to

grassy dunes and marsh, to forest and marsh.

|

|

|

Fig. 44. Map of Drum Inlet, summarizing

changes shown by aerial photographs and ground surveys. Figures 40 and

41 were taken on the large shoal nearest the channel marked by the

number "2." Sites 1 and 2 were locations of cores containing surf

shells. Marshes are developing all around the edges of the large shoals

and completely covering the smaller ones. Shoals covered by low tide are

potential substrate for underwater vegetation, such as in the Cedar

inlet area, and are being invaded by those species; a lush stand of

eelgrass was found in the old channel near the letter "h." Inlets are

thus a major means by which the barrier island system widens and large

new salt marshes form.

|

|

|

Fig. 45. (A) The site of Cedar

Inlet as shown in the 1888 issue of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey

chart. The former channel is well marked on this map. (B) The

present site taken from a 1963 aerial photograph. What was once the

channel has been filled by overwash deposits. Numbers on the marshes

refer to locations of cores described in Fig. 42.

|

|

|

Fig. 46. Missing text. (click on

image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

|

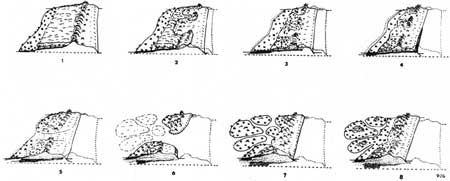

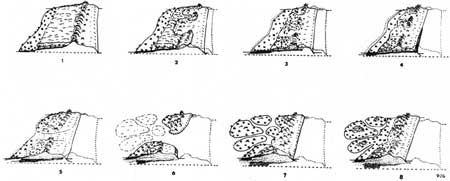

Fig. 46A. Generalized summary of harrier

island dynamics and migration (vertical scale exaggerated). Stage 1 is a

hypothetical barrier island which may have existed anywhere from present

times to several thousand years ago, with a well developed dune line, or

series of dunes, and a forest behind. In stage 2, the sea level has

risen slightly and storms have knocked the dune barrier back into the

woodlands. By stage 3, much of the barrier island has been overwashed

and the dunes pushed back. The marsh has grown vertically and been

somewhat eroded, and some former uplands are now salt marsh as a result

of sea level rise. In stage 4, the barrier has retreated considerably

from its original position. Dune and overwash sand has moved completely

over the old forest, which is now exposed on the ocean side. Marshes

near the island interior have been covered as well. Further retreat

places sand completely over the original marsh surface and into the

lagoon behind, where new marshes form. At stage 6 an inlet has opened

and a typical tidal delta has appeared behind it. The temporary inlet

has closed in stage 7, and the tidal delta now supports salt marsh and

low dunes. Overwashes have tied the marsh islands to the main barrier

and have filled in the old channels in stage 8. The salt marshes are now

well developed on the old tidal delta, woods have grown upon the low

dunes on these marsh islands, the salt marsh fringe behind the barrier

is expanding, and on the barrier itself new dune lines and woodlands

have formed where only a short time ago there was water. (click on

image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

chap3e.htm

Last Updated: 21-Oct-2005

|