|

SHILOH National Military Park |

|

The Confederate charge upon Prentiss' camps.

From "Battles and

Leaders of the Civil War."

The First Day

The battle began about 4:55 a. m., Sunday, April 6, when a reconnoitering party of Prentiss' Union division encountered Hardee's skirmish line, under Maj. Aaron B. Hardcastle, a short distance in front of Sherman's camps. The reconnoitering party—three companies of the 25th Missouri under Maj. James E. Powell—fighting and retreating slowly toward its camps was reinforced by four companies of the 16th Wisconsin and five companies of the 21st Missouri. These troops were, in turn, reinforced at the northeast corner of Rhea Field by all of Col. Everett Peabody's brigade. Here they succeeded in holding the Confederates in cheek until about 8 a. m., when they fell back to Prentiss' line of camps, closely followed by the enemy.

General Sherman, hearing the picket firing in his front, immediately got his division under arms and posted a battery at Shiloh Church and another on the ridge to the south. The left of this hastily formed line received the full impact of the Confederate onslaught at about the same time that Prentiss' camps were attacked. One of the regiments in the left brigade—the 53d Ohio—consisted of raw troops who had never been under fire. Unable to withstand the fierce Confederate attack, this regiment soon broke and fled to the rear. A short time later the other two regiments of the brigade did likewise. The commander of the brigade, Col. Jesse Hildebrand, refused to leave the field with his men. Since he had no troops of his own, he acted as aide for General Me Clernand the rest of the day.

Union defenders of the Hornets' Nest (right) repulsed 11 Confederate

charges against the Sunken Road.

General Prentiss, in the meantime, was making a gallant, but futile, stand along his line of camps. Assailed by the eager Confederates in front and on the flanks, his whole division soon broke and fell back in confusion. He succeeded in rallying about 1,000 of his men on the center of a line that W. H. L. Wallace and Hurlbut were forming with parts of their divisions in a strong position in the rear. This new line, running through a densely wooded area along an old sunken road, proved to be such a strong position that the Confederates named the place "Hornets' Nest" because of the stinging shot and shell they had to face there.

The Sunken Road near Bloody Pond.

Meanwhile, General Grant at breakfast in Savannah heard the guns in the battle of Shiloh. He at once sent word to the advance of Buell's army, which had already arrived at Savannah, to march immediately to the point on the river opposite the battlefield. He then hurried up the river aboard the steamer Tigress, moving in close enough to the shore at Crump's Landing to instruct Gen. Lew Wallace to be prepared to execute any order he might receive. Upon arriving at the field, he dispatched reinforcements to Prentiss and formed two regiments in line near Pittsburg Landing, to arrest the tide of stragglers from the battle and organize them to return. He then rode to the front.

While the Confederate right was engaged with Prentiss, the left, supported by continuous artillery fire, was hurled against the combined forces of Sherman and MeClernand who were making a stubborn stand along the ridge at Shiloh Church. This small log building, which gave its name to the battle, was considered the key position of the field, as it commanded the best road from Corinth to Pittsburg Landing. When General Grant reached the church, about 10 a. m., his troops were heavily engaged all along the line. They had resisted the relentless pounding from the Confederate artillery and the repeated infantry charges for over 2 hours. Seeing that the line could not hold much longer, Grant dispatched orders to Lew Wallace to move to the field, expecting him to reinforce the Union right. Leaving Sherman, he moved down the line to the left to confer with his other division commanders. He visited Prentiss in the Hornets' Nest and directed him to hold his position there at all hazards.

Johnston mortally wounded.

Soon after Grant's departure, Sherman withdrew from Shiloh Ridge, abandoning his camps and much of his equipment. He took a new position behind the Hamburg-Purdy Road alongside MeClernand who had been pushed back on line with Prentiss' Hornets' Nest position.

Grant's army was now posted on either side of Prentiss, making a line approximately 3-1/2 miles long. The opposing army was charging this line with a series of frontal attacks, just as hard on the left as on the right. This was contrary to Johnston's plan of battle. He had intended to push hardest on the Union left and seize their base of supplies at the Landing. Without supplies or an avenue of escape, he hoped to drive the disorganized Federals into the swamps of Snake and Owl Creeks and destroy them.

Seeing that the enemy was being driven into its base of supplies rather than away from it, Johnston, about noon, moved to the extreme right to direct in person the activities of that wing of his army. There, he found his troops exposed to a galling fire and unable to advance. Determined to move his line forward, Johnston ordered and led a successful charge. The Union lines recoiled, and the Confederates surged forward about three-fourths of a mile. As Johnston sat on his horse, watching the lines re-form, a ball from the gun of an unknown Union soldier struck the Southern commander, severing the large artery in his right leg. No surgeon being near, he died from loss of blood at 2:30 p.m.

The death of Johnston caused a lull in the battle on the right flank for about an hour. The situation was relieved somewhat by the fact that a second in command was on the field. Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard was in charge of headquarters which had been established near Shiloh Church. When informed of Johnston's death, he immediately assumed command. He sent General Bragg to the right of the field and put Gen. Daniel Ruggles in command at the center.

General Ruggles, having witnessed 11 unsuccessful charges against the Hornets' Nest, decided to concentrate artillery fire upon the position. Therefore, he collected all the artillery he could find—62 pieces—and opened fire upon the Union line. Under cover of continuous fire from these guns, the Confederates attacked with renewed courage and redoubled energy. Unable to withstand the assault, the troops on both the Federal right and left withdrew toward the Landing, leaving Prentiss and W. H. L. Wallace isolated in the Hornets' Nest. As the Union forces withdrew, the left of the Confederate line swung around and joined flanks with the troops moving around from the right, thus forming a circle of fire around Wallace and Prentiss.

Wallace, seeing that the other divisions were withdrawing and that his command was being surrounded, gave the order for his troops to fall back. To execute the order, his division had to pass through a ravine which was already under the crossfire of the encircling Confederates. Wallace was mortally wounded in the attempt, but two of his regiments succeeded in passing through the valley, between the Confederate lines which they appropriately named "Hell's Hollow." Prentiss continued the resistance until 5:30 p. m., when he was compelled to surrender with over 2,200 troops—all that remained of the two divisions.

During the afternoon, Col. Joseph D. Webster, Grant's Chief of Artillery, placed a battery of siege guns around the crest of a hill about a quarter of a mile in from the Landing. The smaller field artillery pieces were put in position on either side of them as they were moved back from the front. The two wooden gunboats, Tyler and Lexington, anchored opposite the mouth of Dill Branch, further strengthened the line. As the remnants of the shattered Union Army drifted back toward the Landing, they were rallied along this line of cannon.

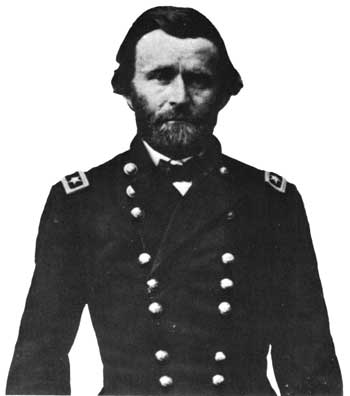

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

Courtesy National Archives.

After the capture of Prentiss, an attempt was made to reorganize the Confederates for an attack upon the Union position near the Landing. Before a coordinated attack could be made, Beauregard, who had received word that Buell would not arrive in time to save Grant's army, sent out the order from his headquarters at Shiloh Church to suspend the attack. Unknown to Beauregard, the advance of Buell's army had already arrived opposite Pittsburg Landing and was being rapidly ferried across the river.

During Sunday night and Monday morning, Buell moved approximately 17,000 troops into line on the Union left. Lew Wallace put almost 6,000 fresh troops—Fort Donelson veterans—in position on the right. The Confederates, receiving no reinforcements, spent a sleepless night in the captured Union camps annoyed by shells from the gun boats, which were thrown among them at 15-minute intervals through out the night.

Gen. Don Carlos Buell.

Courtesy National Archives.

The battle had already raged for 13 hours. Charge after charge had been made by the Confederates, followed by Federal countercharges. Ground had been gained and lost, but the general direction of movement had always been toward the Landing. By the time the day was over and the weary soldiers had lain down to rest, the Confederates were in possession of all the field, except the Landing and a bit of adjoining territory. Many Southern soldiers, in view of the gains made during the day, believed that the victory was already theirs. An equally large number of Northerners were willing to concede defeat. When night at last closed in around the hostile armies, feelings of uncertainty prevailed among the leaders on both sides. Many of them were well aware that the battle was yet to be won or lost.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |