|

COLD CHISELERS AT FORT PULASKI

A Footnote to Two Wars

BY FREDERICK L. RATH, JR.,

ASSISTANT HISTORICAL TECHNICIAN

Historians like to draw analogies between the past

and the present, and to say, with a kind of triumphant sneer, "There is

nothing new under the sun." The habit is a bad one; perhaps there should

be a law against such self-conscious effort, particularly since the

historian offers his contribution only after the event.

Nonetheless, an opportunity too good to be passed has

been offered by the recent military operations in Europe. The American

public has watched with great interest the successful German offensive

against the reputedly impregnable Maginot Line and its prototypes. One

phase of these operations, that against the advance pill boxes covering

the greater fortifications, is not dissimilar to a plan evolved by

Federal forces on the Savannah River in 1862. The tactics of the

Germans, so far as has been gleaned from present accounts, involved a

use of flame throwers, hand grenades, and other special implements of

war. Exactly how the operations were made effective is not yet known.

The Germans were successful, at any rate, either in forcing their way

into the small forts or in having the defenders open the forts to

them.

In October 1861, General T. W. Sherman and more than

12,000 Federal soldiers embarked from Norfolk, Virginia, for an

undisclosed destination. The sealed orders under which the huge flotilla

sailed were opened at sea, after a violent hurricane wrecked several

ships. The expedition, it was then learned, was to rendezvous at Port

Royal Sound, South Carolina. Early in November, Forts Walker and

Beauregard, guarding the entrance to the Sound, were taken, and the

Union forces set up their headquarters on Hilton Head Island, about 15

miles north of the mouth of the Savannah River where stood Fort Pulaski,

garrisoned by some 400 Confederates. A natural objective was the seizure

of this fort, which controlled ingress to and egress from the important

cotton port of Savannah.

In order to invest the fort, it was necessary to cut

it off from its source of supply, the city itself, so expeditions were

sent out early in 1862 to occupy the islands surrounding Cockspur

Island, the site of Fort Pulaski. North and west of this island, along

the Savannah River, lay a series of marsh islands on which batteries of

guns were to be erected. This task was entrusted to the Forty-Eighth

Regiment, New York State Volunteers, and the Seventh Connecticut

Volunteers.

Accordingly, in February 1862, batteries were set up

on Jones and Bird Islands, which were separated by the North Channel, or

shipping channel, of the Savannah River. The story of the placing of the

guns, a laborious task involving the building of cause ways across the

marshes, can be told at another time. By February 20, Battery Vulcan and

Battery Hamilton were in position to stop all traffic between Savannah

and Fort Pulaski.

The story that follows comes from the pen of the Rev.

D. C. Knowles, Captain, Company D, Forty-Eighth New York, who describes

graphically the plans of the "Cold-Chisel Brigade."1

And now I come to an episode that is a type of many a

curious plan that our civil war brought forth. Probably no contest ever

produced so many novel expedients to circumvent an enemy as were born in

the fertile brains of our inventive Yankee soldiers. Powder gun-boats,

monitors, and mines hurling forts into the air are samples of these

extra-military expedients for defeating a watchful foe. The event I am

now about to relate is not a whit behind the chiefest of them in hazard

and reckless audacity.

About the middle of March two deserters from the

rebel lines came into our brigade and reported the existence of a

steamer at Savannah clad with railroad iron, after the order of the

celebrated Merrimac. They said a movement was on foot to run the vessel

down with a body of troops, capture our forts on the banks of the

Savannah, and thus open the way to the relief of Pulaski.

Certain reports of officers making reconnaissances of

the river seemed to corroborate the existence of such a vessel, and the

fears of our officers were aroused for our safety and the success of our

enterprises. Schemes for defence were at once devised, and the plan I

now give in detail was adopted.

It was supposed that the vessel lying low in the

water, with sloping sides of iron like the roof of a house, would steam

down the river and anchor directly between our batteries, of which we

had two, one on either bank, and proceed boldly to shell us at close

range, while all our shot in reply would fly harmlessly from her

invulnerable covering. In the mean time the infantry would attack us in

the rear, cut off retreat, and take us all prisoners at their

convenience. The line of defence, therefore, must include the capture of

the vessel by some expedient. The plan devised in the fertile brain of

somebody was to take six common row-boats, three on either side of the

river, man each of them with six oars-men, six soldiers, and an officer.

The soldiers were to be armed with revolvers, hand-grenades,

cold-chisels, and sledge-hammers. The boats were to be well supplied

with grappling-irons and ropes. Thus equipped, when the vessel came, the

whole expedition was to row out from either shore, board the vessel by

means of ropes and grappling-irons, keep the gunners from the guns by

the free use of hand-grenades thrown in the port-holes, and cutting

through the iron roof by means of the cold-chisels and sledge-hammers,

get inside the vessel and capture her, crew and all. Such, in brief, was

the line of defence. Suffice it to say, the boats were selected, the

material all sent down to the batteries, and the officer in command of

the forts directed to select some one to lead the forlorn hope. I was

called to the command. Selecting two lieutenants as assistants, we

picked our crews, drilled our men, and awaited the final hour.

While making preparations, Captain Hamilton, a

prominent officer in the Third Artillery of the regular army, came down

to inspect our progress, and report our condition. He sent for me to

visit him in the Lieutenant-Colonel's tent. I explained our

preparations, and asked advice. One point seemed to me not to have been

well considered. I said to him, "Captain, that vessel has steam and an

engine, and it seems to me if we should succeed in getting a force on

her sloping sides, and threatening to take her, they would slip their

cables, steam up the Savannah, and carry us off to jail with all

dispatch." "But you must stop her," said he. "Well, how?" was my reply.

He sat a moment in silent meditation, when he broke out: "I do not know

any better way than to take strong ropes, fasten them to her anchor or

some part of the vessel, and then attach the other end to the screw, so

that when the wheel starts the rope will wind up and stop its

revolutions." "Not a very easy thing to do it strikes me," said I, "in

such a rapid current as this river, and that too while cannon are

thundering in our very faces." "Well," said he, "it is a desperate case,

and we must hold these batteries at any cost. You must do the best you

can, at any rate."

Just at that moment a thought struck me, suggested by

my knowledge of the construction of a steam-boiler and the presence of

the cold-chisels. I ventured to suggest it as a new plan of offence.

"Captain," said I, "why could we not board the vessel, strike at once

for the smoke-stack, and cutting a hole in it, throw down a bomb-shell,

blow up these tubes that run through the boiler, and thus let out the

steam and scald the crew, and take the whole institution at a blow."

The Captain sprang to his feet, with a face all

radiant with joy, and with many big words which I do not desire to

repeat, declared that the thing should be done, and consequently a huge

bomb-shell, with fuse all ready, was placed in each boat as a part of

our armament. And while we waited the coming of our foe we wrote to our

friends the possibility of our fate, and talked together of a grave in

the muddy flood of the Savannah. For we all felt assured that nothing

less than an interposition of Providence could save us from certain

destruction. To row half a mile in the face of such a foe, in such a

rapid current, in crowded boats, and board a vessel under such

conditions, was an enterprise that had in it few chances of success.

Disaster in all probability would have been the end of such an

expedition. And yet in the face of these convictions we entered on the

project with all the ardor of assured victory. The devoted band was

denominated "The Cold-Chisel Brigade," and when the enterprise was

finally abandoned the cold-chisels were seized as souvenirs of a project

that gained at the time quite a local notoriety.

Suffice it to say the report was false. No such

vessel then existed; and when General Hunter took command of the

Department he made an early visit to the batteries to see what the

"Cold-Chisel Brigade" was proposing to do, and with the curt remark,

"What fool got up that plan?" he ordered it disbanded.

A variation of this story offers a humorous

sidelight. Major General Quincy A. Gillmore, in charge of the operations

against Fort Pulaski, gave this version:

The 48th New York, which furnished the guard for the

battery, had not a reputation for conspicuous sanctity, but it is

doubtful whether one story told of then would not suffer in point by

contact with hard facts.

There was an iron-clad in Savannah named the Atlanta,

but commonly known as the "Ladies" gun-boat, from the fact that means

for building it had been largely supplied by contributions of jewelry

from the ladies of the city. Some time after our occupation of Jones

Island, it was reported that the Atlanta was coming down to shell us

out. The thoughts of the battery-guard naturally turned toward measures

for meeting such an attack, and it was resolved to fire shot connected

by chains and so tangle her up and haul her ashore. When the question

arose how they would get into their iron-bound prize, the officer in

command of the detachment was ready with his solution: "I've got the men

to do it." Then he paraded his men, and informed them of the facts.

"Now, said he, "you've been in this cursed swamp for two weeks, up to

your ears in mud, - no fun, no glory, and blessed poor pay. Here's a

chancd. Let every one of you who has had any experience as a cracksman

or a safe-blower step to the front." It is said that the whole

detachment stepped off its two paces with perfect unanimity.

1Abraham J. Palmer, The History of the

Forty-Eighth Regiment New York State Volunteers, In The War for the

Union. 1861-1865. (Brooklyn, New York, Veteran Association of the

Regiment, 1855) pp. 33-35.

2"Siege and Capture of Fort Pulaski,"

Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (New York, The Century Co. 1887),

Vol. II, p. 8, note.

|

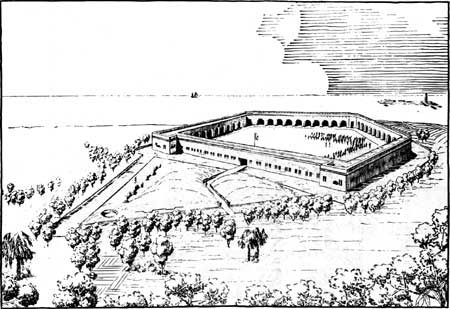

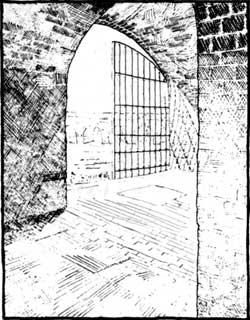

25,000,000 BRICKS

Fort Pulaski is a physical monument which

commemorates the end of a distinct chapter in the ever-changing

development of military science. Its massive walls, in which

approximately 25,000,000 bricks were placed by patient masons over a

period of nearly 20 years, still bear today the historic scars of a

30-hour bombardment by federal artillerymen on April 10-11, 1862, a

bombardment which demonstrated to the world for the first time the

tremendous battering power of the new rifled cannon. Those walls, from 7

to 11 feet thick, crumbled away before the savage blows delivered by

cone-nosed projectiles which spun and whirled through the air over a

low, mile-long, arc. Surrender of the "impregnable" fortress by the

Confederates who had seized it at the outbreak of the War Between the

States gave notice to military engineers that the day of brick citadels

had passed forever.

Cockspur Island, called "the key to our province" by

colonial writers of Georgia because of the strategic location at the

mouth of the Savannah River, was selected in the early 1820's as the

site of the present fort. Construction began in 1829 and went on fairly

continuously until 1847, but the fortress was never completed with

respect to its armament, only 20 of 146 contemplated guns having been

mounted. It became a military prison in 1865 and three Confederate

cabinet members were confined there. Abandoned as an active post in

1885, it fell into oblivion except for a short period during the

Spanish-American War. Finally, the site was proclaimed a national

monument in 1924, and since 1933 a program of renovation and

preservation has made the historic structure accessible to visitors.

|

|