|

YORKTOWN National Battlefield |

|

The reconstructed Grand French Battery—a

strong link in the First Allied Siege Line.

ON THE LEVEL FIELDS outside the small colonial village of York town occurred one of the great decisive battles of world history and one of the most momentous events in American history. Here, on October 19, 1781, after a prolonged siege, Lord Cornwallis surrendered his British Army to an allied French and American Army force under George Washington, virtually ending the American Revolution and assuring American independence. While hostilities did not formally end until 2 years later—on September 3, 1783, when the treaty was signed—in reality the dramatic victory at Yorktown had ended forever the subservience of the American colonies to England. Because of this victory the United States became truly a free and independent nation.

The Virginia Campaign

At Yorktown, in the early autumn of 1781, Gen. George Washington, ably assisted by the Count de Rochambeau of the French Army and supported by the Count de Grasse of the French Navy, forced the capitulation of Lieutenant General Earl Cornwallis. On October 19, the allied French and American forces accepted the surrender of the British troops in what was the climax of the last major British field operation of the American Revolution—the Virginia Campaign.

The early campaigns, except the decisive repulse of British arms in the Carolinas in 1776, were fought mostly in the New England and Middle Atlantic colonies. After 1778, most activity was to the south. In 1780 and early 1781, Lord Cornwallis led his victorious British Army out of Charleston and through the Carolinas; not, however, without feeling the effective use of American arms at Kings Mountain (October 7, 1780) and at Cowpens (January 17, 1781). On March 15, 1781, he was at Guilford Courthouse in north-central North Carolina and there Gen. Nathanael Greene accepted his challenge to battle.

The battle of Guilford Courthouse was a British victory which left the victor weakened to the extent that he was unable to capitalize on his success. Cornwallis' loss in officers and men was so heavy that his army was "crippled beyond measure." In April, he decided to move to Wilmington, N. C., on the coast, for the avowed purpose of recruiting and refitting his exhausted force. Thus the stage was set for the final campaign of the war.

Cornwallis' next move changed the strategy of the Southern Campaign. He did not believe himself strong enough for field action out of Wilmington and declined to return to Charleston and South Carolina. According to his own statement, "I was most firmly persuaded, that, until Virginia was reduced, we could not hold the more southern provinces, and that after its reduction, they would fall without much difficulty." He made this decision alone, and Commanding General Sir Henry Clinton in New York never approved. On April 25, he marched from Wilmington, reaching Petersburg, Va., on May 20, where he formed a junction with Gen. William Phillips who commanded the British forces already in the State.

By this time there was already a considerable concentration of troops in Virginia. Gen. Alexander Leslie had been sent there with a detachment of troops in October 1780, but he had gone on to join Cornwallis in South Carolina. Shortly thereafter, another British force under Benedict Arnold was sent to operate in the area. To contain Arnold's force, or at least to watch it, Washington had dispatched the Marquis de Lafayette to Virginia to work in conjunction with the Baron von Steuben, and later with Greene. Clinton then countered by sending Phillips with a large detachment to join Arnold. As a result of these and other moves, but by no prearranged plan, the stage was set in May 1781, for Virginia to be the battleground. From the British point of view the subjugation of the province was the tempting prize. For the Americans, the goal was to prevent this, and prevent it they did. The strategy of Yorktown was in the making, but had not yet taken form.

Cornwallis, leading a reasonably well-supplied and able field force of more than 5,300 troops, was opposed by Lafayette, commanding a small force not strong enough to risk battle. Lafayette had been ordered by Greene to remain in Virginia, take command of the troops there, and defend the State. Even though Lafayette expected reinforcements from the Pennsylvania Line under Gen. Anthony Wayne, it would not give him battle strength or even enable him to resist seriously the progress of the enemy. Consequently, the young general's first move was to apply in every direction for more men and supplies.

In the meantime, Cornwallis prepared to force the issue. He selected his field force and dispatched the remaining units to the British base at Portsmouth. After assuring the commander there that he would reinforce him further should a French fleet appear in Chesapeake Bay, he put his army in motion toward that of Lafayette. On May 24, he reached a point on the James River opposite Westover, about 24 miles below Richmond, and began to cross the river. At this point General Leslie arrived with reinforcements, further augmenting British strength. With these men, Cornwallis planned first to dislodge Lafayette from Richmond and then to employ his light troops in the destruction of magazines and stores destined for use by American forces in Virginia and farther south.

The Marquis de Lafayette (Gilbert du Mortier) commanded a division of Continental troops at Yorktown. |

Lafayette, with his small army of about 3,250 men, did not attempt a stand at Richmond, but withdrew northward. The role of this youthful commander was "that of a terrier baiting a bull." He had a heavy responsibility and was faced by an experienced commander in the person of Cornwallis. In the weeks that followed, Lafayette distinguished himself. He continually repeated a series of harassing, threatening, feinting, and retiring tactics. He retreated, usually northward, always maintaining a position higher up the river and nearer the Potomac, thus insuring that Cornwallis would not get between him and Philadelphia.

While encamped in Hanover County, Cornwallis learned that Wayne was only a few days away from a junction with Lafayette. Consequently, he hesitated to move further from his base at Portsmouth, but decided on a quick dash westward before withdrawing. With this in mind he dispatched Banastre Tarleton to Charlottesville to break up the Virginia Legislature then in session—a move that disrupted the assembly and might have led to the capture of Governor Jefferson but for the ride of Capt. "Jack" (John) Jouett to warn him—a ride which is reminiscent of the better-known ride of Paul Revere. At the same time, Cornwallis sent Simcoe to harass Von Steuben who was then at Point-of-Fork on the James River. Von Steuben withdrew, but Simcoe was able to destroy a quantity of arms, powder, and supplies, which had been assembled there, before he rejoined Cornwallis.

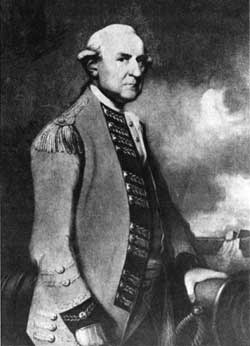

Lieutenant General Earl Cornwallis, Commander of the British forces which surrendered at Yorktown. |

About June 15, with the season hot, his troops tired, and Lafayette still evading him, Cornwallis decided that it was time to return to the coast. He had accomplished as much as possible in the destruction of supplies, he had found no great body of Loyalists to join him, and his opponent was gaining strength daily. He moved east through Richmond and proceeded down the Peninsula toward Williamsburg. Lafayette followed, venturing closer to him all the while.

On June 10, Wayne joined the American force with 1,000 men, and 2 days later Col. William Campbell—one of the famous American leaders at Kings Mountain—provided an additional 600 "mountain men." On the 19th, Von Steuben appeared with his detachment. These reinforcements made Lafayette's corps strong enough for more aggressive action. His strength was now about 4,500, but heavily weighted with untrained militia and short of arms, artillery, and cavalry.

On June 26, there was "a smart action at 'Hot Water Plantation" (Spencer's Ordinary), 7 miles northeast of Williamsburg, where Col. Richard Butler with a detachment of the Pennsylvania Line engaged Simcoe's Queen's Rangers. Following this, the British Army came to a halt at Williamsburg, sending out patrols to various points on the York and James Rivers, including Yorktown.

By this time, the controversy, or misunderstanding, between Corn wallis, in Virginia, and Clinton, his superior, in New York, which involved matters of strategy, the theater of operations, and troop deployment, began to shape the direction of affairs in Virginia. Cornwallis received instructions to take a defensive station at Williamsburg, or Yorktown, reserve the troops needed for his protection, and send the remainder of his army by transport to New York to help Clinton in the siege that he expected there. In the execution of these orders Cornwallis readied his army for a move across the James (a move for which Clinton severely criticized him) and a march towards Portsmouth, where he could direct the dispatch of troops to New York.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |