|

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

Selected Papers From The 1991 And 1992 George Rogers Clark Trans-Appalachian Frontier History Conferences |

|

FORT JEFFERSON, 1780-1781: A SUMMARY OF ITS HISTORY

Kenneth C. Carstens

Murray State University, Kentucky

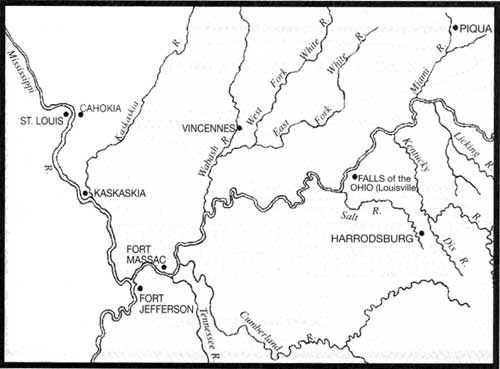

The origin of George Rogers Clark's Fort Jefferson dates from the summer of 1777 when Clark first developed his plans to capture the British posts of Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in the Illinois country. By June of that year, Clark had received word from his spies that the Illinois country could be taken easily. Clark formulated plans that included constructing a fort near the mouth of the Ohio River to facilitate trade with the Spanish and French settlements. A fort located at the mouth of the Ohio also would support, through possession, Virginia' s revised (1763) "paper claim" to her western boundary. By January, 1778, Clark received permission from Virginia Governor Patrick Henry to proceed with his secret operation (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Eighteenth century settlements and forts of the lower Ohio Valley (illustrated by Richard Mjos). |

Without firing a shot, Clark captured Kaskaskia, the first of two British-allied posts, on July 4, 1778. Even more remarkable was his success in approaching that community completely undetected. Clark and his small force, approximately 175 members of the Illinois Battalion, had traversed the entirety of the Ohio River from Fort Pitt to the mouth of the Tennessee River and had traveled overland from the Tennessee River to Kaskaskia on the Mississippi River.

To counter Clark's ambitious move westward, British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton brought his forces south from Detroit to take control of the garrison called Fort Sackville in Vincennes. Arriving at Fort Sackville late in the year of 1778, Hamilton decided to wait out the winter there along the Wabash River before attacking Clark at Kaskaskia Clark, however, seized the initiative.

Clark and his followers, accompanied by newly allied Frenchmen, left Kaskaskia during February, 1779, and headed northeasterly toward Vincennes. This move by Clark was planned both to surprise the British garrison at Vincennes by bringing the fight to them as well as to catch the British off guard and without their usual complement of Indian allies.

Clark's strategy worked. Hamilton and his forces surrendered Fort Sackville after approximately two days of half-hearted defense. The Americans, jubilant with their three victories, renamed the Vincennes fort, Fort Patrick Henry, to pay homage to the Virginia governor who initially had backed the enterprise.

Everybody loves a winner and George Rogers Clark was a winner. Between March and November, 1779, Clark's Illinois Battalion grew steadily as word of his undertaking reached the frontier settlements. Recruitment for the Illinois Battalion improved as a result of Clark's battlefield successes.

In November, 1779, Clark called a council of war with his junior officers to discuss the final part of his enterprising campaign — the building of a fort and of a civilian community near the mouth of the Ohio River.

During January, 1780, the new governor of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson, wrote letters to Joseph Martin, Indian agent; Daniel Smith, surveyor for Virginia; Thomas Walker, surveyor for Virginia; and George Rogers Clark. He directed Martin to contact the Cherokee to purchase land for the new fort. Jefferson did not know at the time, that rather than the Cherokee, it was the Chickasaw — a British ally — who claimed the area upon which the fort would be constructed.

Jefferson further instructed Daniel Smith and Thomas Walker to meet Clark at the site and to determine precisely the exact location, or latitude, of Clark's new fort, making sure it fell within Virginian territory and not upon North Carolina's land. In his communication to Clark, Jefferson gave permission to build the fort and an adjacent civilian community. The latter, Jefferson wrote, could be used to support the fort by growing food supplies Virginia could not afford to send. A civilian community also would attract young men whom Clark actively could recruit.

Clark and Robert Todd, the brother of John Todd and acting paymaster of the Illinois country, discussed the feasibility of reducing the garrisons in the Illinois country and of concentrating their populations at and around the new fort. Some resettlement did occur, but Kentucky County, the westernmost Virginian county in 1780, was about to see its single largest influx of settlers, more than 10,000 during a single year. By midyear, reshuffling of the Illinois population no longer seemed necessary.

To obtain settlers for the community and additional soldiers for his army, Virginia authorized Clark to grant 300 land warrants, each worth 560 acres, to every new soldier. By April, 1780, only a few additional supplies were needed before Clark could leave the Falls of the Ohio (present-day Louisville) for the new post. So promising were the prospects of the new settlement and garrison, that William Shannon, Clark's commissary at the Falls, requested six-months' provisions for 1,000 men.

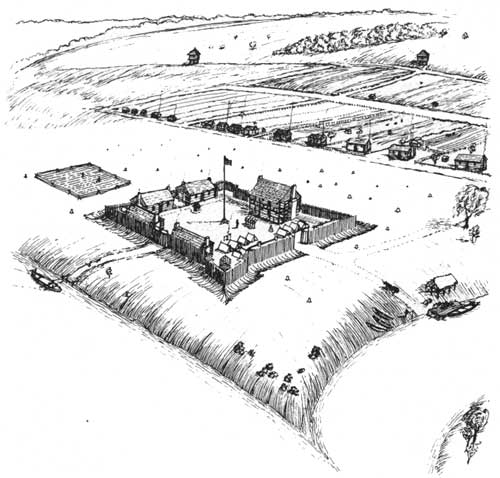

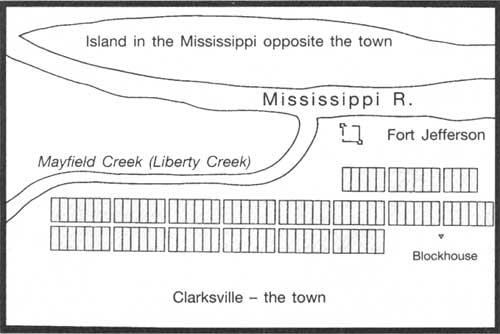

Clark, 175 soldiers and an untold number of civilians arrived April 19, 1780, at the spot selected for the new settlement. In honor of the presiding Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson, Clark called the new post Fort Jefferson. The adjacent civilian community became known as Clarksville, also Clark's Town. The fort and community were on a slightly elevated floodplain between Mayfield Creek, also then called Liberty Creek, and a series of eroded bluffs located to the north. The main stream of the Mississippi River was then about one-half mile west of the fort (Figure 2). Clark's men and the settlers set to the task at hand, clearing the woods and constructing the outpost and town. Clark, however, would have little further time to invest with the fort or settlement.

|

| Figure 2: A redrafted version of the 1780 William Clark map of Fort Jefferson and the town of Clarksville (illustrated by Richard Mjos). |

Jefferson, writing from Williamsburg, suggested Clark should lead a force into the Shawnee country to counter the Indians' attacks on the central Kentucky settlements. Jefferson did not realize that a more pressing issue was developing near Clark's new post. Word arrived at Fort Jefferson that a strong force of Indians and British soldiers was expected to attack both St. Louis (also referred to as Pancore) as well as Cahokia. Taking all but 18 regulars from Fort Jefferson, and leaving Captain Robert George in charge of the new post, Clark proceeded north to Cahokia, arriving May 24, two days before the Battle of St. Louis. Clark and the united French, Spanish, and American forces promptly defeated the British and Indian raiders.

Meanwhile, word reached Fort Jefferson from O'Post (Fort Patrick Henry in Vincennes) that British attacks on the central Kentucky settlements were expected any day. News also was received that the Spanish planned to attack the British strongholds at Mobile and Pensacola, actions which would help free the trade on the Mississippi.

By June 1, Clark's triumphant Illinois Battalion began to relocate at Fort Jefferson. On June 4, 1780, Captain Robert George, Fort Jefferson's commandant, advised Clark that the construction of the new post was nearing completion. Captain George hoped to have the garrison enclosed with pickets by the end of that week and the settlers, George wrote, nearly were finished with their planting.

The fort was enclosed none too soon. By June 7, marauding Chickasaw began killing members of the Clarksville militia who were surprised on the outskirts of the town. Although it had not been a full-scale attack, the Indians' presence was a considerable menace to the fort and settlement.

By June 10, Clark had returned to Fort Jefferson with his soldiers and the Indian problem faded into the background. A more demanding obstacle redirected Clark's attention.

An express messenger from the Falls of the Ohio brought word of an increased number of hostile Indian attacks in the central Kentucky area. Colonel Daniel Brodhead at Fort Pitt preferred not to deal with the problem, recommending, instead, that Clark attack the Shawnee "from his quarter."

On June 10, 1780, Clark and two others left Fort Jefferson for the Falls of the Ohio. Between June 10 and 14, considerable issues of goods and clothing were made at Fort Jefferson to outfit Clark's army for the Shawnee campaign. By mid-June, half of the Fort Jefferson troops had left their post to meet Clark at the mouth of the Licking River (across from present-day Cincinnati) to launch the expedition. Clark had begun recruiting for the operation as soon as he had reached the Falls.

The civilian community at Fort Jefferson continued to grow and to prosper. On June 13, several Clarksville trustees (James Piggott, Ezekiel Johnson, Henry Smith, Joseph Hunter, and Mark Iles) wrote to the Virginia government to have Clarksville and its surrounding area recognized as a new county, which, if approved, would give the county a vote in the Virginia legislature. Their petition was sent along with those troops leaving Fort Jefferson June 14, 1780, on their way to join Clark's Shawnee expedition.

For the next two weeks, all went well at the post on the Mississippi. Numerous issues for dry goods, to be made into soldiers' clothing, were sewn for officers and enlistees alike. The fort's bartering system was well established, as witnessed by the type and kind of payments received by the tailors and seamstresses who made clothing for the soldiers. A company of Virginia light dragoons (cavalry) commanded by Captain John Rogers, a maternal cousin of George Rogers Clark, was newly outfitted and was Provisioned at Fort Jefferson. On July 14, 1780, they departed for Cahokia and Lieutenant Colonel John Montgomery left for Fort Clark at Kaskaskia.

Three days later at daybreak, the Chickasaw again attacked the Clarksville community, killing two of the militia and wounding several others. The fight, however, was brief and led to relatively little destruction. The shooting was more of a test by the Chickasaw to determine the military strength of both the fort and the community. After obtaining the information they needed, the Indians withdrew.

By July 20, 1780, Laurence Keenan and Joshua Archer were, sent as expresses to Fort Clark where they sought the assistance of Lieutenant Colonel Montgomery. Sixty-five Kaskaskia Indians and 10 members of Captain Richard McCarty's company arrived from Fort Clark to assist Fort Jefferson on July 31, 1780. The Indian allies were employed primarily by Captain George to hunt for the garrison. Also arriving from Fort Clark at Kaskaskia was Captain John Bailey and William Clark (paternal cousin to George Rogers Clark, not George's younger brother). Bailey and William Clark brought with them 1,400 pounds of flour, 50 bushels of corn, and 28 men from Bailey's company of infantry.

Members of the fort and of the community entered August, pleased that they successfully had thwarted two attacks by the Chickasaw. Undoubtedly they also were proud that they had helped to defeat the combined Anglo-Indian assault on St. Louis and Cahokia the preceding May. Recent arrivals at Fort Jefferson, Captain Richard McCarty and his military company along with Timothe B. Monbreun, added to the feeling of security at the post. But it now was understood that an attack by the Chickasaw might occur at any time and might come from any quarter. Therefore, a higher status of alert was ordered and arms and munitions were issued to the troops to maintain a "prepared" normalcy.

On the morning of August 27, 1780, the civilians and the soldiers of Fort Jefferson once again were tested by the Chickasaw. This time, however, a great band of Chickasaw attacked the community and its garrison. Estimates of their number varied. The most conservative figure came from Captain George, who suggested that 150 Chickasaw had assailed the post. In this encounter, the Chickasaw were led by Lieutenant William Whitehead, a member of the British Southern Indian Department, and by James Colbert, a Chickasaw half-breed "Big Man."

Halfway through the battle, Colbert appeared with a flag of truce and demanded the surrender of the post to prevent additional bloodshed. Captain Leonard Helm, Captain George's second-in-command, told Colbert the Americans would not surrender. Wheeling to walk away from the parley, Colbert was shot in the back by a Kaskaskia Indian. Fighting recommenced later that evening. At the end of the fourth day of battle, August 30, the Chickasaw retreated, but not before they had destroyed much of the corn crop and had killed many of the settlers' cattle and sheep. In addition to these losses, several Negro slaves had been shot by the Chickasaw and a number of the militia either were wounded severely or had lost their lives during the battle. Captain John Bailey's company had been ambushed by the Chickasaw while on a hunting party. Four members of his troop were killed and a fifth had been taken prisoner. Nevertheless, the state of preparedness during early August probably saved many more lives at the post.

September was a depressing time for the inhabitants and soldiers of Fort Jefferson. With much of the corn crop destroyed, there was little, if any, hope for food during the forthcoming months. The few bushels of corn that could be garnered from the devastated fields barely would feed the garrison, let alone the town's men, women, and children. Fearful of spending a winter with little or no food, 24 of the town's 40 families moved between September 12 and 14, electing to go down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, up the Mississippi to Kaskaskia, or up the Ohio River to the Falls area. To make matters worse, there also were many desertions from Clark's Illinois Battalion. Although there then were fewer mouths to feed at Fort Jefferson, there also were fewer inhabitants and soldiers to defend the post or to assist with the continued construction of the new town.

September marked the beginning of the "sickly" season, as Captain George called it. An examination of the September vouchers vividly illustrates that many persons, soldiers and civilians alike, became sick with the ague (flu) or began suffering from the effects of malaria. As a result, the garrison and town had fewer people than before and those who remained generally were too ill to move: or to desert their posts.

Not all was gloomy, however. On September 6, a load of supplies arrived by boat from New Orleans; part of the cargo included 1,200 pounds of gunpowder. On September 10, a party of Kaskaskia Indian allies was granted permission by Captain Georgee to seek revenge against the Chickasaw for the recent hostilities.

October was not much of an improvement from September. Between the fourth and fifth, four more persons were killed near the fort. Although additional ammunition was issued to the post and town, the Indians never fully showed themselves, keeping just outside the community where they could harass the settlers and soldiers. Sickness continued to prevail as did further desertions.

Physical problems now were accompanied by political intrigue. Lieutenant Colonel John Montgomery arrived with Captain John Williams from Kaskaskia on October 22. Lieutenant Colonel Montgomery wanted Captain George to relinquish his command to Captain Williams. George refused, subsequently writing to Colonel Clark to explain that he would not forego his command unless ordered to do so by Clark. Williams, obviously caught in an awkward situation, also wrote to Clark, stating that he would not take command until he received orders from Clark. Although Montgomery and George did not get along, Montgomery did assist George in his efforts to save the post. By October 28, Montgomery had left Fort Jefferson for New Orleans to procure additional supplies for the garrison and community. Writing later that day, Captain George observed that Fort Jefferson had been reduced severely by famine, desertion, and death. Now, during near drought conditions, low water in the Mississippi hampered efforts to get supplies to the fort.

Montgomery's assistance in New Orleans paid off when a shipment of new supplies arrived in November. Even so, soldiers and civilians spent most of their time, when not too ill, making nets in order to seine for fish in the shallows of the Mississippi River. The American frontiersmen experienced a relatively better month during December, 1780. In his letter to George Rogers Clark during the first few days of December, John Donne, the fort's deputy commissary, reported that militia Major Silas Harlan and other hunters had been successful in bringing more than 8,000 pounds of buffalo, bear, and deer meat into the fort. Unfortunately, there still were more than 150 persons in the garrison, 20 civilian families who had to be fed, and the expectation that several new military companies might arrive any day. Food, although now available, still was in short supply.

On the 12th of December, and again on the 15th, cargo supplies arrived from New Orleans and from the Falls of the Ohio. Both shipments included primarily munitions and dry goods. While these loads contained new shoes, which were welcomed, the newly arrived dry goods would have to be used as barter for food in Kaskaskia and in other Illinois towns. In spite of a bleak outlook, Christmas was greeted by Captain George's company of artillery by expending 60 pounds of gunpowder in salutes fired from Fort Jefferson's five swivels and two cannon.

Within a few days another shipment from New Orleans was delivered by Captain Philip Barbour on behalf of Oliver Pollock, American agent in New Orleans. Barbour, seeing the depressed condition of the fort and civilian community, negotiated the sale of his $25,000 cargo to $237,320. Not wanting to lose the supplies, Captain George conferred with his fellow officers and then agreed to meet Captain Barbour's demand. The cargo, consisting primarily of dry goods and tafia (watered-down rum), immediately was put to use.

In high spirits, the community and soldiers raised their cups to what appeared to be a bright and shiny new year. Supplies were unloaded, repacked, and sent to Kaskaskia and to the Falls in order to procure foodstuffs for the garrison and civilian community.

Another part of the shipment included munitions. Nearly every member of the garrison, including militia and Indians, received a sword and Clark's Illinois Battalion officers obtained their new clothing allotments for the year. In addition, the Kaskaskia Indians were granted permission once again to attack the Chickasaw.

January revealed the growing dislike shared by the fort's officers and civilians for Captain John Dodge, Indian agent and quartermaster for the Illinois Department. Although Dodge would have but a few months left at Fort Jefferson (he spent the first part of the spring at Kaskaskia, then left to settle his books at Richmond), the majority of the inhabitants felt cheated by his dealings and he proved to be a constant source of friction with the officers.

On January 23, 1781, another boatload of supplies was received at Fort Jefferson. A tafia ration (one gill each) for January 30 showed that 110 men remained in the garrison. Captain John Bailey, and his company of infantry had departed for O'Post (Vincennes) earlier that month.

February and March of the new year witnessed several activities that would dominate post functions for the next several months. Fort Jefferson became the hub for the distribution of arms, munitions, dry goods, and liquor as military companies arrived from other Illinois outposts and companies from Fort Jefferson delivered supplies to them. Fort Jefferson finally was becoming Clark's economic center and military stronghold along the Mississippi.

Fort Jefferson's prosperity began to erode, however, as quickly as it had been achieved. Although the post then had more dry goods, munitions, and rum (and whiskey) than it possibly could use, its larder still was quite empty in spite of daily hunting parties comprised of soldiers and Indians. No matter how much tafia was consumed (and incredible amounts were), daily meals consisted of little solid food. Grumbling and discontent with the post's conditions were no longer restricted to whispers among friends. Serious charges were made which only could be settled through courts of inquiry.

During March, courts of inquiry were convened to examine the conduct and character of two of the fort's newly arrived officers, Captains Edward Worthington and Richard McCarty. Worthington, who had postponed for months his trip from the Falls to Fort Jefferson, was accused of retailing liquor, gambling with the soldiery, and frequently disobeying orders. McCarty, on the other hand, was charged with threatening to leave the service (as well as Virginia) and with insulting a fellow officer. The outcome of Worthington's court of inquiry is unknown. McCarty was found guilty and a general court-martial was recommended. His chief accuser was John Dodge. McCarty never would suffer the embarrassment of a court-martial, however. Two months later, while en route to the Falls, he was killed by Indians.

Near the end of March, a third court of inquiry was scheduled in the public store at Fort Jefferson. The session examined the conduct of Captain John Rogers, who had been in command at Fort Clark in Kaskaskia. These charges had been brought by Dodge again, but this time the court found them to be without substance and acquitted Rogers.

March was a "happy" month for the majority of the Irish-American officers and soldiers. Their consumption of large quantities of tafia and whiskey truly was amazing, as were their excuses for imbibing the libations. Whether drinking to Saint Patrick's health or death, or maybe even toasting Saint Patrick's wife, Shealy, the Fort Jefferson community members properly celebrated their ethnic customs.

On the other side of the coin, however, there existed discontent and boredom. Lieutenant John Girault, for example, pleaded in a letter to George Rogers Clark that he might be sent on an expedition or otherwise employed usefully somewhere, implying that nothing of consequence was occurring at Fort Jefferson. As tensions relaxed, so did discipline. James Taylor and David Allen were court-martialed on charges of speaking disrespectfully to an officer beating an officer's servants, and robbing an officer's kitchen. Taylor was acquitted, but Allen was found guilty and received 50 lashes on his bare back.

April brought heavy rains which, in turn, raised water levels dangerously high in nearby Mayfield Creek and the Mississippi River. As a result, by April 25, 1781, many items in the public store had to be removed to higher ground by the fort's soldiers.

Several letters were received in April from General George Rogers Clark. (Clark's promotion from colonel to general had occurred during January, 1781.) The content of those letters is unknown, but as Clark had received permission to plan an assault against Fort Detroit, it is possible that these letters focused on Detroit and that Clark suggested to his officers that they begin preparing for the evacuation of Fort Jefferson.

By the 10th of May, Lieutenant Colonel Montgomery had returned to Fort Jefferson. Shortly after his arrival, increased unhappiness at the post led one of the militia men to attempt a break-in at the fort's public store, forcing Captain George to call for an inspection of the town.

Evidence of decline was all too apparent. By the first of May, the number of men remaining in the garrison was down to 58. It is evident that the decision to evacuate Fort Jefferson was made prior to June 5, 1781. On that date Captain Abraham Keller's company left the fort for the Falls area. The remaining soldiers and civilians departed June 8, 1781, the official date of evacuation. Numerous goods, far too cumbersome to remove, were left at the old fort, as were the earthly remains of at least 38 men, women, and children who were buried in the post's cemetery.

The fort, occupied for only 416 days, had served its function. The fort's presence, though short-lived, on Virginia's western boundary (as well as the Virginian military occupations of Kaskaskia and of Vincennes) provided the physical evidence the state needed to justify its claim to its chartered boundaries. On July 12, 1781, tired and exhausted, the Fort Jefferson survivors arrived at General Clark's new stronghold, Fort Nelson, located at the Falls of the Ohio. Thus ended the saga of George Rogers Clark's Fort Jefferson.

REFERENCES

Draper, Lyman C.

n.d. The Draper Manuscripts. State Historical Society

of Wisconsin, Madison.

Harding, Margery Heberling

1981 George Rogers Clark and His Men: Military

Records, 1778-1784. The Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort

Henry, Patrick

1777 Letter to Governor Bernardo de Galvez. Archivo

General de Indias Seville, Estante 87, Cajon 1, legajo 6, Spain.

James, James Alton, ed.

1972 George Rogers Clark Papers, 1771-1784.

Vols. I and II. Reprinted AMS Press, New York.

Jameson, Ann McMeans

n.d. The Personal Narrative of Ann McMeans Jameson.

Unpublished manuscript. The Filson Club, Louisville.

McDermott, John Francis

1980 The Battle of St. Louis, 26 May 1780.

Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis.

Missouri Historical Society

n.d. The William Clark Papers. The Missouri

Historical Society, Forest Park, St. Louis.

Seineke, Kathrine Wagner

1981 The George Rogers Clark Adventure in the

Illinois and Selected Documents of the American Revolution at the

Frontier Posts. Polyanthos, New Orleans.

Sioussat, St. George L.

1915 The Journal of General Daniel Smith, one of the

commissioners to Extend the Boundary Line between the Commonwealths of

Virginia and North Carolina, August, 1779, to July, 1780. The

Tennessee Historical Magazine, 1(1): 40-65, Nashville.

Virginia State Library

n.d. The unpublished papers of George Rogers Clark.

Virginia State Library, Archives Division, Boxes 1-50, Richmond.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1991-1992/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 23-Mar-2011