|

Geological Survey Bulletin 1359

Geology and Mineral Resources of the Northern Part of the North Cascades National Park, Washington |

GEOLOGY

(continued)

GLACIATION

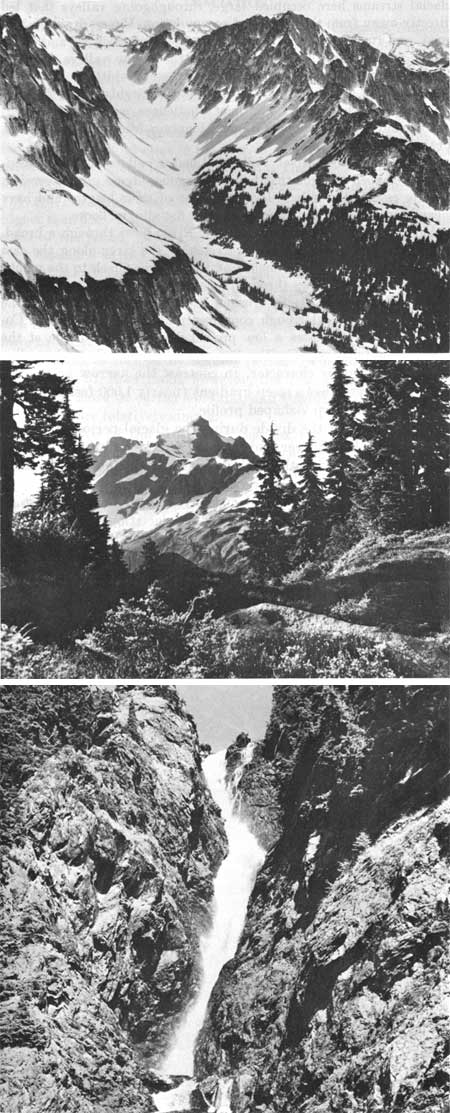

Glaciation in the northern part of the North Cascades National Park has produced remarkable scenic features, such as deep, steep-sided to vertical-walled U-shaped valleys (fig. 16A), jagged horns (fig. 16B), narrow arêtes, and spectacular waterfalls (fig. 16C) that cascade hundreds of feet into the valleys below.

|

| FIGURE 16.—Glacial features. A (top), U-shaped valley is formed along northwest-flowing tributary of Indian Creek. Indian Mountain lies to right of valley and a part of Red Face Mountain is to left. Small crescent-shaped lake in valley is Lake Reveille. B (middle), Mount Despair forms a jagged horn in the southern part of the area. C (bottom), Falls cascade down a narrow chute in phyllite just south of Berdeen Lake. |

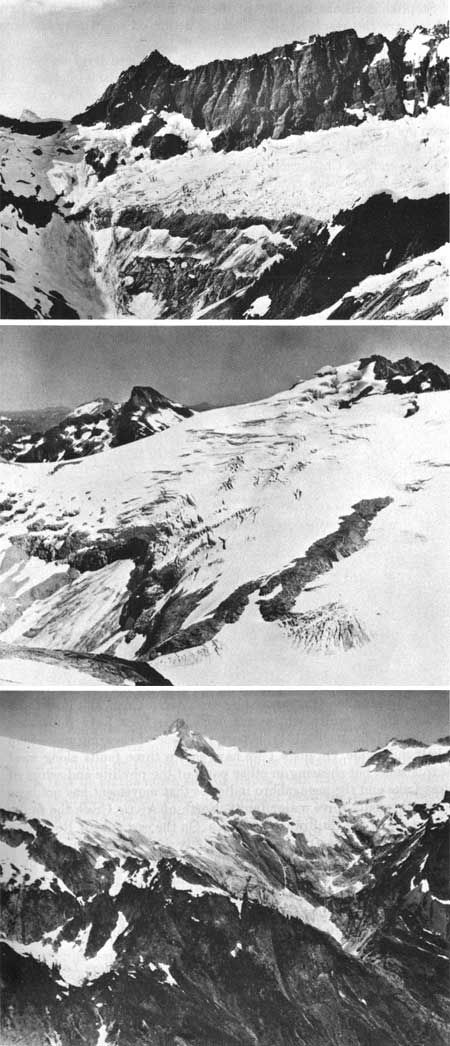

Although the large glaciers that produced these features are gone, many small glaciers (frontispiece) still cling to the high cirques. Of the more than 250 glaciers in the area, most are small, but several are more than 1 square mile in area (fig. 17). The largest glaciers are on Mount Shuksan (fig. 17C), Mount Challenger (fig. 17B), Bacon Peak (fig. 11), and Mount Redoubt, and smaller ones are on peaks and ridges higher than 6,500 feet. Most of the glaciers lie on the north or northeast sides of the peaks. These areas receive the greatest snow accumulation, inasmuch as they lie to the lee of the prevailing winds, and they receive the least sunlight. A notable exception is found on Mount Shuksan, where two of the mountain's largest glaciers, the Sulphide and Crystal Glaciers (fig. 17C), occur at a high elevation on its south side as a result of the heavy snowfall accumulation on extensive areas that have a relatively gentle gradient.

|

| FIGURE 17.—Glaciers. A (top), Eastern part of the East Nooksack Glacier at the head of the North Fork Nooksack River. Ridge above is Jagged Ridge. Rocks above glacier are phyllite; those below are granodiorite. B (middle), Numerous crevasses on the Challenger Glacier. Top of Mount Challenger is to the right, and Luna Peak is prominent horn in left background. C (bottom), Sulphide Glacier to the left and Crystal Glacier to the right are separated by a narrow rock septum on the south side of Mount Shuksan. |

Although glaciation has been intense throughout the North Cascades, its effects vary widely from place to place. East of Ross Lake geologic features formed by several periods of major glaciation are found. West of Ross Lake, however, the last major glaciation obliterated evidence of earlier episodes, and thus the nature and effects of glaciation are relatively simple.

The intensity of the erosion of the last major glaciation in the northern part of the North Cascades National Park is apparently the result of abundant ice and large runoff. At present, prevailing winds are from the west, and hence, the westernmost part of the Cascade Mountains gets the heaviest precipitation. Similarly, during the period of major glaciation, snowfall and the formation of glaciers were probably greatest in this area. The greatest thicknesses of ice formed along the major drainages, which were deepened and widened into broad U-shaped valleys (fig. 16A) by the great masses of ice moving down them. Although most of the tributaries of these large streams contained glaciers during the Pleistocene none of them were large enough to erode deep valleys, although sizable cirque basins were carved in many of them. Hence, the tributaries are now left hanging on the sides of the major valleys, whose bottoms they now reach through a series of falls or steep cascades (fig. 16C). The highest and one of the most beautiful of these falls, at the outlet of Green Lake on the north side of Bacon Peak, drops nearly 1,500 feet to Bacon Creek; many others have falls of several hundred feet. The glacial streams here occupied large, throughgoing valleys that led directly away from the centers of accumulation. Hence, drainage was good, and runoff was rapid. The combination of thick ice and rapid runoff was highly effective in carving the major valleys down to base level and in widening them to their present width.

Present-day drainage west of Ross Lake is roughly radial from an irregular area that centers on Mount Challenger, with secondary centers around Mount Redoubt, Hagan Mountain—Mount Blum, and Icy Peak—Mount Shuksan.

Except the Skagit River Valley, all major valleys are deep, steep sided, U-shaped troughs that have undergone intense glacial erosion. All are essentially at base level for most of their lengths and have meandering streams and swamps on their flat alluvial floors.

Along most of its course the Skagit River flows through a broad, flat, U-shaped valley. A 25-mile stretch of the river along the east side of the area from the mouth of Big Beaver Creek to the mouth of Diobsud Creek flows through a narrow, steep-walled gorge that shows little effect of glacial erosion. North of Big Beaver Creek the flat, U-shaped glacial trough continues northward into British Columbia, where it crosses a low present-day drainage divide at the head of the tributary Klesilka River and then lies along the valley of Silverhope Creek to the Fraser River at Hope. The gradient is very low throughout this stretch. Downstream from Diobsud Creek the trough has a similar character. In contrast the narrow gorge in the intervening stretch has a steep gradient (nearly 1,000 feet in less than 20 miles) and a sharp V-shaped profile.

We conclude that the divide during the glacial period lay between the mouths of Big Beaver and Diobsud Creeks and that during this period the ice flowed both north and west from this area producing pronounced troughs in each direction.

The last major period of glaciation occurred in late Pleistocene time and eliminated all traces of earlier glaciation. Ice that formed during this glaciation extended well beyond the limits of the study area; thus end moraines related to Pleistocene ice are outside the area. Other smaller moraines, which formed during recurrent minor periods of glacier advance since the last major glaciation, can be found in a number of places. All the larger glaciers remaining in the area are marked by unweathered moraines that lie a few hundred feet to as much as half a mile downvalley from present-day ice margins. Moraines near the head of Luna Creek, which mark the former margin of the composite glacier, are perhaps the best example. Prominent lateral moraines are also present, as along the north side of Challenger Glacier and at the head of the North Fork of the Nooksack River below the East Nooksack Glacier.

Steplike divisions in many of the smaller cirque basins, now bare of ice, are the result of the plucking action of small glaciers after the Pleistocene glaciation.

Those streams which have been eroded to base level and which continue to have a large source of alluvium and glacial debris, such as Ruth Creek and the upper part of the North Fork of the Nooksack River, are braided, and their floors are buried. Where glaciers have been gone for a considerable period, streams have more nearly reached equilibrium, as shown by most of Baker River, Big and Little Beaver Creeks, and the Chilliwack River.

Alpine lakes are scarce and small, despite the intensity of glaciation and the formation of steplike surfaces in many cirques. Apparently, effective headward erosion and relatively rapid movement of large masses of ice led to the formation of long, wide, flat valleys and steep, short headwaters, rather than the formation of local rock basins, as occurred in the less intensely glaciated Pasayten Wilderness area east of Ross Lake. The sparsity of end moraines also accounts for the absence of lakes.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

bul/1359/sec1c.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006