|

FREDERICKSBURG FINALLY TARGETED

Stymied again, Burnside realized that he could not now make an

uncontested crossing anywhere, so he decided to bridge the river where the

enemy would least expect it—right in front of the city. Despite

Burnside's warning to evacuate the civilian population, Lee had

expressed doubt that he would ever strike there, or that he would try to

lay his pontoons anywhere between there and Port Royal because the banks

were so difficult. In fact, Lee anticipated the very plan Lincoln had

proposed, with Burnside landing at Port Royal under the protection of

navy gunboats and marching to cut the Confederates off at Bowling Green

while Banks's army (which Lee had learned of) struck up one of the

rivers at Lee's back.

Jackson's earthworks at Skinker's Neck convinced Burnside that Lee had

divided his army between there and Fredericksburg, and he supposed he

might throw down his bridges quickly, step between the two halves, and

defeat the enemy in detail. At the least, he could hope to confront

Longstreet's corps before Jackson arrived to reinforce him.

|

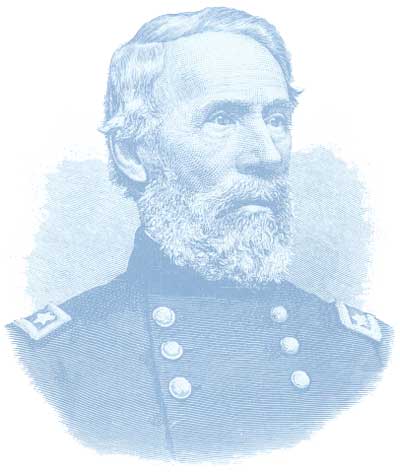

EDWIN V. SUMNER (BL)

|

Burnside's eldest and most devoted lieutenant, General Sumner, had

proposed a radical plan to the commanding general. Citing the firepower

the Confederates could converge on the bridgeheads from the city

waterfront, Sumner thought the entire army could more easily cross on

the plain below town if enough artillery were brought up to support it.

Then Burnside could march around Lee's right flank by the main road,

abandoning his own line of supply and forcing Lee to fall back and

protect his. Fredericksburg might thus be taken with much less loss.

Sumner's design was a good one. He was not the only one to think of it,

and Burnside apparently considered it for a time, but eventually he

opted for a more complicated strategy that might not only keep Lee off

guard but impede his escape. He would divide his forces, crossing

Sumner's Right Grand Division into the city and Franklin's Left Grand

Division onto the plain downstream, while keeping Hooker's Center Grand

Division for a reserve. Franklin would hit the Confederate right at

Hamilton's Crossing, and Sumner would assail the heights beyond

Fredericksburg, forcing Longstreet to either stand and fight while

Franklin flanked him or to retreat in the face of a direct onslaught.

Not only would such an approach be more likely to dislodge Longstreet,

it might throw his corps into a rout and lead to its capture, either in

whole or part.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

BURNSIDE IS POISED TO CROSS THE RIVER: DECEMBER 10

Prior to crossing the river, Burnside masses his troops near

Fredericksburg. Sumner's grand division is camped closest to town, near

Falmouth; Franklin is three miles to the east, at White Oak Church;

while Hooker's troops are in reserve, near Stafford Court House. On the

Confederate side, Longstreet holds a seven-mile line stretching from the

Rappahannock River above Fredericksburg to Hamilton's Crossing, below

the town. Jackson's corps is scattered over a wide area between

Hamilton's Crossing and Port Royal, while Stuart's cavalry guards the

army's flanks.

|

Burnside issued preliminary orders outlining his plan on December 9, and that

evening General Sumner called his corps and division commanders together

to familiarize them with the details. Major General Darius N. Couch, in

charge of Sumner's Second Corps, said that most of the senior generals

doubted the army would be able to cross in front of Fredericksburg;

perhaps they shared Sumner's fear that forewarned Confederate infantry

and artillery could annihilate any troops who crossed on bridges there.

|

CHATHAM

Across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg, on the bluffs

overlooking the town, stands Chatham a plantation house built by William

Fitzhugh beginning in 1768. At the time of the Civil War the house was

owned by J. Horace Lacy, a major in the Confederate army.

Union troops occupied Chatham for the first time in April 1862, when

General Irvin McDowell set up headquarters at the house. McDowell

brought a corps of 30,000 men to Fredericksburg. He halted his command

at Fredericksburg for a month in order to bring up supplies, after which

he planned to march on Richmond. President Abraham Lincoln journeyed to

Fredericksburg to confer with McDowell about the proposed movement and

on May 23 dined with him at Chatham. That very day, Stonewall

Jackson's Confederates attacked Union troops in the Shenandoah

Valley and briefly threatened Washington, D.C. As a result of Jackson's

success, Lincoln ordered McDowell to forgo his march on Richmond and

take a portion of his command to the Valley instead. General Rufus King

took over command at Fredericksburg in McDowell's absence and moved into

Chatham.

|

CHATHAM: A WARTIME VIEW (USAMHI)

|

The next prominent figure to come to Chatham was General Ambrose

Burnside. The War Department summoned Burnside to Virginia in August to

reinforce Union troops defending Washington. While waiting for his

troops to debark at nearby Belle Plains, the genial, bewhiskered general

camped on Chatham's front lawn. While there, he received a visit from

his friend General George B. McClellan, whose troops, like Burnside's,

were then steaming north on ships to protect the threatened capital.

On September 17 McClellan defeated Lee at Antietam, and the

armies again drifted back to Virginia soil. Antietam was McClellan's

last battle. Annoyed by the general's hostile attitude and frustrated

by his unwillingness to bring Lee to battle, Lincoln ousted McClellan in

November 1862 and appointed Burnside to command the Army of the Potomac

in his place.

Burnside quickly took action. Within ten days after assuming command, he

had his army marching east, toward Fredericksburg—and disaster.

Leading the march was General Edwin V. Sumner, the 65-year-old

commander of Burnside's Right Grand Division. Sumner reached Falmouth,

opposite Fredericksburg, on November 17, but Burnside forbade him to

cross the river without pontoon bridges, which did not arrive for

another week. By then, Lee's army occupied the heights behind the

town.

For three weeks Burnside delayed, pondering his options. When he finally

tried to cross the river at Fredericksburg on December 11, Mississippi

riflemen barred the way. Burnside wrathfully shelled the town and in

the afternoon ferried troops across the water. The Mississippians held

their ground until sunset, then fell back to the main Confederate line

at Marye's Heights. By dark, Union engineers had bridged the river in

several places with pontoons.

On December 12, Sumner's Right Grand Division filed past Chatham on its

way to the bridges. The next day, with his army in place, Burnside

attacked. William B. Franklin assailed the southern end of the

Confederate line, while Sumner's men gallantly, but unsuccessfully,

tried to storm Marye's Heights. Forbidden by Burnside to cross the

river, Sumner watched the destruction of his command from Chatham's

second-story porch.

By the time the battle had ended, 1,200 Union soldiers were dead and

another 9,500 had been injured. Many of the wounded soldiers received

care at Chatham. Clara Barton assisted wounded soldiers at the house as

did poet Walt Whitman, whose brother George was numbered among the

casualties. For surgeons working in Chatham's north wing, amputation was

the order of the day. Surgeons tossed mangled limbs out the window, and

they landed at the foot of catalpa trees in the front yard. A huge pile

of limbs accumulated there—about a load for a one-horse cart,

Whitman noted. Patients who survived the ordeal were sent to general

hospitals in the North. Those who did not were wrapped in woolen

blankets and buried beneath Chatham's cold sod. At least three soldiers

remain buried on the grounds to this day; the rest have since been

interred at the Fredericksburg National Cemetery.

The Union army wintered in Stafford County after the Battle of

Fredericksburg. Union pickets guarding the river cut down Chatham's

trees and piled the wood in the downstairs fireplaces to keep warm. As

the trees disappeared, they tore paneling from the building's interior

for fuel and scrawled their names on its barren walls.

|

A NEW JERSEY SOLDIER MADE THIS SKETCH OF

CHATHAM WHILE CAMPED IN THE AREA. (CUMBERLAND COUNTY, NEW JERSEY,

HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

Meanwhile, the Army of the Potomac gained a new leader. In January 1863,

Joe Hooker replaced Ambrose Burnside as the army's commander. Hooker

led the army across the Rappahannock River above Fredericksburg in May

and engaged Lee at Chancellorsville. At the same time, General John

Sedgwick's Sixth Corps and John Gibbon's division of the Second Corps

crossed the river at Fredericksburg and menaced the Confederates from

the coast. Gibbon made his headquarters at Chatham—the last Union

general to do so.

Sedgwick successfully attacked the Confederates at

Marye's Heights, but later retreated across Scott's Ford when

confronted by Confederates at Salem Church. Gibbon (whose division had

remained in Fredericksburg) likewise withdrew, taking up the pontoons

behind him. Once again Chatham became a scene of cruel suffering, as

wounded soldiers—North and South alike—found care and shelter

within its walls. When space on the dirty floors gave out, tents were

erected on the grounds around the house.

By the time the war ended in 1865, Chatham was in desolation. The

house's elegant interior had become a ruin: its beautiful grounds, a

graveyard. The property languished until the 1920s when General and Mrs.

Daniel Devote restored the house to its former splendor. Chatham's last

owner, John Lee Pratt, donated the house to the National Park Service in

1975. Today it is the headquarters for Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania

County National Military Park.

|

The next afternoon, December 10, Burnside chaired his own conference at

the Lacy mansion, Chatham, with Sumner and the chief officers of the

Second, Third, and Ninth corps. He said he planned to begin building the

bridges before dawn the following day. Debate over the news rose

immediately and lasted for hours. Burnside's subordinates apparently

resisted him, challenging the wisdom of bridging the river there. Many

of the men on Sumner's staff suspected that any crossing before the city

would be attended with great slaughter, but the meeting appears to have

ended with everyone agreeing to give the operation his best effort. From

there Burnside rode away to brief Hooker and Franklin.

|

|