|

SCOTTS BLUFF National Monument |

|

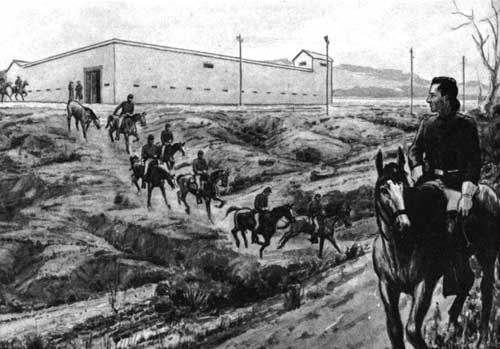

Cavalrymen leaving Fort Mitchell.

Original sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

Warfare on the Plains

In the early 1860's the mounted eagle-plumed warriors of the plains, including the Sioux and Cheyenne, went on the warpath. Scotts Bluff looked down upon many exciting scenes of conflict.

During the days of the trapper and the emigrant, the Indian had been generally peaceful, despite occasional pilferings and "greenhorn" alarms. Indeed, many white traders, such as Robidoux, had freely intermarried with the Indians. The migration of 1849, giving evidence of the white man's strength, coupled with his wanton slaughter of the life-giving buffalo, caused some uneasiness among the tribes. In October 1850, Col. E. V. Sumner with a company of mounted infantry en route to Fort Laramie met and counseled with one band of Sioux at Scotts Bluff. They, like their red brethern throughout the plains, were full of complaints. To quiet them, old mountain man Thomas Fitzpatrick, Indian agent for the Upper Platte, engineered the greatest Indian peace council ever held on the Plains. This was at Horse Creek, a few miles west of Scotts Bluff.

In September 1851 around 10,000 Indians from the tribes of the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Snake, Ree, Gros Ventre, and Assiniboin assembled at Fort Laramie. The U. S. Government was represented by Fitzpatrick; the famed missionary, Father De Smet; Robert Campbell (one of the founders of Fort Laramie); and D. D. Mitchell, superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis. Jim Bridger and other oldtimers showed up to help keep peace among traditional enemies. Because there was not grass enough for the horses of this vast assemblage, the council moved downriver. It was an historic occasion with much colorful pageantry. The negotiations went smoothly, and by "the First Treaty of Fort Laramie" the Indians promised to permit peaceful passage of travelers through their domain in exchange for an annuity of $50,000 in provisions and trade goods.

This peace treaty, like so many others, was soon broken. In August 1854 a misunderstanding between an Oglala Sioux and a Mormon emigrant, compounded by the inexperience of Lt. John L. Grattan from Fort Laramie, led to the massacre of Grattan, 30 soldiers, and his interpreter 8 miles east of Fort Laramie. This was "avenged" in September 1855 by the slaughter of innocent Brule Indians by an expeditionary force under Gen. William S. Harney, near Ash Hollow. En route to Fort Laramie, the cavalrymen trooped through Mitchell Pass with over 200 fresh Indian scalps in their baggage.

In 1862 there was a bloody uprising of the Minnesota Sioux. Hostilities spread to the Plains, with grave danger to lines of communication and army outposts with garrisons depleted by the Civil War. During this period, Fort Laramie was a headquarters post, occupied during the crucial years principally by the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry, under Col. William O. Collins. There was a chain of outposts up and down the North Platte, from Mud Springs near present Bridgeport to South Pass, Wyo. These were frequently harassed by Sioux and Cheyenne warriors. One of these beleaguered outposts was adobe-walled Fort Mitchell, about 2 miles northwest of Mitchell Pass.

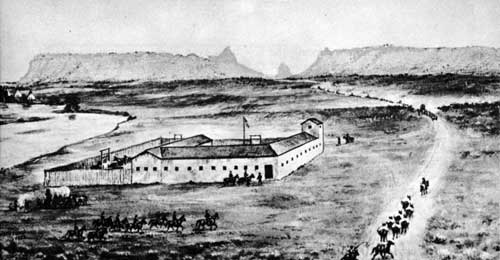

William H. Jackson sketch of Fort Mitchell at Scotts

Bluff.

Initially called "Camp Shuman" for its builder and first commander, Capt. J. S. Shuman, it was constructed in 1864, according to official records, and was last heard of in 1867. The little fort (and later nearby "Scott's Bluffs Pass") was named for Brig. Gen. Robert B. Mitchell (1823-82), commander of the Nebraska Military District, a citizen of Kansas Territory who earlier fought gallantly in the Civil War and later became Governor of New Mexico Territory. Fort Mitchell saw its share of frontier action. Colonel Collins' report of 1865 to the regimental adjutant advises:

Co H has been Stationed at Fort Mitchell 55 Miles East of Laramie on the Platte River. The company participated in the celebrated Indian fights at Mud Springs and Rush Creek where 150 Men under Command of Lt Col Wm O Collins fought from fifteen hundred to two thousand of the dusky warriors, since that time this Company has carried the Mail from Julesberg to Laramie. This has been heavy and laborious duty, yet they have never flinched but have had the Mail through in good time. Besides this company has built one Mail Station, near the noted Land Mark Chimney Rock, besides repairing the one at Mud Springs.

The Battle of Mud Springs in February 1865 was an aftermath of the siege of Julesburg by a horde of Sioux and Cheyenne who were enraged by a massacre of Cheyennes at Sand Creek, Colo. In zero weather the small garrison at Fort Mitchell joined Colonel Collins' forces in an attempt to intercept the north-bound Indians. After skirmishing and light casualties, the Indians withdrew across the North Platte.

A second engagement near Scotts Bluff was known as the Battle of Horse Creek. In June 1865, Capt. William D. Fouts led a company of the 7th Iowa Cavalry who were escorting 185 lodges of supposedly peaceful Brule Sioux from Fort Laramie to Fort Kearny. Between Horse Creek and Fort Mitchell the Indians treacherously attacked, killing Captain Fouts and three soldiers. The Fort Mitchell garrison rode our to aid the Iowans, but again the Sioux retreated across the Platte. Colonel Moonlight at Fort Laramie, advised by telegram from Camp Mitchell, futilely pursued the Indians with a cavalry force.

Other skirmishes, including besieged wagon corrals, ambushes in Mitchell Pass, and troops from Fort Mitchell galloping to the rescue, are reported in the literature, though with scanty evidence.

Fort Mitchell was occupied at various times by units of the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry, the 12th Missouri Volunteers, and the 18th U. S. Infantry. The last identifiable commander was Capt. Robert P. Hughes, of the latter regiment. He was detached there in 1866 by Col. Henry B. Carrington who, with 2,000 troops and 226 mule teams, was en route to construct posts along the Bozeman Trail in the Powder River country. Among the few brief eyewitness descriptions which survive is this impression of Colonel Carrington's wife:

. . . [Scott's Bluffs are] of mixed clay and sand, plentifully supplied with fossils, and throw a spur across the Platte basin so as to compel the traveler to leave the river and make a long detour to the south, or to pass through the bluffs themselves. This passage is by a tortuous gorge where wagons can seldom pass each other; and at times the drifting snows or sands almost obscure the high walls and battlements that rise several hundred feet on either side. . . .

Almost immediately after leaving the Bluffs, and at the foot of the descent, after the gorge is passed, we find Fort Mitchell. This is a sub-post of Laramie of peculiar style and compactness. The walls of the quarters are also the outlines of the fort itself, and the four sides of the rectangle are respectively the quarters of officers, soldiers, and horses, and the warehouse of supplies. Windows open into the little court or parade-ground; and bedrooms as well as all other apartments, are loopholed for defense.

All trace of Fort Mitchell has disappeared but a ground plan of the enclosure is preserved in the Collins Collection of the Colorado Agricultural College. Three authentic contemporary sketches of Fort Mitchell have been discovered; one of 1865 by an unidentified soldier of the 11th Ohio reproduced in The Bozeman Trail; one by an unidentified artist with the Hayden Territorial Survey of 1867, published in U. S. Geological Survey of Wyoming, in 1871; and the one by William H. Jackson, preserved in the Oregon Trail Museum.

Hostilities on the Plains came to a climax when Colonel Carrington built Fort Reno, Fort Phil Kearny, and Fort C. F. Smith on the Bozeman Trail. This trail extended from Fort Laramie northwestward to Virginia City, Mont., scene of a new gold rush. Capt. William J. Fetterman and 80 men were slain in an ambush in December 1866 at Fort Phil Kearny (near present Buffalo, Wyo.). In 1867 Red Cloud's warriors were repulsed at the Wagon Box and Hayfield Fights; but the Government decreed that this trail to the Montana mines must be abandoned, By the second treaty of Fort Laramie, in 1868, the Sioux were granted an extensive hunting domain between the North Platte and Missouri Rivers.

The treaty of 1868 marked the end of major Indian hostilities in the North Platte Valley. In 1870 Red Cloud was induced to visit the Great White Father (President Grant) in Washington; he was also taken to New York City, where he gave an impressive oration in his native tongue to the assembled palefaces. Red Cloud wanted an agency and trading post set up near Fort Laramie, long the traditional camp of the Oglala Sioux. The Government wanted to set up the agency far north of the Platte, on the White River. To humor the Indians, still in a resentful mood, the first Red Cloud Agency was established on the north bank of the Platte, half way between Fort Laramie and Scotts Bluff, at present Henry, Nebr., on the Wyoming boundary. This became the temporary home of more than 6,000 Dakota Sioux (mainly Oglala and Brule), 1,500 Cheyenne, and 1,300 Arapaho.

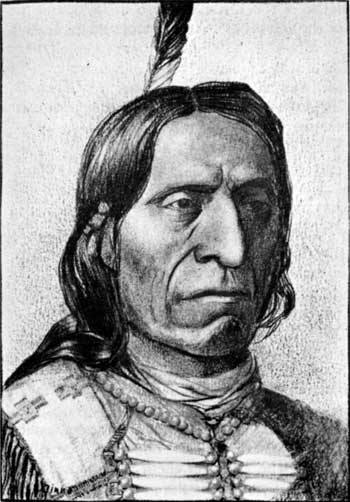

Chief Red Cloud.

Original sketch in

Oregon Trail Museum

Under the prevailing peace policy the Episcopal Church took over the Sioux Agency. Their first agent was J. W. Wham. Unable to control Red Cloud and his excitable warriors, Wham was soon replaced by another churchman, J. W. Daniels. It was not easy for the victors of the Bozeman Trail war to mend their ways. The Sioux ambushed Pawnee buffalo-hunters in 1873 at Massacre Canyon on the Republican River; others joined hostiles on the Powder River in an attack on the Crow Indians and on the Northern Pacific survey parties on the Lower Yellowstone River. In 1873, Daniels finally managed to persuade these "peaceful" Indians to move the agency to White River, where Fort Robinson was established the next year.

The discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, the attempt to reduce further the Sioux reservation, the swift events which culminated in the disastrous Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, and the subsequent rounding up of the scattered Sioux to be placed on Dakota reservations, the killing of Crazy Horse at Fort Robinson—all these events occurred far to the north of Scotts Bluff. The only "wild Indians" to appear again in this area were Dull Knife's Cheyennes, who passed here in 1878 in a spectacular northward flight from their hated reservation in Oklahoma.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |