|

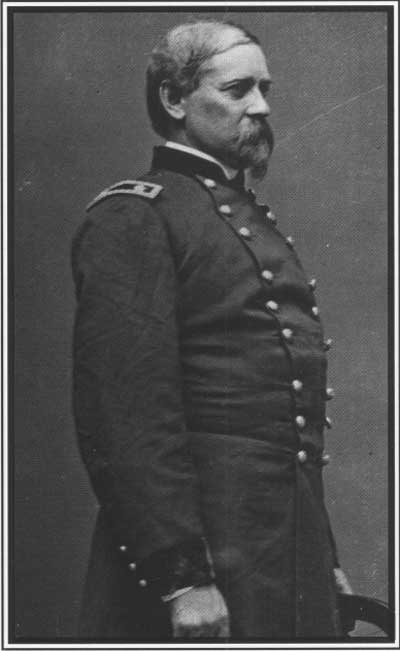

The officer commanding the Union force (which also included cavalry)

was Major General William F. "Baldy" Smith, who was something of a

martinet. Smith and some of his men had been temporarily transferred to

the Army of the Potomac in early June and saw service at Cold Harbor.

There, on June 3, he had seen firsthand the folly of attacking

well-manned earthworks. Because of that experience, his march to

Petersburg from Bermuda Hundred and City Point was very slow and very

cautious. Ironically, his combined force of approximately 15,500 men

faced only 2,200 Confederates defending Petersburg, but they were posted

behind the forbidding Dimmock fortifications. This disparity of forces

was a critical problem for Beauregard. So well had Grant masked the real

objective of his march to the James that Robert E. Lee held off

reinforcing Petersburg, fearing for Richmond's safety. Determined to

defend the Cockade City, Beauregard made a courageous decision to

abandon his Bermuda Hundred lines and hurried these troops south even as

Smith's men approached.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

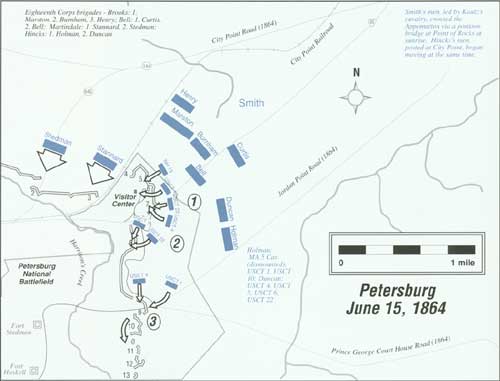

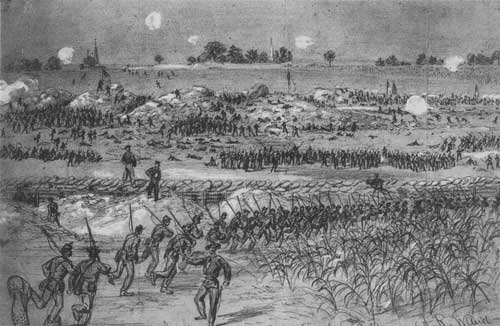

ENEMY AT THE GATES

After a cautious approach that occupied most of the morning and

a series of careful reconnaissances that lasted throughout the

afternoon, Union Eighteenth Corps commander Maj. Gen. William F. "Baldy"

Smith assaults the formidable Dimmock Line at 7 P.M. His widely

dispersed attack formations overrun the thirty manned Confederate lines

and enjoy great success until darkness and Smith's hesitation bring the

operation to a close.

|

Smith's advance was stalled for several hours by stubborn Rebel

opposition at an outlying post on Baylor's Farm. Once that was cleared,

he spent more time scouting the enemy lines and refining his plans. When

he informed his officers that he intended to attack at 4:00 P.M., he

learned that his artillery chief, assuming there would be no further

action this late in the day, had sent all of his horses to the rear to

be watered. It wasn't until 7:00 P.M., thirteen hours after he first

made contact at Baylor's Farm, that Smith's assault began. He had

correctly divined Beauregard's critical lack of manpower, so, instead

of attacking en masse, he chose a more dispersed skirmishing formation

that provided few targets to the Rebel gunners.

White troops from Colonel Louis Bell's brigade overran Battery 5 on

the Dimmock Line, while others surrounded neighboring Battery 6. "Here

we had to fight hard," wrote a New York soldier. Some of the troops in

Brigadier General Edward W. Hincks's all-black division assisted in

capturing Battery 6, while others from that unit rolled the line up to

the south, taking possession of Batteries 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11. Said one

of the white officers in that brigade, "I am now prepared to say that I

never. .. saw troops fight better, more bravely, and with more

determination." On the other flank of this line,

Rebel Batteries 3 and 4 also changed hands. In this brilliant

assault, "Baldy" Smith's men had captured more than a mile of the

Dimmock Line. As Beauregard later admitted, "Petersburg at that hour

was clearly at the mercy of the Federal commander."

|

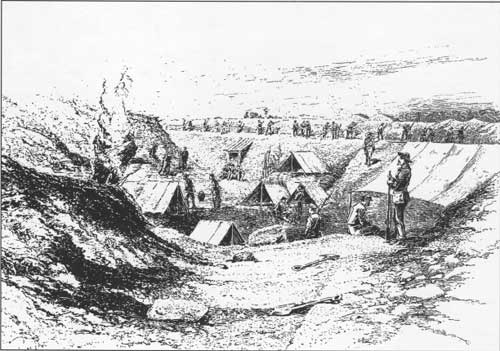

CONFEDERATE WORKS OF DIMMOCK LINE CAPTURED ON JUNE 15, 1864. (LC)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM F. SMITH (NA)

|

But Smith was feeling anything but sanguine. "I .. knew that

[Confederate] reinforcements had been rushing in to Petersburg," he

reported. "I knew nothing of the country in front. My white troops were

exhausted.... My colored troops... could barely be kept in order." Smith

decided to risk no more and ordered his men to hold their ground. For

the soldiers who had seen the Rebels flee and who now stood within sight

of Petersburg, it was an unbelievable decision. "I swore all night," one

of them recalled. "I kicked and condemned every general there was in the

army for the blunder I saw they were making."

Even the arrival at 9:00 P.M. of the lead elements of the Second

Corps did not convince Smith to change his mind. No night attack was

considered; instead the newly arriving units were sent to replace the

black troops, and to prepare for an assault early the next day, June

16.

P.G.T. Beauregard was at his best when the outlook was hopeless.

Using the troops that were arriving from Bermuda Hundred, he patched

together a makeshift defensive position, anchored on still unoccupied

sections of the original Dimmock fortifications, which were now

connected by a line his men had feverishly scraped out behind Harrison's

Creek. Beauregard was aided in his efforts by the continuing ineptitude

of the Union high command. Smith relinquished responsibility to Major

General Winfield S. Hancock of the Second Corps, who was suffering from

an unhealed wound he had received at Gettysburg. Hancock and Smith

failed to combine their forces and the Federals, on June 16, launched a

succession of piecemeal attacks, all of which were repulsed.

On the morning of June 17, Beauregard had in his trenches virtually

all of the troops immediately available to him. His lines were struck at

dawn in a series of well-planned attacks by the Federals, who had been

steadily reinforced by more units from the Army of the Potomac. Two

brigades from the Ninth Corps took advantage of a deep ravine and a gap

in the Confederate lines to capture a section of Beauregard's position

near the Shand house. Follow-up actions later in the day were less

successful, but by nightfall it was clear that portions of the

Petersburg line had been compromised by the Federal advances. June 18

promised to be a day of decision, with the overwhelming weight of the

Union legions certain to swamp Beauregard's thinly spread units.

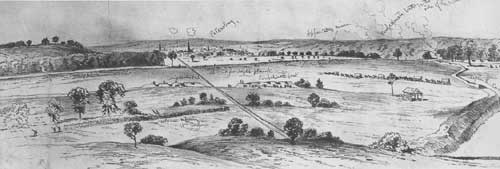

|

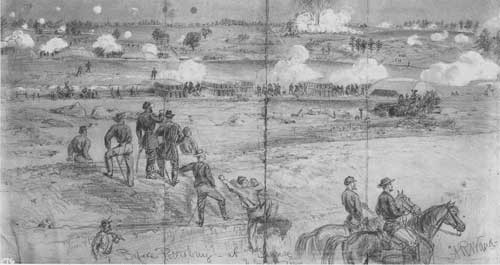

VIEW OF THE LINES AT PETERSBURG ON JUNE 18. ILLUSTRATION BY EDWIN FORBES. (LC)

|

Beauregard once again rose to the moment. In the early morning hours

of June 18, he ordered a secret withdrawal to a new defensive line much

closer to town. When the confident Yankees sprang to the attack at dawn,

they found empty trenches. There was confusion and hesitation while

reports traveled up the chain of command and scouts pushed out to locate

the new Rebel positions. Through this unexpected maneuver, Beauregard

managed to throw the Federal military machine out of sync. Once more,

brigades and regiments lunged forward in a haphazard fashion, allowing

the outnumbered defenders to concentrate to meet each in turn

successfully. Attempts to coordinate a united assault made by

General Meade (who had been placed in overall command in the field on

June 16) fell apart, and hundreds of Union soldiers paid the price.

In one action this day, nearly 900 men in the First Maine Heavy

Artillery charged across an open field near the Hare house, right into

the sights of Beauregard's waiting veterans. When the dazed survivors

reeled back after ten minutes in the open killing ground, 632 of their

comrades lay bleeding or dead on that field. "They were laid out in

squads and companies," recollected one horrified onlooker. As the

last column of Federals withdrew at the end of this day, the leading

elements of the Army of Northern Virginia entered the town. Lee, who

reached Petersburg at 11:00 A.M., now recognized that the focus of combat

had shifted here.

|

GENERAL P.G.T. BEAUREGARD (LC)

|

|

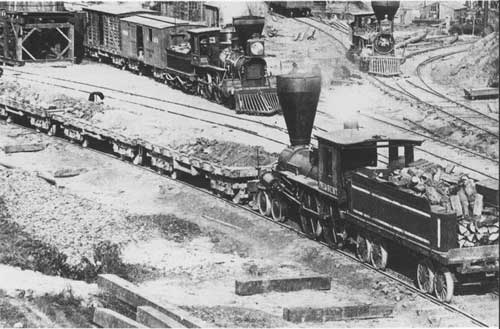

THE RAILROAD AT CITY POINT. (LC)

|

|

A. B. WAUD SKETCH OF THE FIRST CONNECTICUT HEAVY ARTILLERY TAKING

PART IN THE MID-JUNE 1864 ATTACK ON CONFEDERATE LINES. (LC)

|

Marching at the head of Lee's column was the Twelfth Virginia, which

included the Petersburg Rifles. Private George Bernard savored the

hometown welcome. "The great number of ladies that greeted us along the

streets made us feel more as though we were going to participate in some

festivity," he remembered.

Four days of desperate fighting had cost the Federal armies more than

10,000 casualties and the Confederates about 4,000. Grant had not taken

Petersburg and now faced a military siege. Lee had been forced into a

relatively static position where he had no choice but to stand and

defend Petersburg and Richmond. Ironically, Beauregard's victory lost

Lee any hope of regaining the tactical initiative.

Another result was that the Federals now had the second of five

railroads supplying Petersburg. Before the battle lines could harden

into formidable earthworks Grant moved to capture one more. On June 21,

the Second Corps, under the still ailing Hancock (who would soon be

temporarily replaced by Major General David Birney), supported by the

Sixth, moved south along the Federal line and spread along the Jerusalem

Plank Road. Scouting parties actually pushed west as far as the tracks

of the Weldon Railroad, and orders were issued for a full-scale advance

the next day.

This supply link was too important to surrender without a fight, so

when three divisions from the Second Corps moved out from the Jerusalem

Plank Road on June 22, two Confederate divisions were sent out from the

Petersburg entrenchments to intercept them. These Yankee units were once

considered the elite of the Army of the Potomac, but the fighting of May

and June had fallen especially heavily on this corps, which had lost so

many regimental officers and sergeants that its morale and efficiency

were poor. So when Rebel troops came screaming out of the woods, the

Second Corps, wrote Private Bernard in his diary, "were soon put on the

run."

|

THIS ILLUSTRATION BY EDWIN FORBES SHOWS BURNSIDES'S CORPS CHARGING THE

CONFEDERATES. (SCW)

|

The Union troops finally rallied along the Jerusalem Plank Road, but

2,400 were now casualties, with 1,700 prisoners. Emboldened by this

apparent weakness, Robert E. Lee planned a counterstroke to unhinge

Grant's line from the Appomattox River and shove it away from

Petersburg. Lee's army had also suffered appalling losses in the May

campaign, however, and he was no more adept at melding units from

separate armies (in this case, a division from Beauregard's command with

one from his own) than was Grant. The unsuccessful attack that took

place on June 24 merely added 300 names to Lee's casualty rolls.

Reviewing this action, Lee commented that there seemed "to have been

some misunderstanding as to the part each division was expected to have

performed."

In an operation that was part of Grant's larger plan, Major General

James H. Wilson set out from Petersburg on June 22 with two cavalry

divisions (about 5,000 troopers) with orders to wreck the railroad lines

west of the city. Wilson accomplished most of his task but was met by a

superior force on his return and defeated near Reams Station on June 29,

losing most of his wagons and allowing many of the slaves who had

escaped to join his column to be retaken.

|

THE 13", 17,000-POUND MORTAR KNOWN AS "THE DICTATOR." (NA)

|

The war against Petersburg's civilians began on June 16, when a

Massachusetts battery set its guns at maximum elevation, "fired the

first shells known to have been thrown into the city," and panicked some

of the noncombatants. A Virginia artillery man noted on June 20 that it

was "very distressing to see the poor women & children leaving." In

late July, a correspondent observed that the "houses, and even the woods

and fields, for miles around Petersburg are filled with women and

children and old men who have fled from their homes." Added a surgeon,

"What they live on their Heavenly father only knows."

Yet many others remained behind and learned to cope with the Union

siege artillery of every type and caliber that ranged the town. (The

most photogenic of them was a 13-inch mortar known as the "Dictator,"

which hurled its 200-pound shells up to two and a half miles.) A

Confederate cavalryman remarked that "it was really refreshing to see

ladies pass coolly along the streets as though nothing unusual was

transpiring while the 160-pound shells were howling like hawks of

perdition through the smoky air."

The spade now came into play as miles of entrenchments were dug. A

Connecticut chaplain remembered the deadly routine, "lying in the

trenches; eyeing the rebels; digging by moonlight; broiling in the sun;

shooting through a slit, shot at if a head is lifted." An Alabama Rebel

recalled that the "heat was excessive—there was no protection from

the rays of the sun; the trench was so narrow that two men could

scarcely pass abreast, and the fire of the enemy was without

intermission." On top of this, the men were tormented by swarms of

flies, lice, ticks, and chiggers and suffered from the lack of good

water near the front. Death sought them out in innumerable ways; from

sickness, accident, a sniper's bullet, or the burst of a mortar shell.

"This life in the trenches was awful—beyond description," a

Confederate officer declared.

The opposing trenches were especially close along the section of the

lines near the Taylor farm, where a Confederate redoubt known as

Elliott's Salient was just 400 feet from the Federal outposts. By

coincidence, these Yankees belonged to a Pennsylvania regiment recruited

in the Schuylkill County coal-mining district. The officer in command,

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants, got the idea to tunnel under the

enemy position and blast it with gunpowder. His immediate superior was

thinking along the same lines, and on June 24 they submitted their idea

to the man in charge of the Ninth Corps, Major General Ambrose

Burnside.

|

LIEUTENANT COLONEL HENRY PLEASANTS (BL)

|

Burnside had previously commanded the Army of the Potomac, and he was

on less than friendly terms with General Meade, who had serious

misgivings about the proposed operation. Nevertheless, not having any

better ideas, Meade allowed the tunneling to go forward, though his

headquarters staff provided no assistance and some obstruction to it.

Despite lacking adequate tools and missing some key mining equipment,

Pleasants and his men made remarkable progress. A way was found to

dispose of the excavated dirt so as not to arouse suspicion, shoring

timbers came from a nearby sawmill operated by the regiment, and tools

were improvised from what was on hand. Perhaps the most vexing problem

solved by Pleasants was the matter of ventilation. Fresh air was needed

at the tunnel face so Pleasants created a circulating system by heating

and expelling the bad air up a chimney shaft dug for that purpose and

using an eight-inch-square wooden duct to bring good air in along the

floor. The passageway the miners created had an average height of five

feet, with a four-and-a-half-foot-wide floor that tapered to two feet at

the top.

|

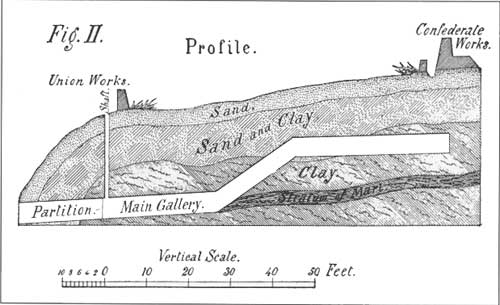

AN ILLUSTRATION OF THE MINE. (BL)

|

By July 17 the tunnel had reached a point directly beneath the

salient—a distance of 511 feet. Work was briefly halted while

examination was made to determine if there was any danger posed by

Confederate countermines.

Digging soon resumed, and a pair of lateral galleries were run

parallel to the enemy line. On July 27, the Pennsylvanians began to pack

the galleries with four tons of gunpowder.

Events elsewhere now influenced this operation. In mid-June Lee had

sent one of his army corps to the Shenandoah Valley hoping it could

distract and otherwise disrupt Federal plans. In a move partially

designed to prevent Lee from reinforcing this army, Grant, on July 26,

ordered the Second Corps of infantry and cavalry to the north side of

the James, crossing it near Deep Bottom. Lee responded by shifting

significant numbers of troops from Petersburg to that sector. The

Federal commanders on the north side (Hancock and Major General Philip

H. Sheridan) failed to break through, so by July 29 Grant looked for an

effort on Burnside's front.

While Pleasants's men had been digging, Burnside had been planning.

He had selected his yet untested all-black division to lead the assault,

and these men spent the hot weeks of July undergoing special training.

Burnside's design was for the troops to advance in three waves; the

first and second were to secure the trenches on either side of the

exploded mine, while the third would charge directly through the

gap to capture the high ground beyond. Then, in a July 28 meeting

with Meade, Burnside learned that the date for exploding his mine had

been set for July 30 and that he could not use his black troops as

intended. Meade did not believe that the untried units were up to the

task, and he worried about the political fallout should these regiments

take heavy losses. Deeply unsettled by Meade's decision, Burnside called

in the commanders of his three white divisions and had them draw lots.

The short straw went to his least capable division commander, Brigadier

General James H. Ledlie.

|

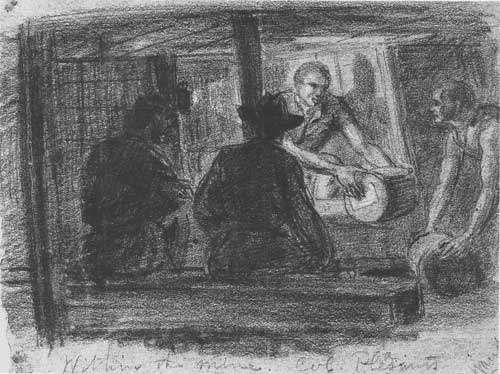

PLEASANTS SUPERVISING THE ARRIVAL OF POWDER. SKETCH BY A. R. WAUD.

(LC)

|

At 4:44 A.M. the four tons gunpowder went off in a cataclysmic

eruption. "The earth seemed to tremble," said an Alabama officer, "and

the next instant there was a report that seemed to deafen all

nature."

|

At 3:00 A.M., July 30, Lieutenant Colonel Pleasants entered the mine

and lit the fuse, which he estimated would burn thirty minutes. Everyone

waited in acute anticipation as the time passed with no explosion.

Finally, about 4:15 A.M., he sent two men into the tunnel to

investigate. They discovered that the fuse had failed at a splice; they

relit it and hurried back out to daylight. At 4:44 A.M., the four tons

of gunpowder went off in a cataclysmic eruption. "The earth seemed to

tremble," said an Alabama officer, "and the next instant there was a

report that seemed to deafen all nature." Where the redoubt had been was

now a steaming hole about 170 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 30 feet

deep.

The white troops, who had not been prepared to lead the assault, were

stunned and slow to recover. By the time the first waves were entering

the smoking crater, the equally shaken Confederate defenders were

beginning to react. Lacking a coherent plan, Ledlie's division failed to

secure its flanks and was unable to mount a drive to the crest. A second

white division went in on the heels of the first but was also unable to

generate enough momentum to break through. Rebel fire from the flanks

grew in intensity, even as the first of several counterattacks struck

the head of the Federal column. By the time the black troops were

committed it was too late. The white units had lost all cohesion; the

Confederates had sealed the penetration and were actively reducing the

pocket. The Crater became the scene of bitter hand-to-hand fighting, and

many of the black troops met a horrible fate. "But little quarter was

shown them," Private Bernard recalled. "My heart sickened at deeds I saw

done."

|

WAUD'S DRAWING OF THE EXPLOSION OF THE MINE UNDER THE

CONFEDERATE WORKS, JULY 30, 1864. (LC)

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE MINE

In one of the most remarkable military engineering feats of the Civil

War, Union troops (mostly Pennsylvania coal miners) dig a 500-foot

tunnel and explode four tons of gunpowder under the Confederate line.

The ensuing assault by Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's Ninth Corps

is a bloody fiasco. Black troops trained for the operation are replaced

at the last minute by untested white troops who do not know the plan.

Their failure to break the line and secure the high ground beyond,

coupled with fierce Confederate counterattacks, spells the doom of this

ambitious attempt to capture Petersburg.

|

Orders to withdraw were issued by midday, but for many it was too

late. Nearly 4,000 Federals were lost in the operation, while the

Confederates paid with 1,600 of their own to regain the position. In the

recriminations that followed, Burnside and Ledlie (who was likely drunk

throughout the action) were relieved of their commands, and three other

officers were censured. Of this operation U. S. Grant later reflected, "It was

the saddest affair I have witnessed in the war."

|

UNION ADVANCE INTO THE CRATER AFTER THE EXPLOSION OF THE

MINE, JULY 30, 1864. DRAWING BY A. R. WAUD. (LC)

|

|

CONFEDERATE TROOPS OCCUPY THE CRATER OF THE MINE AFTER THE

JULY 30 ATTACK. (LC)

|

|

|