|

ACADIA

The Sieur de Monts National Monument and its Historical Associations Sieur de Monts Publications XVII |

|

SIEUR DE MONTS NATIONAL MONUMENT

GEORGE BUCKNAM DORR.

CUSTODIAN.

The time is fast coming when National Parks and Forest Reservations, places of beauty and refreshment within occasional reach by all, will be recognized as fundamental needs, needs of the people, in our national life. The West, aided by the Government's great ownership of lands, has led the way in this and shown its foresight. In the East, where gifts of land or purchases by the Government were necessary, the need has been longer in obtaining recognition, the first step toward meeting it by the establishment of a purely recreative area under the National Park Service being taken by the Secretary of the Interior last July, in recommending to the President the acceptance of the Sieur de Monts National Monument.

|

This area, not a purchase by the Government but a gift from citizens, includes the mountainous and finest landscape portion of Mount Desert Island on the coast of Maine, whose crowning glory in a resort and scenic sense that island is and has been for the last half century.

Technically termed a Monument because created by the President and Secretary of the Interior under the authority given them by the so-called Monuments Act of 1906 and because of its historic interest, it is by nature, beauty, and resort importance a true National Park in every popular sense and destined when developed to become one of the most widely visited and recreationally useful park areas on the continent.

It cannot long stand alone in the East; the human need for such areas of refreshment within reach of our great eastern cities and those of the fast-crowding lake and Mississippi regions is too serious for that. But it will in all likelihood remain unique forever as the one national park — using the word in its true, popular sense — bordering on the sea; and it must remain always supreme in landscape interest and refreshing quality upon our eastern coast. Beautiful as it is in other ways, this is its unique possession, that it is the only tract of national park land in the country offering to its visitors the refreshment, the ever-varying interest and beauty and the limitless expanses of the ocean — in contrast to the magnificent domains of mountain lands, western or eastern, that its companion parks may offer.

|

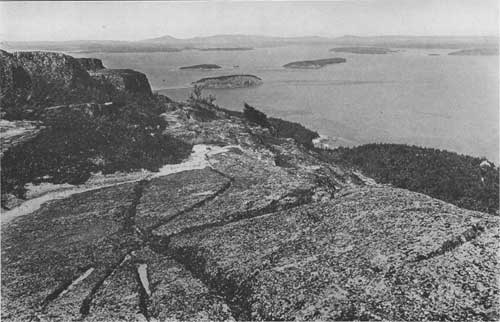

| FRENCHMANS BAY AND THE GOULDSBOROUGH HILLS — FROM THE SUMMIT OF NEWPORT MOUNTAIN |

Because of this and the great human value of the tract as a recreational area, guarded in beauty and made free to all, it is felt that its name should be made indicative of its character and tell more plainly what it offers. To this end a bill, approved by the National Park Service, is being introduced in Congress by Senator Hale of Portland, Maine, familiar from boyhood with the beauty and resort importance of the region, asking that the name be changed from the Sieur de Monts National Monument to the Sieur de Monts National Park. A similar change is already planned in a conspicuous instance in the West, that of the Grand Canyon, a true park area in every popular sense, but technically termed till now a National Monument since created, like the Sieur de Monts, by act of the Administration.

Physically, the Sieur de Monts National Monument is a bold range of seaward-facing granite hills, extraordinarily mountainous in character and wonderful in the variety, the interest and beauty of the climbs they offer. One only, but the highest, rising from the border of the ocean over fifteen hundred feet, offers opportunity for road construction. When, sooner or later, such a road — one by no means difficult to build — shall be constructed, restoring along a better route the old buckboard road which formerly led up to a hotel upon the summit, it will become at once, with modern motor travel, one of the great scenic features of the continent. As one ascends, superb views of land diversified by lakes and bays and stretching far away to distant hills, disclose themselves successively, and when one reaches the summit, the magnificent ocean view that opens suddenly before one is a sight few places in the world can parallel. The vastness of the ocean seen from such a height, its beauty both in calm and storm, and its appeal to the imagination yield nothing even to the boldest mountain landscape, while the presence of that cool northern sea, surging back and forth and deeply penetrating the land with its great tidal flood, gives the air a stimulating and refreshing quality comparable only to that found elsewhere upon alpine heights. And as on alpine heights the herbaceous plants that shelter their life beneath the ground in winter bloom with a brilliancy and flourish with a vigor rarely found elsewhere, so here the ocean presence and long northern days of summer sun combine with the keen air to make the gardens of the Island famous and the national park-lands singularly fitted to serve as a magnificent wild garden and plant sanctuary, at once preserving and exhibiting the native plants and wild flowers of the Acadian region which the Monument so strikingly represents.

|

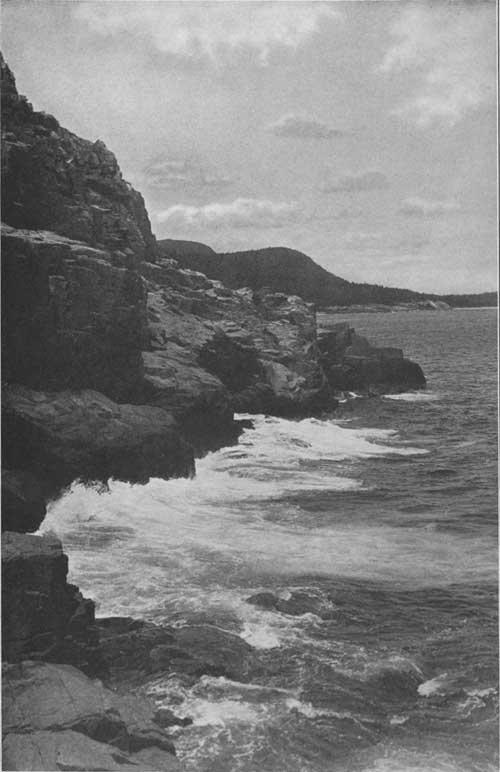

| SURF AT OTTER CLIFFS |

This native quality of the place is noted, curiously, in Governor Winthrop's Journal, when he came sailing by one early summer day in 1630 on his way to Salem, bringing its Charter to the Massachusetts Colony whose Governor he was to be, and found "fair sunshine weather and so pleasant a sweet air as did much refresh us; and there came a smell from off the shore like the smell of a garden."

As a bird sanctuary, too, these parklands, placed as they are directly on the great natural migration route of the Atlantic shore and widely various in favorable character, need proper guardianship only to become a singularly useful instrument in bird life conservation, while adding not a little through the presence of the birds to their own interest and charm.

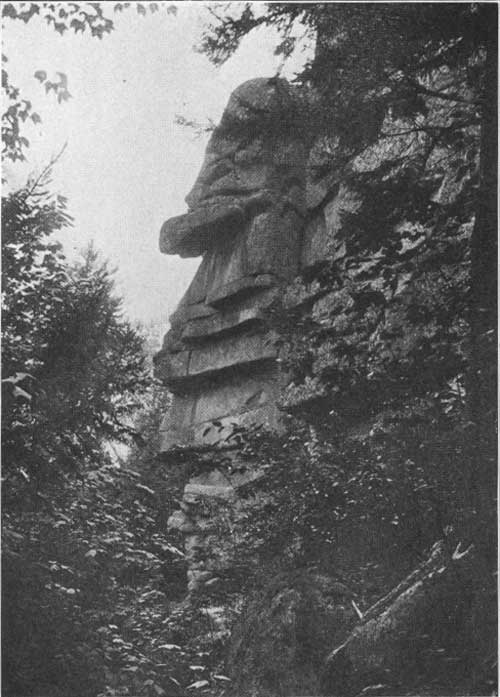

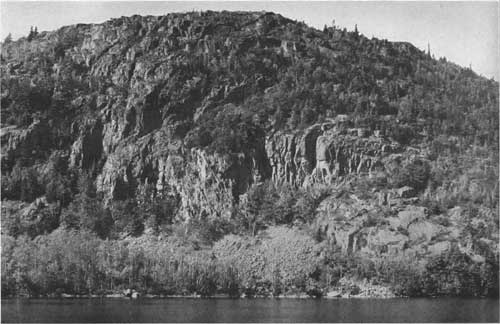

Geologically, the Monument, with its adjacent coastal rocks and headlands, forms a wonderful exhibit. Essentially, it is a bold and rugged group of granite peaks, immensely old though far less ancient than the primeval sea-laid rocks — hard, bent and twisted sands and clays — up through which they are thrust. These peaks, geologists say, united into a single mass, once bore an alpine height upon their shoulders which looked across wide valley lands toward a distant sea. Time beyond count laid bare the mountain base, which the slow southward grinding of the ice-sheet later trenched into a dozen deeply isolated peaks. Between them, hollows, deeper than the present level of the sea in places, now contain a number of beautiful fresh-water lakes and one magnificent fjord which nearly cuts the island into two. Finally, owing to a general subsidence along the coast, the sea swept inland, flooding round the ice-eroded remnant of the ancient mountain to form the largest rock-built island on the Atlantic shore from the St. Lawrence southward, and its highest elevation.

|

| ANCIENT SEA CLIFF ON THE CADILLAC PATH |

|

| NEW SEA CLIFF BEING FORMED BELOW THE OLD ONE |

In places on the island's southern shore, the granite comes down to the ocean front, forming the boldest headlands and thrusting out to meet the sea's attack the grandest storm-swept rocks upon our coast; in other places, the enclosing sedimentary rocks, hardened by the enormous heat and pressure caused by the granitic upburst, oppose the ocean with dark, furrowed cliffs of different character but equally magnificent, in shine or storm.

The whole Acadian region of eastern Maine, which the Sieur de Monts National Monument represents with rare completeness in a single tract of concentrated interest, is rich in delightful features, in forests, lakes and streams, and the wild life of every kind — plant, animal and fish — that haunts them. Its value as a vast recreative area for the whole nation to the eastward of the Rockies is even yet but little realized, although from the first opening of the fishing season in the spring to the close of hunting in the fall an immense tide of recreative travel streams continually through it.

The new National Monument, and future Park as it will doubtless be, lies — with all the added beauty of the ocean and interest of historic association — close beside the main entrance to this region, where the Penobscot mingles its fresh water with the sea. From the Monument, delightful trips by train, by boat, by motor, may be made on every side — up and down the coast; to New Brunswick, Cape Breton and Nova Scotia; or to the magnificent lake and forest regions of the interior. And to it, one may come, as to no other national park area on the continent, by boat as well as train or motor.

The chapter of world history which the Sieur de Monts National Monument commemorates, that of the first founding of Acadia, in 1604 — half a generation before the landing of the Pilgrim Fathers on the Massachusetts shore, and of the long French occupation of the Acadian region, extending from the Kennebec to Cape Breton, which followed it, is full of human interest as told in the pages of Champlain and Lescarbot in quaint old French, and by numerous later writers.

|

| BEECH CLIFF, FROM ECHO LAKE |

De Monts, a Huguenot of noble family in southwestern France, came out commissioned by Henry IV — Henry of Navarre — to occupy for France, and colonize, "the lands and territory called Acadia," extending, as it was then defined, from the 40th to the 46th degrees of latitude — those approximately of Philadelphia and Montreal to-day; to establish friendly trade relations with its natives; to explore its coasts and rivers; to govern it, and represent in it and on its seas the person of the King; and to bring its people, "barbarous, and without faith in God," into knowledge and practice of the Christian religion.

It was a great adventure, largely conceived and bravely carried out. De Monts planted the fleur-de-lis on the American shore, and for more than a century and a half it stayed there. That it is not floating there to-day is due to forces greater than national, to the growth of the democratic spirit and democratic principles of government in the English colonies, which gave them an inherent power that mounted like a rising tide till it possessed and overflowed their continent, and is to-day profoundly influencing the world.

De Monts himself, to say a word of him, was sprung from one of the most ancient families in France, distinguished in arms and military employments from the time of the First Crusade, when four brothers out of six journeyed "beyond the Sea" and two remained there — killed in the storming of Jerusalem. True to the family traditions, his father, Jean de Monts, baron of Cabrairolles in Languedoc, near Beziers, served in the army "from his earliest youth," was successively Ensign or standard-bearer, Lieutenant, Captain of Arquebusiers, and finally "Mestre de Camp" in 1586, with five hundred standard-bearers under him.

|

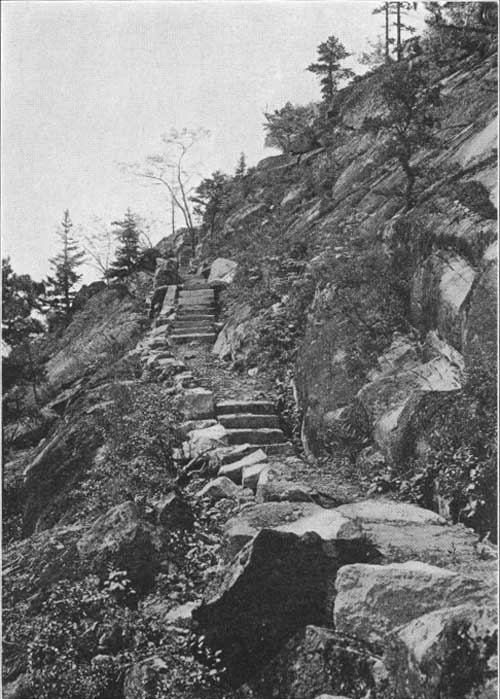

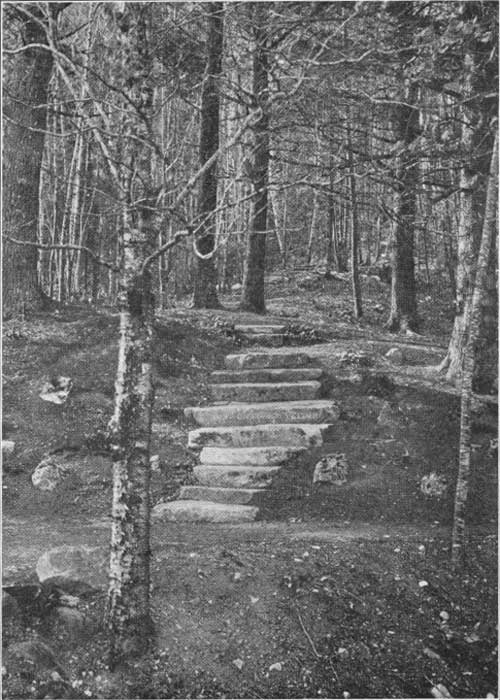

| SUMMIT PATH ON DRY MOUNTAIN |

|

| ENTRANCE TO KURT DIEDRICH'S CLIMB |

A Huguenot, he fought under Coligny in the defeat of Moncontour, then under Henry IV in the victories of Coutras and Ivry. He took part afterward in the capture of St. Denis and was wounded — for the second time severely — at the siege of Eperney, in 1592, dying two years later of his wounds. He was a typical soldier of his time and station one of those of whom Sismondi wrote: "The King (Henry IV) counted in his cavalry five thousand men of birth (gentilshommes) whose courage was sustained by a personal sense of honor, and who were superior to all other cavalry."

He married, on the 20th day of May, 1572, Delphine de Latenay, daughter of the noble Antoine, "ancien Capitaine," and of Marguerite de la Mairie. His oldest son, Jean, succeeded him as baron of Cabrairolles. Pierre, his second son, who came out to America, was seigneur of Guast and governor of Pons, one of the Huguenot places of security established by Henry IV, who, Champlain tells us, had "great confidence in him for his fidelity and the good services he had rendered him in the (recent) wars." And governor of Pons he still remains, apparently, when we catch our last glimpse of him in Champlain's pages, after Henry's death, though the tide had then set strongly against the Huguenots, and Pons was presently to be dismantled of its protecting walls by Henry's son, Louis XIII.

Pons itself, its relation to the Huguenots and de Monts apart, is an interesting old city of the feudal times whose powerful lords, the Sires de Pons, were sovereign princes in their region, descended from the dukes of Aquitaine. They made war, signed treaties, and received the King of France as "cousin," claiming the sword he wore that day whenever they paid homage to him, which they did in full armor with their vizors down. Their castle was stormed by Richard Coeur de Lion in 1179, and was surged around successively by French and English in the wars of Aquitaine.

To-day the place is an attractive city still, with picturesque ruins of the old chateau and later buildings of the 15th and 16th centuries, now used as a Hotel de Ville, which were de Monts' official residence no doubt when not across the sea.

|

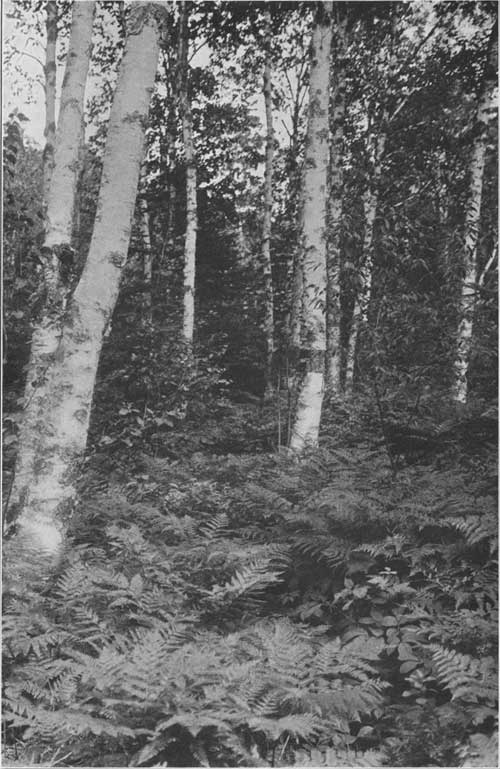

| BIRCH WOODS AND FERNS UPON A GRANITE UPLAND |

Delightful gardens, overgrown with roses, occupy in part the ancient castle site, with a stern old 12th century "keep" beside them, while the castle chapel, of a later date, opens through a noble romanesque portal onto a lower garden. A clear river flows beneath, from whose vanished bridge of Roman empire date, the early city drew its name: Pons or "Bridge." It is an ancient land throughout, of ruins and rich pasturages and productive vineyards, to whose western boundary come the breezes, the salt air and breaking surf of the Atlantic, and from whose shore the waves stretch off unbrokenly toward America and the Acadian coasts.

De Monts brought out to America with him, as lieutenant and cartographer, Samuel Champlain — his chronicler and fast friend thereafter — who, older than he by half a dozen years, was born in the little salt-gathering and exporting town of Brouage on the Bay of Biscay shore, not far from Pons and in a district subject to its lords. Near by was the mouth of the Charente — declared by Henry IV to be "the finest stream in the Kingdom" — with the ancient city of Saintes not far above, the capital of the Gallic Santones whose name it has brought down to us from Caesar's time.

Of Brouage, an antiquarian neighbor of it wrote three quarters of a century ago: "On a plain that the waves covered twice a day, and along the border of a canal which brought into its midst the highway of the ocean, salt evaporated from the sea was gathered and the vessels which came to carry it away left behind upon the bank the stones and gravel brought for ballast. Little by little a mound, not over 80 paces long, rose above the level of the marshland and on it there settled a colony of salters, fishermen and sailors. This was the origin of Brouage, later made by Richelieu one of the naval strongholds of the west and then depopulated by deadly exhalations from the marshes till now grass grows in the courts of its abandoned houses and trees rise among their ruins, spreading over them branches twisted by the ocean gales."

|

| THE SPRING HEATH — FROM THE EMERY PATH |

In 1568 — the year after Champlain was born — Brouage was seized and held for the Sire de Pons, who took the side of the Catholic party in the Civil War, although Saintonge itself was strongly Huguenot. Two years later — when Champlain was three years old — it was besieged and taken by the Huguenots, who held it then for half a dozen years, when it was again besieged by the Catholics, under the duke of Mayenne, and taken after months of resolute defence — the Huguenots, exhausted by privation, capitulating but marching out with arms and baggage, with drums beating and flags flying.

Such were the times and scenes amongst which Champlain grew up, and such, with the sea, the influences which took part in shaping him, but the influence of the sea was strongest; of that he writes, in the dedication of his book to the Queen-mother in 1613; "Among all most excellent and useful arts, that of navigating has always seemed to me to hold first place. For so much the more that it is hazardous, and accompanied by a thousand wrecks and perils, so much the more is it esteemed beyond others, being in no way suited to those who lack courage or self-confidence. This art it is that from my earliest youth has drawn me to itself, and led me to expose myself during nearly my whole life to the impetuous waves of the ocean."

Sailing from de Monts' first colony at the mouth of the St. Croix — our present national boundary — to explore the westward coast, Champlain made his first landing within this country's limits on Mount Desert Island, close to Bar Harbor probably, on its seaward side — wherever he first found safe beaching or good mooring for his damaged boat, stove on a hidden rock, he says, on entering Frenchman's Bay.

Champlain describes the mountains of the Monument as he saw them then, with deep, dividing gorges and bare rocky summits, and named the island from them, giving it, in a French form, the name which it still bears, the "Isle des Monts deserts."

|

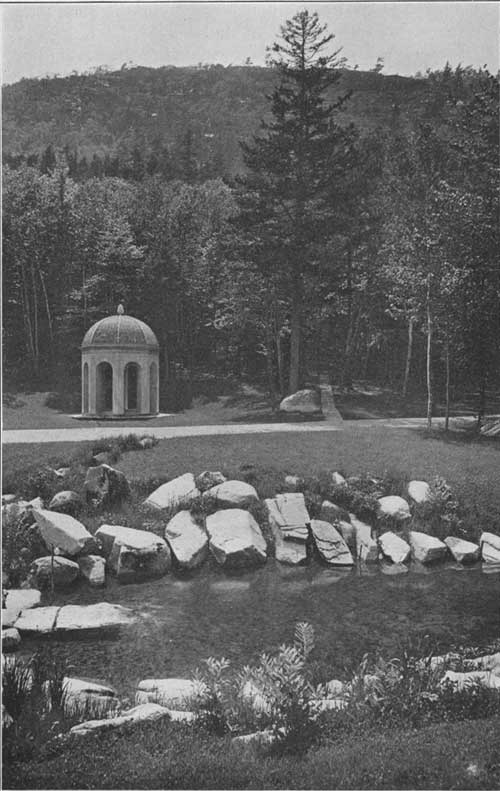

| SIEUR DE MONTS SPRING, THE ENTRANCE TO THE EMERY PATH, AND THE SWEET WATERS OF ACADIA — A MEMORIAL TO FRANCE |

|

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

sieur_de_monts/17/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 03-Dec-2009