|

ACADIA

The Sieur de Monts National Monument and its Historical Associations Sieur de Monts Publications XVII |

|

The Desert and the Wilderness shall rejoyce, and the waste ground be glad and flourish as the rose.

—Isaiah xxxv: I.

1583 Edition.

GARDEN APPROACHES TO THE NATIONAL MONUMENT

Mount Desert Island is remarkable for the vigor with which the hardy herbaceous plants that make the beauty and delight of northern gardens grow in favorable locations on it, and for their brilliant bloom. There, too, bloom follows bloom unbrokenly from spring to fall, keeping fresh the sense with constant change.

To establish in connection with the national park — using the word, as elsewhere in this paper, in its popular sense — a splendid permanent exhibit of these hardy plants, gathered for their beauty's sake from the whole temperate world, has been from the first, like the wild gardens and the wild life sanctuaries intended in the park itself, an essential feature of the plan from which the park resulted.

|

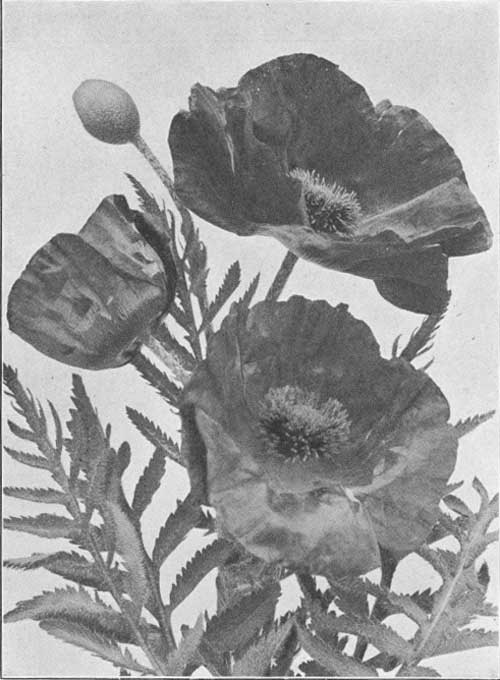

| ORIENTAL POPPY |

|

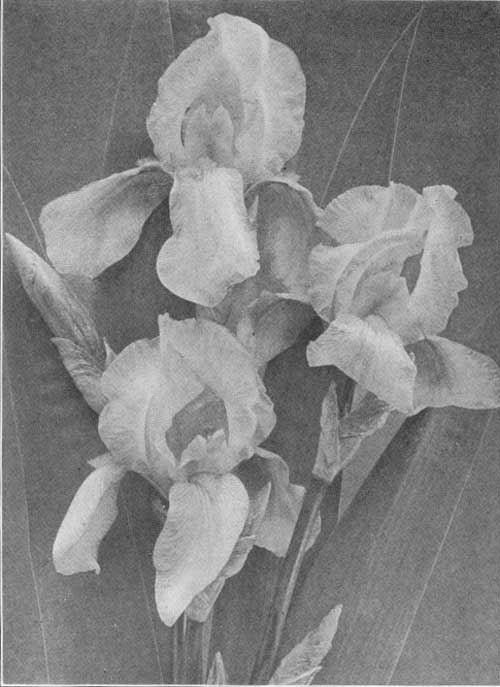

| FLORENTINE IRIS |

Nothing could be devised that would be more useful in furthering the development of a true art of gardening and landscape gardening in this country than such an opportunity to observe and study at their best the hardy plant materials which it must use. And nowhere else upon the Continent could a wider or more representative public be found to appreciate and profit by it than comes each summer to the Island a public that will come henceforth in constantly increasing numbers as the park, with its great waiting gifts of interest and beauty, is developed in accordance with the broadly formulated plans of the Secretary of the Interior and National Park Service.

With this in view, an opportunity for such a hardy plant exhibit in the form of garden walks extending from the park, which occupies the Island's mountain range, towards Bar Harbor, its most general and famous point of entrance, has been secured, and plans for it are being now worked out.

Two of the boldest mountain groups upon the Island bring the park within easy walking distance from the town. The eastern of these is that of Newport and Picket Mountains; the western, that of Dry Mountain and the Kebos. Against them both, facing abruptly to the north and east, the thrust of the arrested Ice Sheet in the Glacial period, as its huge mass moved slowly seaward past them, must have been tremendous.

|

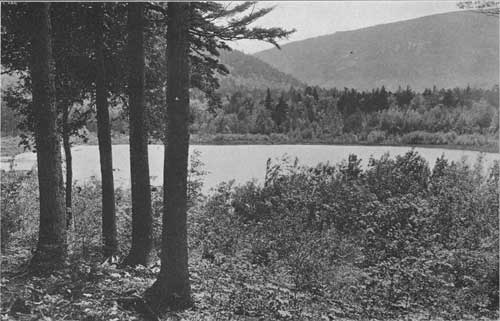

| BEAVERDAM POOL. A BIRD AND PLANT SANCTUARY ON THE WILD GARDENS PATH |

Evidence of it is not only visible in their rugged cliffs and precipices but in two deep basins ground out from the ancient Cambrian rock adjoining them.

One of these, Beaverdam Pool, lies at the foot of Newport mountain; the other, the Spring Heath — once a considerable lake but now completely filled with glacial clays and gravel peat and granite sands — reaches broadly out towards Bar Harbor from the eastern foot of Dry Mountain, forming a splendid exhibit of one of the most characteristic features of the north.

Portions of primeval forest, with massive trunks of ancient yellow birch and hemlock, border still these basins on their side towards the mountain; both make superb approaches to the Monument; and both are rich naturally in soil and water, in bird life and in plant life.

The one under Newport Mountain, with its brook valley reaching to the public road, has been already deeded to The Wild Gardens of Acadia for a plant and bird sanctuary; the one beneath Dry Mountain, acquired by the Sieur de Monts Spring Company for protection of its waters and for its scenic beauty, has been placed beneath the same control, and offered freely to the Government to use as though its own in its approaches and as a water source.

The Heath basin especially is remarkable for a succession of deep-seated springs that rise apparently from a line of fracture between the granite and the more ancient sea-laid rock it shattered as it rose. Singularly pure, unvarying in temperature or volume, and brought down probably from far away by seaward tilting of an ancient coastal plain they make, with their free gift of water to the passer-by, a unique, delightful feature in connection with the climbs that start or end along this base.

|

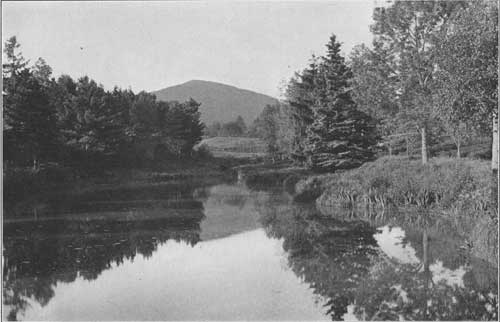

| COMPASS HARBOR POND. AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE WILD GARDENS PATH TO NEWPORT MOUNTAIN |

These basins, of the Spring and Pool, with their interesting native life, their wild flowers, trees and ferns and the wild background of the mountains, are natural wild garden areas, and so should stay. But leading to them three hardy garden walks are planned, approaches to the Monument. The one upon the bay, or eastward, side enters from the Old Post Road at Compass Harbor Pond, in the midst of Iris and other hardy gardens, and follows up Compass Harbor Brook through the ravine which it has cut from deep deposits of the Glacial period until the latter loses itself in the upland which divides this watershed from that of the Wild Gardens' basin under Newport Mountain.

This land, from Compass Harbor Pond till the divide is reached, has formed part till now, when given for the path, of the Mount Desert Nurseries' hardy gardens, and the beauty of the flowers which they have grown upon it, familiar to all who have visited the Island during the last twenty years, is a good earnest for the future, establishing, as do the many private gardens on the Island now, the remarkable possibilities of the soil and climate for such an exhibition.

Much work has been already done upon this path, which is the result of a long studied plan. The pond from which it starts is itself a natural water garden, around whose edge the native flags and cardinal flowers and superbum lilies mingle delightfully with English meadow-sweets, purple loosestrife and Siberian irises, while in its water the fragrant native pond lilies grow along with hardy species from abroad. Above, in the ravine, picturesquely wooded, moist and shady, ferns and all kinds of shelter-loving plants grow wonderfully, while over the upland which succeeds it an apple-shaded walk, a dozen feet in width between alternately-placed trees, leads on to a grove of native thorns which marks the entrance into the Wild Gardens' tract beneath the mountain.

Here, along this upland portion of the walk — sheltered from the wind by shrubbery plantations — the beautiful old hardy plants of English and Colonial gardens — monkshoods, peonies and irises, larkspurs, phloxes, lilies, starworts, globe flowers, and a host of others — with their new companions can be grown in the deep soil with little care. Many of them, like the day lilies and the Solomon's seal, the lily of the valley and the peach-leaved bell-flower, become completely naturalized and often hold their own successfully against invading native plants.

|

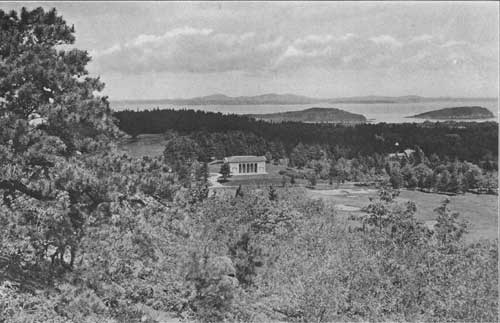

| THE BUILDING OF ARTS, THE GOLF LINKS, BAR ISLAND AND THE UPPER BAY, FFROM KEBO MOUNTAIN |

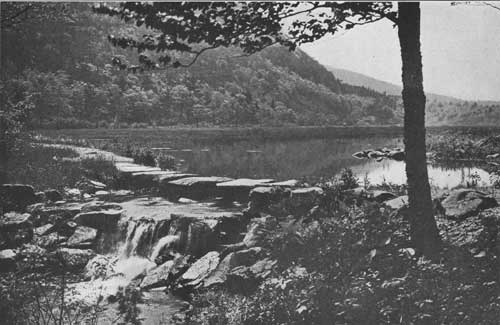

A mile to the west of this, another path — named in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Morris K. Jesup of New York, to whom Bar Harbor owes its beautiful Public Library and New York City its magnificent Natural History Museum's great endowment — leads from the neighborhood of the Building of Arts, placed directly facing the nearer mountains of the Monument in one of the most beautiful situations in the world, down past the golf links with a fifty-foot strip reserved along its side for hardy garden planting; then drops to the level of the sheltered heath, which it crosses presently — shaded by maple woods — and passes on, skirting the Delano Wild Gardens and the mountain base, to meet the Kane Path and the entrance to Kurt Diederich's Climb at the outlet of the Tarn. This path, until the heath is reached, lies over cultivated farmland of an earlier time, with a deep soil and south exposure, and there is no better spot upon the Island for planting of the kind intended, nor a course more interesting.

Between these other two a third approach — the Cadillac — is planned, starting from the Bar Harbor Athletic Field and Park, where the Government office is, and following up the brook that comes down to it from the mountains and the Spring. Along this also remarkable opportunities exist for arboretum and experimental planting, while the wild fern and woodland gardens, succeeding to the open heath, which it will enter as it nears the Spring, show under singularly favorable conditions the range and beauty of the native flora.

The plan for these approaches has been adopted only after long consideration and study of the plants intended to be shown, as well as of the landscape opportunity and soil conditions. It has received the warm approval, not only of the Secretary of the Interior and National Park Service but, of architects and gardeners and botanists of international authority and reputation.

|

| SIEUR DE MONTS TARN AND THE STEPPING STONES ACROSS ITS BROOK — FROM THE JESUP PATH |

Among them all, none has said a better word of hopefulness and encouragement regarding it than the writer of the letter — written in the earlier stages of the undertaking — with which this paper closes, Mr. C. Grant LaFarge of New York, a director of the American Institute of Architects, trustee and secretary of the American Academy at Rome, an architect of wide experience who has made a lifelong study also of our native flora and these garden plants.

GEORGE B. DORR.

Dear George:— The papers which you have asked me to examine, setting forth the project for developing a wild-life sanctuary and tree and plant exhibit and experiment station on Mount Desert Island, seem to me to describe a plan of comprehensive and striking interest. You ask me to tell you what I think of it. It appeals to me on so many sides that I can hardly deal with them all. As one long concerned with the question of preserving our native fauna in the only effective ways, such as game refuges and laws protecting migratory species, there is much I should like to say on this phase of the scheme as well as on its splendid aspect as a permanent great natural pleasure ground for many people. But these I must pass by to emphasize a specific point which strikes me forcibly, in view of my professional convictions.

Our community is aware but dimly, and in spots, of the tremendous strides being made in the art of architecture in America. Only those who, with open minds and trained eyes, contrast the body of our performance with its current equivalent in the Old World can appreciate it, and realize that it is cause, not for boasting but, for ardent hope and constantly greater effort. Many forces are at work, among them none stronger than the rapid and sure elevation and increase of our educational methods.

Along with our architectural advance must go that of the sister art of landscape design. There is no need for me to point out to you the intimacy of the alliance or the urgent necessity that equipment for the practice of the latter be, both theoretically and practically, of the fullest.

No constructive art can achieve its full development while those who practice it think in terms of its expression upon paper, and not in terms of the materials they have to use. There is only one way to gain the power to use these materials; that is, to have a close and comprehensive personal acquaintance with them. The more we survey the great triumphs of landscape art in the Old World, the clearer it becomes to us that those who designed and built and planted them worked with knowledge and in sympathetic understanding of the natural surroundings and resources, the native flora of the region and the trees and plants that could be grown in it successfully; that they were the very antithesis of paper performers, inspired by hazy views derived from the perusal of seductive catalogues.

I have an invincible belief in our need for the completest study of past examples. I shall not rest until we have added a Fellowship in Landscape Design to our American Academy in Rome. But I also am sure that the men who are to do great work in this country — and our vision hardly tells us yet how marvellous it may be — must know, to their fingertips, what this country offers of trees and shrubs and flowers and all growing things, and what may be done with them. When they know this, and use their knowledge, we shall have American gardens. To acquire this knowledge under present conditions is well-nigh impossible. The country is too vast; its flora too scattered. Even the most superb examples of wild growth are but stimulating suggestions, not made available by opportunity for close study and by certainty of what transplanting, cultivation, care and breeding will accomplish.

Your plan offers all this. If you succeed with it, I see all those who would equip themselves with what their art demands of them flocking to it from all quarters of the country. It would be a godsend, not only to those who live in approximately similar regions — there is none just like it — but to those others whose lives are cast in far less interesting places, of dull topography and limited flora. I can think of no one thing that could be done in America, more greatly to contribute to and to advance the art and the practice of American landscape design. Good luck to you.

Sincerely yours,

(Signed) C. GRANT LAFARGEJanuary 22, 1914.

|

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

sieur_de_monts/17/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 03-Dec-2009