|

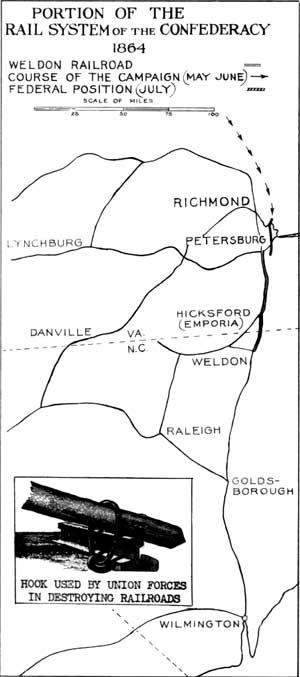

TWELVE THOUSAND IN FOR A SIXTY-MILE RAILROAD

The Capture of the Petersburg and Weldon Line in 1864

By Raleigh C. Taylor,

Junior Research Technician,

Petersburg National Military Park

Little boys are told, doubtless with good reason,

that they should not put pennies on the tracks since possibly the

locomotive would be derailed. One way and another, however, it always

costs more than a penny to stop a train, just as it costs a great many

pennies and sometimes a few lives to start one, if we count the

construction of the road.

The Petersburg and Weldon Railroad, one of the

earlier Virginia lines, was relatively inexpensive in construction.

Certainly its 60 miles of right-of-way crossed neither mountain nor

desert, and it appears that the story of its building has left no deep

impress on American history. Not so for its destruction, for the

stoppage of that one line had significant military consequences during a

period which equals the time in which Napoleon moved from exile to

empire and back -- a hundred days.

It was in the summer of 1864, when the nation still

awaited the outcome of Grant's struggle with Lee, begun in May on the

Rapidan River but now shifted, after many battles and unprecedented

losses, 70 miles southward to Petersburg. The Confederates, holding

Petersburg and Richmond, had to draw supplies from farther south. If

Grant could cut the railroads in that direction, Lee would be compelled

to leave his entrenched line around the two cities.

The Petersburg and Weldon thus had become

increasingly important in the campaign. As early as May 7, while Grant

was still in the Wilderness, Federal cavalry from Butler's army had

interrupted traffic. Again in late June raiders crossed it once more,

and this time the infantry reached the rails. The effort cost them 2,000

prisoners and gave to General William Mahone his first victory in the

defense of Petersburg. Nevertheless, the blue-coats remained on the road

or in easy reach of it for some days. With Early rapping at the gates of

Washington, however, there was urgent call for troops and the road was

abandoned once more to the Confederates.

In July and August the wheezy locomotives still were

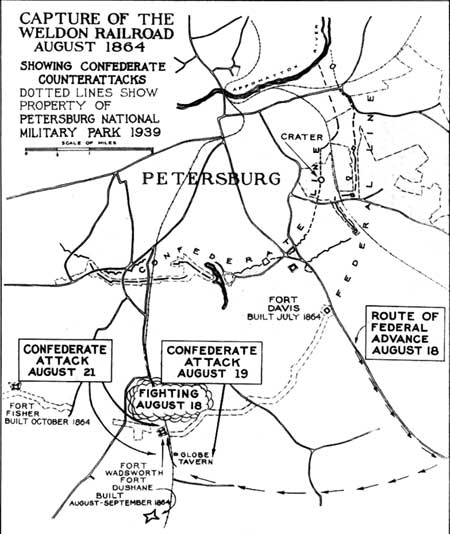

rolling between Weldon and Petersburg. In mid-August, General Gouverneur

K. Warren, a small man in a large black hat, with a heavy sword and a

long bird nose, the engineer officer who had seen and defended the key

position at Gettysburg, was given his greatest assignment. With a

semi-detached left wing finally consisting of 20,000 infantry, he moved

out to take possession of the railroad. His column advanced swiftly,

bothered more by dust and sunstroke than by the shots from Confederate

pickets. A storm came in early afternoon and with it one of the

divisions moving northward was attacked by the Confederates in the thick

woods. The battle had no particular result except to show that the road

was not to be taken without trouble.

Next day, in continued rains that made the wagon

roads impassable, the Confederates, having realized the seriousness of

Warren's expedition, gathered all available strength to thrust it back.

The red-bearded A. P. Hill, who was to die when Petersburg fell, did his

best to postpone the day. His wiry, high-voiced "toy soldier" General

Mahone pushed his division down through the woods to the west of Warren

and, although the artillery pounded them back from the open ground

beyond, they brought in a heavy "bag" of prisoners, just as they had

done two months before near the same spot.

Two days later the Confederates with a still stronger

force tried once more, this time from the west, but the chief result was

the 350 dead and wounded left in Federal hands. With that failure Lee

decided that the game no longer was worth it, or at least that there was

no use pushing his thinning regiments against well established

lines.

The Federals began a thorough destruction of the rail

line, extending the work southward as more troops arrived, this time

under Hancock, the corps commander of whom Grant said that he never

committed in battle a blunder for which he was responsible. Yet

Hancock's troops, two miles south of Warren's line, were struck and

surrounded by A. P. Hill and Hampton's cavalry. Hill, sick, directed the

attack from a blanket on the field. The Federals were broken and lost

nine cannon. August 25 was a black day for Hancock who expressed the

hope that he might never leave that field. He and Miles (later to

command the army) and Gregg of the cavalry saved what they could from

the wreckage.

The tale of the Weldon was not over quite yet. In

December General Warren was sent out again, on a miserable march through

rain and sleet, to complete the destruction southward. He reached

Emporia, burning the ties and heating and bending the rails from the

Nottoway to the Meherrin. The main event, besides the weather, was the

finding of considerable quantities of applejack in almost every house, a

circumstance which caused delay and straggling and the rise of a rumor

that the country people had killed some of the soldiers. The

consequences was the unauthorized burning of many houses on the return

march.

Thus, before the end of 1864, the Petersburg and

Weldon Railroad was disposed of entirely as a military factor. Forty

miles of it was a complete wreck. Leaving out labor and property loss,

the work had cost the Federal army 9,500 men in killed, wounded and

missing --- more than 200 for every mile of wrecked track. Confederate

losses are estimated at 2,339. It is doubtful whether any other railroad

in the world has been more thoroughly baptized in blood.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|