|

SCOTTS BLUFF National Monument |

|

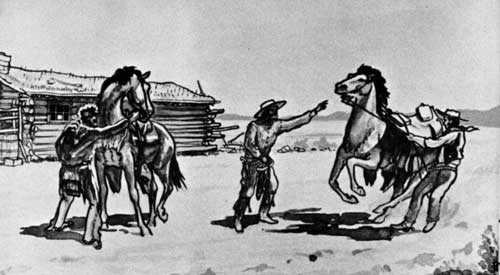

Changing mounts at Pony Express Station.

Original sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

Pony Express to Iron Horse, 1860-69

The California gold rush had not yet abated when strikes of precious metals were made in Nevada and Colorado (1858-59), later in Montana and Idaho (1864). The result was a ramification of the old Oregon-California Trail, with major branches up the South Platte to Denver, and from Fort Laramie northward along the Bighorn Mountains to Virginia City, Mont. (the Bozeman Trail). The new mining communities added their demands to those of Utah and California for improved communication with the States. In the fifties and sixties Scotts Bluff witnessed dramatic changes.

The first mail service up the Platte route was inaugurated by the Mormons; after the army occupied Fort Laramie, military dispatches were carried on regular schedules to Eastern command posts. Public mail service to California began in 1851. By 1860 the Central Overland and Pike's Peak Express Company held a monopoly on mail contracts between the Missouri and the Pacific.

No frontier institution better dramatizes the spirit of American enterprise than the famed Pony Express, fast biweekly mail service. From April 1860 to October 1861 youthful riders on fleet mustangs pounded between St. Joseph, Mo., and Hangrown (Placerville), Calif., braving the elements and Indian dangers. William Russell of the freighting firm was the promoter of the Pony Express. Although financially disastrous, it demonstrated the need for Government mail subsidies.

Pony Express stations were about 15 miles apart and each rider made up to 100 miles at a time, changing to fresh ponies at each station. Stations in the Scotts Bluff vicinity were at Chimney Rock, near present Melbeta (the Scotts Bluff Station at Ficklin Spring, named for a company official), and at Horse Creek. The Scotts Bluff Station, made of massive adobe walls, later became the Mark Coad Ranch. The thrill of watching a Pony Express rider gallop past is vividly described in Roughing It by Mark Twain, who was a statecoach passenger bound for Nevada. The incident took place just east of the pass at Scotts Bluff.

We had had a consuming desire, from the beginning, to see a pony-rider, but somehow or other all that passed us and all that met us managed to streak by in the night, and so we heard only a whiz and a hail, and the swift phantom of the desert was gone before we could get our heads out of the windows. But now we were expecting one along every moment, and would see him in broad daylight. Presently the driver exclaims:

"HERE HE COMES!"

Every neck is stretched further, and every eye strained wider. Away across the endless dead level of the prairie a black speck appears against the sky, and it is plain that it moves. Well, I should think so! In a second or two it becomes a horse and rider, rising and falling, rising and falling—sweeping toward us nearer and nearer—growing more and more distinct, more and more sharply defined—nearer and still nearer, and the flutter of the hoofs comes faintly to the ear—another instant a whoop and a hurrah from our upper deck, a wave of the rider's hand, but no reply, and man and horse burst past our excited faces, and go swinging away like a belated fragment of a storm!

Pony Express rider and the advancing telegraph.

Original sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

The first transcontinental telegraph line, up the Platte route through Mitchell Pass, ended the meteoric Pony Express. In 1860 Edward Creighton of the Pacific Telegraph Company had reconnoitered the Oregon Trail via Mitchell Pass. The active construction of the line took but a few months, in 1861, and in October telegrams were going to California. Service in the early days was hampered by Indians, suspicious of the "singing wires," who frequently burned down the poles. There was an early telegraph station at Fort Mitchell, at the foot of Scotts Bluff.

In 1861, Russell, Majors, and Waddell subcontracted with the Butterfield Overland Mail Company to operate overland stage and mail service over the Central Route (moved up from the Southwest because of the imminent Civil War). There was daily coach service to California via Scotts Bluff until 1862, when Indian troubles required the new operator, Benjamin Holladay, to transfer the route southward, via Lodgepole Creek and Elk Mountain. The days of the famed Concord stage in the Scotts Bluff area were short lived.

As the telegraph made the Pony Express obsolete, so the railroad spelled the doom of the stagecoach and the prairie schooner. The easy gradient over the Continental Divide at South Pass was the geographic reason for the centrally located Oregon Trail. However political rather than geographic reasons dictated the central location of the first transcontinental railroad. During the 1850's there were many "Pacific Railroad Surveys" which did much to fill in the blank pages of Western topography, but none of these touched the North Platte. At the outbreak of the Civil War, President Lincoln decided that a central overland railroad would strengthen the ties of the Union. It was in August 1865, however, before the seasoned engineer and Indian fighter, Gen. Grenville M. Dodge, made his reconnaissance for the future Union Pacific Railroad. Although the route finally selected followed Lodgepole Creek to Cheyenne Pass, the general did examine the North Platte, pausing to sketch Mitchell Pass on August 27. The "iron horse" reached Cheyenne in 1867, and joined the Central Pacific with due ceremony at Promontory Point, Utah, May 10, 1869. This date can be accepted as marking the end of the historic Oregon-California Trail.

"The Gorge, Scott's Bluff" sketched by Dodge in 1865.

From Perkins' Trails, Rails and War.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |