|

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

Selected Papers From The 1985 And 1986 George Rogers Clark Trans-Appalachian Frontier History Conferences |

|

BLACK ROBES AND BLACKENED FACES: A HISTORY OF MIAMI-JESUIT RELATIONS

Peter Peregrine

Purdue University

I had still further every reason to be surprised and delighted at the tokens of endearment which I had received from most of these people, instead of the hatchet-blows that I expected; and, more yet, at the simplicity of a good old man in whose cabin I publicly explained the holy Mysteries of the Incarnation and Death of JESUS CHRIST. As soon as I produced my Crucifix, to display it before the people's eyes, this good man, moved at the sight, wished to acknowledge it as his God, and to worship it by an offering of the incense of this country. It consisted of powdered tobacco, of which he took two or three handfuls, one by one, and, as if offering the censer an equal number of times, scattered it over the Crucifix and over me — which is the highest mark of honor that they can show toward those whom they regard as Spirits. I could hardly restrain my tears of joy at seeing the crucified JESUS CHRIST worshiped by a Savage at the very first time when he was told about him. [1]

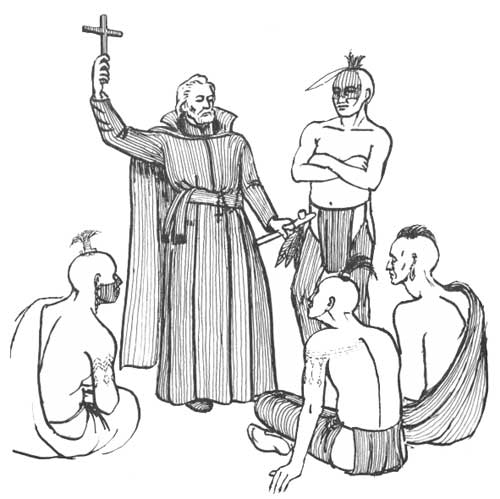

This passage was written in March of 1671 by the Jesuit Claude Allouez from a newly founded mission southwest of Green Bay. It is a striking image — the Jesuit displaying his crucifix for the first time to a group of intrigued Amerinds, hoping to somehow keep their attention, hoping to somehow gain their trust, and on the other side the Amerind, sitting confused before this strange outsider who dressed completely in black and spoke his language with difficulty, obviously quite different from the French traders who had been mistreating men from his village for years. And then the crucifix itself — shining in silver like nothing the Amerind had seen before, representing a strange story of death the man in black was telling, representing somehow a God. One can understand how the Amerind was moved by the experience, and approached the image to honor it in the only way he knew — offer it tobacco.

This offering is perhaps the most striking thing about the passage, though not because the Amerind made it, but because Allouez accepted it, not only accepting it, but crying from joy at the gesture. One has to remember that this was 1671. The Catholic Church was still reeling under the shock of Luther, Calvin, and others. The counter-reformation was in full swing. Altars in Catholic Churches were literally behind bars. Priests gave salvation through formal rites and duties, and offered advice on how parishioners could help the priesthood save them, but religion was in the hands of the clergy, not of the people. Yet here, in the remote wilds of North America, Allouez allowed an Amerind to sprinkle tobacco on a cross, a cross that in Europe might be locked behind an iron gate in a cathedral or the stone walls of a rectory. Why? What was in this relationship that left Allouez crying from joy at an act that might have been heresy in Europe? We cannot forget the Amerind in this situation either. His religious beliefs had at least 10,000 years of independent development behind them, yet were apparently so plastic that, as in the passage above, they could be modified in a moment. Why was this? What motivated the Amerind peoples to accept the Jesuits and their teachings?

These questions concerning the motivations of both the Amerinds and the Jesuits in this contact situation have been the focus of my recent research, [2] and I will offer some interesting, though tentative answers to them. I will concentrate on one Indian group, the Green Bay Miamis, and on the two missionaries, Claude Allouez and Louis André, who were with them during a short period of time, 1669-1679.

The Miami were a Central Algonquian Amerind group, closely related to the Illinois. [3] The first reference we have of them comes from the Jesuit Relations for 1658, where they are mentioned as living with a large group of displaced Amerind peoples around Green Bay. [4] These Miamis were obviously out of place in this setting, and when later asked where they came from they claimed to have been living with the Illinois west of the Mississippi. [5] Archaeological evidence suggests that both the Miami and Illinois are related to the prehistoric Fisher and Huber cultures, and therefore probably inhabited a large region around the southern end of Lake Michigan, extending southward into central Indiana and Illinois. [6] Charles Callender has suggested that the Miami and Illinois represent the descendants of the complex Ohio Valley Hopewell cultures, which would place their homelands further to the south in earlier prehistory although this connection is tenuous. [7]

The reason for the Miami's migrations, both to the west of the Mississippi and (for the Green Bay Miamis) into Wisconsin, seem obvious enough — fear of the Iroquois. We know that the fall of Huronia in 1649 prompted many Amerind peoples of the western Great lakes to move to safer lands The Miamis claimed to have suffered a number of attacks from the Iroquois, which probably spawned their movement west. [8] Attacks from the Sioux in that region drove them finally to Wisconsin, which had become a haven for many frightened groups. Sheltered by Lake Michigan — a significant obstacle for Iroquois raiders from New York and Ontario to traverse or circumnavigate, and far enough away from the Sioux, the area around Green Bay grew to contain a swarming population of displaced peoples, not all of them well equipped for the environment of northern Wisconsin.

Among the peoples not prepared to meet the harshness of the Wisconsin climate were the Green Bay Miamis. Allouez put it simply: "they have greatly suffered in this quarter." [9] The change in environment, along with the great changes that must have already shaken their culture due to tensions and trials of the preceding years of warfare and flight, must have made these Miami people week, scared, and unsatisfied with their culture and their way of life. This may have prepared them to accept cultural change, and perhaps new ideas such as those the Jesuits were introducing. Homer Barnett discusses situations like that being experienced by the Miamis at this time in his study of culture change, Innovation. He explains:

Land alienation and its equivalent, migration, force some cultural readjustments if the dispossessed group is to survive. At the very least adjustments must be made to accommodate for the absence of essentials that were relied upon in the old habitat. . .usually it also results in the utilization of the unfamiliar foods and materials of the new land, adaptations to the climate and the terrain, and, if the new land is inhabited [which, of course, the area of Wisconsin the Miamis had moved to was], the development of economic, social, and political arrangements with the indigenous population. [10]

In short, Barnett claims that "Migrants and dispossessed populations are characteristically receptive to new ideas." [11]

Let us, then, take a closer look at some of those forces that may have been acting on Green Bay Miamis to encourage change at this time. The Miamis came from a fairly temperate environment: oak hickory forest and prairie areas with rich resources to exploit. Moving into the harsher and colder pine forest and riverine areas of Wisconsin, which required an entirely different pattern of subsistence to exploit efficiently, must have been a great strain on them. The Miami would no longer have had a sense of the potentials and limitations of their environment — they would not know how to use their environment wisely or to their greatest benefit. For example, riverine resources were a primary source of food in Wisconsin, yet the Miamis were fearful of water, and were not known to use canoes. The Jesuit Relations tell of huge villages of these refugees on the edge of starvation for months during the harsh Wisconsin winters. [12] In addition, the fur trade was changing the way the Miamis perceived their environment. Once unimportant resources came to be seen as important elements of the environment, and resources that were already of some importance, like beaver, grew to have a much greater place in the Miamis' perceived environmental inventory. These environmental forces must have been great in fostering change in Green Bay Miami culture.

Tied in with the growth of the fur trade were also changes in the Miamis' economy. The Miamis originally were simple horticulturalists, raising corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. Winter bison hunts supplied meat, as did sporadic hunting of deer and small mammals throughout the year. [13] With the growth of the fur trade this simple hand-to-mouth subsistence changed to production for sale. Beavers in particular, once sought after by Amerinds for their abundant fat, began to be exploited for market trade rather than for sustenance, and this pattern was repeated for many fur-bearing species. Although trade with other groups must have been a part of Miami life for thousands of years, production specifically and exclusively for trade had probably never been a large part of the Miamis' economy. With the growth of the fur trade this pattern changed, and some of the Miamis became specialists in production for exchange rather than for consumption. In short, the Miamis' economy was modified as a result of the fur trade.

Environment and economy have been said to be primary in both forming and maintaining a people's ideology or world view. The link between ideology and day to day existence has been explained by Maurice Cornforth in The Theory of Knowledge. He tells us that:

ideology is a reflection of the real, material world in the form of abstract ideas. Every ideology is an attempt made by people to understand and give an account of the real world in which they live, or some aspect of it and of their own lives, so that it may be of service to them in the definite conditions in which they live. Therefore they must always strive to develop their ideology as a coherent system of ideas which squares with the facts so far as they have experienced and ascertained them. [14]

Using this theoretical framework, then we must expect that changes in the basic material aspects of life — the environment, subsistence production and exchange — must lead the way for changes in ideology, and indeed in the entire culture of the peoples concerned. [15]

Needless to say, the upheavals that occurred to the Miami peoples prior to 1669 must have left them uniquely prepared, almost compelled, to accept new ideas and to make changes in their culture and ideology. The Jesuits were among the groups that influenced them. Other Amerind groups living around the Miamis certainly influenced them, as did the French traders, but both of these groups offered models for change more in the material realm than the ideological — they offered ideas on how to get along better in the wilds of Wisconsin, not how to alter their view of the world. The Jesuits, on the other hand, were advocates of change on the ideological level, and their model was one that was remarkably well suited to the Green Bay Miamis.

Allouez and André, like all the Jesuit missionaries, had been trained in the spiritual doctrine of St. Ignatius of Loyola. St. Ignatius was a mystic, that is, he was able to communicate directly with God. The Jesuit order, which St. Ignatius founded, was therefore a mystical organization dedicated to the promotion of individual spiritual experience. [16] Prayer was of primary importance to the Jesuits, for it was seen by them to be the only way to communicate directly with God. Discovering, understanding, and carrying out God's will was the personal goal of every Jesuit. God's will, of course, was different for each human soul, so its discovery and commitment had to be a unique and personal venture. It was this message of individual spiritualism that the Jesuits attempted to impart on the Miamis — a personal spiritual experience in which each Miami could discover and carry out God's will for themselves.

For anyone with a knowledge of Algonquian religious belief the message the Jesuits were sending seems only slightly removed from the beliefs of the Miamis themselves. Miami religion was centered around an individual's attempts to communicate with supernatural power, known as manitou, through the act of blackening one's face with ashes, retreating to a secluded spot, and fasting. As explained by Allouez in 1671:

They pass four or five days without eating, in order that . . . they may see in their dreams some of those Divinities on whom, they think, depends all their welfare; and, as they believe that they cannot be successful in hunting the Stag or the Bear, unless they have first seen these in a dream, their whole anxiety is, before going to seek these animals, to see in their sleep the animal upon which they have designs. [17]

Fasting was performed by the Miamis before hunting and war, in order to gain the favor of a manitou and therefore gain the power to be successful in their venture. A young man's first fast, however, was special. The manitou whom he contacted then would remain with him for life, becoming a sort of guardian spirit. [18]

These beliefs, focused on individual spiritual experience, do not seem so very different from those of the Jesuits, and it is not difficult to see how they might be quickly understood and adopted by the Miamis. Their ability to comprehend and accept these ideas, however, must have been greatly facilitated by the way the Jesuits presented them. Allouez and André realized that they could not teach the Miamis how to have a personal spiritual experience in a setting that the Miamis did not understand — they knew that the Miamis could only come to understand God if they were allowed to interpret God through their own culture. Adapting themselves and their teachings to Miami culture, and letting the Miamis interpret those teachings in their own way was the basis of Allouez's and Andrés missionary practice.

Allouez and André, first of all, moved into the Miami culture. The Jesuit superior of New France, writing of Allouez in 1668 explained that "One must make himself...a Savage with these Savages, and lead a Savage's life with them." [19] This is precisely what Allouez and André did with the Miami. They lived with the Green Bay Miamis, in their own cabins, sharing their food, indeed completely dependent on the Miamis for everything.

Allouez and André, as well, fest free to adapt aspects of native culture that could facilitate the Amerinds' understanding of God. Perhaps the most striking example of this adaptation comes from André working among the Menominee. Upon entering a village André found a decorated pole from which hung a picture of the sun. The pole was meant as a sacrifice to the sun "to entreat it to have pity on them" and allow them to catch fish. André explained to the villagers that the sun could not help them, but that God could, and replaced the picture of the sun with his cricifix. André wrote that "On the following morning, sturgeon entered the river in such great abundance that these poor people were delighted, and all said to me . . . 'teach us to pray, so that we may never feel hunger'." [20] André's success in this village would perhaps never have occurred if he were not willing to use the people's own beliefs to promote Christianity — if he were not willing to adapt the native sacrificial pole to a Christian purpose.

The history of Miami and Jesuit relations, then, is not a history of conversion, but a history of accommodation. Allouez and André were out to give the Miamis a personal knowledge of God, and realized that Christian principles could only be learned by the Miamis in a way that fit within Miami culture, and so they implored the Miamis to adapt Christianity to Miami culture and Miami experience. Indeed, the promotion of syncretism was a goal of the entire Jesuit mission in North America. Robert Burns, writing of Jesuit missionaries in the Oregon country during the 19th century, explains this concept clearly:

The Jesuits who came to the Oregon country brought something more than the organization, resources, experience, and distinctive spirit of their Order. They brought as well an unusual missionary tradition. It was rooted in the principle of accommodation, of assimilating one's life to one's immediate environment, so as to influence not only individuals but the environment itself. The Jesuit was to adopt the language and manner of life of the country to which he moved. His rule had built-in mechanisms for change and exception, for mobility and experimentation. [21]

In the case I have looked at, the relationship between the Green Bay Miamis and two Jesuit missionaries between 1669 and 1679, it appears that because of the environmental and economic forces acting upon them, the Miamis were placed in a unique position to accept cultural change. The changes that came about from their intercourse with Allouez and André, however, appear not to be simply the product of the Jesuits' missionization, but rather the product of both the forces acting upon them to promote change, and the message being presented by the Jesuits. Allouez and André did not simply move in and convert the Green Bay Miamis, but fostered their process of cultural change, and I believe this is precisely what they wanted to do. I do not believe that Allouez and André were out to manipulate Miami culture, but rather to accommodate Christianity to Miami culture and experience. The Miamis, in turn (and because of a unique series of events that shook the foundation of their ideology), seem to have been prepared to accommodate the Jesuits and their desire to convey Christian principles.

Regardless of my interpretation, it is clear to me that the history of Miami and Jesuit relations is not a simple, one-sided affair, and I believe that relationships between native peoples and their Jesuit missionaries were not as simple and directional as they are often made out to be. The idea that the Jesuits were actively seeking syncretism between their beliefs and those of the Amerinds rather than absolute conversion seems often to be left out of discussions of these relationships. I believe it is time to re-think and re-examine the relations between native Americans and the Jesuits who lived and worked among them. For years, research was done under the false belief that the Jesuits were out to make French Catholics of the Amerinds, and as I have tried to show here, I believe they were not. The relations between Jesuits and Amerind groups need to be looked at in the light of Jesuit culture, Jesuit experience and training, and Jesuit missionary principles in order to gain a more enlightened picture of these first contacts on the American frontier.

NOTES

1Reuben Thwaites, The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, 73 volumes, (Cleveland, 1896-1901), 55:223.

2This research was brought together in my Master's Thesis, Miami-Jesuit Reltaions at Green Bay 1669-1679: A Study in Acculturation, (Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Purdue University, 1987).

3Charles Callender, "Miami," in B. Trigger, ed., Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15, Northeast. (Washington, D.C., 1978).

4Thwaites, Jesuit Relations, 44:247.

5Ibid., 55:207-209, 215.

6Charles Faulkner, "The late prehistoric occupation of northwestern Indiana," Indiana Historical Society Prehistory Research Series 5(1), (1972), 175-180.

7Charles Callender, "Hopewell archaeology and American ethnology" In D. Brose and N. Greber, eds., Hopewell Archaeology, (Kent, OH, 1972).

8Louise Kellogg, The French Regime in Wisconsin and the Northwest, (Madison, 1925), 99; see also Thwaites, Jesuit Relations, 55:201.

9Thwaites, Jesuit Relations, 58:63.

10Homer Barnett, Innovation, the Basis of Cultural Change, (New York, 1953), 87.

11Ibid., 87. Similar ideas are presented in Eric Wolf, Peasants, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1966), 77ff.; and in Melville Heskovits, Man and His Works, (New York, 1948), 448, 539. See also Peregrine, Miami-Jesuit Relations, 9-11.

12For example, Thwaites, Jesuit Relations, 58:63.

13A good discussion of Miami economy can be found in Vernon Kinietz, Indians of the Western Great Lakes, 1615-1760, (Ann Arbor, 1965), 170-179.

14Maurice Cornforth, The Theory of Knowledge, (New York, 1955), 70.

15This theoretical framework is obviously Marxist, and is somewhat simplistic. For the purpose this paper, however, it serves well, and brings to the forefront the idea that many diverse elements of society, economy, and environment were forces behind the Green Bay Miamis; acceptance of the Jesuits and their subsequent cultural change. It also highlights the fact, to be discussed later in this paper, that the Miamis' acceptance of the Jesuits was a dialectical process, and was not at all a one-sided affair. For a fuller discussion of these ideas, and a more complete theoretical framework, see Peregrine, Miami-Jesuit Relations.

16For a discussion of Jesuit belief and practice see René Fulop-Miller The Jesuits, (New York, 1963), 3-27.

17Thwaites, Jesuit Relations. 56:129.

18For a fuller discussion of Miami religious beliefs see Kinietz, Indians of the Western Great Lakes, 211-214.

19Thwaites, Jesuit Relations, 51:259.

20Ibid., 58:273-75.

21Robert Burns, The Jesuits and the Indian Wars of the Northwest, (New Haven, 1966), 38. See also James T. Moore, Indian and Jesuit: A Seventeenth-Century Encounter, (Chicago, 1982).

22See Bruce Trigger, Native and Newcomers, (Montreal, 1985), 168-169.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1985-1986/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 23-Mar-2011