|

FREDERICKSBURG and SPOTSYLVANIA COUNTY BATTLEFIELDS MEMORIAL National Military Park |

|

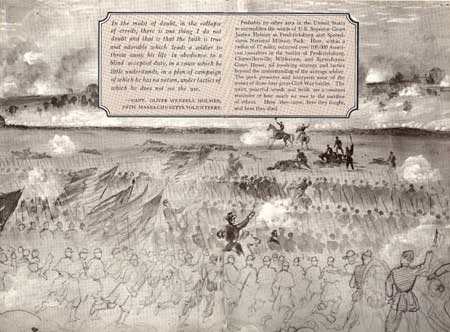

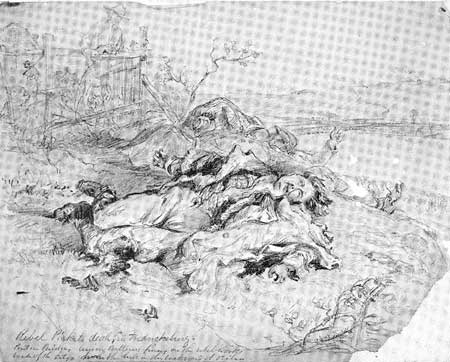

With flashing sword, Gen. Andrew A. Humphrey leas

his Pennsylvania division against the Confederate line on Marye's

Heights, on the afternoon of December 13, 1862.

Courtesy of

Library of Congress.

In the mist of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blind accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has no notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

—CAPT. OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES,

20TH MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEER

Probably no other area in the United States so exemplifies the words of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Holmes as Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. Here, within a radius of 17 miles, occurred over 100,000 American casualties in the battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House, all involving strategy and tactics beyond the understanding of the average soldier. The park preserves and interprets some of the scenes of those four great Civil War battles. The quiet, peaceful woods and fields are a constant reminder of how much we owe to the sacrifice of others. Here they came, here they fought, and here they died.

Part I: A New Thrust into Virginia

FREDERICKSBURG: November—December 1862

"It is well that war is so terrible"

At the head of the navigable waters of the Rappahannock River, Fredericksburg lay midway between the Confederate Capital at Richmond, Va., and the National Capital at Washington, a scant 100 miles apart. Founded in 1727, Fredericksburg by the 1850's was a thriving commercial city of almost 5,000 people, carrying on a direct trade with Europe and the West Indies. Large three masted schooners, moored at the wharves, gave an air of bustling prosperity to the area. In 1861, however, its importance lay in the obstacle it presented, along with the Rappahannock River, to any overland march from Washington on Richmond. As the political, manufacturing, and military center of the South, Richmond became the symbol of secession to the North and the key to military planning on both sides. For 4 years it remained the primary objective of the Union armies in the east. "On to Richmond" was the cry.

There were two main avenues of approach to the Confederate capital: The direct overland route southward through Fredericksburg; and the approach by water down the Potomac, across Chesapeake Bay to the tip of the peninsula between the York and the James Rivers, and then northwestward up the peninsula. In the summer of 1861 the Federal Government, in its first attempt to drive into Virginia and capture Richmond, decided on the over land approach.

Astride this road to Richmond lay Manassas, a small railroad settlement a few miles east of the Bull Run mountains and north of Fredericksburg. Here, Confederate Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard blocked the road with a force of about 22,000 men, while Gen. Joseph E. Johnston commanded a smaller force of some 11,000 troops at Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley. And here, on July 21, Gen. Irvin McDowell brought his 35,000 Union troops on their way to Richmond.

Troops and their transports at the Federal supply

base at Aquia Creek Landing, on the Potomac below

Washington.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

In this first major engagement of the Civil War the Federal army suffered disaster in a nightmare battle of mistakes. Routed from the field, it fled back to Washington in disorder and panic.

President Abraham Lincoln then appointed Gen. George B. McClellan the new commander of the demoralized army. McClellan restored order and discipline and in the spring of 1862 decided to try the water approach to Richmond. This Peninsular Campaign, as it was called, culminated in the famous Seven Days' Battle, when the Army of the Potomac's drive on Richmond was repulsed by Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on the outskirts of the city.

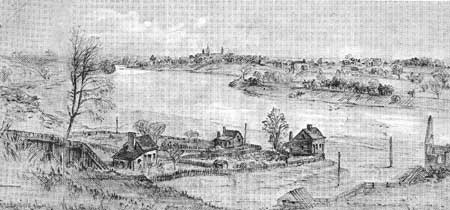

Just before the battle, Civil War artist Alfred R.

Waud sketched this peaceful view of Fredericksburg from across the river

at Falmouth.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Lee now chose to try to stop the next "On-to-Richmond" move before it could penetrate very deeply into Virginia. On August 23 he wrote Confederate President Jefferson Davis: "If we are able to change the theater of the war from the James River to the north of the Rappahannock we shall be able to consume provisions and forage now being used in supporting the enemy."

So Lee moved into northern Virginia to meet Gen. John Pope's threatened overland campaign against Richmond. At Second Manassas (Bull Run) the Union Army was defeated again and withdrew into the fortifications around Washington.

Lee took advantage of this opportunity and made his first invasion north into Maryland, only to be stopped by McClellan at Antietam (Sharpsburg) in September. He then retired into Virginia and prepared to spend the winter recruiting and reprovisioning his army.

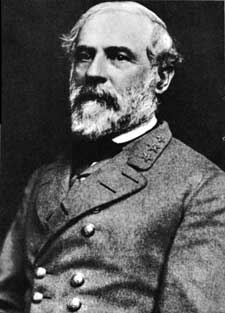

Gen. Robert E. Lee. From photograph by Julian Vannerson. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. From photograph by Matthew B. Brady or assistant. Courtesy, National Archives. |

A FAST MARCH

President Lincoln used the victory at Antietam to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, but both the Government and the Northern people generally were disappointed at McClellan's failure to pursue vigorously the retreating Confederates. When he gave the poor condition of his horses as one excuse for not moving, Lincoln telegraphed: "I have read your dispatch about sore-tongued and fatigued horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigues anything?"

Finally, late in October, the Army of the Potomac advanced cautiously into Virginia, concentrating in the Warrenton-Manassas area. McClellan's immediate objective was Gordonsville, but the movement was so slow, averaging only 5 to 6 miles a day, that Lincoln relieved him of command on November 5 and appointed Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside. General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck telegraphed from Washington: "Immediately on assuming command of the Army of the Potomac, you will report the position of your troops, and what you propose doing with them."

A Federal column moves along the river on the

night of December 11, as flames still rise from the city after the

day-long bombardment.

Courtesy, Library of

Congress.

Burnside, a quiet, unassuming man, had a creditable record as a corps commander and was not generally regarded as being overly ambitious. He did not particularly want the job of army commander. "Had I been asked to take it, I should have declined," he informed Halleck, "but being ordered, I cheerfully obey." From his headquarters at Warrenton he promptly proposed a new plan:

To concentrate all the forces near this place, and impress upon the enemy a belief that we are to attack Culpeper or Gordonsville, and at the same time accumulate a four or five days' supply for the men and animals; then make a rapid move of the whole force to Fredericksburg, with a view to a movement upon Richmond from that point.

There were many advantages to this plan, Burnside was careful to explain. It would enable him to take advantage of Union control of the waterways to establish supply bases at Aquia Creek and Belle Plain on the Potomac; it would allow him to use the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad from Aquia Creek to Richmond; the Army of the Potomac would always be between the enemy and Washington; and it was the shortest overland route to the Confederate capital. At the same time he requested permission to reorganize the Army of the Potomac into three "grand divisions" of about two corps each.

The key to the whole plan, as Lincoln shrewdly realized, was contained in the words "a rapid move of the whole force on Fredericksburg." On November 14 Halleck told Burnside: "The President has just assented to your plan. He thinks it will succeed, if you move rapidly; otherwise not."

Waud's sketch of a captured Confederate. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

Burnside moved rapidly. Early the next morning Gen. E. V. Sumner's Right Grand Division, consisting of Gen. D. N. Couch's II Corps and Gen. O. B. Wilcox's IX Corps, moved out, followed the next day by Gen. W. B. Franklin's Left Grand Division of Gen. J. F. Reynolds' I Corps and Gen. W. F. Smith's VI Corps, and Gen. Joseph Hooker's Center Grand Division of Gen. George Stoneman's III Corps and Gen. Daniel Butterfield's V Corps.

Sumner's advance reached Falmouth, opposite Fredericksburg, on the 17th after a march of about 40 miles, and he immediately requested permission for part of his command to cross the river fords, the bridges having been destroyed. Burnside, however, deemed the plan "impracticable." He did not want "to risk sending a portion of the command on the opposite side of the river until I had the means for crossing the main body." In the event the fords became impassable, he feared the troops would be cut off. Consequently, he decided to await the arrival of the pontoon boats, expected momentarily, to enable him to bridge the river. By November 19 Burnside and the rest of the Army of the Potomac were encamped on Stafford Heights opposite Fredericksburg.

The suddenness of the move surprised Lee. He had recently reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia into two corps under Gens. James Longstreet and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, and his plan of defense against McClellan's slow advance had been "to attempt to baffle his designs by maneuvering, rather than to resist his advance by main force." As a result, Jackson's corps was now in the vicinity of Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley, while Longstreet's was encamped at Culpeper, about 35 miles northwest of Fredericksburg. Only a token force held the city itself.

These Confederate pickets, sketched by Arthur

Lumley fell while opposing the Federal crossing of the

Rappahannock.

Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Despite the sudden Federal move, Lee showed no inclination to unite the separated wings of his army. He was not yet convinced that Fredericksburg was Burnside's only immediate objective. On November 18 he wrote Davis: "It is possible that he may attempt to seize Winchester, Culpeper, and Fredericksburg . . ." But even if Fredericksburg was the only objective, Lee at this time did not desire to make a stand there, as he saw no particular military advantage in the position. He told Jackson November 19: "I do not now anticipate making a determined stand north of the North Anna River," which was approximately midway between Fredericksburg and Richmond. As a precautionary measure, he ordered Longstreet's corps to Fredericksburg, although admitting as late as November 23 that he was "as yet unable to discover what may be the plan of the enemy."

Finally, on November 26 he ordered Jackson to join him. Lee had now decided to resist the Federal advance along the Rappahannock. "My purpose was changed," he stated, "not from any advantage in this position, but from an unwillingness to open more of our country to depredation than possible, and also with a view of collecting such forage and provisions as could be obtained in the Rappahannock Valley."

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |