|

CAPE LOOKOUT

Barrier Island Ecology of Cape Lookout National Seashore and Vicinity, North Carolina NPS Scientific Monograph No. 9 |

|

CHAPTER 3:

OVERWASH STUDIES AT CAPE LOOKOUT NATIONAL SEASHORE (continued)

BARRIER-ISLAND VEGETATION

Because of limited time and space, the following discussions of barrier-island vegetation will be rather superficial and will be confined to the terrestrial communities. Obviously, marine communities surrounding the islands are of considerable importance; these will be dealt with in the future.

It should be noted that the systems described here are basically those of Cape Lookout National Seashore; the barrier islands to the north and south of Cape Lookout vary from those discussed here, although there are certain basic similarities. Such variations will be described in future publications.

GENERAL ZONATION PATTERNS

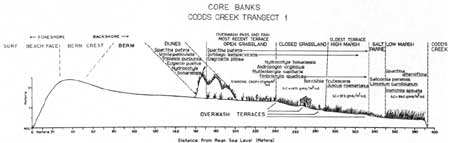

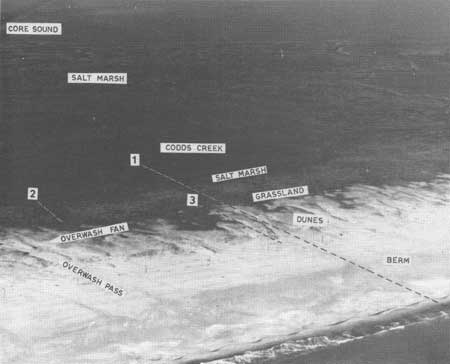

The major ecosystems of the undeveloped, and to some extent of the stabilized, Outer Banks fall into five basic types: beach and berm, maritime grasslands, woodlands, fresh marshes, and salt marshes. Other types to be described result from various topographic conditions which modify or add to the basic five. A typical barrier-island zonation pattern can be seen at the Codd's Creek section of Core Banks, shown in Figs. 47 and 48. As one proceeds from the ocean side, the first zone is the bare berm and beach system, its width depending on island orientation, storm frequency, and human interference, as will be described later.

|

| Fig. 47. Codds Creek study area, showing general features of a low barrier island and the zonation of its ecosystems. The dotted lines correspond to transects through an overwash pass and fan; the main profile, #1; overwash salt marsh, #2 and #3. Dunes are shown in Figs. 25 and 48, and the dunes and overwash salt marsh in Fig. 27. Darker patches in salt marshes are stands of Junius roemerianus. |

As shown in Fig. 48, the highest elevation of the island is generally the berm crest and the land slopes back from there. However, where dune building is active, elevations will be higher, but the berm crest remains a constant set by tides. The next zone is the dune strand, which may be of a very open and low type or more closed and higher, again depending on orientation to prevailing winds, storm effects, and human interference. Between and behind the dunes are extensive barrier flat grasslands on overwash deposits, with vegetation increasing in density and cover as one proceeds to the back side of the island. Such grass lands are dominated by a few species tolerant of flooding and burial.

In the more stabilized areas, a zone of woody plants appears between the grassland and the high salt marsh, usually as shrub thickets on the flats, but sometimes taking the form of maritime woodland on older dunes. Fresh-water marshes and ponds are frequently found between dune systems or in low areas on the barrier flats protected from tidal action. Such localized wetlands are most common where interdune slacks are well developed, such as on Shackleford. Perhaps the most extensive wetland system along most of the barrier island chain is that of the intertidal salt marshes which occupy low islands behind the barrier and form an intertidal fringe on the lagoon side of the barrier itself. The following discussions will deal with each type in more detail.

I. Bare Berm and Beach:

The most rapidly changing, semiterrestrial habitat is the sand beach within reach of high tide. This is no place for rooted plants or sessile animals; it is basically a detritus ecosystem populated by burrowing animals such as Donax (coquina), Emerita (mole crabs), interstitial amphipods and isopods, and feeding shorebirds. Primary productivity in the intertidal beach is limited to unicellular algae.

The berm environment is controlled in large part by the frequency of storms and is only slightly more stable than the beach itself. The vegetation is widely scattered; annuals, such as Cakile edentula (sea-rocket), Amaranthus pumilus (seabeach amaranth), Salsola kali (Russian thistle), Euphorbia polygonifolia (sea-side spurge), and Polygonum glaucum (seabeach knotweed), germinate most often from seeds in drift lines washed up during winter storms. The perennial beach grass Uniola paniculata (sea oats) also germinates in the drift lines and small dunes appear, which build until a storm either knocks them down or buries them. As for animals, shorebirds commonly nest on the berm, and the usually nocturnal ghost crabs scavenge in broad daylight on the relatively wild Core Banks.

The width and general nature of the beach-berm system vary considerably along the Outer Banks, and especially on those sections where artificial dunes have been built out on the original berm. The natural beaches typically have a wide berm zone ranging between 100 and 200 m, as shown in Fig. 49, which is rather consistent the length of the barrier. On those islands, such as in Cape Hatteras National Seashore, where dune lines have been built on the original berm, the width of the system is greatly reduced (Fig. 50). In some cases, where erosion is now a problem, the berm crest and backslope no longer exist and the high tide comes up to the dune (Figs. 52 and 54). In contrast to "stabilized beaches," the natural berms of Core Banks and Cape Lookout are wide and frequently reworked by storm tides (Fig. 51). In some sections, small dunes are developing on the berm (Fig. 53), but these are frequently knocked down or buried as storm tides wash over the berm crest and across the island. Other stretches are duneless and wide (Fig. 55). The widest berm zones occur on Portsmouth Island, where the land slopes back across barren stretches of sand to the high-tide mark on the sound side (Fig. 56). Where the berm ends and the bare sand flats begin is hard to determine because the slope is very gradual. These broad, bare flats may be the result of overgrazing in the past, since vegetation is now invading certain portions, and dunes, marshes, and grasslands are developing. Further research is needed to decide to what extent the condition is man-caused.

|

| Fig. 49. Aerial view up Core Banks just north of the Cape Lookout Lighthouse, showing the uniform width (about 150 m) of the berm on this undeveloped beach. The width is set by major overwashes and their frequency. The light color along the back of Core Banks is ice, a rare occurrence in these waters. Sand waves along the beach are visible near the top of the photograph. The dark gray (almost black) zone bordering the lighter gray in the center of the island is a dense shrubland, frequently found running between the salt marshes to the left and grassland and dunes to the right. |

|

| Fig. 50. The berm on developed beaches is narrow and irregular where it exists at all. The continuous dune line directly affects the width of the berm and prevents a normal berm development. The view is of Hatteras Island at Sandy Bay in Cape Hatteras National Seashore. (Photo by Cape Hatteras National Seashore Staff.) |

|

| Fig. 51. Cape Lookout Lighthouse, built in 1859, showing the normal wide berm and dune line between the building and the beach. Storm waters are free to move right over the island and no erosion is apparent in the 113 years since the lighthouse was built. |

|

| Fig. 52. The location of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse contrasts sharply with Cape Lookout. When this photo was taken 17 April 1970, the berm was non-existent. Groins under construction later caught sand, but caused other problems down drift. Storm waters are stopped at the dune line, In recent years much effort and money have been expended to keep the lighthouse from falling into the Atlantic Ocean. At Cape Lookout nothing at all has been done, yet that lighthouse is safe for the forseeable future. The artificial dune line clearly exacerbates the erosion problem. (See Dolan in press.) (Photo by Cape Hatteras National Seashore Staff.) |

|

| Fig. 53. Berm environment opposite Cape Lookout Lighthouse, largely bare although scattered dunes of Uniola paniculata are forming. |

|

| Fig. 54. Contrasting with Fig. 53 is the beach on Hatteras Island opposite motels in Buxton. The berm is gone and high tide nearly reaches the dunes. Storms have cut away the dune line dramatically and stimulated expensive beach nourishment projects. |

|

| Fig. 55. Much of the berm on Core Banks, here looking north with Guthries Hammock on the left opposite Davis, North Carolina, is barren and frequently overwashed. |

|

| Fig. 56. Vast reaches of Portsmouth Island are without dunes or vegetation (See Fig. 10F) and are therefore being lowered by wind and overwash. The remains of a ship are in the foreground, a small marsh island in the distance, and Portsmouth Village in the far distance. Some marsh vegetation is slowly invading the back side of Portsmouth Island between the established marshes. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap3f.htm

Last Updated: 21-Oct-2005