|

DIGGING UP PREHISTORY

An Archeological Survey of the Natchez Trace

BY J. D. JENNINGS,

ASSOCIATE ARCHEOLOGIST

Archeology as a word, and as an activity, has

a definite meaning to every one. It calls up a vision of exciting

adventures in desert wastes, or tangled jungle growths, adventures which

but only prelude the triumphal, thrill of discovering a huge ruined

city, littered with golden debris and dotted with tombs containing

fantastic baubles. Many people have also become aware of the equally

informative, if less glittering, "dirt" archeology now going on in

eastern North America, Possibly because romance usually lies across

international boundaries, the sweaty diggers in the United States are

rarely glamorous figures, nor do their mild adventures rate Sunday

supplement space. Plodding along without benefit of such stimulus, the

archeologists of the South are steadily building up a composite picture

of the pre-European Indian populations of America.

As is true in all scientific endeavor, many men labor

here toward a common aim. The ultimate story is the sum of their

contributions. In the past decade governmental agencies, cooperating

with other public institutions, have conducted in the South some of the

world's most extensive excavations. Major W. S. Webb's TVA-PWA

explorations in the valley of the Tennessee; J. A. Ford's Louisiana

State University-WPA work in Louisiana; A. R. Kelly's Smithsonian-WPA

activities in Macon, Georgia; D. L. DeJarnette's Geological Survey in

Alabama in cooperation with Major Webb; Robert Wauchope's University of

Georgia-WPA reconnaissance in North Georgia; Major Webb's University of

Kentucky-WPA work in Kentucky; T. M. N. Lewis' University of

Tennessee-TVA-WPA work, first in association with Major Webb, and later

alone, in East and West Tennessee --- these comprise a list of the major

continuing archeological undertakings financed largely by the relief

organizations. Besides these, many other valuable projects, albeit of

shorter duration, were financed in North Carolina, Tennessee, Florida,

Georgia, and other states. There is little wonder, therefore, that much

information is now available, although even yet so little is the

Southeast known that after nearly every excavation small segments of the

entire prehistoric mosaic shift and rearrange their relation to the

whole pattern.

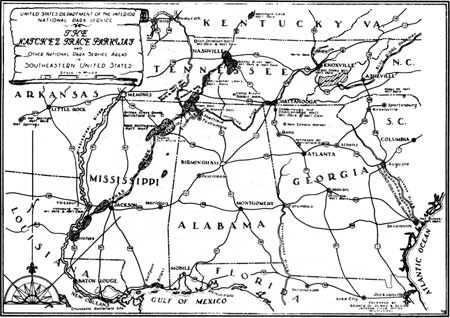

Stippled portions show roughly the areas which have been explored

archeologically

(click image for an enlargement in a new window)

Interestingly enough, little of the interest shown by

students is localized in the State of Mississippi. More than 300 miles

of the Natchez Trace lie in Mississippi in the northeast-southwest

line1 shown on the accompanying map. Almost unknown

archeologically is the area it cuts across. At its southern terminus, J.

A. Ford2 and Moreau B. Chambers3 have done good

work, but for the major length almost nothing is published. Realization

of the near lack of information, although rich unstudied remains were

known to exist, prompted the initiation in 1939 of a Natchez Trace

National Parkway archeological survey which would be concerned not only

with Mississippi but also with the entire length of the Trace.

While the purposes and needs guiding the operation of

the Trace survey are implicit in the foregoing paragraphs, and there is

the ultimate aim of contributing a few paragraphs to the final outline

of pre-European Indian history, the immediate aims are definite and

urgent. Five major objectives have been outlined, although the first

three listed are of the more urgent nature,

First, comes the search for sites for purposes of

parkway location and for compilation of the base historic sheet. This

first activity is, in addition, an important archeological technique,

inasmuch as a rapid surface reconnaissance permits the collection of

surface material, where this exists, and gives a partial preview of the

cultural horizons represented by the content of the sites visited.

Second, upon the completion of the preliminary

analysis of survey collections and other data, sites of potential

scientific value or of outstanding intrinsic display appeal, are

recommended for preservation either through acquisition as parkway

right-of-way or by other public agencies. Action has not yet been taken

on the recommendations submitted.

Third, aside from the sites eventually acquired, many

other sites discovered by the survey will lie too far from the motor

road for acquisition, or may not be spectacular, even though there is

evidence from surface material that several cultures, or a new variant

of one already recognized, once existed on the site. In order to verify

the suggestions derived from surface material or to check on the

scientific value implied, it is necessary to conduct digging operations

in varying degrees of intensity. The excavation program is primarily for

the purpose of filling out the blanks in the archeological framework

through the addition of new scientific data.

Fourth, if excavations are conducted on

federally-owned Natchez Trace Parkway lands, any features of interest,

such as a well-preserved burial, a firepit, a house-pattern, or other

object which can be preserved or restored, should be dug carefully so as

to preserve it entirely and protect it until a field display can be made

available to users of the Trace.

Fifth, the last point is allied closely to the

preceding in that the survey is in the larger view collecting data for

use in the informational program of the parkway. It is further hoped

that contributions to the general knowledge can thus be made.

Already referred to is Mr. Gardner's lucid account of

the Natchez Trace and its early history. The account tells how the Trace

came into being: as a prehistoric highway, no less. Its purpose was to

link tribal centers for commercial and social reasons. In Mississippi

alone three such tribes, similar in language, but with differing habits

of living, were connected by the trail.

In the South, the autocratic Natchez, famous for

their bloody funeral sacrifices, their rigid caste system, their austere

sun-worshipping religion, and their stubborn resistance to French

insolence, enjoyed the respect and fear of their red neighbors. East and

north of the Natchez tribe lived the Choctaw, related in language but

with a less noteworthy set of religious and ceremonial practices. Burial

rites, though involving less bloodshed, were still not calculated to

soothe a queasy stomach. The corpse was stored upon a rack or scaffold

until the passage of time had removed most of the flesh from the bones.

Next a pair of specially designated operatives, with long fingernails

for the purpose, cleaned the vestiges of flesh from the bones, and

placed then, with appropriate ceremony, in a charnel house where other

baskets of bones lay. When an adequate number had accumulated, all were

stacked in a selected spot, and were covered with a low mound of

earth.

In other respects we are told that the Choctaw were

not much given to ceremony. Very industrious, these Indians were the

best farmers of the Southeast, growing corn and other products in excess

of their needs, and diverting their surplus into trade. The Choctaw were

good warriors although not given to aggression; they defended their

homeland but did not seek to expand their territory by conquest. But in

northwest Mississippi the gallant Chickasaw, a small hardy tribe of

excellent warriors, were respected as fighters by red and white alike.

Although farmers, they also ranged as far north as the Duck River in

Tennessee on hunting and war expeditions. They also kept up an

intermittent feud with the French and Choctaw to the south; the tribe

was always friendly to both British and American overtures. Several

interesting ceremonies were practiced but burial was accomplished

quietly by placing the deceased with fitting solemnities, in a shallow

pit beneath his bed.

From the Chickasaw country the Trace led over the

Tennessee River (in what is now Alabama) and on along the ridges of

central Tennessee to and beyond what is now Nashville. Part of this

territory was claimed as a hunting preserve by the far-ranging Chickasaw

and part by the Cherokee of North Carolina and East Tennessee, but no

extensive long-lived settlements are reported.

So much for the recent Indian occupation, recorded by

early explorers, missionaries, traders, and government officials. Before

the Europeans saw the country, however, a long series of Indian

civilizations had appeared, flowered and been displaced by more vigorous

newcomers. What many of these early cultures were like is already partly

known. The Natchez, for example, were preceded by four well-defined

cultures which have been discovered and described by Ford and his

associates. A related series, but by no means identical, has been less

completely observed beneath the Choctaw remains. Before the Chickasaw

came to the place where they were discovered by the whites, one or more

vaguely outlined periods had already run their course, while in the

Tennessee Valley a long series of occupations go back 1,000 or more

years to a time when the red men did not even possess knowledge of

pottery making or agriculture, but lived on such animals, shell fish,

and wild vegetable foods as they could collect. No evidence as to their

language or many of their customs has come down to the present day. Nor

is it certain just what relation these earlier tribes were to the last

ones in the region. In some cases the ages of the various periods and

the interrelation of the tribes (those on the Tennessee River to those

on the Mississippi River in Louisiana, for example) are not yet

known.

The scientific problems therefore, are to gather data

along portions of the Trace where least exploration has been done, to

search for relationships between the archeologically discovered old

cultures and the historically described recent tribes, and to continue

to search for light on the relationship to each other of the old,

incompletely known civilizations and for data about their actual

ages.

Because the Natchez Trace cuts across tribal boundary

lines, the range of archeological interest is necessarily greatly

widened. In order to tell the complete story, it will be obligatory to

borrow data from many sources and attempt to synthesize it with any

original findings reported by the survey.

Since the scope of the effort is so ramified, a

random controlled sampling of the sites along the roadway is being

practiced rather than an immediate attempt to locate each site in the

vicinity of 450 miles of parkway. This is done so that an early

delineation of scientific problems may be made, and the direction where

answers might be expected can be indicated. The map shows the path of

the Trace and the areas sampled by the survey thus far. A report of the

survey activities has been prepared and is now ready for a limited

National Park Service distribution.4 This report shows that

additional research on the problems mentioned two paragraphs above will

take certain directions. It also demonstrates that a beginning was made

toward determining the predecessors of the Chickasaw.

Enough data have been recovered to warrant initiation

of an excavation program. This began only recently on a Chickasaw site

just south of Tupelo, Mississippi. Already the finds are expanding our

knowledge of this enigmatic tribe. While the party is operating in this

region, some of the very old sites will be sampled also. With the birds,

the excavation party will go south, and after January 1, 1941,

operations will be in the vicinity of Natchez, Mississippi, where the

Natchez Indian villages and older sites will be examined. Periodic notes

on progress of the excavation will be forwarded to The Regional Review

during the coming months.

1Malcolm Gardner, "The Natchez Trace - An

Historical Parkway." The Regional Review, Vol. II. No. 4, April 1939,

pp. 13-18.

2Analysis of Indian Village Site

Collections from Louisiana and Mississippi, Anthropological Study

No. 2, Department of Conservation, Louisiana Geological Survey.

3Associated with Mississippi State

Department of Archives and History.

4Archeological Survey Natchez Trace,

September 3, 1940.

|