|

YORKTOWN National Battlefield |

|

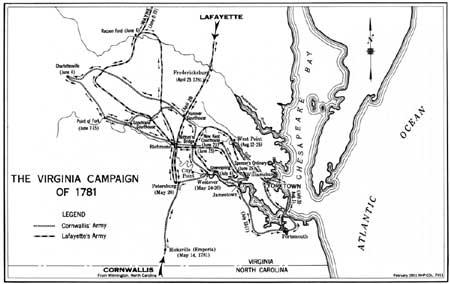

The Virginia Campaign

(continued)

BATTLE OF GREEN SPRING. On July 4, Cornwallis broke camp at Williamsburg and moved toward Jamestown Island, the most convenient point for crossing the James. He sent some troops immediately across the river, but ordered the bulk of the army to encamp on the "Main" a little beyond Glasshouse Point, within sight of Jamestown, as a precaution in the event Lafayette should attempt to hinder the crossing.

Cornwallis was right—Lafayette did intend to strike the British at this unfavorable moment. On July 6, Wayne, commanding the American advance unit, made his way slowly toward the British encampment. Lafayette, cautious and not wanting to be deceived about the enemy strength, went with him to make personal observations. The young general quickly decided that Cornwallis was laying a trap, as indeed he was, but before he could call in his scouts and advance units, action had been joined. Wayne, with only about 800 men and 3 field pieces, came face to face with the major part of the British Army. To halt the advancing enemy, Wayne called for a charge against a seemingly overwhelming force—a brave and daring action by a leader already marked as a man of courage. Both American and British troops fought well, but the charge stopped the British advance momentarily. At this point Wayne called for a retreat, which was effected with reasonable success. Marshy terrain and the approach of darkness prevented effective pursuit by Cornwallis' units. The British losses, killed and wounded, apparently numbered about 70 rank and file and 5 officers. American losses approached 140 killed, wounded, and missing.

The engagement at Green Spring, sometimes called the "Affair Near James Island," was a direct prelude to the struggle at Yorktown. The same forces later faced each other over the parapets on the York. Actual military victory, as at Guilford Courthouse, rested with the British. The most significant result of the encounter, however, may have been the stimulating effect on the Americans of the bravery and courage displayed by soldiers and officers alike. It was another good test of training and discipline—a detachment of American troops had confronted Cornwallis' main force and again they had fought well.

THE BRITISH MOVE TO YORKTOWN. Following the action at Green Spring, Cornwallis continued his move across the James River, and, on July 17, he was able to report by letter to Clinton that the troops which the latter had requested were about ready to sail from Portsmouth. Three days later, Cornwallis learned that all plans had been drastically changed. Clinton now instructed him to hold all of his troops and await further orders. More detailed instructions reached Cornwallis on July 21, including strong words about the necessity for holding a position on the peninsula—the area between the York and James Rivers. Clinton it seems, now thought that Yorktown was a good location for a naval station, offering protection for large and small ships—a vital necessity.

In compliance with his new orders, Cornwallis ordered a careful survey of Old Point Comfort and Hampton Roads to find the best location for such a naval station. This was done by Lt. Alexander Sutherland, of the Royal Engineers, who recommended against Old Point Comfort, which had been mentioned at length in the more recent correspondence between the British commanders in Virginia and New York as a possible location for a base to replace Portsmouth. Cornwallis wrote to Clinton: "This being the case, I shall, in obedience to the spirit of your Excellency's orders, take measures with as much dispatch as possible, to seize and fortify York and Gloucester, being the only harbour in which we can hope to be able to give effectual protection to line of battle ships. I shall, likewise, use all the expedition in my power to evacuate Portsmouth and the posts belonging to it. . . ."

Having stated his intentions, Cornwallis began to take action. On July 30, the British transports, loaded with about 4,500 men, left Portsmouth and set sail for Yorktown, where they arrived on the night of August 1. On August 2, landings were made at both Yorktown and Gloucester. Banastre Tarleton, with his men and horses, crossed Hampton Roads in small boats and proceeded to Yorktown by road, arriving on August 7. By the 22d, the detachment which remained at Portsmouth to level the works completed its assignment and joined the main army. The construction of defenses was begun immediately at Yorktown and Gloucester, a job that Cornwallis estimated would require 6 weeks. On August 31, one of the British soldiers wrote from "Camp Yorktown" that "Nothing but hard labour goes on here at present in constructing & making Batteries towards the River, & Redoubts toward the Land." Actually, the siege of Yorktown began before this task was completed.

Meanwhile, the Americans were still keeping watch on the British. When the British Army moved south toward Portsmouth after the engagement at Green Spring, Lafayette dispatched Wayne to the south side of the James to follow Cornwallis and to attempt to check Tarleton's raiding parties in this area. The Marquis himself took position at Malvern Hill. When Cornwallis left Portsmouth, Lafayette supposed that his destination was Baltimore. Acting quickly, he broke camp at Malvern Hill, and, with his Light Infantry, moved toward Fredericksburg. When he learned that the British were actually "digging in" at Yorktown and Gloucester, he took position on the Pamunkey River near West Point, Va., about 30 miles northwest of Cornwallis' position. Wayne, with the Pennsylvania Line, remained south of the James. From this point Wayne was to have begun his march toward Greene in the Carolinas. On August 25, however, Lafayette learned that the Count de Grasse, with a sizeable fleet, was expected in Virginia, and he immediately cancelled Wayne's orders for leaving the State, requesting instead that he remain where he was pending further instructions.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |