|

SHILOH National Military Park |

|

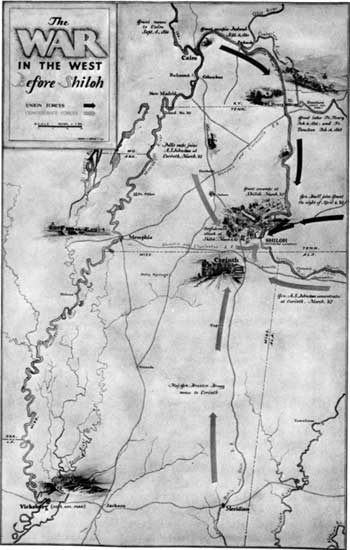

Preliminary Campaign

War activity west of the Appalachian Mountains in 1861 was confined chiefly to the States of Kentucky and Missouri. Toward the end of the year when loyalty, or at least the neutrality, of the governments of these border States seemed assured, the Federals began making plans for the invasion of the South by way of the western rivers and railroads. Each side began to maneuver for strategic positions. The Confederate General, Leonidas Polk, believing that the Southern States were about to be invaded through Kentucky, moved up quickly from his position at Union City, Tenn., and seized Columbus, Ky., the northern terminus of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, recently appointed commander of the Federal troops in and around Cairo, Ill., had made preparations to occupy that important river port and railway center on the following day. Thwarted at Columbus, Grant retaliated by taking Paducah, Ky., located at the junction of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers.

It now became apparent to the Confederate high command in Richmond that a strong line would have to be established along the northwestern border of the Confederacy before the Union armies had time to occupy more of the strategic points. They believed that the task could be performed more effectively if all troops in that theater of operation were placed under one commander. Accordingly, Confederate President Jefferson Davis sent Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston to the West with the imposing title of "General Commanding the Western Department of the Army of the Confederate States of America."

Commodore Foote's gunboats ascending the Tennessee to attack Fort

Henry.

Arriving in Nashville on September 14, 1861, General Johnston studied his difficult assignment. The line he was supposed to occupy extended from the mountains of eastern Tennessee westward across the Mississippi to the Kansas boundary. Only two points on the proposed line were then in Confederate hands: Columbus, which he considered the natural key to the Confederate defense of the Mississippi, and Cumberland Gap, Ky., which he had previously ordered Gen. Felix K. Zollicoffer to occupy.

One of Johnston's first official acts upon arriving at Nashville was to order Gen. Simon B. Buckner to secure Bowling Green, Ky., one of the most important railroad centers south of the Ohio. He also ordered garrisons to the incomplete works at Fort Henry, on the Tennessee, and Fort Donelson, on the Cumberland, hoping to prevent a Union advance up either of these natural highways. A Federal offensive up the Tennessee or the Cumberland would endanger the important railroad and industrial center of Nashville, Tenn.

Since the outbreak of the war, Nashville had been converted into a huge arsenal and depot of supplies. Large quantities of food, clothing, and munitions had been collected and stored in its warehouses. Its factories were turning out percussion caps, sabers, muskets, saddles, harness knapsacks, cannon, and rifled pieces. Its looms were turning out thousands of yards of gray cloth which were being made into uniforms for the soldiers. The loss of this city would be an irreparable blow to the Confederacy.

Dover Tavern, General Buckner's headquarters and scene of the surrender

of Fort Donelson.

While General Johnston was establishing his positions, the Federals were rapidly organizing their forces preparatory to an attack upon the Confederate line. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, from headquarters in St. Louis, was strengthening his positions at Cairo, Ill., and Paducah, Ky. At the same time, he was making ready a large number of river steamers so that his troops could be moved by water to almost any point along his front. From headquarters in Louisville, Gen. Don Carlos Buell, commander of the Department of the Ohio, reinforced his line so that Johnston had to keep his main force at Bowling Green, Ky., to guard the important railroads which penetrated Middle and West Tennessee.

Various plans for an attack upon the Confederate line were considered by the Federals. General Halleck, commander of the Department of the Missouri, believed that it would take an army of not less than 60,000 men, under one commander, to break the well-established line. He, therefore, asked that General Buell's army be transferred to him, or at least placed under his command.

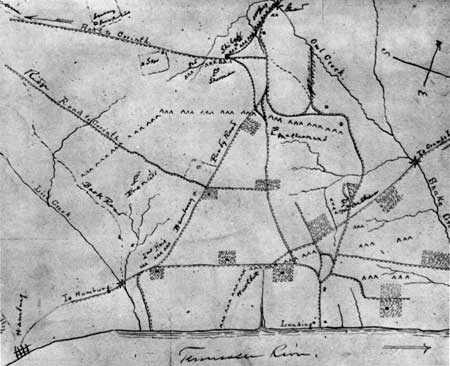

Map of the battlefield of Shiloh, made

by Gen. W.T. Sherman soon after the battle.

Before a union of the two departments could be effected, General Grant asked for, and received, permission to attack the line at Fort Henry. A combined land and naval attack by Grant's troops and the gunboat fleet of Commodore Andrew H. Foote resulted in the surrender of Fort Henry on February 6, 1862, and the capture of Fort Donelson, with about 12,000 prisoners, on the 16th. The loss of these forts broke Johnston's line at its center and compelled him to evacuate Bowling Green and Columbus, permitting western Kentucky to fall into Union hands. To prevent encirclement, he was also forced to withdraw from Nashville, abandon Middle and West Tennessee, and seek a new line on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad.

Following the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson, Grant incurred the displeasure of General Halleck by sending a division of troops into Buell's department at Clarksville. Halleck's indignation increased when he learned that Grant had gone to Nashville for consultation with Buell. Halleck directed the withdrawal of the division from Clarksville suspended Grant from command, and ordered him to Fort Henry to await orders.

Conference of Confederate commanders the night

before the battle. From left to right, Gen. P. G. T Beauregard, Gen. Leonidas

Polk (seated), Gen. John C. Breckinridge, Gen. A. S. Johnston,

Gen. Braxton Bragg, and Maj. J. F. Gilmer. Gen. W. J.

Hardee was not present.

The army under Grant's successor, Gen. Charles F. Smith, moved up the Tennessee toward the heart of the Confederacy, with the intention of rendezvousing at Savannah, Tenn., on the east side of the river. Gen. William T. Sherman was sent forward on the so-called Yellow Creek Expedition for the purpose of destroying railroad communications to the west of Corinth, Miss., the objective of the campaign. High water made Sherman's mission a failure, and he was compelled to return. He reported to General Smith that a more convenient place for the assembling of his army was at Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., 9 miles above Savannah, and on the west side of the river, from which direct roads led to Corinth. General Smith, therefore, instructed him to disembark his division and that of Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut at Pittsburg Landing, in positions far enough back to afford room for the other divisions of the army to encamp near the river.

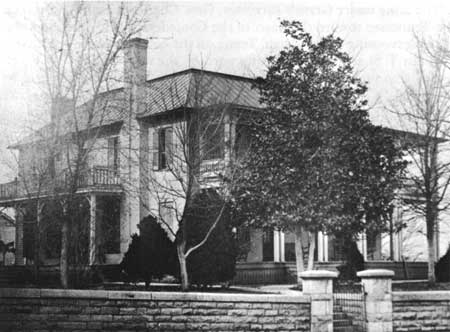

Cherry Mansion, Savannah, Tenn., used as

headquarters for the Union Army, March 13 to April 29, 1862. While

eating breakfast in this house, General Grant heard the sounds of heavy

firing which told him the battle had begun. Generals W. H. L. Wallace

and C. F. Smith died here in April 1862.

In obedience to this order, Sherman encamped his division along a ridge on either side of Shiloh Church, almost 3 miles from Pittsburg Landing, with General Hurlbut's division about a mile to his rear. Within a few days, Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss' division took position on Sherman's left, while Gen. John A. MeClernand and Gen. W. H. L. Wallace formed their divisions between Sherman and the river. The 3d Division, commanded by Gen. Lew Wallace, was stationed at Crump's Landing, about 4 miles downstream from the main encampment. Thus, by April 5, 1862, there were in the five divisions of the Army of the Tennessee at Pittsburg Landing 39,830 officers and men present for duty and 7,564 at nearby Crump's Landing.

While this concentration of troops was in progress, General Smith received a leg injury which became so serious that he had to give up his command. General Grant was restored to duty and sent to Savannah with orders to concentrate troops and supplies, but to bring on no general engagement until a union could be made with Buell's army, and Halleck had arrived to assume personal command of the combined forces.

General Johnston, in the meantime was concentrating all available forces at Corinth, Miss., on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. After this had been accomplished, he resolved to take the offensive and attack Grant's army at Pittsburg Landing, hoping to defeat that army before it could be reinforced by General Buell. Hearing that Buell was nearing Savannah, Johnston determined to attack at once and accordingly on the 3d of April issued the order for the forward movement. He expected to give battle at daylight on April 5th, but heavy rains and bad roads made progress so slow that the last of his columns did not reach the field until late afternoon. It was then decided that the attack should be postponed until daylight the next morning. Johnston's army, 43,968 strong, went into bivouac in order of battle within less than 2 miles of the Federal camps. The Confederate forces were formed in three lines. Gen. W. J. Hardee's corps and one of Gen. Braxton Bragg's brigades were in the first line, the remainder of Bragg's corps in the second line, and Generals Leonidas Polk's and J. C. Breckinridge's corps in the third line.

During the night of April 5th the two hostile armies were encamped within a short distance of each other: the Confederates poised, ready to attack, while the unsuspecting Union army went about its normal camp routine, making no preparations for the defense of its position. On Saturday, a few hours before the battle, Sherman wrote Grant: "I have no doubt that nothing will occur to-day more than some picket firing," and that he did not "apprehend anything like an attack" on his position. The same day, after Sherman's report from the front, Grant, who was at Savannah, telegraphed Halleck: "I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack (general one) being made upon us, but will be prepared should such a thing take place."

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |